In late March 1846, at a small party at Denmark Hill, guests listed in John James's diary were Lady Colquhoun and [Robert?] Monro (both close friends of John James), and "Gordon & Brother" (JJR Diary). Gordon had two brothers, Alexander and William.

Modern Painters II was published on 24 April 1846, and received generally favourable reviews. Perhaps apprehensive about public reactions to the work, Ruskin and his parents left England before its publication, and did not return until late September. This was yet another long continental tour. Ruskin was now turning his attention to architecture, to the churches and cathedrals of France and Italy.

Gordon’s academic career progressed. In 1846 he was appointed University Reader in Greek, and Proctor in the University and Censor of Christ Church in succession to the Rev. Henry George Liddell who left Oxford to become Headmaster of Westminster School. The following year the degree of Bachelor in Divinity was conferred upon him.

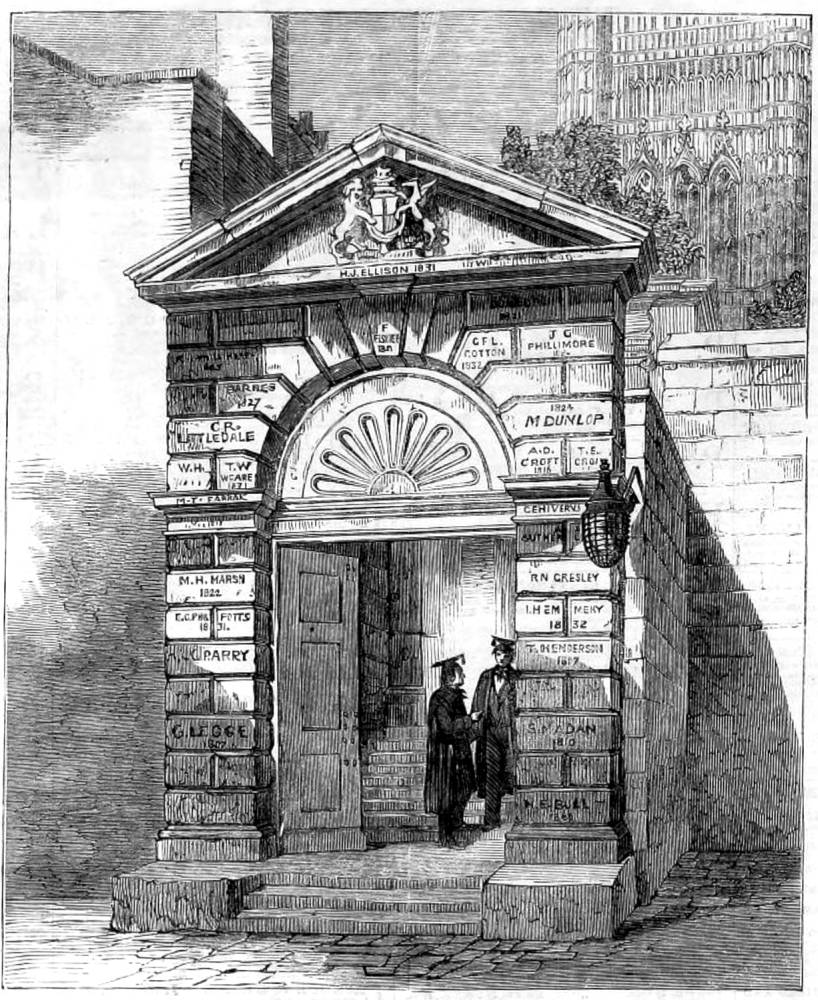

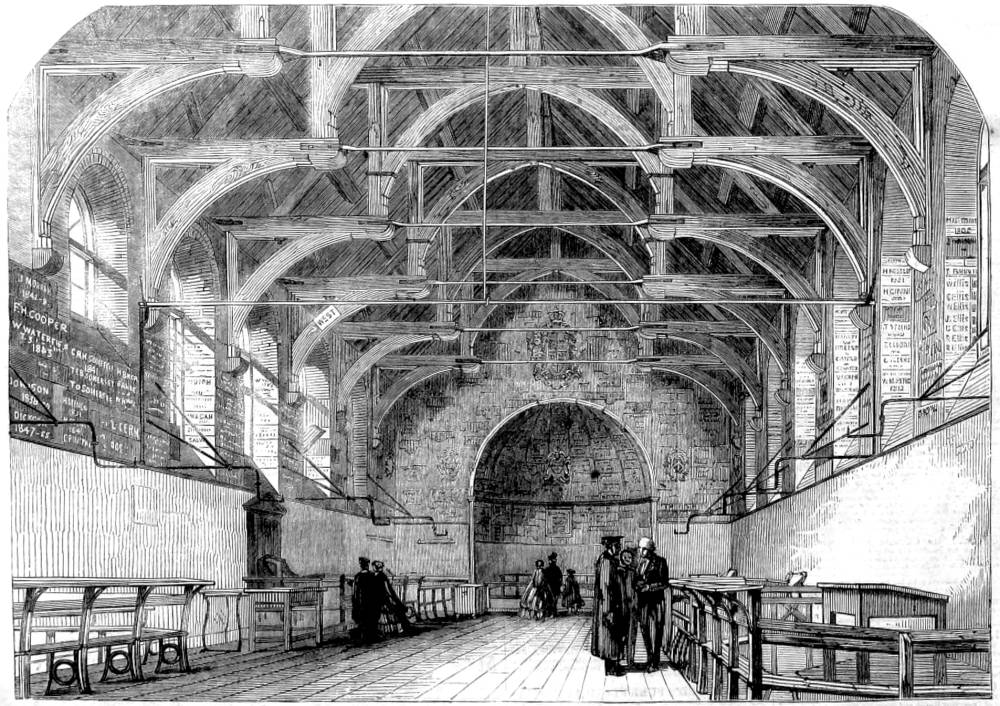

Left: Entrance Gateway of Westminster School. Right: Westminster School. Illustrated London News (24 November 1860): 502.

But the year ended with personal sadness. Gordon’s mother, Elizabeth, died at Linley Hall, during the Christmas vacation, on 27 December 1846. She was aged 64. Her burial took on New Year’s Day, 1847, at Broseley: the ceremony was performed by the Rev. Orlando Forester (SA, Shrewsbury, Register of Burials in the Parish of Broseley.). Her spinster sister, Martha Onions, took over many of her responsibilities: she is listed as the head of the household at Linley Hall in the census of 30 March 1851.

When the headship of King Edward VI School, Birmingham, became vacant in 1847, Gordon, then aged thirty-four, applied for the post. It would have meant severing his links with Christ Church and he was uncertain about his decision. His weekend stay at the Ruskin family home, from Saturday until Monday 22-24 January, provided him with a much-needed opportunity to discuss the consequences of his action (JJR Diary). Gordon may have been invited with this express purpose in mind: John James and Margaret Ruskin would have been ready to give advice. He shared his concerns