When Ruskin was eventually reunited with his wife, another tour was planned, but this time without his parents. Effie wanted to go to Venice. She took as her companion Charlotte Ker, a neighbour from Perth: Ruskin was accompanied by his servant George Hobbs, and joined en route by the ever-faithful Couttet. As always, John James financed the entire trip for everyone. Leaving England in October, the party travelled through France to Chamonix, on through Switzerland, crossing the war-torn Lombardo-Veneto region overrun and occupied by Austrian and Croatian troops under the rule of the Austrian field marshal Count Joseph Radetzky (1766-1858). They eventually arrived at their hotel, the Danieli, in central Venice, close to St Mark's Square. That would be their headquarters until the end of March 1850 by which time Ruskin would have completed much of his work on the first volume of The Stones of Venice.

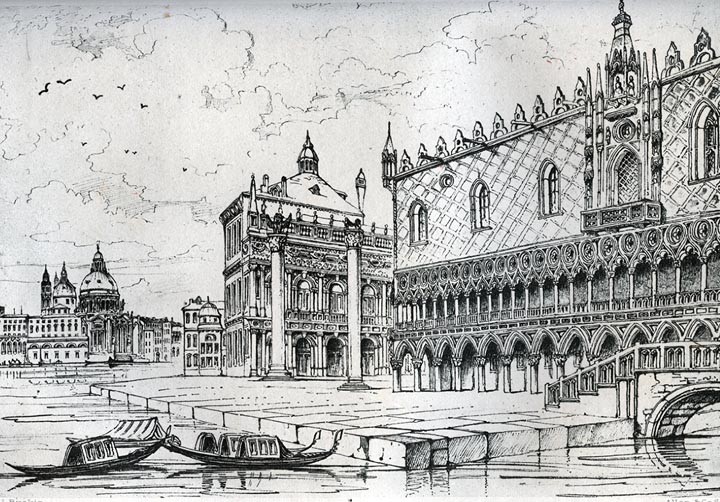

The Ducal Palace in Ruskin’s early and late styles: Left: The Ducal Palace, Venice. 1835. Source: 35.182. Right: The Ducal Palace. Renaissance Capitals of the Loggia. Watercolour. 1853. Source: 11.348 [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Effie had experienced considerable discomfort and hardship during the three-month delayed honeymoon tour of Normandy in 1848, staying in many cold, flea-infested, dirty hotels or lodging houses, and travelling long distances in badly sprung carriages. But in Venice, established in one place, she organised her own time more or less as she wished, with parties, balls, invitations to lunch and dinner, to soirées while her husband pored over his "stones". Her serious husband, engrossed in his work, seemed oblivious to her flirtations with the officers, with Prince Troubetzkoi, with Marquis Selvatico, President of the Venetian Academy, and particularly with the Austrian officer, Charles Paulizza. For selfish reasons, Ruskin encouraged Effie to socialise independently: he wanted to have as much time as possible on his own to devote himself to his research. She thrived on introductions: social life was essential to her happiness.

It was thanks to John Murray, publisher of the series of famous travel Handbooks, that Effie received a letter of introduction, in mid-December 1849, to "a Mr Rawdon Brown who had been residing some time in Venice" (Lutyens1 89). Rawdon Lubbock Brown (1806-1883) first took up residence in Venice at the age of twenty-seven and stayed there for the remaining fifty years of his life. He was an eccentric English bachelor, a man of exquisite taste with a passion for collecting. Brown immediately liked Effie, even preferred her to Ruskin, and confidences were soon exchanged. A few weeks later, Brown introduced Effie to a close friend of his in Venice, a wealthy Englishman, Colonel Edward Cheney (1803-1884).

