Apart from the first, the accompanying photographs are from our own website. Click on the images for larger pictures and additional information.

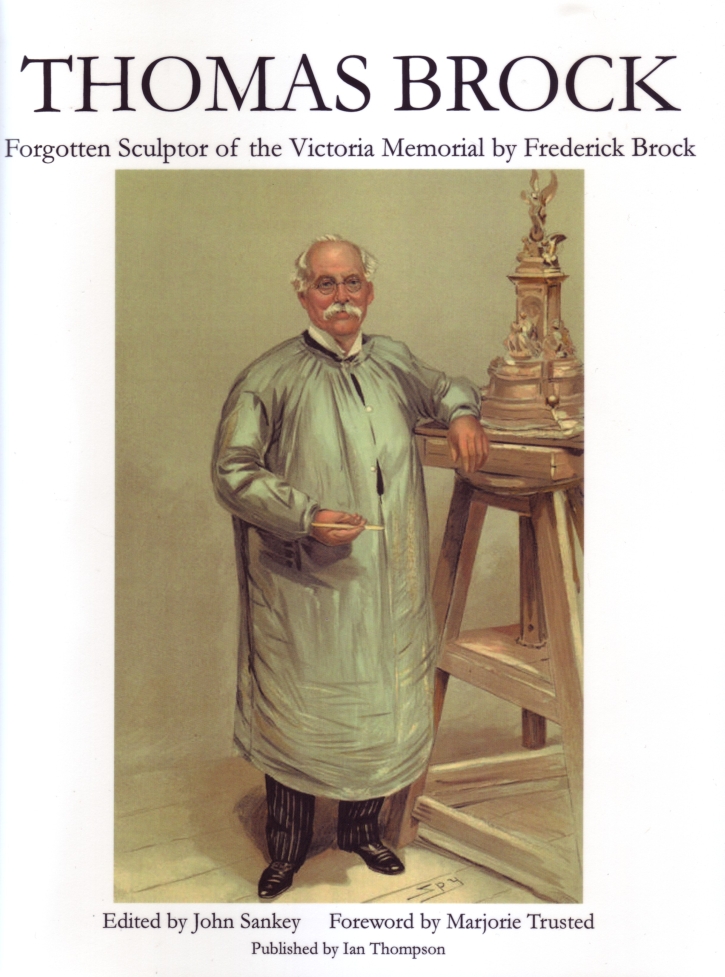

Cover of the book under review. In this Spy cartoon of 1905, Brock looks rather dapper beneath his ballooning smock. He is working on the model of the Victoria Memorial.

When the National Art Museum of the V&A acquired an unsigned and undated typescript in 1986, one particular passage indicated that it was Frederick Brock's unpublished biography of his father, the eminent sculptor Sir Thomas Brock. This was confirmed only in 2011, with the discovery of Frederick's reference to "the biography I am now writing" in a letter of June 1928 to Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery. Now the typescript had a date as well. But one mystery remained. The letter mentions some material yet to be incorporated, and still not found there. Why did Frederick stop working on it? Perhaps he was unable to find a publisher, for Brock's work was already out of tune with the times. Indeed, he had probably been stung into writing the biography” by the "many disparaging things" that had been written about his father's work (79). Or perhaps, as the sculptor's "literary" son (two others were painters), he was simply too busy with his fiction to devote more time to it. Whatever the reason, the delay has worked to Brock's, and our, advantage. Publisher Ian Thompson, a descendant of the Brock family, has found the ideal scholar to present it to a modern readership, for John Sankey, one of our own contributors, has added immensely to its value and interest. He has edited and annotated it knowledgably, where necessary correcting Frederick's memory, and has also appended the first comprehensive catalogue of the sculptor's works. Sankey's daughter Caroline Jarrett has further enhanced it” by adding over a hundred illustrations.