with Ruskin, who then informed his fiancée Effie Gray that Gordon was "anxious about this Birmingham affair" (Lutyens, The Ruskins and the Grays 81. Hereafter cited as Lutyens2). Gordon was unsuccessful in spite of at least twenty-eight testimonials by Oxonions (including John Ruskin) in support of his application (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. c. 7054, fols. 1-94.). He was rejected on the grounds of his lack of experience of leading a school, as Mrs Ruskin explained to her husband in a letter of 3 February 1848: "Gordon does not go to Birmingham, they want one who has kept school before" (Lutyens2 82n). But such a post of responsibility would nevertheless have suited Gordon and given him the chance to shape young people's lives.

Gordon took a keen interest in education at all levels. Before the Long Vacation in 1847 he published a pamphlet entitled "Considerations on the Improvement of the Present Examination Statute and the Admission of Poor Scholars to the University". One of his suggestions was that a "much freer play would be given to the genius of individual minds, and to talent of all sorts, within the system [Gordon’s emphasis], both in respect of matter and of time". In this plea for respect for the individual, Gordon was thinking not only of himself but more likely his student, John Ruskin. As one who had received a scholarship, he was aware of the large numbers of poorer scholars whose parents could not afford an Oxbridge education for their sons. So Gordon proposed a scheme for existing Oxford Colleges to take "300 poor scholars" to reside in "an affiliated Hall to be governed by a Resident Fellow". He also proposed links with National Schools and Grammar Schools to Oxford. At the back of his mind was the Careswell Scholarship at Bridgnorth School that fed into Christ Church. He believed and argued that such a system would revitalise Oxford and give the Church more power over more people and would consequently flourish as a tree "that is planted by the river’s side".

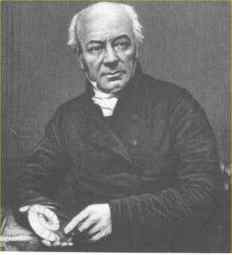

William Buckland. Dr. Buckland is remembered as the man who, in 1824, identified the megalosaur on the basis of a jawbone and other fossil remains found in Stonesfield, near Oxford.