A nice Venetian servant received us and we found the Palace in most beautiful order for us to see. It was fitted up so splendidly, a mixture of Italian taste & English comforts. There were cabinets of gems, fine pictures, statues and I don’t know what all. The marble floors were all covered with fine crimson cloth and nice coal fires blazing. I am quite astonished he, Col. C., was not terrified to leave such valuable property so open and the place so insecure but to see the cleanliness & propriety of everything you would have thought that the master intended to be back to dinner. [Lutyens 108]

These were Effie's first impressions of her visit to the Palazzo Soranzo-Piovene on the Grand Canal. It was on a bitterly cold winter’s day when John and Effie Ruskin were taken by Rawdon Brown to see the Palazzo during the absence of the tenant. It was greatly under-used, for Cheney resided in it only occasionally, sometimes just once a year. His main residence was elsewhere.

But this was not the first time that Ruskin had met Cheney. In his diary of 3 May 1844, Ruskin noted a visit from Cheney and his brother: "Cheney came out with his brother; he is a fine fellow, the brother quiet and commonplace. Didn't seem to like Turner" (Diaries, I, 274).

Edward Cheney and his two other bachelor brothers, Robert-Henry Cheney (1799-1866) and Ralph Cheney (1809-1869) formed a close-knit family unit and were devoted to each other. There were also two sisters: Harriet Margaret Cheney (died aged forty-six years in 1852) who married Robert Pigot, and Frederica Cheney who, on 27 February 1822, married Capel Cure of Blake Hall, Essex. Frederica and Capel Cure produced four sons and two daughters. The Cheneys' London home was at 4 Audley Square, in the heart of Mayfair: their country residence was Badger Hall, in the tiny village of Badger, in Shropshire. On the death of their father, Lieutenant-General Robert Cheney in 1820, the property had passed to his eldest son Robert-Henry: on his death in 1866 it was inherited by Edward. Badger Hall subsequently passed to Colonel Alfred Capel Cure (1826-1896), the second son of Frederica and Capel Cure.

The Cheneys were a cultured family, more interested in collecting and practising art than in fox-hunting and shooting. Their artistic talent was fostered by Harriet Cheney (mother of the five Cheney children) who, as Miss Harriet Carr, had had lessons in watercolour painting from John 'Warwick' Smith (1749-1831). She worked with Smith in Italy, acquiring skills in portrait and landscape painting, as well as an enduring love of Italy and its culture. So successful was Harriet Cheney that she is honoured in her own right as a painter in Bénézit's famous Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs de tous les temps et de tous les pays.

Staffordshire-born landscape painter Peter de Wint (1784-1849) enjoyed the patronage of the Cheneys (as well as other Shropshire/Staffordshire families such as the Clives of Oakley Park, Ludlow, and the Powis family). He often stayed with them during the summer as their private drawing master. The Cheneys also frequented other leading British artists of the day, including Edward Lear, Henry Bright, William Leighton Leitch (1804-1883) and Thomas Henry Cromek (1809-1873).

The catalyst for the development of the artistic propensities of Robert-Henry and Edward Cheney was the untimely death of their father Lt.-Gen. Robert Cheney in 1820. Robert-Henry had to abandon his studies at Oriel College, Oxford, and return to Badger to assume responsibility for the estate he had inherited. Harriet Cheney asserted to a much greater extent her influence. She transmitted her taste for Italy and art to her eldest sons in particular and all three shared closely her artistic interests. Mother and two sons visited Naples in 1823 and shortly after settled in the Palazzo Sciarra, on the elegant and fashionable Via del Corso, in Rome.

Sir William Gell by Cornelius Varley (1781-1873). 1816. Pencil on paper. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Although Edward Cheney, after studying at Sandhurst, flirted with army life, he quickly found his vocation in the world of eccentric, literary, and artistic people. In Naples, he found members of the Dilettanti Society, a society of wealthy gentlemen and patrons of the arts, particularly classical archaeology. Most prominent was Sir William Gell (1778-1836), the distinguished antiquary, archaeologist and travel writer. At the time, Sir William was living in Naples in the Villa Anspach, a palace on the Chiatamone overlooking the bay. But he was not alone. His intimate and colourful companions were the Hon. Keppel Craven, thought to be the illegitimate son of Lady Craven who had left England in a hurry and a flurry of scandal, and Sir William Drummond, a diplomat and scholar. To what extent the three men enjoyed "the closest bonds of friendship" can be surmised from their burial in a single tomb in the Protestant cemetery in Naples (Jenkins 305-06).

