Poynter as an Illustrator

Edward Poynter was primarily a neo-classical painter who represented an imaginary notion of the ancient world. Christopher Wood places him among the ‘Olympian dreamers’, and his imagery is closely linked to the quasi-historical fantasies of Frederic Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Hugely successful as a figure of the art establishment and one time President of the Royal Academy, Poynter’s modern reputation as a painter has been eclipsed by the work of his more accessible contemporaries, with few studies examining his works on canvas. On the other hand, his value has an illustrator has been the subject of a modest revival in interest, with Goldman (pp. 210–211; pp. 305–306) and Suriano (pp.176–85) providing astute accounts of his contribution to the graphic art of the 1860s.

Poynter’s illustrations are in many ways difficult to judge. He contributed a small number of images to the Churchman’s Family Magazine, London Society and Once a Week, as well as publishing a single design in Jean Ingelow’s Poems of 1867. The tone of some of these engravings is uncertain and several were produced to satisfy the insatiable demands of the periodical press, the work of economic necessity rather than inspiration.

Left: A Dream of Love. Right: I can’t thmoke a pipe. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

However, his best designs are undoubtedly ‘interesting and inventive’ (Goldman, p.210). Most successful are those which replicate the imagery of his paintings; never trained as an illustrator, and entirely self-taught as a ‘draughtsman on wood’, Poynter’s work in black and white is validated by its painterly composition, attention to detail and figure drawing. It is well-known that book illustration of the sixties recreates the academic standards of contemporary fine art, and Poynter typifies those who approached his graphic designs as miniaturized versions of his paintings, and requiring the same amount of toil. As Suriano comments, he ‘saw little difference between the effort exerted for a monumental painting and for a small wood-block drawing’ (p.178). This is a telling comment: though Goldman views him as a sensitive illustrator with a sympathetic ‘perception’ of the text. (p.211), his approach, I suggest, is primarily pictorial rather than literary. In my view he treats his subjects purely as a starting point for his composition and is always concerned with the creating of aesthetic effect rather than the opportunity to help the reader to interpret the letterpress; autonomous designs in their own right, they reinforce the prejudice that artists of the period were poor illustrators but outstanding draughtsmen, painters who practised in colour on canvas and in the limited palette of black and white on the printed page.

