Introduction

Christian Socialism emerged after the collapse of Chartism in 1848 as a reform movement in England in response to the political, economic, social, and religious developments in the mid-Victorian period. Influenced by Thomas Carlyle, Robert Southey, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, as well as Fourierite, Saint-Simonian and Owenite socialism, rather than by the ideas of Karl Marx, the Victorian Christian Socialists called for cross-class communitarian co-operation instead of unrestrained laissez-faire competition in industrial relations. Earlier forerunners of the Christian Socialist movement in Victorian England include radical dissent movements in the Middle Ages (the Peasants' Revolt, John Wycliffe and Lollards), Levellers and Diggers in the time of the English civil war (1642-1651), and the Corresponding Societies of the 1790s.

Founders and adherents

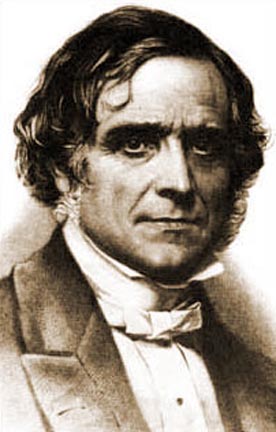

Left: Frederick Denison Maurice by Lowes Dickinson (1873). Right Charles Kingsley by Thomas Woolner (1874). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The term 'Christian Socialism' was first used in 1848 by the Anglican theologian and priest Frederick Denison Maurice (1805-1872), the most important promoter of the movement and a personal and ideological inspiration for many late-Victorian Christian Socialists. Maurice, together with Ludlow and Kingsley believed in the compatibility of Christianity with socialism.

However, the real founder of the Christian Socialist movement was John Malcolm Ludlow (1821-1911), a convinced Socialist, who had known Charles Fourier and other French socialists. Both men were appalled by the widespread poverty and the economic plight of the poor and working class in the 1830s and 1840s. They watched the emergence of the new political doctrine known as Socialism with hope and apprehension. Ludlow, who was also a devoted Christian, persuaded Maurice that 'the new Socialism must be Christianized'. (Cross 1009) Ludlow became the most efficient organiser and co-ordinator of the movement. He was also a co-founder and editor of the Christian Socialist newspaper, co-founder of the Working Men's College, and the first Chief Registrar of Friendly Societies.

The title-pages of some of Ludlow's writings: Christian Socialism and its Opponents, a lecture to the Workingmen's College, plus books on India and the 1857 mutiny plus two very different works, one on medieval epics and the other on women's role in the church. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Charles Kingsley (1819-1875) was a prominent Broad Church clergyman and controversialist who addressed the Condition-of-England question in his sermons, essays, tracts, novels and children's books. In 1848, in the year of revolution in Europe, Kingsley began to take an active interest in Christian Socialism, and wrote a number of papers and pamphlets in support of the movement.

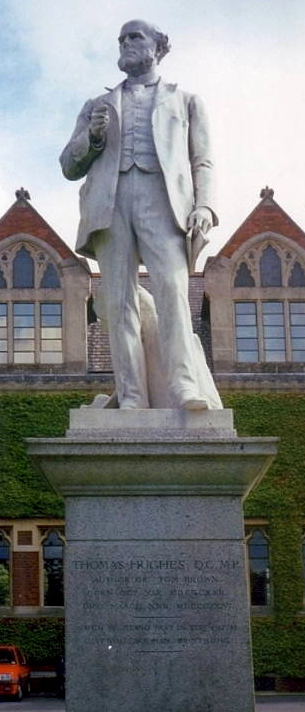

Thomas Hughes by Sir Thomas Brock (1899).

The principal later adherents were Thomas Hughes (1822-1896), a lawyer and author, Edward Vansittart Neale (1810-1892), a barrister and co-founder the first co-operative store in London; and Frederick James Furnivall (1825-1910), a philologist and one of the co-creators of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The Christian Socialist movement in mid-Victorian England retained a distinctly clerical aspect.

Views

The Christian Socialists criticised the system of uncontrolled, unregulated laissez-faire competition in industrial relations, but they did not propose any coherent economic doctrine or a programme of reforms. They believed that the Christian Gospel contains the key to the social question, particularly in its teaching of the brotherhood of man. The chief mission of the Christian Socialists was to win back the workingmen to the Church. Christian Socialism meant for them social, cross-class co-operation and partnership under the leadership of the Church.

