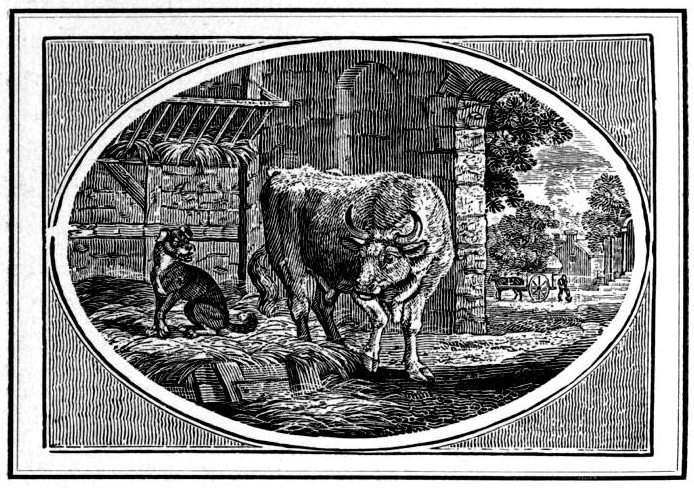

The history of nineteenth-century printing is intimately bound up with the engraved boxwood block, the single most significant piece of illustration technology, which dominated early Victorian book illustration. The first book to be so illustrated was Thomas Bewick's The General History of Quadrupeds (1790). The artist engraved his own white line illustrations on boxwood blocks, and the artist-engraver remained a common figure in book illustration until mid-century.

Two plates by Thomas Bewick from The Fables of Æsop. Left: The Dog in the Manger. The Cock and the Jewel. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Between 1850 and 1900, approximately 1,200 "art" books were produced in Britain. The decline in importance of the woodblock over those five decades as new technologies were introduced is evident: in the 1860s, only 6.5% of these books utilised two or more different methods of illustration, but by the 1890s this figure had risen to almost 30%. In the period 1850-1880, wood engravings accounted for 25% or better of all illustrations, with lithographs in second place (accounting for 27%, 20%, and 15% respectively over those three decades). The situation changed dramatically after 1881, a period in which wood engravings sharply declined and line illustrations became extremely popular, thanks in large measure to noted American book illustrator Joseph Pennell (1857-1926), who began his career in the United States, illustrating the works of George Washington Cable and William Dean Howells, but who in 1885 together with his wife, Elizabeth Robins, decided to work in London. Pennell was adept at producing pen and ink drawings that were easily transferred to wood photographically.

Two Styles of Woodblock Illustration

From mid-century, two styles of woodblock illustration occur, the 'old vignette' and the pen-and-ink drawing. In English Book Illustration 1800-1900 (1947), James defines the illustrated book as "a partnership between author and artist to which the artist contributes something which is a pictorial comment on the author's words or an interpretation of his meaning in another medium" (7). Often the artist was the first outside reader of the text and, in a sense, its first critic, as may be said of Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) in his artistic collaborations with Charles Dickens from the 1830s up to the end of the 1850s. The most celebrated wood-engravers were the brothers Dalziel (George, Edward, Margaret, and John), who founded Camden Press in 1857. George Dalziel worked on John Leech's first Punch illustration, and was frequently commissioned by the Illustrated London News. The Dalziels also produced the blocks for the Pre-Raphaelite-influenced Moxon Tennyson, which featured a total of fifty-five illustrations, thirty by Millais, Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and the remainder by such academic artists as Maclise and Landseer.

The Wood Engraver's Studio. Photographs by Jacqueline Banerjee, by courtesy of the Thomas Bewick Birthplace Museum and the National Trust, Cherryburn, Mickley, Northumberland. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Most woodblock illustrations appeared in the second half of the century, in periodicals published in London, which the 1872 Post Office Directory indicates was home to 128 wood-engraving firms. Among the outstanding woodblook series of the era are those by Gustav Doré for Douglas Jerrold's London: A Pilgrimage (1872), contrasting the lives of the affluent and the indigent, John Tenniel's highly imaginative illustrations for Lewis Carroll's Alice books (1865 and 1872), and those by Linley Sambourne for Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies (1863).

Electrotyping

The Voltaic Process, also known as electrotyping, which Thomas Spenser of Liverpool discovered in 1839, quickly replaced the various kinds of stereotyped woodcuts for the production of fine artwork in books. According to Spenser's Instructions for the Multiplication of Works of Art by Voltaic Electricity (1840), the engraved block could either be impressed into soft lead (which would serve as the cathode) or have a metallic face imposed upon before producing a mould and subsequently an electrotype. In the second half of the century, most woodblock engravings were actually printed from electrotypes of one kind or the other.

