eorge du Maurier (1834-1896), illustrator and novelist, and grandfather of novelist Daphne du Maurier, was born George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier in Paris. He was brought up with the notion that his aristocratic grandparents had fled France during the Revolution, leaving vast estates behind to live in England as émigrés.

The truth, however, is that George's grandfather, Robert Mathurin, a glass-blower by trade and a speculator by inclination, left France in 1789 to avoid fraud charges. To bolster his aristocratic image he added "du Maurier" to his name. Initially, he worked for the Whitefriar's Glass Company in London, but his confidence schemes soon landed him in prison. By 1802, he had six children, but returned to France to escape his domestic responsibilities, and worked until his death in 1811 as a schoolmaster. His fourth son and du Maurier's father, Louis, born in 1797, grew up in London, but when he was eighteen his mother moved the family back to Paris so Louis could study opera. Taking up inventing instead, in 1831 Louis married Ellen, daughter of a notorious regency courtesan, Mary-Anne Clarke.

eorge du Maurier (1834-1896), illustrator and novelist, and grandfather of novelist Daphne du Maurier, was born George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier in Paris. He was brought up with the notion that his aristocratic grandparents had fled France during the Revolution, leaving vast estates behind to live in England as émigrés.

The truth, however, is that George's grandfather, Robert Mathurin, a glass-blower by trade and a speculator by inclination, left France in 1789 to avoid fraud charges. To bolster his aristocratic image he added "du Maurier" to his name. Initially, he worked for the Whitefriar's Glass Company in London, but his confidence schemes soon landed him in prison. By 1802, he had six children, but returned to France to escape his domestic responsibilities, and worked until his death in 1811 as a schoolmaster. His fourth son and du Maurier's father, Louis, born in 1797, grew up in London, but when he was eighteen his mother moved the family back to Paris so Louis could study opera. Taking up inventing instead, in 1831 Louis married Ellen, daughter of a notorious regency courtesan, Mary-Anne Clarke.

George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier, born in Paris on the 6th of March, 1834, was raised on the myth that his family's lineage could be traced back to the 12th century. The grandchild of a Frenchman who had fled to England and the son of an Englishwoman exiled by society to France, George learned English and French simultaneously--it is no accident, then, that his novels embody the motif of split-personality. Soon after George's birth, his family moved to Brussels, where Louis became scientific advisor to the Portuguese embassy. To enable Louis to continue his scientific studies (which never amounted to much in terms of financial success), the du Mauriers returned to Paris, living in various houses and apartments in the tranquil suburb of Passy between 1842 and 1846. From his schoolroom window at the Pension Froussard, George must have watched in awe as street fighting ushered in the 1848 revolution that deposed the "Citizen-Monarch," Louis Philippe. In 1851, having failed his Latin paper, George du Maurier did not graduate, but his father quickly arranged for his son to complete his education by studying chemistry at the Berbeck Chemical Laboratory, University College, London. At the age of seventeen, George du Maurier, accompanied by his entire family, settled into a Pentonville apartment.

“Depressed, he lost himself in the National Gallery, Covent Garden, and the British Museum.” Left to Right: the National Gallery, Covent Garden, and the British Museum.

Quickly giving up on chemistry, George temporarily aspired to be an opera-singer, just as his father had, but his voiced proved inadequate. Depressed, he lost himself in the National Gallery, Covent Garden, and the British Museum. In 1853 his sister Isabella introduced him to the beautiful heiress Emma Wightwick, who was to become his wife a decade later. In 1856, shortly after his father's funeral, George was off again, this time to study art in Paris; again, the entire family accompanied him. While attending the atelier of painter Charles Gleyre, he became friends with such talented young artists as the American painter James Whistler, Thomas Armstrong (later, Director of Art at the South Kensington Museum), and Edward Poynter (later, President of the Royal Academy). He continued his artistic studies in Antwerp, Malines, and Düsseldorf, returning to London in 1860 to seek employment as a magazine illustrator. In the fall, Once A Week agreed to publish his illustrations for the story "Faristan and Fatima," and then Mark Lemon agreed to publish his first cartoon for Punch.