This powerful engagement with Italy continued and the Cheneys became well established in Anglo-Italian society, in Naples, Rome, Forence and Venice. It was at the Palazzo Barbarini in Rome, at the invitation of Lady Coventry and her daughter Lady Augusta, that Edward Cheney first met Richard Monckton Milnes in 1834: the two became lifelong friends (Monckton Milnes). The widowed Cheney mother and sons were received in the great Roman houses such as the Sermoneta/Caetani family.

But it would be wrong to convey the impression that the Cheneys spent all their time in society. Edward, (Robert) Henry and Harriet Cheney painted and sketched the villas, palaces and landscapes of Italy. The two brothers worked together so closely that individual attributions are not always easy to ascertain, such as their fine Roman watercolours, Villa Albani and Villa Conti, in the early nineteenth century.

A few years prior to the death of his mother in 1848, Edward acquired the rambling Palazzo Soranzo-Piovene in Venice, the city that became to him, in the words of R. Monckton Milnes, "a homeland of antiquity and art" (Monckton Milnes).

In late March 1850, it was with a heavy heart that Effie left Venice by gondola for the station to begin the return journey to England, clutching a brooch that Brown had given her as a present (Hilton 146). Ruskin continued his important work on the couple’s return to England in April 1850, and throughout the summer. It was a huge undertaking and any interruption in this intensive Venetian work could have been detrimental to the complex, creative process involving maintaining and organising a large corpus of detailed information. Understandably, Ruskin was not enthusiastic about any impediment or delay occasioned by social engagements. But he did, however reluctantly, accept invitations from John and Jane Pritchard and from Edward Cheney to take a short break at their Shropshire residences. Effie and John Ruskin spent two days with the Pritchards at Bank House, Broseley, between 15 and 17 August 1850, followed immediately by a short stay at Badger Hall from 17 until 20 or 21 August.

Two views of Wenlock Abbey in 1778, from engravings after Paul Sandby's drawings. In the left-hand one, the house is on the left; in the right-hand one, it is on the right. Source: Gaskell, Spring in a Shropshire Abbey, frontispiece, and facing p. 202.

From Broseley, it was a short carriage-ride to Wenlock Abbey, situated in the small market town of Much Wenlock, a distance of no more than three miles. Wenlock Abbey (technically a priory, but known for centuries as an abbey) was owned, at the time, by Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, 6th Baronet (1820-1885), a patron of J. M. W. Turner. Turner had worked in Shropshire in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, sketching scenes at Bridgnorth, Bromfield, Buildwas Abbey, Coalbrookdale, Ludlow, Shrewsbury and Wenlock Abbey.

"The Abbey Farmery" (the house). Source: Gaskell, Old Shropshire Life, facing p. 150.

The Williams-Wynn family seat was at Wynnstay in north Wales and their Wenlock Abbey property was nothing more than a much neglected, derelict, vandalised farmhouse (the former abbot’s house), set among the picturesque ruins of the former Cluniac priory destroyed in 1540 at the time of the Dissolution of the monasteries. It had inspired artists such as John Sell Cotman, Moses Griffiths, Paul Sandy Munn, Edward Pryce Owen, Paul Sandby and Peter De Wint. Perhaps there was hope for the incompatible Ruskin marriage, as Effie always delighted in discovering fresh places and described Wenlock Abbey, in a letter of 18 August 1850 to her mother, as "a fine ruin", and the country around as "very rich and flourishing" (T110, Lancaster). But the visit only served to highlight the couple's differences.