Maurice, who was the most influential and highly charismatic member of the movement, wished to express the idea that socialism is a development and outcome of Christianity; and if it is to be effective, it must have a definite Christian basis. Maurice emphasised the Church's role in social reform against the injustices of capitalism.

In 1849, the group met a French refugee, Jules St. André le Chevalier (also known as Lechevalier, 1806-1862), a French utopian socialist, Saint-Simonian and Fourierist, who acquainted them with French socialism. In devising their Christian Socialist ideas Maurice and Ludlow were strongly influenced by Lechevalier, who propounded a view, which Maurice and Ludlow fully accepted, that “Christianity represented the true essence of Socialism as expressed in the principles of association or co-operation,” and “that the Church must concern itself with the problems in trade and industry where modern unbelief was rampant.” (Christensen 116)

Social agitation

On 10 April, 1848, after the failed Chartist demonstration at Kennington Common, Maurice, Ludlow and Kingsley issued a proclamation to the “Workmen of England,” which was signed by “A Working Parson” (Kingsley) It contained an expression of solidarity and sympathy with the labouring classes and a warning against widespread violence.

From 6 May 1848, Maurice, Kingsley and Ludlow published articles in a penny journal, Politics for the People. In the first issue Maurice argued that the virtues of liberty, fraternity and equality are inscribed in Christian teaching. Ludlow authored most of the articles under the pseudonym “John Townsend” or “J.T.,” Charles Kingsley, under the pseudonym “Parson Lot,” published “Letters to Chartists,” and Maurice signed his contributions as “A Clergyman.” The paper was primarily addressed to the “workmen of England,” but only five letters from working-class men were printed. As the journal could not reach the working-class readership, it was closed in July 1848 after seventeen numbers. Next the Christian Socialists published another journal, the Christian Socialist (2 Nov. 1850-25 June 1851), which promoted the Christian view of a socialist society. Ludlow as the editor began to diffuse the principles of co-operation by the practical application of Christianity to the purposes of trade and industry.

Tracts on Socialism

The group also produced a series of pamphlets under the title Tracts on Christian Socialism (1850-51), which was a manifesto of Christian Socialism addressed to both the working class and Anglican clergy. Maurice wrote: “I seriously believe that Christianity is the only foundation of Socialism, and that a true Socialism is the necessary result of a sound Christianity.” (Christensen 136) Society – he believed – is not merely made up of individuals. For the Christian Socialists society was an organic unity based on the principles of solidarity and co-operation.

All these publications were designed to promote the movement's views but they did not advocate a large-scale reform of any kind. What Maurice called for was the moral regeneration of individuals as a means of alleviating acute social problems. The Christian Socialists also appealed to the justice and charity of the rich.

Attitude to socialism

The Christian Socialists were inspired by Christian social teaching, French socialism and the Owenite co-operative socialism, but they were hardly socialists in the present meaning of the word. They criticised laissez-faire capitalist competition and proposed profit sharing between capitalists and workers as a way of improving the condition of the working class in a just, Christian society. Christian Socialism meant a co-operative commonwealth to be attained through voluntary effort. The theological foundations of Christian Socialism were formulated in Maurice's work, The Kingdom of Christ (1838), which argued that politics and religion cannot be separated and that the church should be committed to social questions. As a matter of fact, Maurice did not want to become a radical social reformer. He was a social conservative who tried to reinforce Christian values in a modern industrial society. As Cheryl Walsh pointed out:

He believed that the Kingdom of God was already in existence on earth, meaning that the existing social and political institutions were part of the Kingdom. Therefore, planning or advocating fundamental changes in the political system or the social structure would be to usurp the role of Christ, who was the Head of the Body of humanity. [358]

However, Maurice invented the phrase 'Christian Socialism' in protest against 'unsocial Christians and unchristian Socialists'. (White 283) His aim was to integrate the sacred sphere with the secular one; he attempted to 'christianise' socialism and to commit the clergy to active social work. As Edward Norman stated:

The Victorian Christian Socialists produced a radical departure from the received attitudes of the Church, both in their religious and in their social contentions, and their contribution to what Frederick Denison Maurice, their greatest thinker, called the 'humanising' of society, disclosed qualities of nobility and unusual discernment. [Norman 1]

The Christian Socialists stressed the pre-eminence of personality over all material conditions. For Christian Socialists socialism was a means and not an end; the end being the full development of an individual's inherent capabilities. To that end Maurice organised discussions with members of the labouring classes, for whom he expressed his sincere appreciation and respect.

