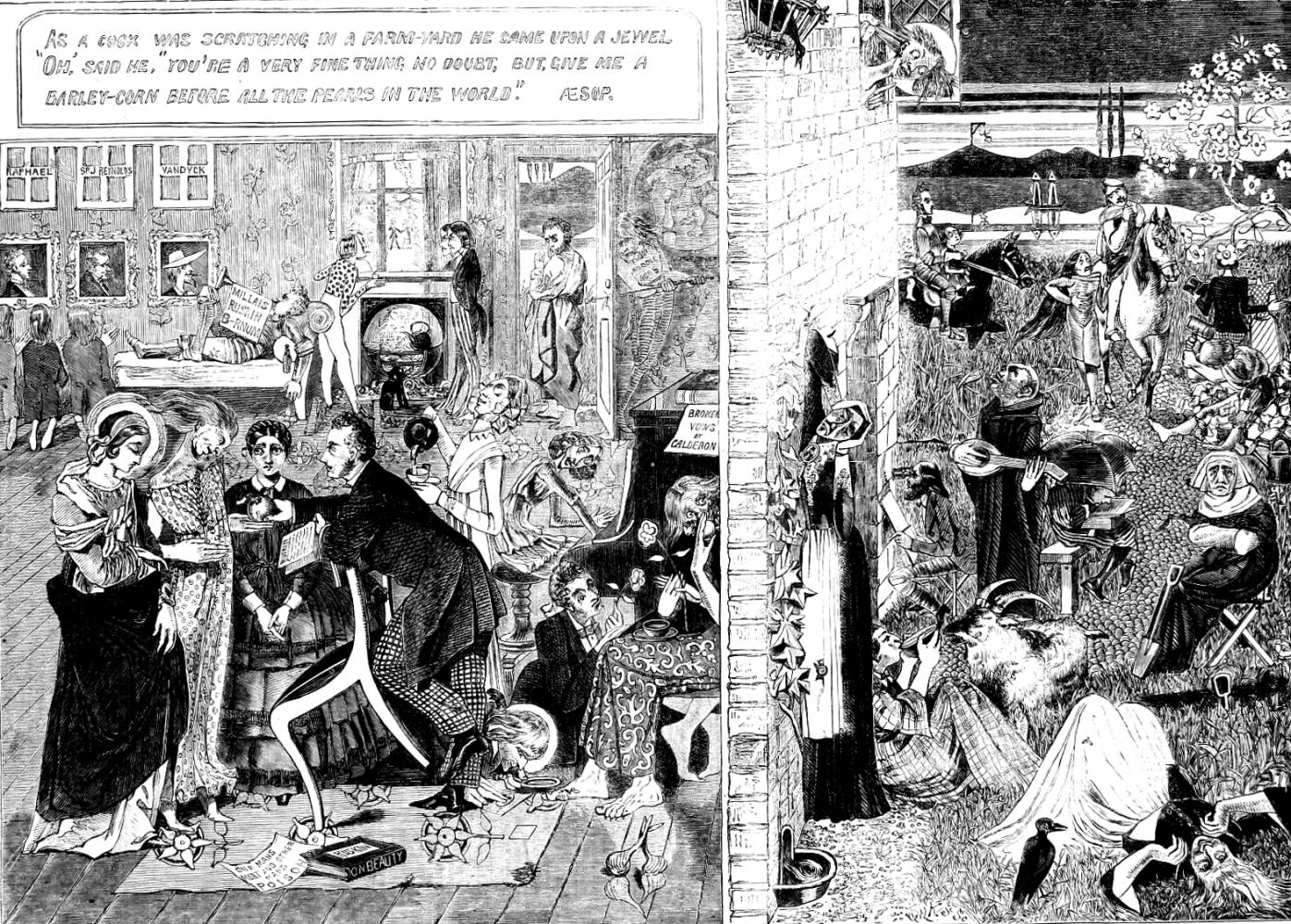

‘Almost from the outset, when “PRB” first appeared on three pictures exhibited in 1848 … Pre-Raphaelitism and its devotees have been satirized, parodied, caricatured … and made the subject of humorous spoofing …’ So writes William Fredeman in his analysis of Florence Claxton’s parody of Pre-Raphaelite painting in The Choice of Paris: An Idyll ( The Illustrated London News, 2 January 1860), and no-one could doubt the veracity of his claim (523).

Left: Claxton’s take on the Quattrocento anachronisms of Pre-Raphaelitism in The Choice of Paris. Right: Du Maurier’s arch reflection on the distortions of the Pre-Raphaelite style.