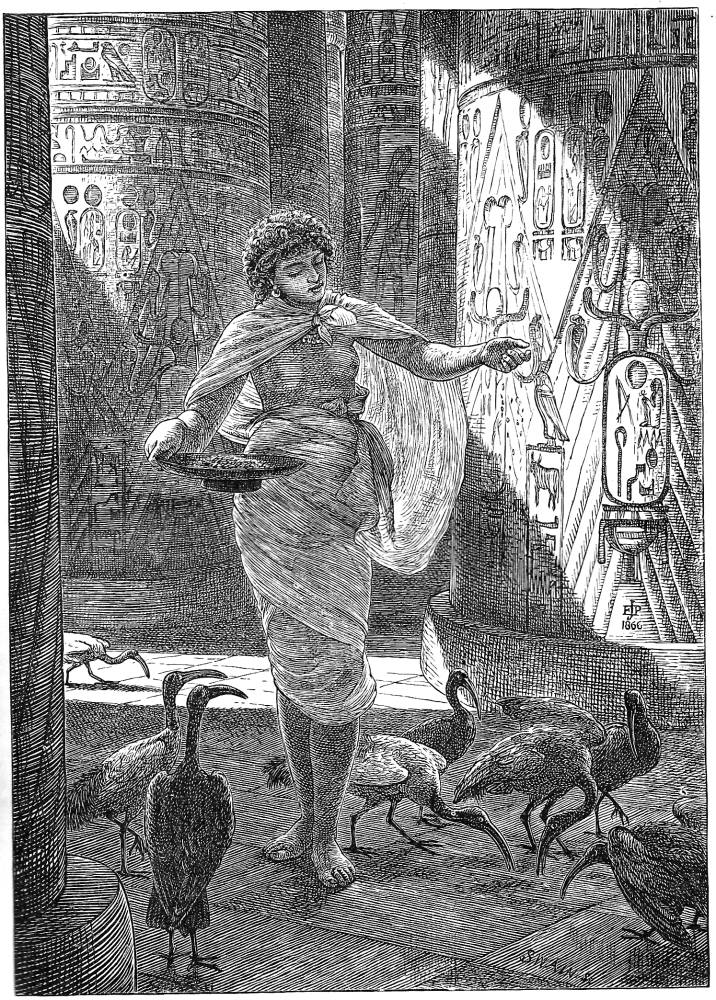

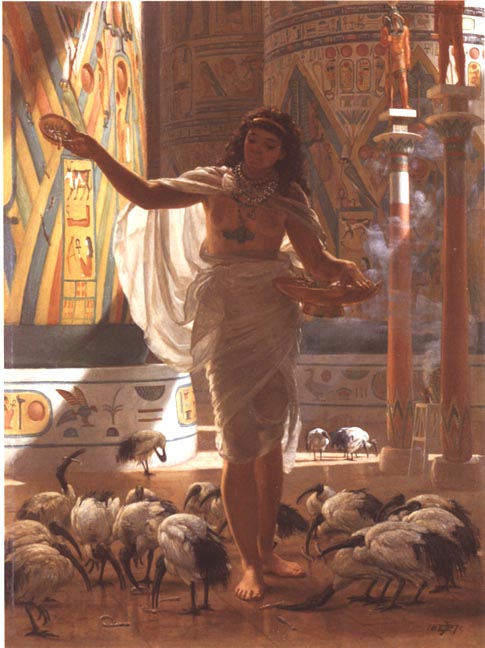

The relationship between the two types of art is symbiotic. There are several occasions where Poynter uses the same design interchangeably – an approach also found in the art of Simeon Solomon, J.E. Millais and Fred Walker. A good example is Feeding the Sacred Ibis in the Halls of Karnac. This appeared in the form of a wood-engraving in Once a Week in 1867 (n.s. 3: facing p. 238) and reversed, with minor alterations to the background and the arrangement of the figure, as a painting of 1871. Poynter monopolized on his strongest designs, and these appear in variant forms in austere black and white and luscious colour.

Feeding the Sacred Ibis in the Halls of Karnac — two versions of a similar subject in wwod-engraving (left) and oil on canvas (right). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Economical at least insofar as it allowed the artist to capitalize on his portfolio, this approach is both a strength and a weakness. He found the perfect accommodation of his strategy in the work for the Dalziels’ illustrated Bible, which was published in the eighties as the Bible Gallery.

Poynter and the Dalziels’ Bible Gallery

Poynter contributed twelve designs to the Brothers’ pictorial telling of the Old Testament and all were used; only Solomon completed more (20), although only six were published in 1880 (the remainder appeared in 1894). Poynter was commissioned in 1862, but production only continued in the intervals between the artist’s other tasks and was constantly delayed by interruptions and procrastination; like many of his fellow contributors he responded to his commission with anything but professionalism, and his dealings with the Dalziels dragged on, with no result, for more than a decade. Writing on November 1865, more than two years after he was engaged, he wrote to the engravers pondering five subjects; none was completed. He also mentions one of the ‘Joseph’ drawings, which he did present, although even then he makes an excuse for somehow not sending it on time, mentioning an absurd mix-up with a servant and blaming the delay on being ‘out of town’ (Dalziels, Record, p. 248). The situation did not change, and in November 1871 he writes commenting on the proof of one of the engravings, which he finds ‘rather spotty’ and lacking ‘breadth of light’ (p.250). Alterations were made, but Poynter’s exactitude was just another example of his incapacity to bring the project to a close. He thanks the Dalziels for their patience, hoping he is ‘not giving [them] too much trouble!’ (p.250); but there can be little doubt that his time-wasting – which was rivalled only by the tardiness of Richard Doyle (pp. 62–5) – was more than a minor irritation.