Co-operative associations and educational establishments for workers

John Ludlow, who had seen organised labour associations in France, intended to start similar co-operative societies in England. He and several other Christian Socialists were not focused on the theological aspects of Christian Socialism and tried to form workers' co-partnership associations. In February 1850, the Christian Socialists helped to found a Working Tailors' Association, with Walter Cooper as manager. The principal aim of the Association was non-competitive joint work and shared profits.

Later in 1850, the Christian Socialists formed the Society for the Promotion of Working Men's Associations, the aim of which was to promote some kind of working-class associations since co-operative societies could not sell products to non-members. In order to alleviate poverty among the labouring classes, Ludlow contributed to the passing of the Industrial and Provident Societies' Act of 1852, which provided for the creation of co-operative societies and mutual businesses in England. Thomas Hughes, Edward Neale, Lloyd Jones, and other members of the Christian Socialist group contributed to the establishment of the London Co-operative Store, with Lloyd Jones (1811–1886), a socialist, union activist and advocate of co-operation, as manager.

Other initiatives of the Christian Socialists included a night school for working men and women in Little Ormond Yard. In 1848, Maurice was one of the founders of Queen's College, London, which offered higher education to women. Queen's was the first institution in Great Britain where young women could study and gain academic qualifications. Maurice also supported the idea of workers' education. He founded and became the first principal of the Working Men's College in London.

The Working Men's College

In 1854, F. D. Maurice founded the Working Men’s College (WMC) in London, which became the earliest adult education institution in Britain running evening classes for workers. Its roll of teachers and supporters included F. D. Maurice (its founder), Charles Kingsley, Thomas Hughes, John Ruskin, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, Thomas Henry Huxley, and Sir John Lubbock (Lord Avebury). The aim of the College was to provide liberal education to disadvantaged adult learners, mostly artisans and manual workers. Previously, liberal education was generally available to the wealthy.

The College opened with an enrollment of 176 students. The most popular classes were Languages, English Grammar, Mathematics, Drawing whereas History, Law, Politics and the Physical Sciences attracted smaller attendance. (Harrison 59) In November 1854, John Ruskin began to teach elementary and landscape drawing on each Thursday from 7 p.m. to 9. p.m. The Working Men's College proved to be one of the most successful projects of the Christian Socialists.

Discord

At that time serious differences of views emerged among the leadership of the Christian Socialists. Maurice, Ludlow, Kingsley and Neale were divided about the future character of the movement. Neale and Jones wanted to extend the scheme of co-operative associations by sponsoring not only producers' co-operatives but also consumers' co-operatives. Maurice and Ludlow did not support this plan. In consequence, Ludlow resigned from the Society for Promoting Working Men's Association, and also resigned from the Christian Socialist when it changed its name to A Journal of Association.

Maurice, who was born a Unitarian and converted to Anglicanism when he was a university student, began to repudiate the term 'Christian socialism' in the 1850s because he saw that the movement was gradually losing its religious content. He became less interested in promoting co-operative associations, but concentrated his efforts on theological matters. Maurice, it seems, was not keen on a socialist redistribution of wealth or state ownership of the means of production. His goal was to create social harmony in place of social discord through the application of Christian principles. (Phillips xvi). Ludlow and Neale had different views about the aims of the Christian Socialist movement.

After 1854 Christian Socialism ceased to be an organised movement, but the influence of its original leaders and of their disciples on both the clergy and lay people in the second half of the 19th century was very profound. From the mid-1850 to the late 1870s the Christian Socialist movement fell to a standstill.

Christian Socialist revival in late Victorian Britain

The Christian Socialist movement dissolved in the mid 1850s and re-emerged in the late 1870s in a number of organisations which prompted social concern in the Anglican Church and other Christian denominations as well as influenced the growing labour movement and co-operative societies. During the outburst of socialist agitation in the 1880s and 1890s numerous Christian socialist organisations and groupings were established in Britain. Most of them were short-lived and small, but some of them exerted a significant influence on social reforms in Britain.

Some of the late offshoots of mid-Victorian Christian Socialism included the Guild of St. Matthew as a parish communicants' society which may be regarded as a direct descendant of mid-Victorian Christian Socialism. Subsequently, the Christian Social Union, founded in 1889, became an offshoot of the Guild of St. Matthew. In the autumn of 1886 the newly-established Christian Socialist Society began holding public meetings in Bloomsbury, London, and in 1906, the Church Socialist League was formed.

