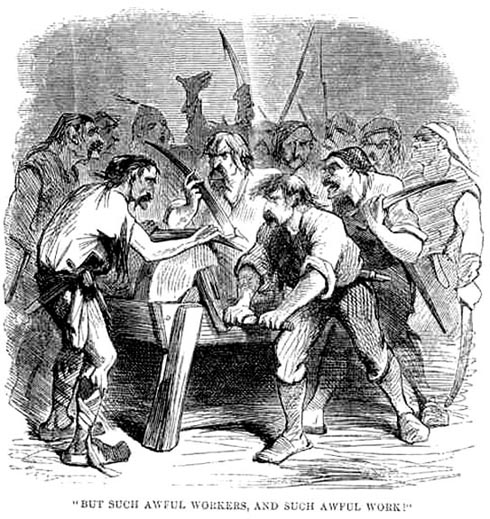

The Grindstone by Harry Furniss (1910), lithograph, 9.5 cm high x 14.6 cm framed. Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, The Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing XIII, 256. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: But, such awful workers, and such awful work!

The old man kissed her, and hurried her into his room, and turned the key; then, came hurrying back to the Doctor, and opened the window and partly opened the window and partly opened the blind, and put his hand upon the Doctor's arm, and looked out with him into the courtyard.

Looked out upon a throng of men and women: not enough in number, or near enough, to fill the courtyard: not more than forty or fifty in all. The people in possession of the house had let them in at the gate, and they had rushed in to work at the grindstone; it had evidently been set up there for their purpose, as in a convenient and retired spot.

But, such awful workers, and such awful work!

The grindstone had a double handle, and, turning at it madly were two men, whose faces, as their long hair flapped back when the whirlings of the grindstone brought their faces up, were more horrible and cruel than the visages of the wildest savages in their most barbarous disguise. False eyebrows and false moustaches were stuck upon them, and their hideous countenances were all bloody and sweaty, and all awry with bowling, and all staring and glaring with beastly excitement and want of slee As these ruffians turned and turned, their matted locks now flung forward over their eyes, now flung backward over their necks, some women held wine to their mouths that they might drink; and what with dropping blood, and what with dropping wine, and what with the stream of sparks struck out of the stone, all their wicked atmosphere seemed gore and fire. The eye could not detect one creature in the group free from the smear of blood. Shouldering one another to get next at the sharpening-stone, were men stripped to the waist, with the stain all over their limbs and bodies; men in all sorts of rags, with the stain upon those rags; men devilishly set off with spoils of women's lace and silk and ribbon, with the stain dyeing those trifles through and through. Hatchets, knives, bayonets, swords, all brought to be sharpened, were all red with it. Some of the hacked swords were tied to the wrists of those who carried them, with strips of linen and fragments of dress: ligatures various in kind, but all deep of the one colour. And as the frantic wielders of these weapons snatched them from the stream of sparks and tore away into the streets, the same red hue was red in their frenzied eyes; — eyes which any unbrutalised beholder would have given twenty years of life, to petrify with a well-directed gun. [Book Three, "The Track of a Storm," Chapter Two, "The Grindstone," 248-49: the picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary

The caption which J. A. Hammerton has provided does not immediately indicate the perspective from which the reader sees the mob sharpening its implements on the night of the third of September 1792, the actual date of the mass slaughter of aristocratic prisoners in the Abbaye, adjacent to the Abbey of St. Germaine, in the vicinity of which conveniently Dickens has located the Parisian branch of Tellson's Bank, a mansion in the midst of a previously aristocratic quarter on the left bank of the Seine. Dickens actually has his readers watch the savage mob from the window of Tellson's through the eyes of bank manager Jarvis Lorry (as opposed to the more biased view that Lucie or her father might provide). Rather than describe the horrific consequences of the blade-sharpening, Dickens reveals the horror of the September Massacres indirectly by focusing on the bits of feminine linen and lace, blood-stained, and the reddened grindstone, utilizing his background reading of Thomas Carlyle's description of this horrific slaughter in The French Revolution (3.1.4 and 3.1.5) and in particular his friend's recounting of the massacre of some eleven hundred prisoners over the course of 2 through 6 of September.

In contrast to Fred Barnard's crazed adult mob, stripped to the waist, Furniss's mob is fully clothed and contains a number of street boys in Phrygian caps, but no figures who are obviously women. Although the composition places the grindstone at the centre, Furniss presents most of the figures indistinctly in this lithograph of a pen-and-wash drawing. Whereas Barnard gives little indication of the setting, Furniss has situated the chaotic scene in a specifically urban context. Whereas Barnard's revellers consume bottles of wine as they sharpen knives and sabres, Furniss's boys in the foreground enthusiastically examine the sharpness of a sword and pike, while an ugly patriot races off right, presumably in the direction of the Abbaye.

In contrast to Hablot Knight Browne's avoidance of the sensational scene in the November issue, Barnard in the 1874 Household Edition wood-engraving The Grindstone, unlike Furniss in the present illustration, has moved in for the closeup, depicting with shocking intensity the manic Sans-culottes with wild hair, goggle eyes, and sharpened teeth. Thus, Furniss has subtracted some of the horror that readers of Harper's Weekly would have experienced in encountering the textual description simultaneously with McLenan's 1 October 1859 depiction of the weapon-sharpening crew of moustachioed thugs (modern-day Gauls) in But such awful workers, and such awful work!" (see below).

The presence of these juvenile Jacobins connects this scene of incipient mob violence on this side of the Channel with the tamer, less violent, and more high spirited pack of street boys who disrupt the spy's funeral by engaging in petty vandalism and unlawful congregation in Furniss's The Spy's Funeral, the bear-leader and his charge setting the tone for this amiable feast of misrule as in Furniss's model, Phiz's The Spy's Funeral from the September 1859 monthly number. Shortly, ominously testing the sharpness of the blades, these child-soldiers in the French scene will engage in the wanton slaughter of helpless and unarmed civilians as the Revolution, animated by the ideals of the Enlightenment, now deteriorates into lawless homicide on a grand scale. The text's emphasizing the blood on various pieces of trim from fashionable feminine attire clarifies precisely who these victims of mob violence have been, and again will be, as the revolutionary authorities apparently have done nothing to interevene.

Furniss's Six Other Darkened Lithographs for Historical Moments in the Novel

- 3. Stopping the Dover Coach, Book the First, "Recalled to Life," Chapter Two, "The Mail," facing 8.

- 21. The Fall of the Bastille, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Twenty-two, "Echoing Footsteps," facing 201.

- 22. The End of Foulon, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Twenty-two, "The Sea Still Rises," facing 217.

- 24. On the Way to Paris, Book the Third, "The Track of a Storm," Chapter One, "In Secret," facing 232.

- 26. The Carmagnole, Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 5, "The Wood-Sawyer," facing 265.

- 31. Sydney Carton and the little Seamstress, Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 13,"Fifty-Two," facing 337.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions: 1859, 1874, and 1905

Left: McLenan's 1 October 1859 depiction of the nightmarish street scene, "But such awful workers, and such awful work!" Right: Phiz's The Knock at the Door by in the sixth monthly number (November 1859).

Left: Barnard's Household Edition illustration depicting the frenzied mob outside the Paris branch of Tellson's in Book Three, Chapter Two, The Grindstone (1874). Right: Dixon's version of the mob arming itself outside Defarge's wine-shop in "Patriots and friends, we are ready" (1905). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974. IX (1859-61).

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Sanders, Andrew. A Companion to "A Tale of Two Cities." London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

Created 22 December 2013

Last modified 11 January 2020