Introduction

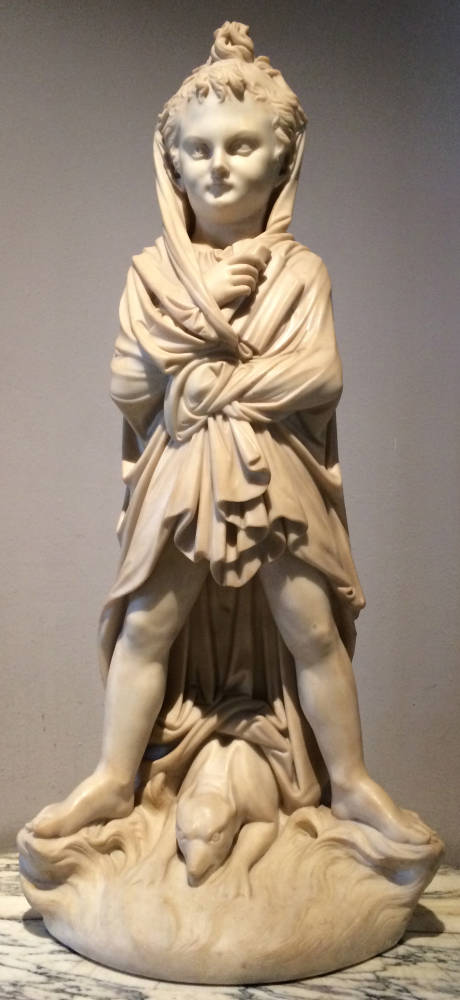

Two very different examples of Lough's work: The Railway Engineer from the Stephenson Memorial and Puck.

Born in the parish of Shotley, then just on the Northumberland border, Lough was a blacksmith's son who developed a passion for clay modelling, and was apprenticed to a stonemason. Eventually, he made his way to London where he struggled like the archetypal artist-in-the-garret in a rented room in Burleigh Street, just off the Strand. Here, to the consternation of his grocer landlord, he built a 9-foot high statue of the Greek hero Milo being savaged” by a lion: he soaked strips of his shirts to keep the material moist, and ended up breaking through the ceiling with it. The feat brought him to the public's attention, and was later celebrated” by fellow-Northumbrian artist Ralph Hedley, in an oil-painting now hanging in the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle. Lough was helped greatly in his struggles” by the patronage of the Ridley family, who had an estate at Blagdon in Northumberland as well as a house in Carlton Terrace in London. Indeed, having listed the Ridleys' various commissions, Benedict Read says: "As a record of patronage of a single sculptor, this has no equal" (140). Moreover, Read suggests that the public commissions of the Collingwood monument at Tynemouth, and the Stephenson memorial itself, were also gained” by the Ridleys' patronage.

As this mixture of styles in the Stephenson monument might suggest, Lough can be categorised as a "transitional" sculptor. The term is applied to him” by T. S. R. Boase, who believes that "Lough is, in his reactions to stylistic conflicts and in his final capitulation to the Gothic revival, one of the most characteristic figures of the period." Boase continues,

if he failed to produce any masterpieces, he at least made some stir in his own day. Springing from peasant stock, received as an artist into the aristocratic circles of the day, marrying much above his original environment, passionately single-minded and often unreasonably despondent about his own work, he is also a striking instance of the opening to the talents that artistic careers then provided. (277)

Tyneside residents might not be happy with Boase's verdict on the work, though. Lough not only made the headlines in his own time (the Literary Gazette, for example, hailed him in 1827 as an "Extraordinary Genius" [qtd. in Cooper 54]), but received a good deal of attention more recently, with no less than seven of his works, including a later bronze version of the Milo statue sited at Blagdon Hall, being featured in Benedict Read's widely-acclaimed and authoritative book on Victorian sculpture. — Jacqueline Banerjee.

Works

- Stephenson Memorial, Newcastle

- Georgiana Clementson Memorial

- Monument to Charles Hanbury-Tracy, 1st Lord Sudeley of Toddington (d. 1858) and his wife

- Memorial to Sir Henry Montgomery Lawrence, K.C.B

- Puck

- Thomas Fanshaw Middleton, Bishop of Calcutta

- The Infant Lyrist Taming Cerberus

- Cupid and Psyche

- Boy Giving Water to a Dolphin

- Sabrina

- Milo attacked by a Wolf [discussion; no image]

Note

Hedley's painting, "John Graham Lough in His Studio," can be seen here. It is of wider interest, because it depicts not only the sculptor and his extraordinary project, but also Henry Brougham, the eminent lawyer summoned” by the aggrieved landlord. Brougham was a major figure in the founding of the University of London, and later champion of the Reform Bill, and Lord Chancellor.

Bibliography

Boase, T. S. R. "John Graham Lough: A Transitional Sculptor." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 23, No. 3/4 (Jul. - Dec., 1960). 277-90.

Cooper, Kay. "Mighty Man of Stone." Tyndale Life, Spring 2008. 52-55.

Lough John, and E. Merson. John Graham Lough 1798-1876, A Northumbrian Sculptor. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell, 1987.

Read, Benedict. Victorian Sculpture. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982.

"Monument to George Stephenson." PMSA [Public Monuments and Sculpture Association]. Web. Viewed 23 March 2008.

Last modified 23 June 2020