For Ruskin, Wenlock Abbey was much more than "a fine ruin". Besides, his hero Turner had worked there. While Effie wandered among the ancient stones, doing her best to avoid the brambles that could tear her fine long dress, her husband seized the opportunity to continue working on his Venetian project and to incorporate Wenlock Abbey in a comparative context in relation to Italy. He took with him his precious notebooks that he had been using in Venice earlier in the year: buried among them we find a scribbled note in his hand at the top of folio 1: "Some notes of Wenlock. p. 188" (Ref. Ms T7B, folio 1 – transcript of John Ruskin's Diary of 1850, Lancaster. See also in The Ruskin the microfilm of the original manuscript reference: John Ruskin Architectural note-book, Italy, 1850-51 ['M2'] (1 reel) Yale: Yale University Library, 1978 (T187a). See Notebook M2 p. 188.). I was expecting to find detailed architectural descriptions and measurements on the page in question in the style of so much of The Stones of Venice. However, page 188 consists of two sheets, right-hand and left-hand, with sketches of parts of Wenlock Abbey, plus comments, some of which are illegible and very faint.

Chapter House, Wenlock Priory. By Whymper.

Ruskin spent most of his time in the jewel of the ruins, the remarkably well-preserved chapter house with its exceptionally fine Norman carving, blind arcading and mouldings. There he sketched the recessed rounded arches decorated with zigzag work within which each cut "is worked into a small trefoiled arch, with an incision round it to mark its outline, and another slight incision above, expressing the angle of the first cutting" (9.321). His sketch, described erroneously by Ruskin as "from the refectory [sic] of Wenlock Abbey" and entitled Mouldings from Refectory of Wenlock Abbey, was placed alongside the edge decoration of a fourteenth-century Niche of the Tomb of Can Signorio della Scala, Verona, in volume one of The Stones of Venice (Plate IX, figs 7 & 10, facing 9.318). Whereas the teeth in the Verona tomb "had in distance the effect of a zigzag", at Wenlock Abbey "this zigzag effect is seized upon and developed, but with the easiest and roughest work; the angular incision being a mere limiting line" (9.321-22). Ruskin demonstrates how the arch at Wenlock Abbey "is an example of the simplest decoration of the recesses or inward angles between the pyramids; that is to say, of a simple hacked edge [...], the cuts being decorated instead of the points" (9.321).

On the left-hand sheet of page 188 of his Venetian notebook, Ruskin sketched one of the blind arches on the north wall of the chapter house, which James Charles Armytage subsequently engraved as figure 10 of Plate IX. It is interesting to compare Ruskin's original, detailed sketch with Armytage's interpretation of it with reduced and simplified flat features that do not do justice to the gothic carving or Ruskin's rendering. On that same sheet Ruskin also sketched detail of the carved cushion capital (a form often used on small shafts) of the left column supporting the arch as well as the decorative carving of the capitals on a double column. A detail that particularly interested him also, and which he sketched on that same sheet, was the hollow moulding studded with balls (like a belt or chain) that is used here in profusion on the blind arcading on the south wall.

Ruskin's writing, in pencil, mostly to the right of the drawing of the arch if it is held the right way up, is fairly faint and in places illegible. Here is a transcription suggested by Ian Bliss and colleagues: "Wenlock Abbey/a/hollow/ [cornelimes?]/ has balls/ ab/ vertical the dotted line through/ profile joint the wall line [through?]/ [of?]/ pilaster b 2/bb 2/capital base/ round/ [?]" ("Ruskin's Venetian Notebooks 1849-1850," electronic edition, [M2.188].) On the right-hand sheet of page 188, Ruskin sketched the intricate, interlacing blind arches on the north wall of the chapter house but did not use these for his published works.

Left: Edge Decoration at Wenlock Priory sketched by John Ruskin, engraved by J. C. Armytage (9.facing 318, plate IX, fig. 10), showing the "zigzag effect" (9.321), an example of "the simplest decoration of the recesses" in which each "is worked into a small trefoiled arch, with an incision round it to mark its outline, and another slight incision above, expressing the angle of the first cutting" (9.321). Right: Blind arcade on the north wall of the Chapter House, Wenlock Priory, showing Ruskin’s "zigzag effect". Photograph by Cynthia Gamble, 2014.

