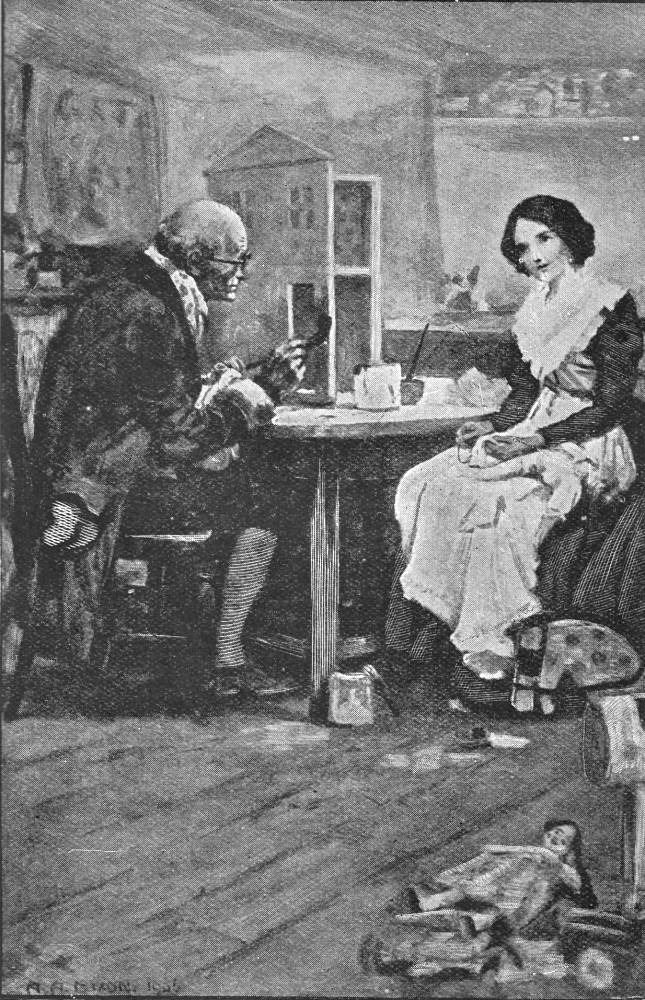

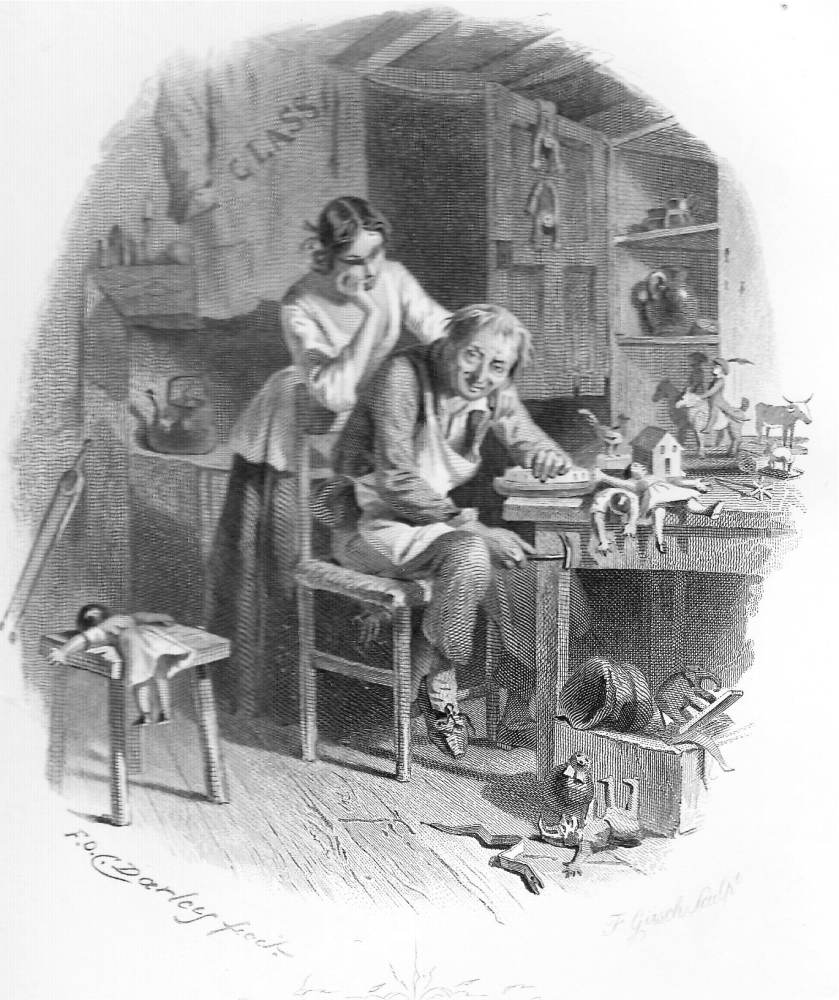

"Caleb and his daughter sat a work."

A. A. Dixon

1906

Lithographic reproduction of watercolour

12.2 cm high x 7.9 cm wide

Fifth illustration for The Christmas Books, Collins' Pocket Edition (1906), facing page 224.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

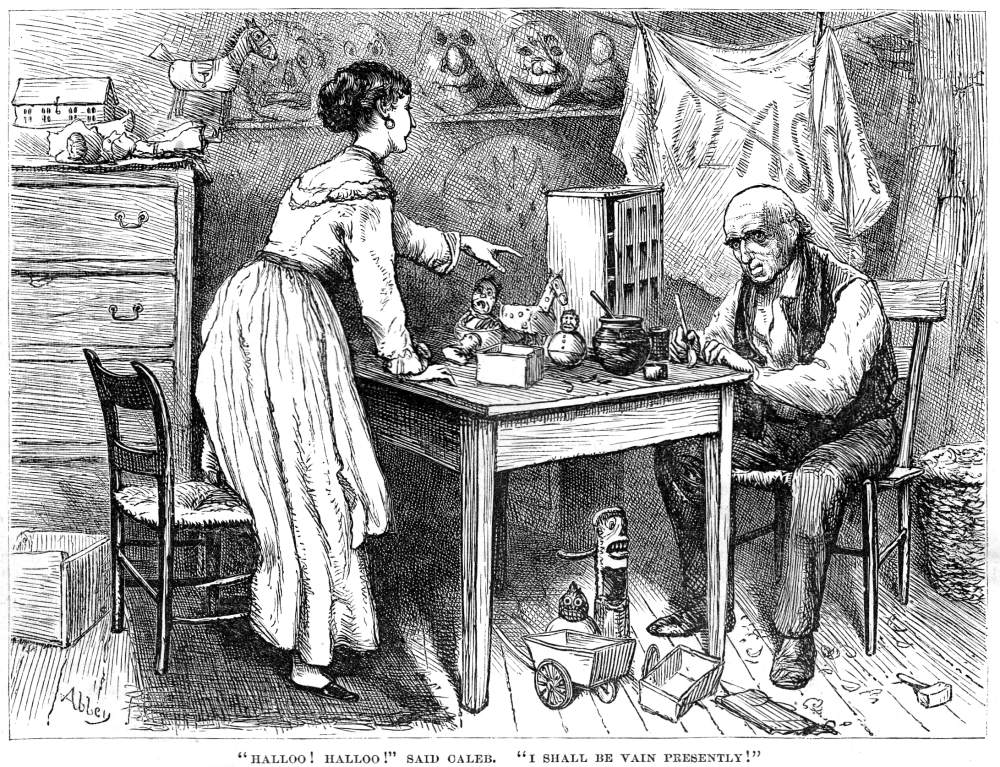

The story's other family is perhaps less typical than the nuclear family of the Peerybingles. I ndigen toy-makers Caleb Plummer, a widower, and his blind daughter combine their domestic and commercial spaces. Although Dixon's illustration does not display their products in the profusion of the accompanying text opposite, he presents Caleb naturally rather than (as in the original) a grotesque, and individualises Bertha. [Commentary continued below.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated from "Chirp the Second"

Caleb and his daughter were at work together in their usual working-room, which served them for their ordinary living-room as well; and a strange place it was. There were houses in it, finished and unfinished, for Dolls of all stations in life. . . . .

