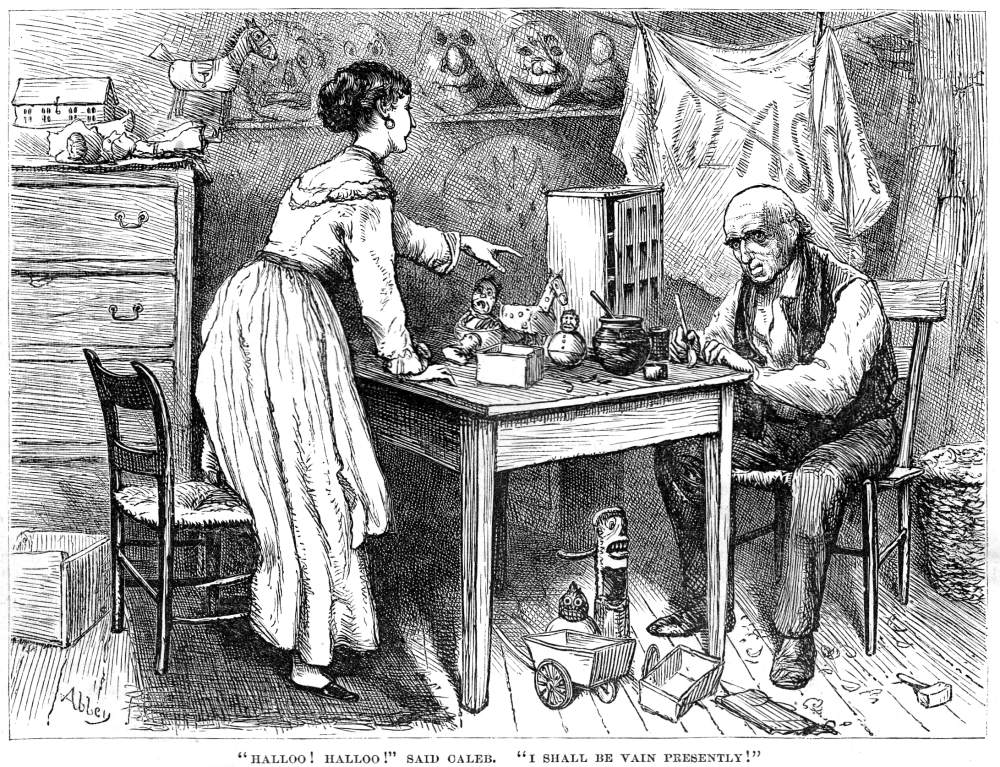

"Halloo! Halloo!" said Caleb. "I shall be vain presently!" by E. A. Abbey. 10 x 13.4 cm framed. From the Household Edition (1876) of Dickens's Christmas Stories, p. 88. Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home was first published for Christmas 1845. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated

"So you were out in the rain last night, father, in your beautiful, new, great-coat," said Caleb's daughter.

"In my beautiful new great-coat," answered Caleb, glancing towards a clothes-line in the room, on which the sackcloth garment previously described, was carefully hung up to dry.

"How glad I am you bought it, father!"

"And of such a tailor, too," said Caleb. "Quite a fashionable tailor. It's too good for me."

The Blind Girl rested from her work, and laughed with delight. "Too good, father! What can be too good for you?"

"I'm half-ashamed to wear it though," said Caleb, watching the effect of what he said, upon her brightening face; "upon my word. When I hear the boys and people say behind me, 'Hal-loo! Here's a swell!' I don't know which way to look. And when the beggar wouldn't go away last night; and, when I said I was a very common man, said 'No, your Honor! Bless your Honor, don't say that!' I was quite ashamed. I really felt as if I hadn't a right to wear it."

Happy Blind Girl! How merry she was, in her exultation!

"I see you, father," she said, clasping her hands, "as plainly, as if I had the eyes I never want when you are with me. A blue coat —"

"Bright-blue," said Caleb.

"Yes, yes! Bright-blue!" exclaimed the girl, turning up her radiant face; "the color I can just remember in the blessed sky! You told me it was blue before! A bright-blue coat —"

"Made loose to the figure," suggested Caleb.