In that same volume of The Stones of Venice, a copy of which was sent to Shropshire friends Osborne Gordon, Edward Cheney and Richard Fall, Ruskin also included his sketches of two types of dripstone from Wenlock Abbey (9.97, figs. g & h). The types of dripstone were used to demonstrate the changes in the curve of the dripstone adapted to the weather, climate and to the amount of rain in a particular country or region. Ruskin often considered art and architecture in a European context – around a Franco-Italian-Swiss-British axis – and was constantly making links and connections. The Wenlock dripstones are part of that process and set in relation to others in Salisbury, Lisieux, Milan and Como.

From Wenlock Abbey, and before returning to Broseley, Effie and John Ruskin drove on, in the steps of Turner, down the very steep slopes leading to the banks of the river Severn, over the famous iron bridge at Ironbridge, to Coalbrookdale and the Severn Gorge, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, with its mines, factories, foundries and furnaces.

Limekiln at Coalbrookdale. by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851). c. 1797. Oil on Panel, 28.9 x 40.3 cm. Courtesy Yale Center for British Art B1981.25.636. Paul Mellon Collection.

Turner’s magnificent oil on canvas Limekiln at Coalbrookdale, dating from about 1797, depicts a dark, evening landscape out of which the fiery lights of the furnace, to the left of the image, attract the viewer’s attention. The sharp contrast between the tranquillity of medieval Wenlock Abbey and the industrial part of Shropshire only four or five miles away, and between the couple, was striking. Coalbrookdale was one of the great sites of the modern age, where iron ore had first been smelted by Abraham Darby and whose Quaker family remained the main philanthropic employer into the nineteenth century, where there were great furnaces and foundries, where there was work day and night and prosperity, where there were houses for workers and managers. Its achievements were known and admired throughout the world. The best fireplaces, stoves and gates came from Coalbrookdale. The owner, a proud industrialist, may have given the young Ruskins a guided tour of the large site and explained the various functions. The reactions of the couple were, however, very different.

Ruskin, the great philanthropist and social reformer, engaged in serious conversation with the "master of ironworks", and enquired more deeply about the conditions of the workers. In his Venetian notebook, Ruskin wrote, "I was told by master of ironworks at Coalbrookdale that the men employed in the severe work got about £2 a week, and that he had known a family in the receipt of 400 a year: but that they were improvident." (John Ruskin, Architectural note-book, Italy, 1850-51 ['M2'] (1 reel), Yale University Library, Yale, 1978, folio 186, microfilm, Lancaster. My transcription differs from that in both Lancaster Ms T7B, folio 186, and in "Ruskin's Venetian Notebooks 1849-50" [M2.186], ed. by Ian Bliss, Roger Garside and Ray Haslam.)

For Effie, the ironworks were "hideous" and perhaps a little frightening for this delicate, privileged, inexperienced, unworldly woman. She was totally unprepared for the sight that awaited her. She had been provided with a protective garment over her summer dress to protect her from the intense heat and sparks, and almost as a voyeur she approached the furnaces as closely as possible. She was fascinated by the muscular, semi-naked bodies of the burly workmen, dripping with sweat. In contrast, her slim, often-sickly husband would have been dressed in his dark suit, the model city gent. Effie had clearly listened to the commentaries and explanations, and observed and understood the industrial process and the role of the "sands". She wrote on 18 August 1850 to her mother about her experience with considerable insight: "I saw the redhot metal flowing like a river into the sands prepared for it and in other places rushing out […] every where around. […] The workmen were almost entirely naked and pouring with perspiration, much wetter than if they had been thrown into a pond" (T110, Lancaster).

Within a small geographical area, the couple had experienced the contrasting old and the new, picturesque Wenlock Abbey and the new industrial age at Coalbrookdale. The day had also highlighted the contrasts in their relationship that would manifest themselves even more greatly. For Ruskin, it contributed to his architectural knowledge and to the development of his intense, lifelong social conscience that would permeate his writings. But for Effie, it was a world away from her life as a society hostess at 31 Park Street, in the heart of Mayfair.