There were various other samples of his handicraft, besides Dolls, in Caleb Plummer's room. There were Noah's Arks, in which the Birds and Beasts were an uncommonly tight fit, I assure you; though they could be crammed in, anyhow, at the roof, and rattled and shaken into the smallest compass. By a bold poetical licence, most of these Noah's Arks had knockers on the doors; inconsistent appendages, perhaps, as suggestive of morning callers and a Postman, yet a pleasant finish to the outside of the building. There were scores of melancholy little carts, which, when the wheels went round, performed most doleful music. Many small fiddles, drums, and other instruments of torture; no end of cannon, shields, swords, spears, and guns. There were little tumblers in red breeches, incessantly swarming up high obstacles of red-tape, and coming down, head first, on the other side; and there were innumerable old gentlemen of respectable, not to say venerable, appearance, insanely flying over horizontal pegs, inserted, for the purpose, in their own street doors. There were beasts of all sorts; horses, in particular, of every breed, from the spotted barrel on four pegs, with a small tippet for a mane, to the thoroughbred rocker on his highest mettle. As it would have been hard to count the dozens upon dozens of grotesque figures that were ever ready to commit all sorts of absurdities on the turning of a handle, so it would have been no easy task to mention any human folly, vice, or weakness, that had not its type, immediate or remote, in Caleb Plummer's room. And not in an exaggerated form, for very little handles will move men and women to as strange performances, as any Toy was ever made to undertake.

In the midst of all these objects, Caleb and his daughter sat at work. The Blind Girl busy as a Doll's dressmaker; Caleb painting and glazing the four-pair front of a desirable family mansion.