In The Art of Engraving (1841), T. H. Fielding describes two kinds of woodblocks. With the laid on style, the artist used India ink for the main tints and a pencil for the final details. In the less challenging facsimile style, the artist drew on the block every line that he intended his engraver to incise. Since the material used in both cases was boxwood, and the box is a tree with a trunk of small diameter, any illustration over five square inches in size had to be engraved on a composite block, that is, a block composed of two or more separate pieces of boxwood that had been glued together. Occasionally, in order to speed up the engraving process, several engravers would would on the same illustration at one time with each having a separate block; when finished, the four blocks would be screwed together. This was not an uncommon practice among illustrators of the pictorial journals and magazines of the 1860s.

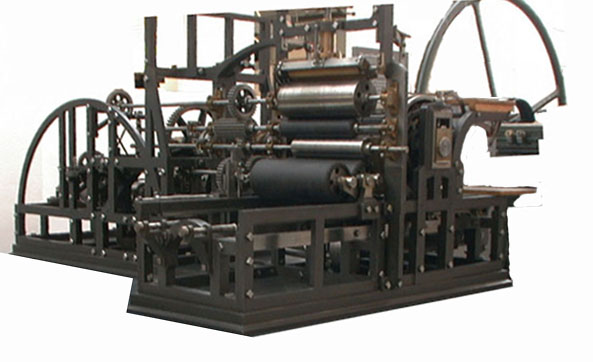

The Appearance of Cylinder Presses

Left: High-Speed Printing Press. Friedrich Gottlob Koenig and Andreas Friedrich Bauer. 1818. Right: Perkins D cylinder Printing Press. 1840. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Around mid-century, however, the presses used to produce books and periodicals changed, as hand presses were replaced by various cylinder presses, such as the power platen press manufactured Napier, Hopkinson, and Cope. These high-speed presses were far more efficient for longer runs, although certain art books were still produced in limited run on the hand press -- Moxon's celebrated edition of Tennyson in 1857 is an example. Later in the century, as photographic techniques replaced the woodblock, the art of wood engraving under the influence of William Morris's Arts and Crafts movement was once again practised by artists who were also engravers. Morris's Kelmscott Press, which he established in 1891, established a vogue for such high quality, limited production books produced in the manner of by-gone days.

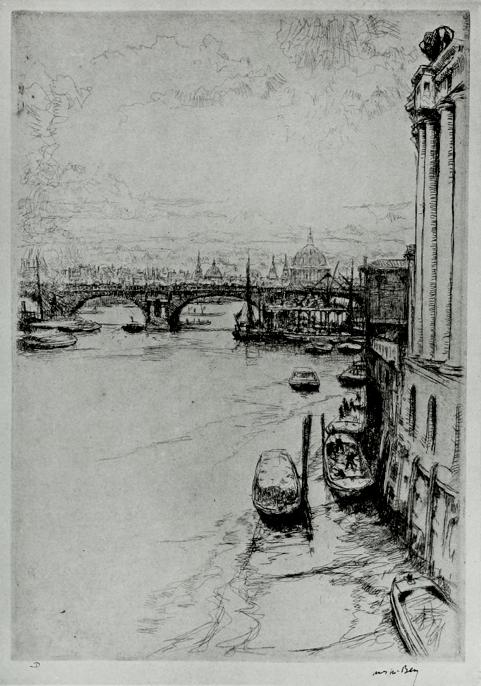

Etching

A very different pictorial technology co-existed with the woodblock, the etching. In this system of illustration, the surface of a copper (in the eighteenth century) or a steel plate was covered with a etching 'ground' designed to protect the plate's surface. The ground, a mixture of wax and pitch called asphaltum, was rubbed onto the heated plate's surface, which was then blackened by using a candle flame. With a lead pencil the workman would copy the picture on tracing paper, then place the tracing paper face down on the treated plate; he would then run paper and plate together through a rolling press to transfer the image from the paper to the plate's surface, which would present the desired image as a series of silvery lines against the black background. The engraver would work on the image with a series of steel needles with points of varying thickness, then immerse the plate in diluted nitric acid. About 1824, Edmund Turrell substituted a plate of steel, which he immersed in a corrosive mixture of nitric and pyroligneous acids and alcohol.

Left: The Lion Brewery, View from Charing Cross Bridge by James McBey. Middle: Billingsgate by J. M. Whistler. 1859. Right: Becquet (The Fiddler) by J. M. Whistler. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The most prominent Victorian illustrator to employ steel engravings was George Cruikshank, who provided such plates for Bentley's Miscellany from 1837 to 1843, and for The Ingoldsby Legends from 1840 to 1847. Whereas the copper plates used in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century book illustration would wear out after 4,000 good impressions, steel was much more durable.