The Guild of St. Matthew

The Guild of St. Matthew (GSM) was formed in 1877 by Stewart Headlam (1847-1924), a student of F. D. Maurice at Cambridge, then an Anglo-Catholic curate of St. Matthew's Bethnal Green in London. Headlam's objective was to combine the tradition of Christian Socialism, which he took from Maurice and Charles Kingsley, with the sacramental doctrine of high Anglicanism.

Headlam, like many reformers in late Victorian England understood the concept of Socialism as a reform movement. He once remarked: “Yes, I am a Socialist, but I thank God I am a Liberal as well.” (Inglis 273) He tried to convert clergymen to a more active interest in social problems, arguing that it was a Christian duty to work for land nationalisation, a progressive income tax, universal suffrage, and the abolition of a hereditary House of Lords. The GSM did not publicly support socialism until 1884. In 1884, the Guild presented the following resolution which had a distinct socialist bias:

That whereas the present contrast between the condition of the great body of workers who produce much and consume little and of those classes who produce little and consume much is contrary to the Christian doctrines of Brotherhood and Justice, this meeting urges on all Churchmen the duty of supporting such measures as will tend —

- To restore to the people the value which they give to the land;

- To bring about a better distribution of the wealth created by labour;

- To give the whole body of the people a voice in their own government; and

- To abolish false standards of worth and dignity. [Pelling 134]

Many Anglican clergymen openly identified themselves as Socialists, and believed that Socialism meant Christianity in its modern industrial development. They openly supported the GSM. One of its members, the Reverend Charles W. Stubbs, Dean of Ely, wrote in the 1890s about the urgent need for the “social mission of Christ's Church.” (Phillips 80) After a period of a great popularity, the Guild began to lose its members and supporters, and it was finally dissolved by Headlam in 1909.

The Christian Social Union

The Christian Social Union (CSU) was formed in Oxford in 1889 by two Anglo-Catholic clergymen, Henry Scott Holland (1847-1918) and Charles Gore (1853-1932). Like the Guild of St Matthew, it was open to clergy and laity. Under Holland's leadership the CSU sought to influence the high circles of the ecclesiastical polity in way similar to that of the Fabians who later sought to influence cabinet ministers and bureaucrats through permeation. (Pelling 135)

The Christian Social Union was the largest Christian socialist organisation which had 27 branches and a membership of 3,000 in 1895. (Parsons and More. 51)

However, as Anthony Dyson claims: “the leadership of the CSU was not socialist at all.” (Byer and Suggate 76). Likewise, Norman claimed that the Christian Social Union “was never committed to Socialism at all.” (173) The Union consisted exclusively of Anglicans, and its peak membership grew to 6,000, including a few bishops, but it had no members from the working class. Following the religious ideas of Maurice, the Christian Social Union focused on moral and religious priorities rather than on economic and political.

The Christian Social Union failed to attract the working-class masses. Efforts were made to establish a working-class organisation alongside the Christian Social Union and as a result the Christian Fellowship League was formed in 1897.

One of the significant achievements of the Christian Socialist theologians was the implementation of the university settlements, which were Christian missions established in slum areas of London and other big cities in England, where university students had an opportunity to have a direct contact with slum residents. One of such settlements was Toynbee Hall, founded in 1884. In Hoxton, the Christian Social Union opened its men’s and women’s hostels.

Socialist ideas of other Christian denominations

Interest in socialist ideas was not only limited to the Anglican Church. Other denominations and the British Catholic Church also expressed interest in social issues. The Methodists started the Forward Movement in 1891, and the Baptists formed the inter-denominational Christian Socialist Society (1886-1892), which had a more militant programme calling for the public control of land, capital and all means of production, distribution and exchange.

The inter-denominational (mostly Nonconformist) Christian Socialist League was formed in 1894 and was committed to collectivist socialism. Christian Social Brotherhood (1898-1903) was a Nonconformist successor of the Christian Socialist League. A Unitarian minister, John Trevor (1855-1930) created a socialist Labour Church movement in 1891. The Socialist Quaker Society (SQS, 1898-1924) was the longest-lasting Nonconformist socialist organisation, which aimed to educate members of the Society of Friends about socialism and promoted it as a solution to current social problems.

British Social Catholicism

The Roman Catholic Church was hostile to socialism in the late 1870s and 1880s. Socialists were strongly criticised in the 1878 encyclical Quod Apostolici Muneris, in which Pope Leo XIII had equated them with Communists and Nihilists. It was another encyclical, Rerum Novarum (1891), that started teaching on social questions in the Catholic Church, and Catholic attitudes to socialism slowly changed. Strangely enough, some conservative Protestants equated the threat of socialism with that of Catholicism in Britain.