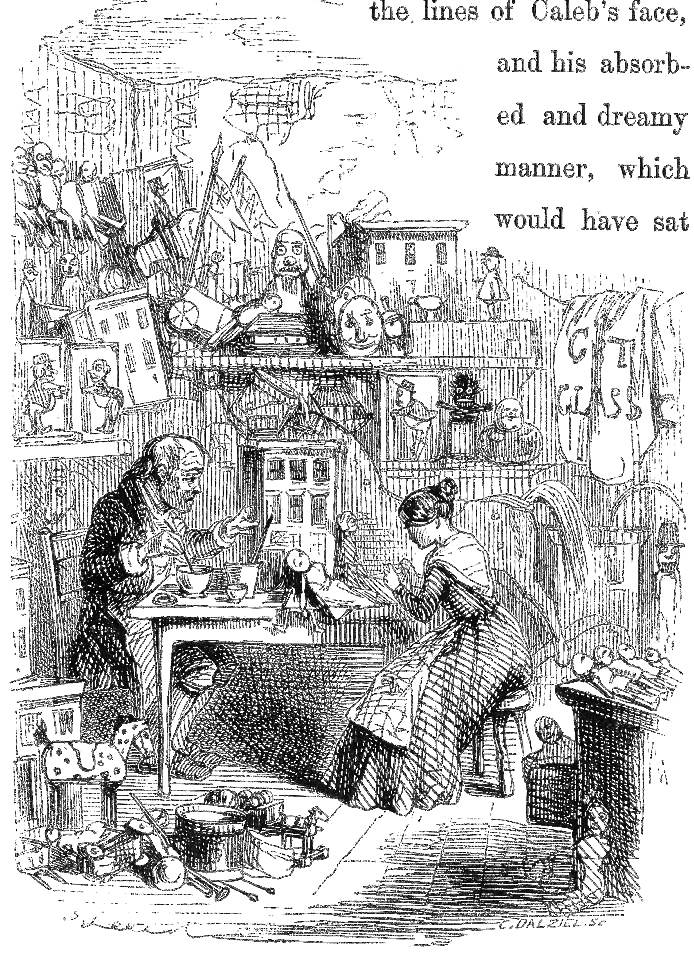

The care imprinted in the lines of Caleb's face, and his absorbed and dreamy manner, which would have sat well on some alchemist or abstruse student, were at first sight an odd contrast to his occupation, and the trivialities about him. ["Chirp the Second," pp. 223-225]

Commentary

Although both John Leech and Fred Barnard have captured the essence of the imaginative Caleb, a shabby, little man who maintains a brave face in order to ensure that grim reality does not oppress his blind daughter, E. A. Abbey in his wood-engraving from thirty years earlier than Dixon's lithograph, "Halloo! Halloo!" said Caleb. "I shall be vain presently!" renders the toymakers' residence-cum-workroom much more effectively, providing numerous toys and dolls, and giving prominence to Caleb's burlap topcoat hanging on the clothesline, with the stencilled "glass" easily read. Although Dixon was not likely to have seen that American Household Edition illustration, he was almost certainly responding to the original volume's and the British Household Edition's images of Caleb Plummer and his blind daughter, who is both May Fielding's friend and the missing sailor's sister. Although her father's deceiving her as to their actual financial circumstances is the parallel of Dot's deceiving her husband about the old stranger's true identity, the next illustrator of the novella, Harry Furniss, does not even include her in his sequence of illustrations.