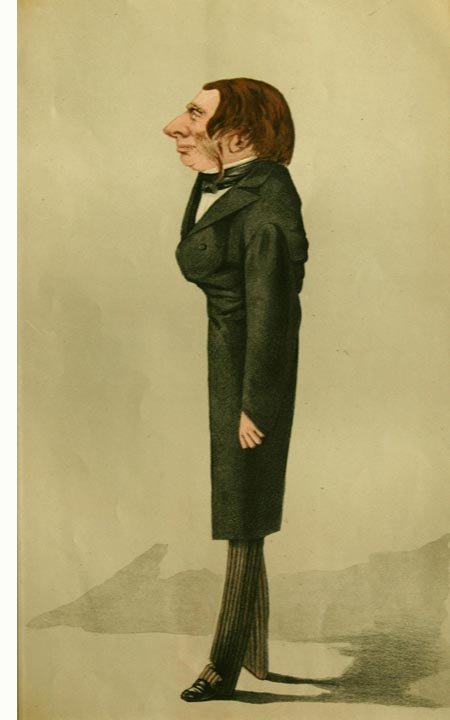

Indeed, visual mockery of the Pre-Raphaelites was widespread and took numerous forms. Florence Claxton’s parody was paralleled by John Waring’s satirical drawings in Poems Inspired by Certain Pictures, which ruthlessly ridicule the paintings exhibited in Manchester in 1857, and in A Legend of Camelot (1866, 1898) Du Maurier provided a comprehensive critique of all aspects of the Pre-Raphaelite style, lampooning its faux medievalism, its idealized beauty, its perspective, and even the exaggerated coiffeur of its models. There were also visual mockeries of the artists and their associates, with caricatures of J.E. Millais, William Holman Hunt and John Ruskin appearing in Vanity Fair (1872–2; 1879).

Left: Spy’s caricature of William Holman Hunt. Right: John Ruskin.

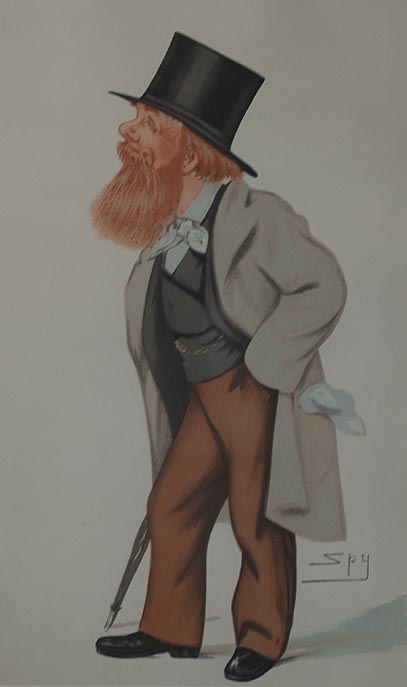

For sure, mocking the Pre-Raphaelite project was comedic fair game, and the Pre-Raphaelites even made fun of themselves, drawing caricatures of their appearance and their art: Edward Burne-Jones’s cartoon Unpainted Masterpieces is a prime example of self-deprecation, with the painter feebly looking on in despair as he searches for inspiration, while D. G. Rossetti’s elegy for his dead wombat is a highly amusing, mock-tearful reflection on his incompetence as a zoo-keeper (Birmingham City Museums and Art Gallery).

All of these satires point to the scepticism with which Pre-Raphaelitism was received, at the same time revealing the far from priggish or self-important attitudes of those who created the movement. It is interesting, moreover, to note how comedic-critical responses continued into the twentieth century, most notably in Max Beerbohm’s celebrated book of caricatures, Rossetti and His Circle (1922). Described by N. John Hall as Beerbohm’s ‘highest accomplishment in caricature’ (Max Beerbohm: A Kind of Life 149), this volume of 23 sophisticated designs is a far-reaching and highly amusing lampoon of Dante Rossetti, his associates and disciples, the art of the second stage of Pre-Raphaelitism in the 1850s, and the values of the Aesthetic 1860s; it even reaches as far as the Decadence and Oscar Wilde’s American tour in 1882.

Oscar Wilde preaching Aestheticism and the creed of Rossetti to the Americans. The affected Wilde is contrasted to the sceptical audience.