In 1861, beginning to make a name for himself as a cartoonist and receiving constant commissions from Once A Week, George du Maurier proposed to Emma Wightwick, and, despite his mother's objections, married Emma on the 3rd of January, 1863. Within two years, he was appointed to the staff of Punch, and remained a cartoonist and illustrator there until his death.

A page from A Legend of Camelot and two details from other pages.

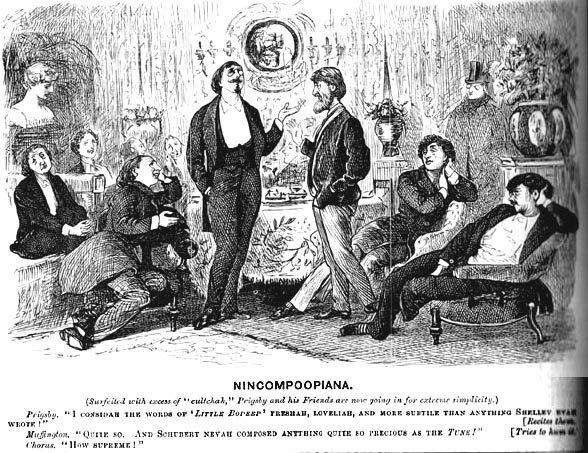

In 1866, he submitted his first major work for the magazine, a series entitled "A Legend of Camelot" that satirized the aesthetic movement's leading figures (Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Charles Baudelaire, and Walter Pater in particular) and their "Cult of Beauty." Up until 1885, he continued this satiric assault by creating such memorable figures as Mrs. Cimabue Brown (a Philistine), Jellaby Postwaite (a poet), Maudle (based on Oscar Wilde), Prigsby (a sycophant), Grigsby (an ordinary chap trying to emulate the aesthetic movement's fashions), and those exquisite parodies of the nouveaux riches and patrons of the arts, Mrs. Ponsonby de Tomkyns and Sir Gorgius Midas.

Three cartoons satriizing the Aesthetic Movement. Left to Right: An Infelicitious Question; Nincompoopiana; and Perils of Æsthetic Culture

In 1869, du Maurier and his wife moved to the Bohemian community on London's Hampstead Heath. Neighbours at Frognall included noted fairy and child artist Kate Greenaway (a link between du Maurier and Ruskin) and Sir Walter Besant, the novelist, a friend since their days together at Cambridge (1855). The du Mauriers' annual summer vacations at such French seaside resorts as Dieppe, Le Havre, and Étretat, as well as the social and artistic life of their little village, are often reflected in du Maurier's Punch cartoons -- a special favourite of readers was the lovable family pet Chang, a St. Bernard; like du Maurier himself, the readership was stricken when the great dog died in 1883. In 1874, now aged forty, du Maurier moved his family into New Grove House, Hampstead, which would be their home for the next twenty years. Although the artist friends of his youth no longer called, he often exchanged visits with Pre-Raphaelite artist John Millais, the best-selling novelist George Eliot, and her partner, G. Henry Lewes, editor of the prestigious Westminster Review. During the early 1870s, du Maurier began to suffer eye problems, for which his doctor recommended working on a larger scale. As a result, Du Maurier's work declined in quality.

Walter Besant persuaded du Maurier to join the celebrated Rabelais Club, founded in 1879, which held literary dinners once every two months. Other high-profile members included novelists Henry James, Thomas Hardy, Bret Harte, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, and artists Lawrence Alma Tadema and John Millais. Between 1881 and the club's demise in 1889, three volumes of the club's literary proceedings appeared. Among the members' contributions to Recreations of the Rabelais Club were du Maurier's "Aux poètes de la France," a poem in French inspired by an argument with Henry James over the relative merits of English and French verse (volume two), and a doggerel poem in English (volume three).