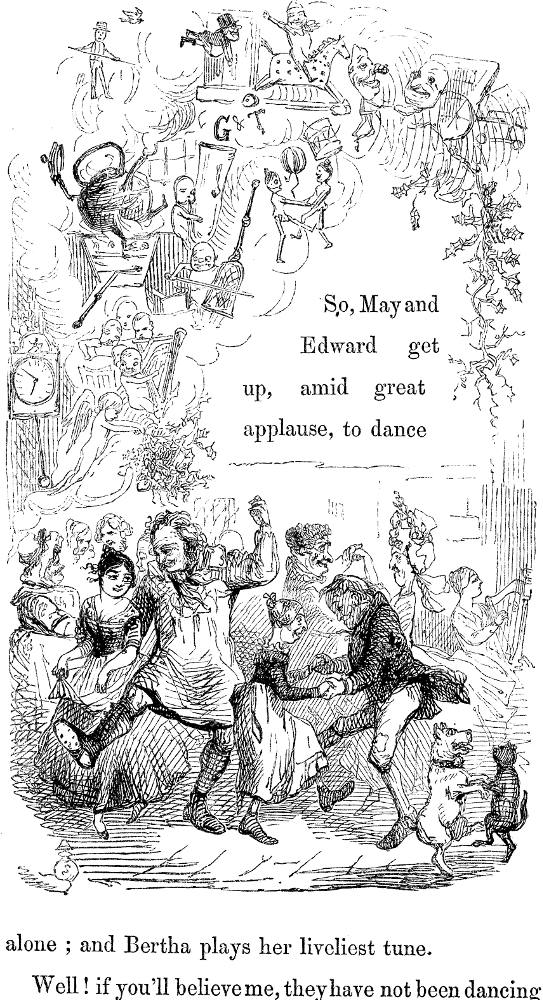

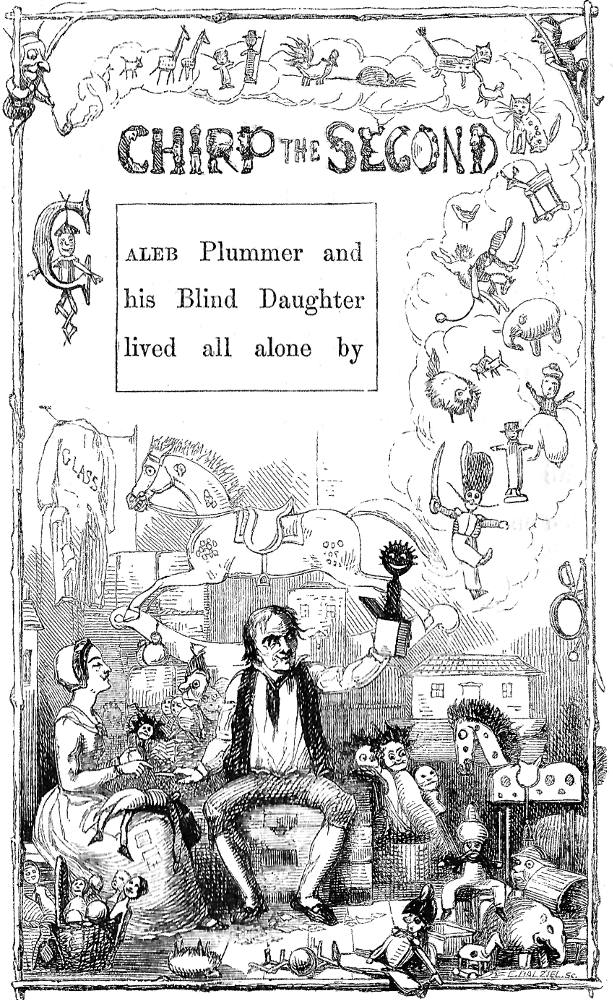

In one of Sol Eytinge's 1867 wood-engravings for the Diamond Edition anthology The ChristmasBooks, American readers received his version of John Leech's 1845 illustration Caleb at Work. In both we have a more convincing toy manufactory than in Dixon's lithograph, but a far less attractive Bertha. In Caleb Plummer and Bertha, Eytinge effectively conveys Bertha's blindness by her sightless but earnest gaze, but her father in that illustration is less realistic, a mere caricature of the Comic Man if contemporary melodrama. Even the original illustrators in their small-scale wood-engravings offer interesting interpretations of these characters, although Richard Doyle's Chirp the Second, despite its interesting synthesis of text and image, and its deployment of fairies amidst the toys, does not develop either the characters of the father and daughter or their relationship. Leech's version, Caleb at Work, again does justice to the toymakers' products, but gives us little sense of Bertha's character, for she is turned away from the reader, and Leech does not attempt to convey her blindness. In his final illustration, The Dance, John Leech pairs up awkward Tilly Slowboy and quirky Caleb Plummer as the story's chief comic characters, but loses their human dimension in his cartoonish exuberance.