Of course, Beerbohm (born 1872) was not personally familiar with Rossetti or any of these figures or events but offers instead a comedic reconstruction which he based on written sources, biographies, reminiscences and a range of visual material. As he candidly explains in his prefatory note, his is purely a humorous re-imagining derived from ‘accounts of eyes witnesses’ along with ‘Old drawings and paintings [and] early photographs’ (vii). This material provided the source from which Beerbohm worked up his own satirical reading of the subjects, and within this general outline he focuses on three targets: the characters (whom he caricatures); their relationships (which become the subject of situational comedy); and the artwork (parody). In each domain he undermines pretension and rewrites the official hagiographies of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; in effect, he offers an alternative, absurdist history, a counterbalance to books by Holman Hunt, William Michael Rossetti and J.W. Mackail. Such volumes, Beerbohm sarcastically remarks, are ‘pleasant in tone’ and ‘prettily’ written (vii), but his aim is to bypass what he sees as the writers’ lack of objectivity as they viewed their subjects from an over-respectful perspective.

The artist’s focus, as registered in the title, is Dante Rossetti. Beerbohm regarded Rossetti as ‘one of the three most interesting men’ (6) of the nineteenth century – the others being Byron and Disraeli – and the painter-poet appears in 13 of the 23 designs. In each of these images the subject is depicted in line with Beerbohm’s belief that the ‘perfect caricature … must be [an] exaggeration of the whole creature … pose, gesture, expression,’ which in this case means that the Rossetti is depicted as overweight and languorous, dressed in an artist’s smock, and wearing a bohemian beard. These are presented as Rossetti’s ‘most salient’ features, which Beerbohm exaggerates into order to create what he considers to be the ‘epitome’ (Hall, Max Beerbohm Caricatures 15) of his character’s personality.

Dante’s porcine indolence is the object of special ridicule: his size is exaggerated and emphasized by dressing him in overlarge clothes and he is repeatedly shown lounging or leaning, unable to stand upright without support. Beerbohm typifies this approach in the plate showing Rossetti’s Courtship, in which he depicts his character with his elbow against the mantlepiece, his hands immobile with one in a pocket, and his legs crossed. He further endows his subject with heel-less slippers – a sign of slovenliness – and stresses his size, in a version of the fat and thin joke, by contrasting him with the figure of Elizabeth Siddal. Rossetti’s indolence is shown with even greater directness in the scene that places him on a chaise-longue, with Swinburne reading ‘Anactoria’ to his hero in the company of William Michael. In this design Rossetti is a vast figure, in the words of Henry McBride, ‘heavy and befuddled’ (207), with one arm dangling and his back propped up with a cushion; and in his encounter with Frederic Leighton all we see are his crossed legs and slippers.

Left: Beerbohm’s take on Rossetti’s courtship. Right: Swinburne reading to the Rossetti brothers.

Always inert, Rossetti the sage is presented as a sort of comic Buddha, ‘huge, untidy … and essentially unromantic’ (‘From Private Correspondence’ 9). The satire, one contemporary notes, is ‘merciless’ (‘Rossetti and His Circle,’ Birmingham 4), – and was intended to be. As McBride writes in The Dial in 1924, Beerbohm ‘whacks’ (206) the artist’s languor, which was supposed to be a key feature of Aesthetic artists. Beerbohm more generally deploys size, moreover, to indicate personality and status: Whistler is shown as a tiny, trivial figure when compared to the gigantic Carlyle ( Blue China, plate 8); Fanny Cornforth is huge, Ruskin is paper-thin; and Morris and Burne-Jones are figured as little and large in an image which crams the two into a Pre-Raphaelite settle, with Morris dominating the space just as he dominates the conversation.

Left: Whistler and Carlyle. Right: Morris overpowering a diminutive Burne-Jones

This physical caricature is matched by Beerbohm’s mockery of facial features and expressions, which are again taken as an indication of character. For example, he ridicules Rossetti’s alleged self-importance by endowing him with a morose expression in the manner of the stereotypical bohemian artist and thinker, and he suggests Morris’s restless personality, all activity and ideas, by exaggerating the inwardness of his looks while stressing the disorderliness of his hair and beard, as if his mental energy were struggling to be free.

Indeed, Beerbohm treats hair as a key indicator of personality. In the scene depicting Ford Madox Brown being patronised by Holman Hunt, Hunt’s red beard suggests his fiery dominance when compared to Brown’s fair appendage, and in the scene of Swinburne in the company of the Rossetti brothers the artist conveys Swinburne’s trivial nature by endowing him with wispy facial hair that contrasts with Dante’s artistic goatee and the biblical excess of William’s beard – a feature that further stands in amusing opposition to his egg-like baldness.