Of course, the Dalziels were treated like this by most of the artists working on their illustrated Bible. Sandys, Leighton, Watts and Holman Hunt were all as unreliable as Poynter and it was not until 1880 that the work appeared in the form of the Bible Gallery, which was a critical and financial flop. Begun, the Brothers lament, ‘with the highest aims’ and a ‘dead failure’ in the financial sense of the term, with only 200 copies being sold, it was a poor return for many years of ‘patient labour’ (p.256). Yet none would regard Poynter’s contributions to the Gallery as anything but a great success. Goldman describes the work as distinguished (p.211) and Reid, otherwise dismissive of Poynter’s illustrations, astutely comments that the book ‘gave him the opportunity to do the kind of thing he could do best’ (p.96). Reid does not elaborate, but it is clear that the Dalziels’ publication enabled him to exploit key aspects of his style as a neo-classical and historical painter.

Poynter’s principal strength as a Biblical illustrator was his mastery of a type of imaginative antiquarianism. This seems like an oxymoron but, like many neo-classicists, he was distinguished by his ability to materialize imagined scenes in a visual language that recreates the physicality of the lost civilizations of Rome, Egypt, Byzantium and Greece, creating what might have been while loosely observing – and sometimes wilfully distorting – the known facts. Appearing, in those loaded terms of the mid-nineteenth century, to be ‘real’ and ‘truthful’, his paintings give the semblance of journalistic exactitude which is put at the service of the dramatic and imaginative. By turns anachronistic and scholarly, notably in their pedantic recreation of hairstyles that are obviously of the painter’s own time, his images map a distinct sense of how the classical age should appear, presenting a backward glance which embodies ‘modern’ desires. This capacity to evoke the ancient world was put to good use in visualizing Biblical costumes, ornament and architecture.

In his work for the Bible Gallery, Poynter validates the scriptures’ settings by presenting them in vivid images which recreate the vast buildings of the Pharaoh’s Egypt. He traces Joseph’s narrative in four of his illustrations and in each of these he stresses epic scale and intricate decoration, presenting the past as a series of architectural spaces. In Joseph before Pharaoh the figures are placed within a colossal atrium; brutalist piers define the background and other structures can be glimpsed in the cityscape outside.

Left: Joseph Before Pharaoh. Right: The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Though fanciful, the effect is one of plausibility, exploiting a lexicon and epic scale which are shared with his works on canvas. There is a familial relationship, for instance, between the architecture and ornament in Joseph before Pharaoh (1864) and the elaborate scene in The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon (1890, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Australia). Moses and Aaron before the Pharoah and Joseph Presents his Father to the Pharaohare similarly figured as if they were huge paintings in black and white. All of the illustrations can be linked to the monumental Israel in Egypt (1867, Private Collection), and if coloured could easily be mistaken for oils. It is quite likely the book was broken up by many of the early purchasers and broken up into prints and framed, so making the differences in scale irrelevant; indeed, this activity was encouraged by the Dalziels, who issued one imprint of the book in the form of a portfolio of single sheets, ready for the frame, and ready to be placed over the mantelpiece.

Israel in Eygpt [Click on image to enlarge it.]