After their stay at the Pritchards in Broseley, John and Effie Ruskin went to Badger, at the invitation of the Cheney family, arriving on 17 August 1850. Badger, a small rural parish with approximately 160 inhabitants, was about ten miles from the Pritchard family home and Bank in Broseley. This small settlement comprised a church, rectory, Hall, a few houses and farms. Unlike many villages, there was no public house in the parish. It would be difficult to imagine Ruskin at ease in Badger Hall that had been refashioned by the famous architect James Wyatt in the late eighteenth century, in the neo-classical style on the orders of the wealthy art connoisseur Isaac Hawkins Browne. It was a rather austere building, isolated from the village, and set in extensive parkland. Wyatt retained the service buildings dating from the late seventeenth century that stood to the south: he added a block of eight bays and three storeys, mainly of brick, on the north end of the old Hall. A conservatory was also built. Fine plasterwork by Joseph Rose of London included a frieze depicting classical gods, heroes and Shakespearean characters. Inside were treasures that had been collected by the Cheneys from (mainly) Italy. One room, full of classical busts, bronzes, Old Master paintings, Tiepolo drawings and sketches, furniture, was designed specifically as a museum. In the Hall were objets d'art, coins, medals, faïence, prints and Rembrandt etchings, not forgetting a huge library decorated – as was also the dining room – with chiaroscuro paintings by Robert Smirke (1752-1845). The service buildings of the old Hall were refurbished as a private house in the early 1980s after the demolition of most of Badger Hall in c. 1953 (VCH Shropshire, x, 216).

About one mile away was Badger Dingle, the Cheneys' private, forty-acre picturesque, landscaped hollow or dell, park, wood and pleasure ground. It was far more elaborate than anything ever seen, and was much admired and envied. Effie was fascinated by the Dingle, and described it and Badger Hall to her mother:

This is a very fine place and the Dingle close to the house is one of the curios of the country and open to the public. It is exceedingly like Modlyn and Hawthornden a deep crevice with rocks, wooded banks, trees and everything in the greatest abundance the gardens and flower gardens beat anything I ever saw such masses of colour and multitudes of flowers, and the rooms inside the house are furnished with the greatest elegance and richness full of Greek & Italian art with many gems from Venice accad. and Venice Wells in the centre of the Conservatories spouting water. [T110, Lancaster]

So Badger Dingle was already open to the public in 1850, according to Effie. It became a popular attraction, especially for the town dwellers of Wolverhampton and Birmingham on their workers' outings. The Dingle had been cut through deep, steep red sandstone: a sheer drop of several yards, down the cliff face, led to the pools that had been created for boating, bathing and recreation. There were waterfalls, along with caves and gateways, and a mill near one of the dams. Reminiscent of Turner's impressive St Gothard's Pass was a rock cut path, with a bridge, that led down a steep gorge from the road.

Badger Dingle The artist was either Robert Henry Cheney (1801-1866) or Edward Cheney (1803-1884). 1847. Pen and ink. private collection.

The Dingle was planted with exotic shrubs and trees, Alpine plants, colourful American rhododendrons and azaleas, some protruding from the rock faces. Down in the cool of the Dingle was an ice house, hewn into the perpendicular rock. Inside, along a passage, was an enormous egg-shaped cavity used for storing ice taken from a nearby pool in midwinter. The sophisticated ice house – the equivalent of a modern day freezer – was constructed in such a way as to be insulated against temperature changes and ensured that the ice remained solid for an entire year. This was a necessary feature for any great house of the day. Ruskin may have been inspired by the Badger ice house when he created his own on his Brantwood estate more than two decades later. Collingwood recalled how Ruskin's ice house "was tunnelled at vast expense into the rock and filled at more expense with the best ice" (350). As well as providing ice for the Brantwood household, it was intended for charitable purposes, "to supply invalids in the neighbourhood". But to what extent it was successful seems dubious, for Collingwood relates that the result of Ruskin's efforts was "nothing but a puddle of dirty water".