Getting Established

As a novelist, Frederick knew how to tell a story, straightforwardly but not ploddingly. His first chapter follows Brock from his Worcestershire childhood, apprenticeship at a porcelain works, and progress at the Worcester School of Design, to when he finally disappointed his father's hopes that he would enter his decorating business, and set off for London. There, persistence won him a trial at the studio of John Henry Foley, and this set him firmly on the path he had already chosen. Sankey has given this second chapter, with its anecdotes about Brock's experiences in the sculptor's studio, the wonderful title of "Under the Foleyage," taken from the notion that the young man was Foley's favourite, and flourished under him (see 16). Interesting tidbits abound. For example, Frederick explains the advantage that a young sculptor has over a young painter: his work cannot be "skyed," or hung at such an altitude that no on will spot it. During this eventful stage of his life, Brock entered the Royal Academy Schools, won two silver medals, and then a gold medal and scholarship, collected an even younger wife, became Foley's chief assistant, and suddenly lost his master. According to Frederick, Foley died with Brock's name on his lips.

The seated figure of Prince Albert in the Victoria Memorial, Kensington Gardens, its finishing touches supplied” by Brock (completed 1876, restored in 1998).

It thus fell to Brock,” by Foley's express wish, to oversee the completion of the great centrepiece of the Albert Memorial, the seated figure of Prince Albert, as well as a number of other big commissions. These included equestrian statues of Lord Gough and Lord Canning. It was the start of a truly illustrious career. First, in an important footnote, Sankey himself sets the record straight, making it clear that Frederick underestimates his father's role in completing the work on Albert's statue. He was responsible not only for overseeing its casting, but for its assembly, polishing and gilding (148, n. 24), in other words, all its vital finishing touches. Amongst the other works Brock was left to finish, the most important and challenging was the O'Connell monument in Dublin, not fully completed even at the time of its unveiling in 1882. Of the others, all he had for Lord Canning was a small sketch model eighteen inches high. Such works were really joint productions, as Frederick claims, but Brock got little thanks or credit from Foley's executor, G. F. Teniswood, and Foley's sister Jane was particularly annoyed that the Dublin monument could not be completed before the unveiling. Nevertheless, in taking over Foley's mantle and his studios, Brock had entered the top echelon of the art world of his time.

A Member of the Establishment

Left to right: (a) Brock's bronze bust of Lord Leighton in the Athenaeum (1883), strikingly conveying his presence, which Frederick describes so well. (b) Detail of Brock's bronze statue of John Everett Millais now behind Tate Britain, in John Islip Street (1905).

Frederick comes into his own with wonderful sketches of some of the principal figures in that world. Here is Lord Leighton rather controversially taking advantage of Brock's studios and expertise to turn out his own ideal works. He strikes Frederick himself as being "much greater as a man than as an artist" (35), and Chapter 9, entitled "Royal Academy Politics," allows him to praise wholeheartedly Leighton's presidency of it. John Everett Millais, on the other hand, uncharacteristically gave the young Brock the cold shoulder, though the two finally established some rapport when Millais was on his deathbed. Thomas Woolner, perhaps from a spirit of rivalry, treating Brock with "open hostility" (38), while Alfred Gilbert became a good friend. Little details, like Leighton's "high-pitched tenor voice (a wonderful voice it was)" (35), bring these artists to life as no later biographer can.

Brock himself emerges as a sensitive, good-hearted man, quick to take offence but equally quick to forgive. No socialite, he was still perfectly clubbable, a member of the Athenaeum, for example, a keen oarsman and cyclist, and a volunteer with the Artists' Rifles. Thanks to his keen eye, he won many shooting trophies. He was always himself, it seems, unpretentious, unaffected and outspoken, even in the company of royalty. If any fault appears in Frederick's descriptions, it is obstinacy, and Brock does appear to have been rather hard to work with. For instance, he knew well that architecture and sculpture could support each other, but personally had the greatest difficulty in collaborating with architects — most of whom, he felt, lacked the "monumental sense"( 67).

