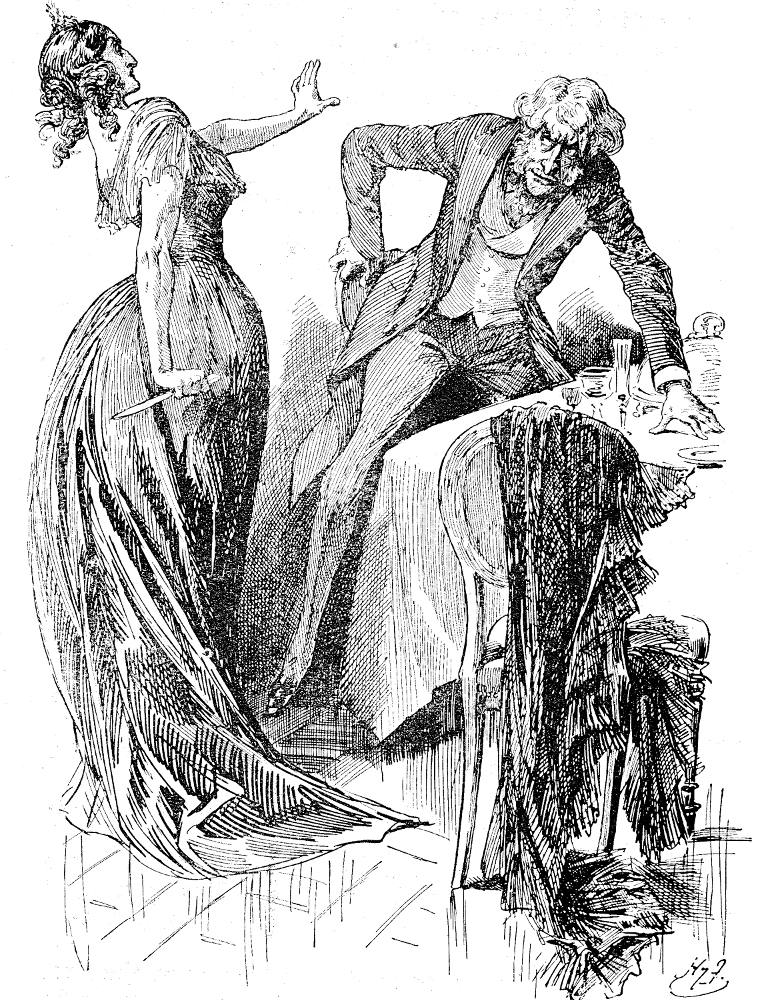

"Stand still!" she said, "or I shall murder you!" by W. L. Sheppard. Forty-sixth illustration for Dickens's Dombey and Son in the American Household Edition (1873), Chapter LIV, "More Intelligence," page 308. Page 307's Heading: "The Fugitives." 10.5 x 13.6 mm (4 ⅛ by 5 ¼ inches) framed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Edith rebels against Carker's domination

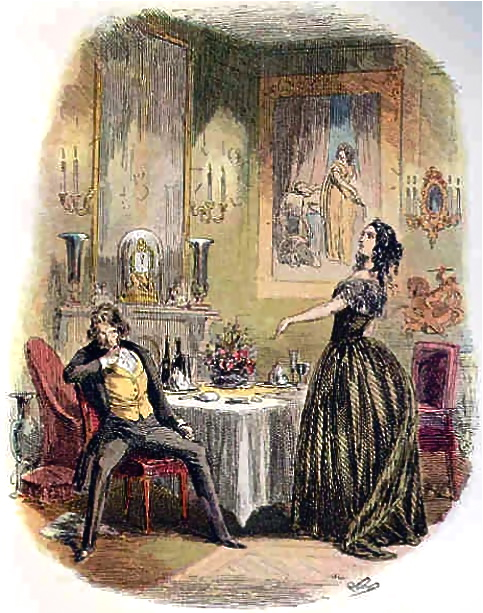

Harry Furniss's even more dramatic rendering of Edith's confronting Carker in France: Edith and Mr. Carker (1910).

Not a word. Not a look Her eyes completely hidden by their drooping lashes, but her head held up.

“Hard, unrelenting terms they were!” said Carker, with a smile, “but they are all fulfilled and passed, and make the present more delicious and more safe. Sicily shall be the place of our retreat. In the idlest and easiest part of the world, my soul, we’ll both seek compensation for old slavery.”

He was coming gaily towards her, when, in an instant, she caught the knife up from the table, and started one pace back.

“Stand still!” she said, “or I shall murder you!”

The sudden change in her, the towering fury and intense abhorrence sparkling in her eyes and lighting up her brow, made him stop as if a fire had stopped him.

“Stand still!” she said, “come no nearer me, upon your life!”

They both stood looking at each other. Rage and astonishment were in his face, but he controlled them, and said lightly,

“Come, come! Tush, we are alone, and out of everybody’s sight and hearing. Do you think to frighten me with these tricks of virtue?” [Chapter LIV, "The Fugitives," pp. 308-309]

Commentary: Nobody's Pawn

Phiz's almost operatic rendering of Edith's confronting Carker in the hotel-room: Mr. Carker in this Hour of Triumphr (1848).

After the hotel staff have laid the supper and left, Carker learns that Edith has not hired a new maid at Havre or Rouen, as he had instructed. But he still thinks he will have his way with her now they are alone. He hopes to put further distance between himself and the pursuing Dombey by continuing on to Sicily. However, when he approaches her at the dinner table, Edith grabs a knife and threatens him. She is planning to leave him, and certainly has no intention of becoming Carker's mistress. Edith had contrived the "elopement" simply to humiliate both Dombey and Carker, and as a pretext for escaping male domination. Although furious, Carker tries to manage Edith because he fears her.