In each of these caricatures Beerbohm provides telling representations of his cast of Pre-Raphaelites as he understood them. At the same time, he develops the humour by framing his portraits within a series of comedic situations. The satirist primarily focuses on what might be called power-plays – with the competitive PRBs contending for dominance; the relationship between Topsy Morris and Burne-Jones exemplifies the situation, and so does the exchange between Holman Hunt and Burne-Jones. But Beerbohm repeatedly mocks Rossetti’s hegemony in the scenes showing him in the interviews with his acolytes: Swinburne is in awe of him, worshipping at his feet as he reads a poem as if it were a prayer, and the vast Rossetti dominates several other encounters (plates 12, 15, 18).

Bell Scott’s assessment of Rossetti’s disciples worshipping their god: an image that veers strangely towards the surreal.

Most amusing is the cartoon in which Beerbohm reveals the doubts that must have occurred to Rossetti’s friends. In William Bell Scott wondering, the artist imagines Bell Scott’s sceptical assessment of Rossetti’s charisma, showing his character looking at the absurdly rotund painter-poet leaning against a tree in his garden as he proclaims his aesthetic mantra to his disciples, with Swinburne again on his knees in homage and Morris and Burne-Jones listening on intently. This is a ridiculous interplay of ego and gullibility, and Beerbohm highlights Scott’s contempt for the situation by endowing him with a stern gaze and folded arms. However, the humour is mostly generated by the absurdist inclusion of animals from Rossetti’s private zoo at Cheyne Walk, with Morris holding hands with a wallaby and another cartoon animal – a wombat? – moving in the foreground. The effect is strange but the satirical point unambiguous: linking animals and artists, Beerbohm suggests that the latter are just as unknowingly stupid as the former, an analogy that connects Rossetti’s feeding of the minds of his followers to animals that need to be fed. The knowledge that Rossetti carelessly allowed his creatures to die of starvation informs the design and adds another layer of satire.

Once again, the mockery is a withering comment on Rossetti’s influence that reveals him as an emperor with no clothes, and Beerbohm is just as abrasive in his satirical attack on the artist’s other, more intimate relationships. In Rossetti’s Courtship he uses an image to suggest the true nature of Rossetti and Siddal’s marriage, which is not a matter of exquisite melancholy – as in Rossetti’s many drawings – but a matter of boredom and disorder, with the two participants standing listlessly in a bare room with an empty grate and scattered papers on the floor; a tiny mouse at the bottom left hand corner adds a final note of bohemian squalor. Though he does not represent anything ‘unseemly’ (Hall, Max Beerbohm: A Kind of Life 150) about Rossetti’s life, Beerbohm also stretches the notion of the artist’s respectability by showing the situation post-Siddal. In An Introduction he stresses Rossetti’s lack of decorum by showing a scene in which Ruskin meets Fanny Cornforth. Cornforth is represented as a voluptuous figure who physically intimidates the retiring critic, and the implication is that Rossetti is enjoying the impropriety of forcing the puritanical and (probably) impotent Ruskin to shake hands with his openly sensual mistress; as Hall remarks, the meeting is a knowing hit at ‘Ruskin’s undeveloped sexuality’ (Hall, A Kind of Life 150) and plays on his embarrassment.

A feeble Ruskin meets a flamboyant Cornforth; Rossetti slyly looks on.

In short, Beerbohm uses caricature and situational comedy to provide a wide-ranging lampoon of his subjects’ lives, values, relationships, and (most of all) their psychological and emotional limitations. Drawing in a ‘style slightly less distorting’ (Hall, A Kind of Life 149) than usual, the cartoonist is both penetrating and amusing.

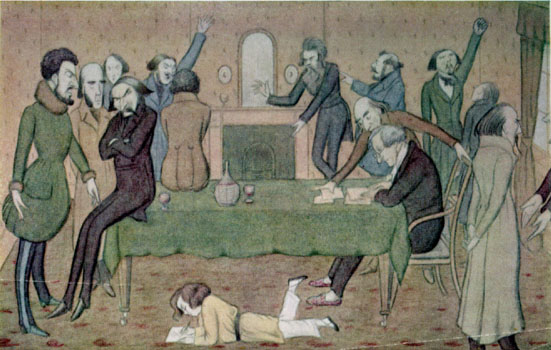

What, then, of the Pre-Raphaelites’ artwork? Focusing on parody, Beerbohm subjects the artists’ painting to the same sort of analysis as he applies to their figures. Rossetti’s early promise is registered in the pictorial frontispiece, which shows him as a child drawing in a sketchbook surrounded by his father’s gesturing revolutionaries as they debate the situation in Italy. The representation of the Italian radicals is amusing in itself, but the boy’s capacity to ignore the tumult is significant, satirizing the otherworldly remoteness, the indifference to the demands of the real world, that will eventually characterize his art. But Rossetti’s mature work is subject to far sterner analysis. Pastiche versions of the artist’s female portraits appear in the background of several of the designs, in each case rendered in caricature and displaying affected gestures (plates 13, 18, 20).