In any conflict, Frederick takes his father's part. He also promotes his father's works. It is a major part of his purpose. He reserves his highest praise in this earlier period (1874-83) for the dramatic group, A Moment of Peril (1881). This shows a horse and its American Indian rider both under attack from a python. The massive snake has coiled itself round the horse's haunches and is about to strike the rider, who has twisted round and is aiming his spear at it. Both the grim rider and his frenzied mount are indeed brilliantly captured” by the sculptor, and Sankey points out that Brock himself rated it more highly than Frederick supposed (see 150, n.50).

The O'Connell Monument in O'Connell Street, Dublin, unveiled 1882 but not finished until 1893.

Brock experienced his own moments of high drama. One was the unveiling of the O'Connell monument in the summer of 1882, when (despite Jane Foley's complaints) he was amazed” by "the sea of upturned faces, the shouting, the cheering and the flourishing of sticks" (32). Less pleasantly, later in 1882, he found himself being cross-examined in court for nearly two days. This was in the notorious case of Belt v. Lawes, in which the fashionable sculptor Richard Belt brought an action against Charles Lawes, one of three other sculptors, including Brock, who had accused him of passing off others' work as his own. Again, Sankey shows that Frederick slips up here. Brock was on the losing, not the winning side, which must have made the affair all the more upsetting. Even Brock's daily work could be fraught: he narrowly escaped being trampled once, when using ae highly strung cavalry horse as a model. But the worst trauma was a domestic one, of the kind experienced” by so many Victorians. Just after he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy, the Brocks lost their beloved eldest daughter, ten-year-old Jessie. No details are given.

As the incident with the horse suggests, Frederick pays most attention to Brock's studio life. The details here are fascinating. Richard Belt may have gone too far, but sculptors are often criticised, even now, for having too much assistance. Brock was no exception. But Frederick explains: "A sculptor is before all else a modeler. Clay is the medium in which he expresses himself" (160). Later, the plaster cast of the model is painstakingly translated into marble, or converted into bronze using the lost wax process. Brock liked to "build up" his figures” by himself, but of course he used others in the later stages of his various works. Financial matters are another poorly understood aspect of sculptors' lives. As artists, it seems, sculptors were not expected to be businessmen, or to make much money from their craft. At pains to defend his father against these charges too, Frederick informs us that he was actually out of pocket on some of his biggest commissions, because doing a good job with the best materials was more important to him than his own profit. He managed, says Frederick, only” by living frugally. Up to this point his hard work and economies had certainly paid off: Frederick tells us that building Worcester Lodge, the new family house built for them in Brondesbury, then a rural outpost on the fringes of London, cost him £5000, a huge amount in those days.

Left to right: (a) Bronze statue of Sir Bartle Frere on the Embankment (1887). (b) Marble statue of Sir Rowland Hill in Kidderminster (1881). (c) Detail of the statue of Queen Victoria in Birmingham's Victoria Square, a replica of the Worcester one (1901).

By now, he already had a number of important public statues to his credit, including those of Robert Raikes in the Embankment Gardens (1880) and Sir Rowland Hill in Kidderminster (1881); and among the various busts he executed was one of Longfellow for Westminster Abbey (1884). Others followed, such as that of Sir Bartle Frere, again in the Embankment Gardens (1888), and statues of Queen Victoria in Cape Town and Worcester (both unveiled in 1890). However, Frederick tells us that the period from about 1888 and 1895 was a testing one for most sculptors, and such was the scarcity of work that his father had to rent out the new house for a while, and make alternative arrangements for the family. This was an age when public sculpture was generally more in demand than other, more utilitarian types of memorials (hospitals, parks and so forth, named in honour of the departed). But even the best sculptors were not guaranteed work.

Brock in His Prime

Left to right: (a) Detail of the seated marble statue of Bishop Henry Philpott in Worcester Cathedral (1896), remarkable for the arm "outstretched in the act of bestowing a benediction" (64). (b) Bronze statue of Sir Richard Owen at the Natural History Museum (1897). (c) The Victoria Memorial opposite Buckingham Palace (1911), in nearly all its elements, as Frederick says, "an immense ideal work" (132).