Sheppard has based this boudoir scene late in the novel and set in Dijon, France, on Phiz's February 1848 serial illustration Mr. Carker in His Hour of Triumph. In the Sheppard revision, readers cannot accurately discern the expression on the manager's face, but he is certainly not smiling as he is the Phiz original, as befits the melodramatic villain of the novel. In neither Sheppard's nor Phiz's illustration does Carker present the same suave mask of self-assurance that he has worn heretofore. In this dramatic confrontation, Edith signals her rejection of his advances by a forceful pushing gesture. Her refusal of Carker's gallantry in this elegant furnished hotel apartment with dinner laid for two in Dijon sets up Carker's escaping back to England. There he will suffer a horrible fate: being crushed under the wheels of a locomotive as he runs from the authorities. In Sheppard's revision, Edith occupies the same position and is dressed in a fashionable dress similar to that in his earlier illustration, depicting the moment when Edith defied Mr. Dombey: From each arm she unclasped a diamond bracelet (Ch. XLVII).

An air of splendour, sufficiently faded to be melancholy, and sufficiently dazzling to clog and embarrass the details of life with a show of state, reigned in these rooms The walls and ceilings were gilded and painted; the floors were waxed and polished; crimson drapery hung in festoons from window, door, and mirror; and candelabra. . . . [306]

Since Dickens has taken considerable pains to set the scene at the French hotel, and since had realised the impression of opulence, slightly faded, in the drawing-room scene, one would expect that Sheppard would convey a similar impression by realising some of the above details. Instead, Sheppard introduces paintings, heavy furnishings, and figurines. A significant background detail apparently invented by Sheppard is the oil-painting behind Edith. In it, a woman appears to be throttling a sailor by ringing his neck. The Elizabethan figurines flanking Carker suggest his pose of gallant protector of Edith, but clearly she sees through his pretentions as a fellow "slave" who will provide her with safe haven. Magnificent in her defiance, Edith concludes by dismissing him: "Wretch! We meet tonight, and part tonight. For not one moment after I have ceased to speak, will I stay here!” (310).

Comment: on the Inset Paintings in the Sheppard and Phiz illustrations for Ch. LV

Sheppard's ambiguous inset painting of a woman perhaps throttling a sailor to imply Edith's vengeful and menacing attitude in "Stand still!" she said, "or I shall murder you!" (1873).

Joseph Kestner suggests that such terrifying and emasculating female figures as the ambiguous murderess in Sheppard's inset may be interpreted as "typifying the social conscience, sentimentality, and anxiety of the period" (95). Whereas previous depictions of women emphasized the female as a victim of male exploitation (e. g., John Everett Millais, The Order of Release, 1746, exhibited 1853; G. R. Redgrave, The Sempstress, 1844, and William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience, 1853), by the late 1840s, artists employed more specialised images, such as the nun and the sorceress, as, for example, Charles Allston Collins' Convent Thoughts (1851) and Millais' The Vale of Rest (1858). THe inset painting anticipates this new ambiguity about the female seen in Frederick Sandys' somewhat masculine Vivien (1863). The actual inset may depict a mother and child, or a woman throttling a man. "If some of these images represent concern for the condition of women, others embody fears that were expressed socially, for example, in the Contagious Diseases Acts of the 1860s or the exclusion of women from higher education. Graham Hough comments in The Last Romantics that these cultural phenomena were evident from mid-century . . ." (Kestner 95). Thus, although Sheppard in his ambiguous inset painting may be responding to the inset painting of Caravaggio's Judith and Holofernes (c. 1598-99) in Phiz's illustration, he was likely also responding to these more recent conceptions of the dangerous female, whom both Edith Dombey and Alice Marwood in the 1846-48 novel prefigure.

Related Material, including Other Illustrated Editions of Dombey and Son (1846-1910)

- Hablot Knight Browne's 40 original serial steel engravings for the serial (October, 1846, through April, 1848)

- Dombey and Son (homepage)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1862)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1862)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1862)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 61 Illustrations for the British Household Edition (1877)

- The Harper and Brothers & Chapman and Hall Household Editions

- Harold Copping's seven illustrations for Mary Angela Dickens's Children's Stories from Dickens (1893)

- W. H. Ç. Groome's illustrations of the Collins Pocket Edition of Dombey and Son (1900, rpt. 1934)

- Kyd's five Player's Cigarette Card watercolours (1910)

- Harry Furniss's 29 illustrations for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by W. L. Sheppard. The Household Edition. 18 vols. New York: Harper & Co., 1873.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1862. Vols. 1-4.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr., and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. III.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Fred Barnard [62 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877. XV.

__________. Dombey and Son. With illustrations by H. K. Browne. The illustrated library Edition. 2 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, c. 1880. II.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. 61 wood-engravings. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877. XV.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by W. H. C. Groome. London and Glasgow, 1900, rpt. 1934. 2 vols. in one.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. IX.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ("Phiz"). 8 coloured plates. London and Edinburgh: Caxton and Ballantyne, Hanson, 1910.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ("Phiz"). The Clarendon Edition, ed. Alan Horsman. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974.

Kestner, Joseph. “Edward Burne-Jones and Nineteenth-Century Fear of Women.” Biography, vol. 7, no. 2, University of Hawai’i Press, 1984, pp. 95–122, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23539153.

Created 26 February 2022