"Yes! loose to the figure!" cried the Blind Girl, laughing heartily; "and in it you, dear father, with your merry eye, your smiling face, your free step, and your dark hair — looking so young and handsome!"

"Halloo! Halloo!" said Caleb. "I shall be vain, presently." ["Chirp the Second," American Household Edition, p. 87]

Clearly throughout this passage that immediately precedes the illustration in the Harper and Brothers' Household Edition, Bertha is seated and stitching the clothing of a doll, rather than standing. Possibly Abbey and Barnard both saw a thematic similarity between Bertha as the grownup daughter with an exceptionality who creates diminutive but perfect beings and Jenny Wren, the sardonic dolls' dress-maker of Our Mutual Friend (1864-65), and that this connection coloured their interpretation of Bertha Plummer as the sightless Angel of the House. The reader of 1876 would, of course, have noted a number of contrasts between the diligent Caleb and the slovenly, dipsomaniacal "Mr. Dolls," and between the patient, cheerful Bertha and the sharp-tongued, self-assertive Jenny, who sees people for what they are rather than what they would wish others would think them.

Clearly throughout this passage that immediately precedes the illustration in the Harper and Brothers' Household Edition, Bertha is seated and stitching the clothing of a doll, rather than standing. In the background, Abbey has strategically placed the burlap sacking with "glass" stencilled in large letters on it to underscore the extent of Caleb's pathetic but comical deception of his blind daughter, for this rough packing material Caleb's artistic imagination has transformed into the beautiful blue topcoat that brings such joy to his blind daughter as she sees it in her mind's eye.

Abbey in attempting to convey the somewhat chaotic nature of the workshop has forgotten one of the cardinal rules for the visually impaired: "Never leave anything on the floor that would trip up the blind person." Barnard, however, has included an equal amount of clutter. The elegant dress, too, that Abbey's Bertha wears is inconsistent with the couple's threadbare poverty. Whereas Barnard has taken pains to fill every available space with toys, Abbey, however, has been careful to include the worktable. But his excluding the domineering figure of Tackleton suggests that Abbey was more interested in investing the scene with domestic pathos rather than exploiting its potential for irony.

Abbey's depiction of the toymaker and his blind daughter compared to those of Doyle, Leech (1845), and Barnard (1878)