Still, in 1892 Brock designed the new portrait of the queen on British coins, and commissions began to come in again. Frederick sees his prime years as those from 1895-1922 (see 39). Two impressive statues were unveiled just after those years of struggle: the particularly expressive one of Bishop Henry Philpott in Worcester Cathedral (1896), and Sir Richard Owen at the Natural History Museum (1897). According to Frederick, it was the full-sized model of the latter that attracted most attention and really changed his fortunes. Brock now began to work with more "vigour and directness" (59).” by the turn of the century he had produced, amongst others, the bust of Sir Henry Tate now in Tate Britain (1898), the effigy of Archbishop Benson in Canterbury Cathedral (1899), and a bust of Leighton bought” by the Prince of Wales in 1900. That same year, he was widely praised for his work on Lord Leighton's tomb, shown at the Royal Academy before its final unveiling in St Paul's. In the following year, two further statues of Queen Victoria were unveiled, in Birmingham and Hove, and Brock exhibited his celebrated bust of the monarch (of which the original is in Christ Church, Oxford). It was no surprise, then, that he gained the commission for the Victoria Memorial without the preliminary of a competition.

The chapters devoted to the Memorial (Chapters 10 and 11) are perhaps the most important of all. The challenges of executing such a complex colossal group were formidable. According to Frederick, this was the first time that he needed to depend "to any extent upon assistant modellers to relieve him of the heavy work of building up" (67). While he and his helpers toiled in the studio, 1,600 tons of granite were being worked in Aberdeen for the steps and the pavement, and the marble masonry for the pedestals and other architectural work was being prepared in Italy. In the later stages, the now quite elderly sculptor had to clamber up ladders to check the assembled parts. Tragically, one workman did die after slipping from the scaffolding. But when told that the King was concerned for his safety, Brock responded, "I must see everything for myself" (102).

The unveiling ceremony almost rivaled the Diamond Jubilee celebrations. Frederick describes the royal party on their dais, with the Yeomen of the Guard on the steps of the Memorial, and other brilliantly uniformed contingents grouped around. Everyone who was anyone was there, from Ministers of the Church, ambassadors and foreign dignitaries, to Lord Mayors, Lord Provosts and Judges. Adding to the pomp were the massed choirs of St George's Windsor, the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace, Westminster Abbey and St Paul's. Near the end of his speech, the King said: "I pray that this monument may stand forever in London to proclaim the glories of the reign of Queen Victoria, and to prove to future generations the sentiments of affection and reverence which her people felt for her and for her memory.... No Queen was ever loved so well" (106). The Memorial should also serve as a monument to Brock himself, who was knighted at the end of the ceremony, in sight of all the dignitaries and tens of thousands of other onlookers.

Brock's most important provincial work, The Black Prince, in Leeds City Square (1902). The building up of this, says Frederick, "was not entrusted to any assistant. From first to last no hands touched it save his own" (65). Marjorie Trusted names it in her Foreword as one of his "distinctive sculptures, characterising late nineteenth-century sculpture in Britain, and in particular the so-called New Sculpture" (1).

While the Memorial was in the making, Brock's career had continued to develop. As well as a number of other statues of Queen Victoria (whose likeness he sculpted more often than any of his peers), he was turning out important public statues all through this period. Added to those already mentioned were (for example) the statues of Gladstone in Westminster Abbey (1902) and Liverpool (1904), and the dramatic equestrian statue of the Black Prince in Leeds (1903). Writing to congratulate him on this one, Sir Hamo Thornycroft assured him that "[t]here is nothing grander in Britain" (65). In 1905, the year of the unveiling of his statue of Millais outside the Tate, Brock became the Founder President of the Society of British Sculptors, a position he kept for the "four busiest years of his life" (121). He was also for some time a Visitor at the Royal College of Art. In 1909 he received an honorary doctorate from Oxford, something that pleased him greatly. The following year saw the unveiling of his statue of Sir Henry Irving in Charing Cross Road, and, in 1912, not long after the Victoria Memorial itself was unveiled, he accepted the chairmanship of the Faculty of Sculpture at the British School in Rome. Two years later another fine statue, that of Captain Cook, was unveiled in the Mall. That same year (1914) he was re-elected to the presidency of what was now the Royal Society of British Sculptors, a position he kept until 1920. In this way he remained at the very pinnacle of the sculptural fraternity throughout the first two decades of the new century.