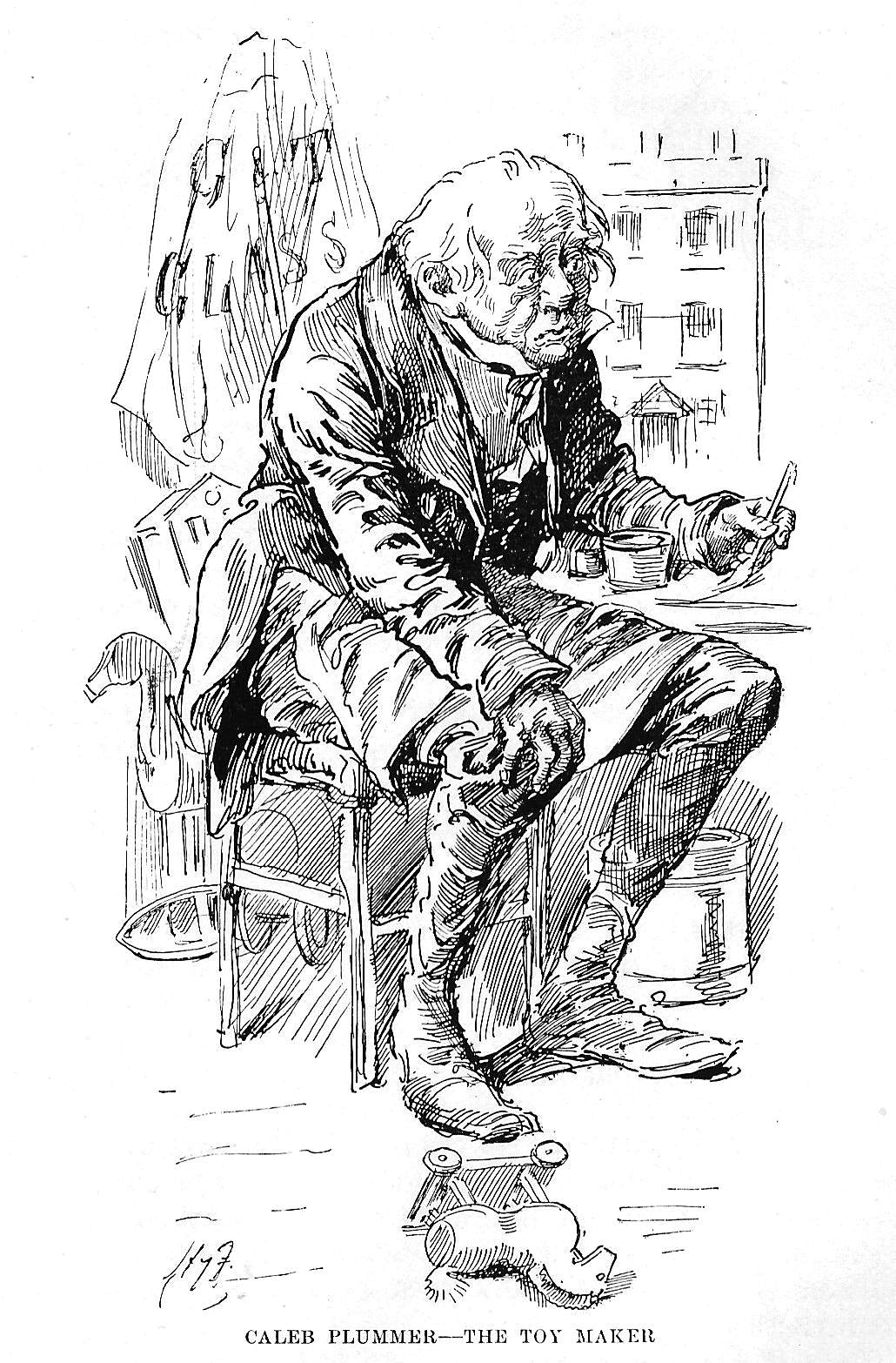

However, in neither these prints dropped into the letterpress nor in the British Household Edition is Caleb so well realised as in Felix Darley's initial frontispiece for the two-volume Christmas Books issued in 1861, with a genial, but also philosophical Caleb looking directly at the reader in "Father," said the Blind Girl, drawing close to his side. . .. The book's next illustrator, Harry Furniss, treats Caleb as a sad, aged, and pathetic clown in Caleb Plummer — the Toymaker, and completely excises the blind daughter from the composition.

Thus, Arthur Dixon strikes the right balance, not merely between rendering the toymakers sympathetically but realistically rather than as caricatures, but also between the backdrop, their working area and living quarters, and the father and daughter in conversation, rendering Caleb an individual rather than a type and Bertha a cheerful, pretty brunette whose gaze suggests subtly that she is attending to the direction from which her father is speaking rather than actually looking at him. Although the area above the balding Caleb is in fact his coat, that this is the garment under discussion is not readily apparent. However, in other respects the detailing is effective as Caleb paints the dolls' house and Bertha works on a doll's dress, like that more famous doll's dressmaker, Jenny Wren, in Our Mutual Friend, best realised in Marcus Stone's October 1865 wood-engraving Miss Wren fixes her Idea. Despite the limitations of the lithograph's orientation, Dixon has rendered the room realistically, with a rocking-horse and doll in the foreground creating depth of field. Although his interpretation is somewhat lacking in humour and properties, it is both convincing and even charming, in large measure thanks to the demure beauty of the blind girl, who is much more an individual than her counterparts in the 1845 illustrations.