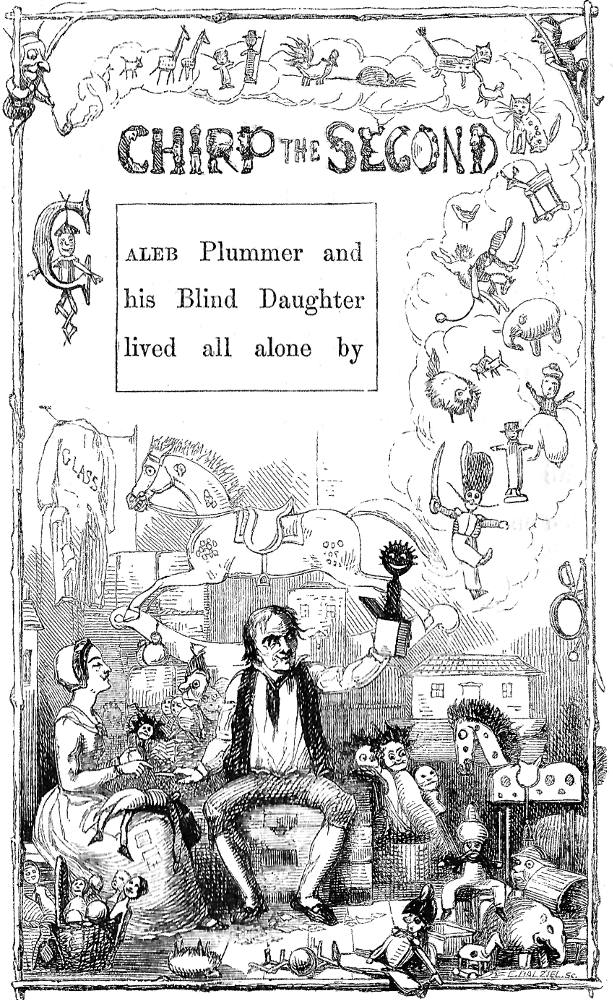

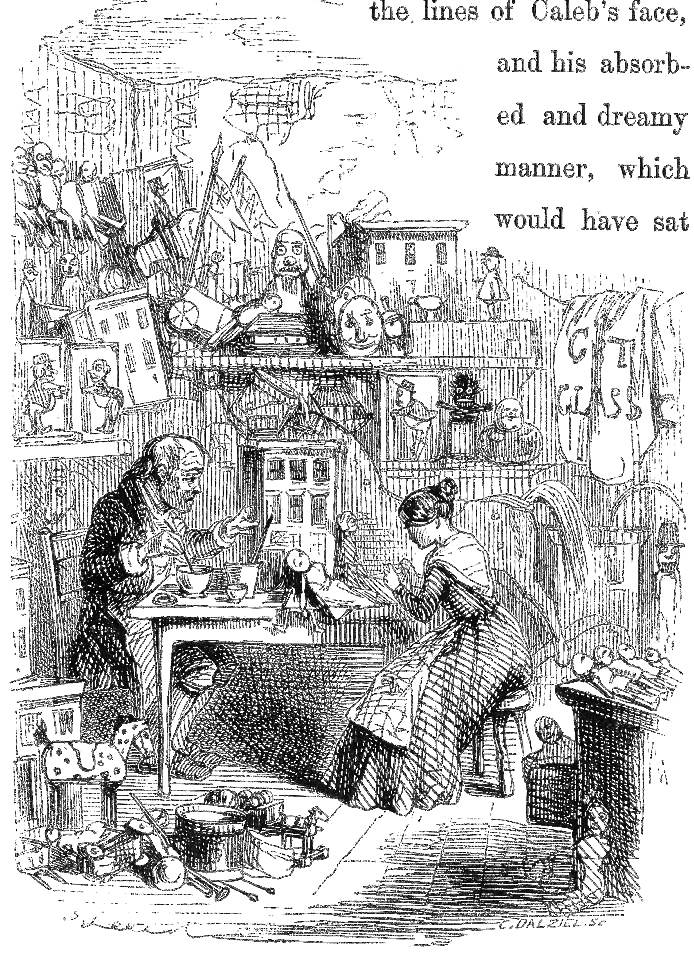

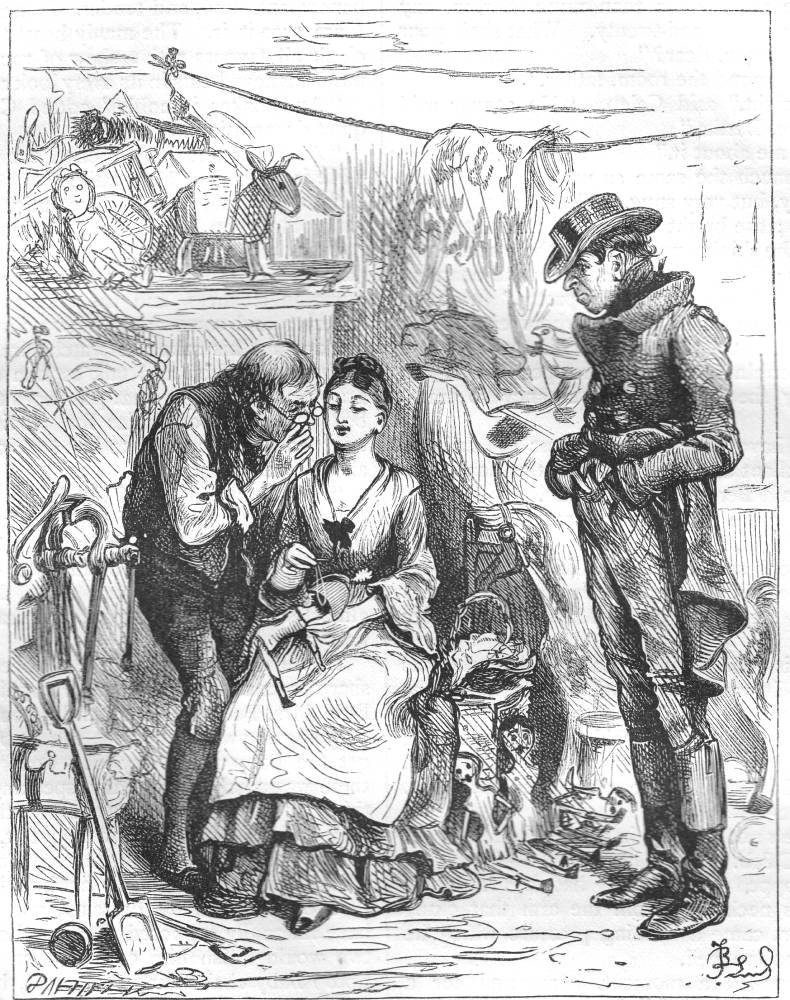

The problem of discontinuity in the handling of their subject by Richard Doyle in "Chirp the Second" (p. 54) and John Leech in "Caleb at Work" (p. 61) cannot have escaped the scrupulous Dickens, but time was brief and the differences in their depiction of these secondary characters were not so great as to disrupt the narrative-pictorial sequence. No such problem occurs in the American and British Household Editions of the 1870s since a separate artist managed each program of illustration. Although Abbey's "'Halloo! Halloo!' said Caleb. 'I shall be vain presently!'" (p. 88) adds little to the earlier volume's descriptions of the Plummers at work in their home ( a very modern situation comparable to today's "home-office," which blurs the distinctions between work and domestic spaces and conflates labour and leisure), Barnard chooses a later moment in the second chapter that presents conflicting versions of the economic plight and standard of living that the toy-making widower and his blind daughter enjoy. Abbey focuses on this nuclear family in a tender moment. On the other hand, Barnard utilises the ironic moment to introduce the misanthropic capitalist Tackleton, a species of Ebenezer Scrooge, albeit somewhat underdeveloped by Dickens as an exploitative employer.

Three illustrations of Caleb and Bertha Plummer in their parlour, which doubles as their workroom: Left: Richard Doyle's "Chirp the Second". Centre: John Leech's "Caleb at Work". Right: Fred Barnard's "'The extent to which he's winking at this moment!' whispered Caleb to his daughter. 'Oh, my gracious!'" (1878).

Although the original illustrators operated under Dickens's supervision, Doyle's and Leech's conceptions of Caleb and Bertha, as well their workroom, differ in a great many particulars. Although both versions have situated the co-workers in the midst of toy production, Doyle emphasises a pair of rocking horses and the myriad of toy-making notions (upper right) that the father and daughter