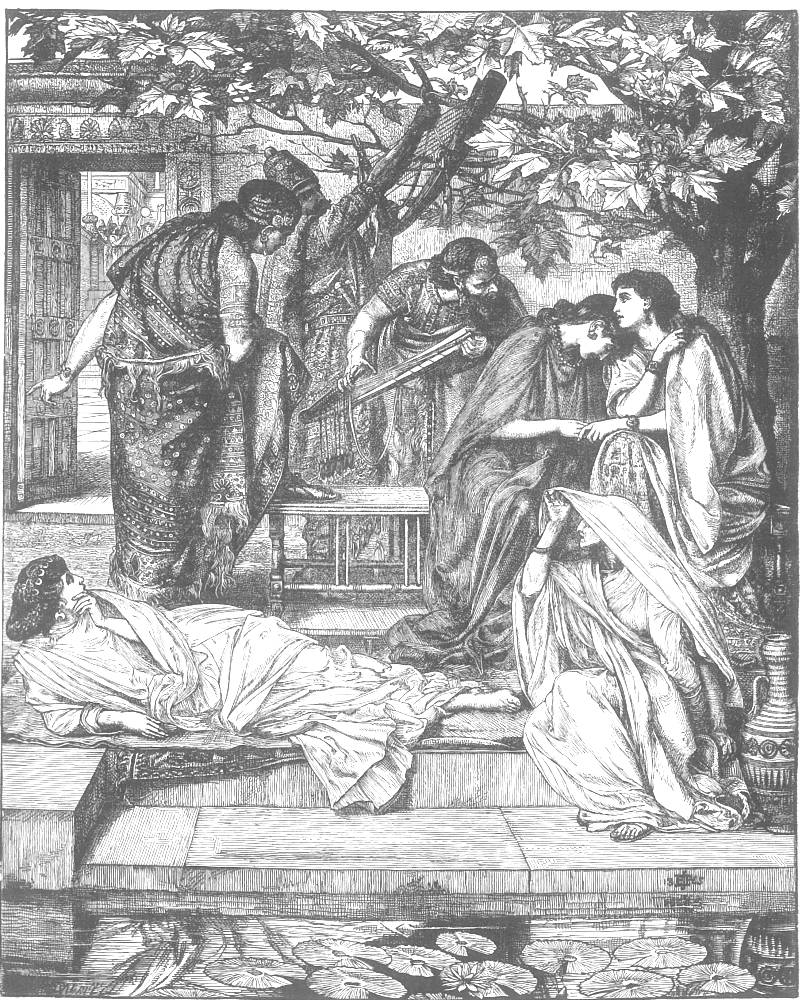

The implied scale of Poynter’s scenes acts as a means of representing the scriptures’ heroic values. Yet Poynter also excelled at representing closed, domestic spaces. Daniel’s Prayer plausibly re-imagines the character’s private rooms, complete with elaborate ornamentation and intimate spaces. The same is true of Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh, which articulates its tableau of figures within an elaborate series of perspectival recessions, each defined in parallel lines which bisect the surface with geometrical exactitude. The effect recalls the spatial schemes of Dante Rossetti’s watercolours, and recreates the sense of endless recession that characterizes Pre-Raphaelite painting and illustration.Poynter’s manipulation of Pre-Raphaelite space is matched by his emphasis on detail. As noted earlier, he presents his illustrations as if he were reporting a real event, and there are several occasions where the particularization of objects, costumes and spaces is taken to an absolute extreme. Though Goldman describes him as a ‘high Victorian’ (p. 210), Suriano views him as a Pre-Raphaelite in the specific sense of drawing his illustrations in a style that is ‘insanely Pre-Raphaelite [in its] accumulation of … decorative/architectural details, in filling every millimetre of the picture [in the manner] of what Holman Hunt did in most of his paintings’ (p.178). Poynter’s illustrations are the most detailed of the Gallery designs, and in some of the images the cataloguing of objects is indeed obsessional. In Pharaoh Honours Joseph and Joseph Before Pharaoh we are presented with details of decorative carpets, jewellery, carved ornamental capitals and patterns on the costumes: all are described minutely, and it is also possible, in the manner of Hunt, to distinguish between the textures of surfaces. This registration of the phenomenal world is finely realized in Pharaoh Honours Joseph (which contrasts Joseph’s costume with the burnished floor and the Pharaoh’s leopard-skin cloak), and again in By the Rivers of Babylon. In this design we have a series of contrasts, notably between the water-lilies and the marble floor and between the leaves, which appear, anachronistically, to be those of a northern European sycamore, and the limpid water. The rushing water in Moses Strikes the Rockand the animals’ coats in Moses Keeping Jethro’s Sheepare likewise figured as explorations in the representation of touch and texture.