Related Illustrations from Other Editions, 1845-1910

Left: John Leech's "The Dance" (1845); centre: Richard Doyle's "Chirp the Second" (1845); right: John Leech's "Caleb at Work" (1845). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Felix O. C. Darley's "Father," said the Blind Girl, drawing close to his side, and stealing one arm round his neck, "tell me something about May. She is very fair?". Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's "Caleb Plummer and Bertha" (1867). Right: E. A. Abbey's "Halloo! Halloo!" said Caleb. "I shall be vain presently!" (1876). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

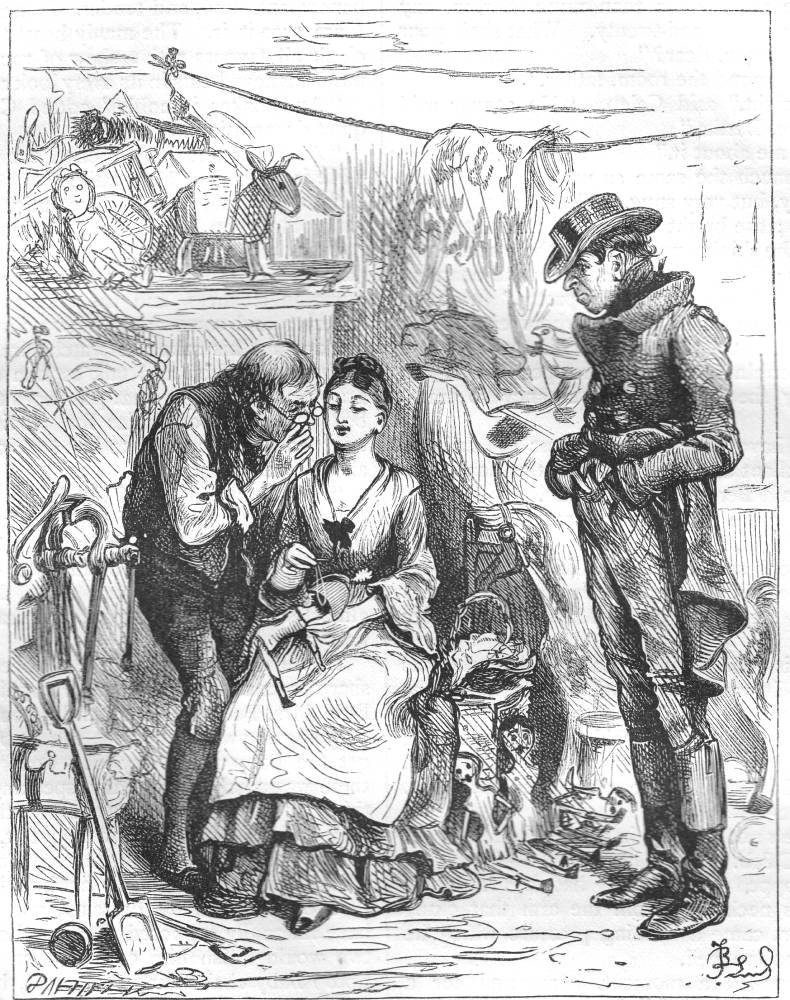

Left: Fred Barnard's "Caleb, Bertha, and Tackleton" (1878). Right: Harry Furniss's "Caleb Plummer — The Toy Maker" (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. The Cricket on the Hearth. A Fairy Tale of Home. Il. John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, Edwin Landseer, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1845 [dated 1846].

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 8.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 8.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1987.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

A. A.

Dixon

Great

Expectations

Next

Last modified 29 March 2014