A classical folly known as The Temple, built in 1783, was also designed by Wyatt. It was placed at the end of a long, tree-lined, private carriageway, a striking vista linking Badger Hall with the folly. The rotunda-shaped Doric Temple, comprising ground floor and first floor linked by a spiral staircase and overlooking a private lake within Badger Dingle, was used as a summerhouse, teahouse and architectural ornament. The Temple was in use by the Cheney family and their descendants until the 1930s: it was given a new lease of life when it was splendidly refurbished as a holiday cottage in the late twentieth century.

Ruskin would probably have visited, and perhaps disapproved of the little church of St Giles, most of which was rebuilt in 1833-1834: in Pevsner's opinion, "in a poor Gothic style" (67).

In April 1851, Effie and John Ruskin made a very brief visit to Badger Hall where all three Cheney brothers were in residence (Lutyens1 173). Effie enjoyed her visit immensely, and consolidated her friendship with Edward Cheney in particular. He would become a loyal friend to her over the years and an ally in her troubles with Ruskin and his parents.

Later in the year, Ruskin returned to Oxford for a baptism. In spite of Ruskin’s strong dislike, even hatred of babies and very young children (Effie revealed to Rawdon Brown that her husband "hates children and does not wish any children to interfere with his plans of studies" [Lutyens1 171]), he attended the baptism on 2 October 1850 of Henry Dyke Acland, the first-born son of Henry Acland. It must have been an ordeal for Ruskin, and it is difficult to imagine him showing any interest whatsoever in the baby, let alone holding it. He would have tolerated the occasion out of deference to Acland, one of his closest Oxford friends who had qualified as a doctor in 1846 and at the time of this baptism had a flourishing medical practice in Oxford. In 1851, Acland also held the part-time post of Radcliffe Librarian: in 1857, he was appointed Regius Professor of Medicine.

Ruskin took advantage of the occasion to meet Gordon and to discuss at length "the religious state of the University". It was not a theological question that was preoccupying Gordon. The problem was the dull English Sunday and the difficulties undergraduates experienced in coping with it. Gordon "did not know what to do with the young men on Sunday", and "could not recommend them to go to church", he told Ruskin (Diaries, II, 467). After early morning prayers, the students went to breakfast and "sat over it for three hours". Gordon wanted the Sunday timetable to be modified to help the students cope with the boredom of the day. His suggestion was pragmatic: "If the Dean would have a cathedral service at 10 o’clock, it would lift them over so much of the day" (Diaries, II, 467). The very use of "lift them over the day" suggests the seriousness of the problem. It is likely that Ruskin sympathised, for he was obliged to conform to a strict Sunday regime when he was with his parents. His evangelical mother would have been horrified, had she known of Gordon’s views: she had already expressed strong disapproval of what she perceived to be his Catholic tendencies in her letter of 12 June 1843, to which we have already referred. The problems persisted, for, in 1861, Edward Bouverie Pusey, Regius Professor of Hebrew at the University of Oxford and Canon of Christ Church, denounced the behaviour of Christ Church undergraduates on Sunday mornings, spent in eating and drinking "and, I suppose, smoking", to the detriment of their attendance at the Cathedral services (Bill and Mason 166).

An Act of Parliament in 1829 had accorded Catholics greater rights to participate more fully in public life: numbers were increasing steadily. But the direct involvement – or interference – of the Italian Pope Pius IX (1792-1878) in the appointment of Dr Nicholas Wiseman on 29 September 1850 as Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, with twelve English Bishops under his authority, thus re-establishing a Catholic hierarchy in England, was a catalyst that infuriated many senior churchmen and inflamed an already tense situation. Oxbridge was at the centre of the debate on the march of Catholicism. Ruskin and Effie discussed the situation with Dr Whewell, Master of Trinity College Cambridge, who told them that his students were "violent about the Papal aggressions (Hilton 150)". Gordon, although a moderate High Churchman, was part of an Oxford deputation to Queen Victoria opposing "papal aggression". They did not, however, manage to effect change.

Last modified 12 March 2020