But that January weekend at Denmark Hill was not entirely laden with anxiety about the Birmingham post. Gordon delighted in entertaining Ruskin with "nice stories" and gossip about Oxford, much of which was relayed to Effie. One such story was about Dr William Buckland (1784-1856), Professor of Geology at Oxford, and since 1845 also Dean of Westminster. Buckland was considered to be an extreme eccentric. The state of his house, more like an untidy and dusty museum of natural history, led John Ruskin in his early days at Christ Church to describe the scene in a letter to his father: "not a chair fit to sit down upon – all covered with dust – broken alabaster candlesticks – withered flower leaves – frogs cut out of serpentine – broken models of fallen temples, torn papers – old manuscripts – stuffed reptiles ... stuffed hyena's [sic), crocodiles and cats" (quoted Batchelor 38).

Things did not seem to have changed much in 1848, when the state of his house was still a subject of discussion, curiosity and amazement. Ruskin wrote to Effie, relaying the gossip and the flavour of Gordon's humour: “The Dean of Westminster's house came under discussion – dirty – or not dirty? I said it was not strictly speaking dirty – but only mellowed and toned. Well – said Gordon – ‘there was a Rats nest behind the sideboard in the dining-room that filled a barrow!’” [Lutyens2 82]

Another of Gordon's stories was about rowdy students:

One of the Tutors had been disturbed by a party making a noise over his head at 12 o'clock. He went up to them – they were rather rude, and he brought them up before the Dean the following morning, who asked "how they came to be making a noise, – "Why – Sir," said one of them – "we couldn't be making much of a noise – for there were but twelve of us, and we were only singing!" [Lutyens2 92]

In a letter to Effie who was preoccupied with wedding preparations, Ruskin quotes one of Gordon's sayings indirectly (through his mother) and directly: "My mother […] says not to mind what you finish or what you don't. Pray recollect Gordon's – 'It doesn't matter how much you have to do if you don't do it'" [Lutyens2 82] This is an echo of Gordon's earlier advice to young Ruskin: "When you have got too much to do, don't do it."

Ruskin's self-portrait and two of Millais's drawings of Effie. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The marriage ceremony took place on 10 April 1848, in the drawing-room of the family home Bowerswell House, Perth, in Scotland. Ruskin’s parents did not wish to attend for Bowerswell was associated with too many unhappy memories. The house had originally belonged to Ruskin's ill-fated and debt-ridden grandfather, John Thomas, who had committed suicide there in 1817 by slitting his throat. Margaret Cox's marriage to John James Ruskin was postponed for many years during which time her fiancé worked hard to pay off his father's debts. None of Ruskin’s friends attended the wedding, either. Seven years later, Effie and Millais would be married in that same house.

Euphemia Chalmers Gray, usually called Effie, was a pretty, vivacious, nineteen-year-old when she married John Ruskin, aged twenty-nine. She loved parties, fashionable clothes and socialising, in stark contrast to the rather dour man to whom she had pledged lifelong fidelity and who preferred stones to sex. F. J. Furnivall, a Christian Socialist lawyer and vegetarian who was a devotee of Ruskin, described Effie at a party soon after her marriage as a "handsome, tall woman, with a high colour, brown wavy hair, a Scotch woman evidently, dressed in a pink moiré dress" (Lutyens1 23). The couple were ill suited and incompatible: the marriage was doomed from the start. After a short honeymoon in the Highlands and Keswick, the couple returned to Ruskin's parental home at Denmark Hill and the constant vigilance and increasing control of the older Ruskins.

Owing to political turmoil and revolutions in continental Europe, Ruskin changed his travel plans from honeymooning abroad and remained in England for several months until calm was restored. After spending two weeks in Dover, and prior to joining Ruskin’s parents for a proposed tour of English cathedrals, John and Effie were invited to stay for two weeks in early July with the Aclands at their house in Broad Street, Oxford. It was the time of Commemoration, the great festival of the Oxford academic year. Effie enjoyed immensely the "continual round of festivities", the endless parties and social whirl. She made the acquaintance of Gordon whom she quoted as saying that this was a time when "every two people meeting on the street exchange invitations" (James 115). She described the ceremony, that took place on 3 July in the packed theatre, with much verve in a letter to her parents:

We went in at ten o'clock, the Ladies being all separated from the gentlemen had a very gay appearance, and the place was crammed full. Then above was the undergraduates gallery and, after the rest of the Theatre was full, all the young men, the doors being opened, rushed in and filled the place just like savages. Then they called out names and shouted or hissed as the person was popular or not, first the Queen and Royal family, then Guizot – tremendous cheering, then Dr. Pusey followed by Jenny Lind, then the Ladies in white gowns, ditto in Pink bonnets and ditto in black which met with no approval, then "the men that got the Prizes'' followed by the "men that didn't get them", then Mr. Gladstone, who had come to have his degree, was cheered and hissed for seven minutes till both parties were quite exhausted. The Organ then played God save the Queen when every person joined which was very impressive. Then the Chancellor Dr. Plumtree conferred the degrees on Baron Hugel, Mr. Gladstone, Mr. Hallam, Mr. Cotton etc. [James 115-16]

Within a very short time Effie made the acquaintance of many titled people: Mr and Lady Anna Gore Langton, Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, Lady Morgan, Lady Brougham, Lady Dunmore, Lady Dufferin and Lady Lansdowne to name but a few. She was "overwhelmed with invitations" (James 115), and impressed by this kind of society. Naturally she also met and charmed many academics, friends and colleagues of her husband.

On the morning of 4 July, Effie and John were invited by the Rev. E. Hill, Ruskin's former Mathematics tutor, to breakfast in Christ Church Hall. "About 30 sat down" Effie wrote to her parents, "and enjoyed a very nice meal with fine fruit afterwards" (James 116). Gordon, a close friend of Mr Hill, may also have been present on that occasion. Feiling, in his book In Christ Church Hall, mentions an invitation by Gordon to the young couple to have breakfast in the Hall during this period. That marked what Feiling regarded as the beginning of Ruskin’s via dolorosa (Feiling 185). Differences were quickly emerging between the couple: during a performance of Haydn's Creation, which Effie "enjoyed very much", John found the "music detestable and […] read a book the whole time" (James 115).

Salisbury Cathedral, its Cloister, and Nave. Photographs courtesy of George P. Landow.

Ruskin's mind was on architecture and a book on that subject. On leaving Oxford, his planned "pilgrimage to the English Shrines" (8.6) had to be aborted (apart from a miserable visit to Salisbury Cathedral) due to illness – Ruskin and his mother caught a heavy cold, his father fell ill with a stomach complaint. So the English tour was replaced by an architectural study tour of Northern France, mainly Picardy and Normandy. It lasted almost three months, from 7 August until 25 October. Ruskin and his wife, assisted by Hobbs, their devoted amanuensis and factotum, and accompanied at the beginning by John James Ruskin, set off for Abbeville via Boulogne from where John James returned to England. It is unclear whether he intended accompanying his son and daughter-in-law further. We can only speculate as to his motives in going as far as Boulogne.

Two of Ruskin’s watercolours from later trips to France: Left: Entrance to the South Transept, Rouen Cathedral. Source: 35.371. Right: View from the Base of the Brezon above Bonneville . 862-63. Graphite, ink, watercolour, and bodycolour wash on white paper, 35.2 x 51.3 cm. Collection: Lancaster (1206).

Ruskin had planned the route exclusively according to his own wishes, needs and aims. The purpose of the tour was work, non-stop work at his usual pace, from very early in the morning until late at night, studying, sketching and measuring cathedrals and churches. Ruskin was preparing his first illustrated book The Seven Lamps of Architecture (complete text). This was the first real experience that Effie had of her husband's capacity for work and the gruelling schedule that he imposed on all around. It was in stark contrast to the social whirl of Commemoration in Oxford. They travelled hundreds of miles over rough terrain, often by stage-coach, and occasionally by train. From Abbeville, they went to Normandy, stopping wherever there was an important religious building, such as in Rouen, Lisieux, Falaise, Vire, Mortain, Coutances, Saint-Lô, Bayeux and Caen.

Retracing Ruskin’s steps. Left: Coutances Cathedral. Middle: St.-Lô, église Notre-Dame. Right: Bayeux Cathedral. Photographs courtesy of George P. Landow.

Effie's husband was preoccupied with his work, and angry at seeing so many buildings destroyed, often razed to the ground, in the name of restoration. "John is perfectly frantic with the spirit of restoration here", Effie wrote to her parents, "the men actually before our eyes knocking down the time worn black with age pinnacles and sticking up in their place new stone ones to be carved at some future time" (Links 26). So great and uncontrollable was Ruskin's temper that only Effie's "gentle mediation" prevented him from "knocking some of the workmen off the scaffolding" and probably being put in prison (Links 26-27). Clearly, Effie was unsuited to this lifestyle and however hard she tried, could not adapt. She was not accustomed to long walks and after half a mile, Ruskin reported to his mother, "is reduced nearly to fainting and comes in with her eyes full of tears" (Links 27). Ruskin was insensitive to her needs and incapable of displaying sympathy. Ruskin maintained his usual high level of correspondence, his almost daily letters to his parents and friends. Among these was Gordon to whom he wrote from Bayeux (Lutyens2 157).