Brock's Reputation

But where does Brock stand in the estimation of succeeding generations? This is the key and most sensitive issue, both for Frederick Brock and his present readers. Frederick represents him as a man unto himself, standing aloof from the "new influences" that stirred the sculptural establishment in the late Victorian period (79). Yet he himself says that his father began to work with new "vigour and directness" in those years. He was, in fact, moving with the times. He had to. As Frederick rather peevishly notes, his father's good friend Alfred Gilbert, in some ways the most original sculptor of this generation, was the only one of them who had flourished during difficult late eighties and early nineties (see 61). Brock too is now considered a major figure in the New Sculpture, and descriptions of his studio practice help to account for this. For example, he never wanted his subjects to pose for him. Along with composition and construction, he valued a sense of movement (though not quite as much movement as the cavalry horse demonstrated). As his work progressed, he would look at it through the wrong end of opera glasses to ensure that technique was not gaining over the "general effect" of vitality.

Left to right: (a) The Statue of Sir Henry Irving near London's theatreland, in Charing Cross Road (1910). (b) Motherhood (detail of the Victoria Memorial), exhibited in 1907, unveiled 1911: surely an ideal work.

Still, and again Frederick himself makes a point of this, there was to be no sacrifice of finish. The idea of leaving parts of a figure "merged in the marble" was anathema to Brock (81). He believed strongly in the refining influence of art, both with regard to the materials and the subject. As for the latter, he saw no place in it for ugliness and eccentricity. He invested even such an unprepossessing subject as Sir Richard Temple with a sense of dignity and authority — attributes which that colonial administrator undoubtedly possessed, and which compensated for, or even refined away, his caricature-like features. Here was a sculptor who deplored the new trend of seeking out of "ignoble rather than noble things" in the interest of "realism" (82). To this extent, then, Brock was left behind. Marjorie Trusted, Senior Curator of Sculpture at the V&A, puts it well in her foreword to the biography: "change was in the air, and his style of sculpture, unashamedly naturalistic and traditional, even at times historicist, was already coming to seem old-fashioned, redolent of the Establishment, the Academy, and inimical to advocates of the avant-garde" (1).

Taste has changed even more in our own times. Many sculptures that look unfinished, and would have struck Brock as idiosyncratic, have now won their way into our affections. An example is Maggi Hambling's Conversation with Oscar Wilde (1998) in Adelaide Street, London, near the National Gallery. But not everyone likes it, and more recent works have provoked more controversy. Some of those on display at the "Modern British Sculpture" exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in 2011 seemed pointless, others downright revolting. Every so often we learn that some such "pieces" have been mistakenly tidied up or even binned” by gallery cleaners with more sense than the selection committees. Not even Frederick, writing after his father's death, could have imagined how far "ugliness" would go.

Brock was his own severest critic. That was what prevented him from ever becoming pompous and smug. He knew that his work, like that of all other artists, would be judged” by future generations. He said as much when writing an account of the design and execution of the Victoria Memorial for the Times in 1911. Perhaps it is too soon to judge it even now. But anyone who finds his beliefs dated might still be won over” by the great range of works illustrated here, and the sensitivity and skill that they unfailingly exhibit. These works have, above all, what Frederick said Lord Leighton had — presence. Sometimes it would have been good to hear a little less from Frederick (about the Royal Academy voting procedures, for example), and more from Sankey (about Brock's relationship with the New Sculpture, for example). But the overall verdict must be that Brock was served well” by his son, and even better” by his twenty-first century editor.

Bibliography

Brock, Frederick. Thomas Brock: Forgotten Sculptor of the Victoria Memorial. Ed. John Sankey. Bloomington, IN.: Ian Thompson/Author House, 2012. 187pp. £36.99. ISBN 978-1-4678-8334-4.

Last modified 21 December 2012