share. Doyle's Caleb works in his shirtsleeves, and his Bertha wears a cap — undoubtedly to keep her hair out of her work. To keep the small-scale illustration uncluttered, Doyle has eliminated the work table, around which Caleb and Bertha are seated in Leech's interpretation of the scene upon which Tackleton will shortly intrude. Both illustrators include Caleb's wonderful great-coat, in fact fashioned out of a sackcloth once used to pack fragile objects and labelled "glass" (upper left in Doyle, upper right in Leech, and right of centre in Barnard). In Leech's, Barnard's, and Abbey's versions of the same scene, the s-called "great-coat" hangs drying on a clothes-line strung across the cluttered workroom, as Dickens's text specifies, while Bertha is busy as "a Doll's dressmaker" (87) — however, in order to make Caleb's and Bertha's heads the picture's focal point, Barnard has dispensed with "the four-pair front of a desirable family mansion" (87, and clearly evident in Leech's and Abbey's woodcuts) which Caleb has been decorating. In Abbey's composition, a respectably clad and fashionably coiffed Bertha points across the worktable at the dolls' "desirable family mansion" (87), which looks rather more like a multi-storied New York tenement building. Her gesture, although not sanctioned by Dickens's text, serves to draw the reader's attention to the burlap sacking hanging on the clothesline. Pointedly Abbey has made his aging Caleb almost entirely bald to foil Bertha's belief that her father still looks young and has "dark hair" (87) The comic part of the accompanying text is that he has obviously described himself to his daughter as "handsome," whereas the illustrator has emphasized Caleb's extreme homeliness.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting, color correction, and linking by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home. Il. John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, Clarkson Stanfield, and Edwin Landseer. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1845.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 15 December 2012