Cardinal Manning, Archbishop of Westminster from 1865 to 1892, was an outstanding promoter of British Social Catholicism. He often expressed his concern for the social conditions of the poor and the situation of trade unions. During the London Dock Strike (1889), when 100,000 dockers went on strike for five weeks, he supported the workers and mediated in negotiations. However, he did not have socialist leanings. He opposed what he called subversive and destructive Continental socialism.

Social organisation is thoroughly English; socialism, on the contrary, is Continental. [...] I cannot be a socialist being an Englishman, and socialism having no existence in England. [The Bush Advocate 7]

However, Manning contributed significantly to the awakening of the British Catholic Church to social issues. The Roman Catholic Church in England was essentially a church of the poor, mostly Irish immigrants who lived in slums. Manning sponsored Catholic education for the poor and established orphanages and reformatories for Catholic children.

Irrespective of the development of the Catholic social thought, a few Roman Catholic socialist societies were established in Britain at the beginning of the 20th century. The Catholic Socialist Society was formed in Glasgow in 1906 by John Wheatley and William Regan. Its members, who were practising Catholics, propagated Christian Socialist ideas among the working classes. The Catholic Social Guild was founded in 1909 as a counterpart to the Anglican Christian Social Union. Inspired by the Catholic social movements in France, Belgium and Germany, it promoted interest in social questions among Catholics, and aided in the practical application of the Church's principles to existing social conditions.

Conclusion

Christian Socialism in the Victorian era was by no means a homogeneous movement. The Christian Socialist group, which was formed in mid-Victorian England by Frederick Denison Maurice, John Ludlow, Charles Kingsley and others, identified socialism with Christianity and was indebted to the tradition of continental (mostly French) socialism and English radicalism. Inspired by Chartism, it aimed to provide solutions to social ills through educational and moral change, and not change in political legislation.

Christian Socialism in the late Victorian period, which came from all backgrounds, Anglican, Nonconformist, as well as Anglo-Catholic and Roman Catholic, was never radical or revolutionary, but conservative, reformist and evolutionary. The Christian Socialists criticised the notion of the “ invisible hand” of the market, i.e. unrestrained laissez-faire capitalism. They also emphasised the collective responsibility of society to deal with economic problems, but they did not want to disestablish the prevailing social order. The Victorian Christian Socialists contributed to adult education, the co-operative movement, friendly societies and the labour movement. Christian Socialism lay a greater emphasis upon moral and social requirements of human life than other strands of Victorian socialism.

Related material

References References and Further Reading

Bayer, Oswald, Alan M. Suggate. Worship and Ethics: Lutherans and Anglicans in Dialogue. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1996.

Brose, Olive J. Frederick Denison Maurice: Rebellious Conformist. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1971.

“Cardinal Manning on Socialism,” Bush Advocate, VII (493), 11 July 1891.

Christensen, Torben. Origin and History of Christian Socialism 1848-1854. Aarhus: Universitetsforlaget I, 1962.

Cross, Frank Leslie and Elizabeth A. Livingstone, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Harrison, J. F. C. A History of the Working Men's College: 1854-1954. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1954.

Inglis, K. S. Churches and the Working Classes in Victorian England. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1963.

Jones, Peter d'Alroy. The Christian Socialist Revival 1877-1914: Religion, Class, and Social Conscience in Late-Victorian England. London: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Ludlow, John. John Ludlow: The Autobiography of a Christian Socialist. Edited and Introduced by John Murray. London: Frank Cass. 1981.

Masterman, N. C. J. M. Ludlow: Builder of Christian Socialism . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

McEntee, G. P. The Social Catholic Movement in Great Britain. New York: The Macmillan Co., 1927.

Norman, Edward. The Victorian Christian Socialists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Parsons, Gerald, ed. Religion in Victorian Britain: Controversies. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988.

Pelling, Henry. The Origins of the Labour Party, 1880-1900. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1954.

Phillips, Paul T. Kingdom on Earth: Anglo-American Social Christianity, 1880-1940. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996.

Raven, Charles E. Christian Socialism 1848-1854. London: MacMillan and Co., 1920.

Walsh, Cheryl. “ The Incarnation and the Christian Socialist Conscience in the Victorian Church of England,” Journal of British Studies 34(3), 1995), 351-374.

Young, David. F. D. Maurice and Unitarianism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

Last modified 24 February 2014