It must have been a great relief to both to return to London, for Ruskin to use his copious notes to write The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and for Effie to enjoy being a hostess at 31 Park Street, Grosvenor Square. But the fashionable house was not really theirs: it had been acquired for them on a three-year lease by John James Ruskin. There seems to have been no consultation about the house and it may well have been a cunning ruse by John James to appropriate his son. John James would have known that his son would not like it. For although the choice of location was ideal for Effie, her husband hated the place and sought refuge at his old home at Denmark Hill. In the heart of Mayfair, Effie was able to indulge in her love of parties, high society and entertaining which she did on a grand style. In one letter alone she mentions Lady Chantrey, Lord Gray, Mr Eastlake, Lady Davy, Mr and Mrs Milman. Other letters mention Mr and Mrs Richmond, Lord Eastnor, Earl Somers, Sir Robert Inglis "very agreeable […] very religious and clever", Lady Inglis, Lord Glenelg, to name but a few. Osborne Gordon "from Oxford" dined with John and Effie on Saturday 2 December (1848) at their new home (James 135).

Not surprisingly, Effie became ill – she was suffering from a severe cold and cough, was losing weight and had developed an inflammation of the eye. Nevertheless, she and John were back at the family home on 12 December for a dinner at which Jane and John Pritchard, and Charles Woodd, a family friend, were present (JJR Diary). Her condition deteriorated over the Christmas period while staying at Denmark Hill (from 25 December to 5 January) under the authority of the older Ruskins. Little or no sympathy was shown to her. Mrs Gray came to visit her, and at the beginning of February 1849 mother and daughter returned to Perth, and Ruskin to Denmark Hill. Nine months elapsed before their reunion.

While Effie remained in Scotland, Ruskin set off on a continental tour with his parents. They travelled along a familiar route into Burgundy (Sens, Montbard, Dijon) and on to Geneva, Chambéry, Chamonix and many Alpine villages. Ruskin was given permission, reluctantly, by his parents to spend one month exploring the Higher Alps: with him were Couttet, his trusted guide, and George Hobbs, his valet. The parents remained anxiously in Geneva, awaiting their son's return. Ruskin needed time on his own to gather material for Modern Painters, volumes III and IV, especially the latter. It proved to be a good investment of his time, for several years later, Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Switzerland recommended Modern Painters IV, as containing "the most eloquent descriptions of alpine scenery yet written" (40). He wanted to familiarise himself with the different mountains and could only do this by absorbing their structure at first hand, by climbing and living among these peaks. He spent several days sleeping on the Montanvert, or working for three hours "on a peak of barren crag above a glacier […] at least 9,000 feet above sea" (5.xxviii) on the Matterhorn. Although Ruskin had spent three months in 1848 sketching detail of Normandy churches and cathedrals, – his rendering of a finial on the south porch of the west façade of the church of Saint-Lô to demonstrate the visual expression of the medieval carver’s deep spiritual feelings and relationship with his craft is a fine example – and had published subsequently The Seven Lamps of Architecture (complete text) in May 1849 containing many of those precise observations, he still felt that his ability to see was inadequate. He knew that his eye needed more training as he explained to his father in a letter from Courmayeur, in the Val d’Osta against the backdrop of Mont Blanc, on 29 July 1849:

I am quite unable to speak with justice – or think with clearness – of this marvellous view. One is so unused to see a mass like that of Mont Blanc without any snow that all my ideas and modes of estimating size were at fault. I only felt overpowered by it, and that – as with the porch of Rouen Cathedral – look as I would, I could not see it. I had not mind enough to grasp it or meet it. I tried in vain to fix some of its main features on my memory [5.xxvi]

As the end of his one-month’s "leave" was approaching, Ruskin requested an extension. He needed more time, always a recurring theme. Although anxious about their son’s health, the parents agreed but only on account of the reassuring presence of both Osborne Gordon and John Pritchard who were staying in Chamonix (Collingwood, Life, p. 116). Thus perhaps unknowingly, both Gordon and Pritchard were instrumental in influencing the course of events and contributing to Ruskin’s career.

Last modified 12 March 2020