Left: Pharaoh Honours Joseph. Middle: Moses Keeping Jethro’s Sheep. Right: Moses Strikes the Rock. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Poynter’s deployment of Pre-Raphaelite detail links his art to other contributors to the Bible Gallery, particularly Sandys and Solomon. Poynter’s cataloguing of the natural world as it is shown in By the Rivers of Babylon forms an interesting comparison with the treatment of nature in Solomon’s Abraham and Isaac, and the linkage between the two artists helps to unify what is otherwise a disparate collection. Poynter is further connected to Solomon insofar as he too is an artist who mediates between the extreme exactitude of Pre-Raphaelite detail and the abstractions of neo-classicism. Solomon moves between nature and languid, poetic reveries in which he contemplates Beauty, and this is equally true of several of Poynter’s designs.

Left: By the Rivers of Babylon. Right: Abraham and Isaac. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Though a Pre-Raphaelite portrait of a real world, By the Rivers of Babylon also reads as a typical piece of neo-classical languor in which the emphasis is on the private lives of idealized women, types of beauty who exist in what is almost, if not quite, a place without a narrative. Though representing a specific event, it prefigures paintings such as At the Corner of the Market Place (1887) while resembling the Arcadian and Roman fantasies of Albert Moore and L. Alma-Tadema. Like these pictures, Rivers of Babylon envisages a poetic atmosphere rather than a tale.

This emphasis on aesthetics rather than narrative is developed in other illustrations for the Gallery, and there are several occasions when Poynter seems to have been entirely unaware of his role as an interpreter of a literary text. Though nominally depicting a moment, some of his finest designs are meditations on Beauty, with little consideration of the scene’s wider significance. These images combine Pre-Raphaelitism and neo-classicism, but in all such cases there is strong tendency towards abstraction, focusing our attention on the picture’s pattern and rhythm in the manner of James Whistler’s ‘symphonies’ of the sixties. This process of mediation, which moves between realism and abstraction, is signalled in Pharaoh Honours Joseph: though depicting a moment of some import, the composition as a whole is figured as an arrangement of rhythmic arabesques and recurring shapes in which the overall impression is one of flatness in the manner of decoration, rather than a dramatic scene. As Reid explains, it is ‘frankly a decorative pattern’ (p.96). The delicacy of Poynter’s design is taken further in Miriam. The illustration depicts Miriam and the women singing songs and dancing in praise of the Lord, but the action is less important than the subtle articulation of the sinuous lines that flow through the robes and arms and animate the design’s surface, a technique Poynter also uses in the image of Persephone in Jean Ingelow’s Poems (1867), and in the painting of Andromeda (1869). The emphasis on abstraction is taken to its conclusion in The Israelites in Egypt: Water-Carriers; representing what is only a small detail in the narrative, the image presents an abstracted version of beauty in which the women, vases and background are conceived as shapes within a series of patterns.

Left: Miriam. Middle: Persephone. Right: Andromeda. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Poynter’s work for the Bible Gallery might thus be described as a complex and ambitious. Conceived as miniature epic paintings in black and white, they mirror the imagery of his works on canvas while also linking to the wider debates surrounding Pre-Raphaelitism and Aesthetic neo-classicism. Superior to the work by Leighton and Watts, their sustained visualization of the scriptures, as the site of Beauty and Truth, is only matched by the series created by Simeon Solomon.

Works Cited and Sources of Information

Art Pictures from the Old Testament and Our Lord’s Parables. With letterpress by Alex Foley. London: Dalton, n.d. [1921].

Brothers Dalziel, The. A Record of Work 1840–1890. 1901; rpt. London: Batsford, 1978.

Cooke, Simon. ‘Notable Books: The Dalziels’ Bible Gallery’. The Private Library 5th Series, 10:2 (Summer 2007): 59–85.

Dalziel’s Bible Gallery. London: Routledge, 1881 [1880].

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration: The Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996, 2004.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties. 1928; reprint, New York: Dover, 1975.

Suriano, Gregory R. The Pre-Raphaelite Illustrators. Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2000.

Wood, Christopher. Olympian Dreamers. London: Constable, 1983.

Created 31 July 2015