Rossetti’s juvenile dreaminess – as Italian expat radicals loudly argue politics at the fireside. The artist, who later declared he didn’t care if the Sun went round the Earth or the Earth around the Sun, is purely consumed by his imaginative inner world.

Equally amusing is Beerbohm’s take on the murals in the Oxford Union, showing Rossetti about to climb up a ladder to work on the outlined designs.

The image, as seen on the right here, is an accurate representation of the surviving painting, but the humour is generated by the incongruity of having an angular figure squeezed between two circular windows; as usual, the effect is absurd, and far from the mysterious results that Rossetti set out to achieve. The affectation of Pre-Raphaelite imagery, with its focus on angels and idealized beauties, is similarly mocked in Ned Jones and Topsy, which represents a pastiche version of a painted Arts and Crafts settle.

The image, as seen on the right here, is an accurate representation of the surviving painting, but the humour is generated by the incongruity of having an angular figure squeezed between two circular windows; as usual, the effect is absurd, and far from the mysterious results that Rossetti set out to achieve. The affectation of Pre-Raphaelite imagery, with its focus on angels and idealized beauties, is similarly mocked in Ned Jones and Topsy, which represents a pastiche version of a painted Arts and Crafts settle.

Beerbohm is at his harshest, however, in his satirical response to the art of Millais. In A momentary vision that once befell Young Millais he shows the artist in his first, Pre-Raphaelite stage recoiling from a vision of himself as the stout middle-aged painter, with one his later subjects sitting on his lap. The Pre-Raphaelite Millais recoils in horror as he contemplates the contrast between the radicalism of his youthful work – represented by the painting on his easel, Ferdinand Lured by Ariel (1850, Private Collection) – and the sentimental conventionality of his later work, denoted by the girl in Cherry Ripe (1879, Private Collection). Once again, the satire is both cruel and revealing.

Millais’s horrified contemplation of his change in style, with his early and later work contrasted.

Speaking more generally, Beerbohm’s series of cartoons is an effective hit at Rossetti and his circle, reducing the main character and his acolytes to the level of banality as he charts what he sees as their pretentions. The ultimate absurdity of the Pre-Raphaelites’ social circle and their art is summed up by Jowett’s question to Rossetti as he climbs the ladder in the Oxford Union: ‘And what are [the figures in the painting] going to do with Grail when they found it, Mr Rossetti?’(caption, plate 4). Beerbohm’s droll attack on the PRB makes us wonder if the brothers’ aims were just as chimeric and pointless.

Nevertheless, Beerbohm’s satirical montage is a rich mockery and comedic celebration of Pre-Raphaelite characters, values, and situations, and it is not surprising to find that it was a great success when it was published in the Modernist age as a backward glance at the Victorian past. One early reviewer calls it ‘an entirely delightful volume’ (Smyth 96), and for another it was an ‘outstanding’ book, the work of a ‘delectable’ (Holliday 290) artist. Viewed from the perspective of 2026, a century after the volume was issued, it is just as humorous as it was for the original audience of the 1920s.

Related Material

- Pre-Raphaelites, Associates and Later Followers

- Rossetti's Real Fair Ladies: Lizzie, Fanny and Jane

- Caricature (sitemap)

Bibliography

Beerbohm, Max. Rossetti and His Circle. London: Heinemann, 1922.

William E. Fredeman, ‘Pre-Raphaelites in Caricature: The Choice of Paris: An Idyll, by Florence Claxton.’ The Burlington Magazine 103, no. 663 (December 1960): 523.

‘From Private Correspondence.’ The Scotsman (14 September 1921): 9.

Hall, N. John. Max Beerbohm Caricatures. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Hall, N. John. Max Beerbohm: A Kind of Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Holliday, Robert Cortes. ‘A Short Course in Book Illustration.’ The Bookman. 57 (1923): 290.

McBride, Henry. ‘Max Beerbohm’s Rossetti.’ The Dial 74 (Jan–June 1924): 207.

‘Rossetti and His Circle.’ The Birmingham Daily Gazette (14 September 1921): 4.

Smyth, Clifford. ‘Rossetti and His Circle.’ The Literary Digest International Book Review 1 (1922): 96.

Created 12 January 2026