Illustration in Color

Next we come to matter of coloured illustrations. According to Martin Hardie, "Hand-colouring, of course, increased the cost of the plates, and books containing them were generally from half as much again to twice the cost of uncoloured copies" (25). The mezzotint was produced on a plate of copper, or later steel, which would be deeply scratched with an instrument called a "cradle." The burrs on the plate would then be burnished or scraped away. Before the plate was grounded, the outline of the drawing was etched lightly, and then more deeply after all the tones had been put in place. As a result of the constant wiping of the plate's surface, a mezzotint plate wore so rapidly that only the early prints were suitable for book illustration. In 1820, William Say introduced the steel mezzotint plate, from which he was able to take 1,500 good impressions, although they lacked the rich tones which characterized images taken from copper mezzotint plate.

The aquatint involved an etched plate with a reticulated pattern; the image taken was then hand-coloured to simulate the effect of a water-colour painting. The process was introduced in the 1770s, but was little used after the 1830s.

John Leech's first book, Etchings and Sketchings, by A. Pen, Esqu. (1836), was published at two shillings "plain," but at three shillings "coloured." The price difference, as we have seen, is accounted for by the fact that "coloured" meant "hand-coloured," a time-consuming and therefore expensive process of applying water colours to printed images, whether etchings or engravings.

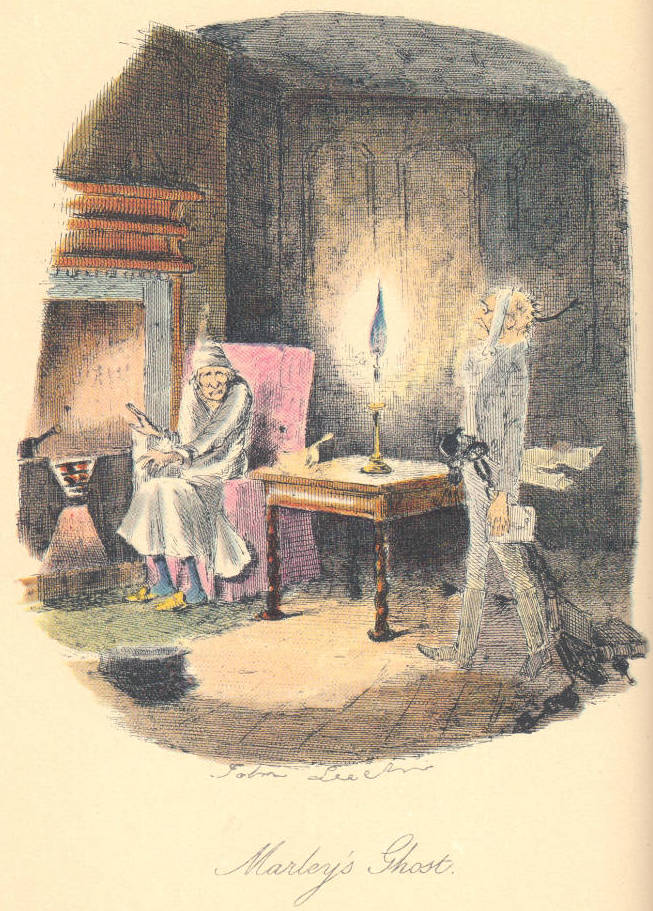

There is a long gap between Leech's first publication with plates coloured by hand, the Etchings and Sketchings of 1836, and his next venture in 1843, though in the meantime he had become the most successful artist-humourist of the day. In 1843 his services were secured by Charles Dickens to illustrate the Christmas Carol, the first and best of Dickens's Christmas Books, and the only one illustrated exclusively by Leech. The original issue was in brown cloth with gilt devices and edges, and bears as the heading to the first chapter, 'Stave I.' afterwards altered to 'Stave One' to harmonise with the other headings, which were always 'Stave Two,' 'Three,' 'Four,' and 'Five.' Moreover, in the first issue the end-papers are green, in the second they are yellow. In it there are four full-page etchings, beautifully tinted, and four wood-engravings drawn by the artist in his best manner. The first edition of the book (it reached a tenth edition by 1846) is valuable for the sake of both artist and author as well as for its rarity. It was followed by The Chimes in 1845 [sic], The Cricket on the Hearth and The Battle of Life in 1846, and The Haunted Man in 1848, all of them partly illustrated by Leech, but without any plates in colour. [Hardie, 209-10]

Marley's Ghost by John Leech. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

It is possible that the successors to A Christmas Carolwere not coloured because of the extra price that would have to be charged, and also because Bradbury and Evans had insufficient time before the publication date to have such work done. Whereas the Carol had only eight plates, the other Christmas Books contained many more--the last of the series, for example, The Haunted Man (1848), contained seventeen illustrations. As late as 1860, Leech's plates, as in Mr. Briggs and His Doings, were being hand-coloured.

Although many of Thackeray's plates were entirely hand-coloured, the fifteen plates in The Kickleburys on the Rhine (1851), engraved on wood, were finished with one colour already printed. Coloured lithography and colour-printing from woodblocks, innovations of the 1860s, helped to bring down the cost of books with colour illustrations. Another significant invention of the period was Alois Auer's "natural" printing process, in which an actual object such as a leaf was passed between plates of lead and copper through two tightly screwed rollers, leaving a textured impression of that object on the softer (lead) plate. Various colours could then be applied to the lead plate to obtain highly detailed and life-like images. An improvement in the process was stereotyping or galvanizing the soft lead plate in order to increase the plate's durability and therefore the number of impressions that might be taken. Auer patented his Naturselbstdruck method in 1852. Henry Bradbury (eldest son of William Bradbury of London's Bradbury and Evans, Dickens's publishers after 1843), who had become familiar with Auer's process while studying graphic arts in Vienna, introduced it into England in 1855, when his father's firm used it for the fifty-one colour plates in T. Moore and J. Lindley's folio The Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland.

Lithography

Two examples of lithography — left: The Great Eastern by Robert Dudley (1866). Right: The Grindstone, an illustration for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Harry Furniss. 1910 [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Lithography, cheaper and more versatile than nature printing, was invented by the small-time Czech printer and publisher Aloys Senefelder in 1798. By accident, he applied a ground composed of wax, soap, and lamp-black to a polished limestone surface, which he then bit with acid to produce an elevated image suitable for printing. Afterwards, he refined the process by using an ink composed of tallow, wax, soap, shellac, and Paris black to draw a picture on the polished stone surface before pouring an acid solution over the drawing to decompose the lime in the stone and the soap in the ink. "Before printing, the stone is well moistened with water, and when inked with the roller will receive the ink only on the greasy parts, that is the parts drawn upon, and will reject the ink from the parts treated with acid, gum, and water" (Hardie 235). Senefelder described his discovery in his Complete Course in Lithography (1818).

Left: The Kilsby Tunnel (Working Shaft) by J. C. Bourne (1839). Right: Ideal Pastoral Life by Edward Calvert. 1829 [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

By the end of the 1830s it was in common use, being employed in some very attractive books like John Britton's Drawings of the London and Birmingham Railway, 1839, with illustrations by John Cooke Bourne. It depends for its effect upon the antipathy between grease and water: a greasy image on a surface of smooth limestone is first moistened and then inked; the image repels the water but accepts the ink, while the stone accepts the water and consequently repels the ink. The image can then be printed on paper by passing stone and paper through a scraper press, which gives a picture in black on a white background. By 1837 it was becoming common practice to add the impression of another stone, printed in a straw colour to give a tinted background, and this produced what are known as tinted lithographs. In England they were developed by C. J. Hullmandel, who was the most important lithographer working in England in the earlier part of the century. [Wakeman 37]

Charles Joseph Hullmandel and J. D. Harding, the major watercolorist who was Ruskin's drawing teacher, continued to experiment with lithography; one method they tried involved overprinting the lithograph with a single yellow tint to bring out the highlights, patented as the "lithotint" in 1840. "The system now is to print one colour on each stone, or rather one tone, for the chromo-lithographer often builds up what may seem simple colours by the super-position of two or more tones. A saving, however, of time and expense may occasionally be effected by the same stone carrying two distinct colours on two separate parts" (Hardie 239). Some lithographs required more than twenty printings in various colours before they were finished. Once introduced to England in the early 1830s, lithography remained one of the most popular techniques for illustrating books to the end of the century, when photogravure displaced it.

Having spoken of the use for colour-printing in modern days of lithography, wood-blocks, and process, separately and in conjunction, it is right to add a reference to the rarer and more expensive method of colour photogravure. This is a way of printing photo-engravings in colours at one impression after the manner of the old mezzotints and stipple. Messrs. Boussod, Valadon et Cie. Have been particularly successful in their reproduction of water-colours by this method; and for its application to books one may mention the magnificent Goupil series of English Historical Memoirs (1893--), Skelton's Charles I., Holmes's Queen Victoria, etc. (Hardie 298).

Related material

References

Hardie, Martin. English Coloured Books. Intro. James Laver. (1909). Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1973.

Mitchell, Sally. "Wood Engraving." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. New York and London: Garland, 1988. P. 870.

Wakeman, Geoffrey. Victorian Book Illustration: The Technical Revolution. Detroit. Michigan: Gale Research, 1973.

Last modified 11 July 2017