Three illustrations from Hardy's The Hand of Ethelberta

When du Maurier illustrated Thomas Hardy's serialised The Hand of Ethelberta (plates) for the Cornhill magazine (July, 1875, through May, 1876) he and not the novelist was the more significant figure in the eyes of the reading public, in large measure because of his "English Society at Home" sketches in Punch, to which he had already contributed for fifteen years (ten of those as a staff artist). He was known, too, through his illustrations for W. M. Thackeray's Henry Esmond (1869), Foxe's Book of Martyrs and eight works by Elizabeth Gaskell: Sylvia's Lovers(1863); Cranford (1864); Lizzie Leigh, The Grey Woman, and Cousin Phillis (one volume, 1865); Wives and Daughters (1866); North and South (1867); and A Dark Night's Work(1867). His eleven Ethelberta drawings feature little of Thomas Hardy's Wessex countryside, being largely elegant visions of British high society as seen from the perspective of the servants' hall.

These contain a notable preponderance of female figures, and the heroine herself appears in ten of the eleven full-page illustrations. We see Ethelberta in the drawing-room, in the country, on the seashore, Ethelberta in a carriage, on donkey-back, being kissed -- the variety of situations being accompanied by a diversity of costumes, with an effect not unlike a series of fashion-plates" [p. 462]

So impressed was Thomas Hardy by this pictorial programme of eleven drawings and eleven vignette initials that he specifically requested the publisher to contract du Maurier to illustrate A Laodicean for Harper's New Monthly Magazine (December 1880-December, 1881; Discussion of plates). The volume of correspondence indicates that there was close collaboration between the pair, and that the artist felt constrained by the novelist's highly detailed instructions regarding a countryside with which du Maurier was quite unfamiliar. Hardy even sent him two photographs to serve as models for the chief characters, and a photograph of the tumuli that are a peculiarity of the Wessex landscape. du Maurier was the only artist to illustrate more than one of Hardy's novels; unluckily for du Maurier, these are two of Hardy's slightest productions.

Other notable works that du Maurier illustrated include M. E. Braddon's Lady Audley's Secret (1866: one picture for the "yellow back" edition's cover), Wilkie Collins's Poor Miss Finch, The Moonstone, The New Magdalen, and The Frozen Deep (1875: one plate each), and his own novels Peter Ibbetson (1892: 86 illustrations), Trilby (1894: 120 illustrations; selected plates), and The Martian (1898: 48 illustrations).

"Most of these illustrations are competent and pleasant supplements to the texts but some of them, such as in [Douglas Jerrold's] The Story of a Feather [1867] and [Richard Barham's] The Ingoldsby Legends [1866] are superior works of art in themselves." (Kelly 15)

During the 1880s du Maurier suffered a series of disappointments, most notably being passed over for the editorial post at Punch when ill-health occasioned Taylor's resignation in 1880. "Henry Harper, who, with Thomas Hardy, went to lunch at New Grove House [du Maurier's Hampstead residence] on the day of the election, 21 July, to discuss the illustrations of Hardy's A Laodicean in Harper's Monthly Magazine" (Ormond 361) broached the possibility that Frank Burnand would be appointed by the owners. du Maurier appeared nervous, probably thinking himself in the running and Burnand, a Catholic, out of it since Punch was known to have an anti-Papist bias. However, Burnand was chosen. On December 10, 1880, Harper's London agent, R. R. Bowker, visited New Grove House to discuss the Laodicean plates, which both he and Hardy were finding disappointing. du Maurier and Harper's consequently parted company for a time, until Bowker was succeeded by James Ripley Osgood, who persuaded du Maurier to contribute cartoons in 1886, and eventually the novel Peter Ibbetsonin 1891. When Henry Harper accepted Peter Ibbeston for serialisation in Harper's it seemed logical to him that du Maurier be commissioned to illustrate his own novel. Even Henry James, a critic generally severe about illustrated fiction, was lavish in his praise of the forty-eight plates in his 1897 review of the book.

Most of du Maurier's illustrations appeared in the Cornhillfrom 1863 through 1886, including plates for R. E. Francillon's Zelda's Fortune (sample plate), William Black's Three Feathers, and Margaret Oliphant's Carità. He illustrated only two first-rate novels, George Meredith's The Adventures of Harry Richmond, which ran in the Cornhill from September, 1870, though November, 1871, and Henry James's Washington Square(1880). He contributed the frontispiece to the C. S. Reinhart-illustrated volume edition of The New Magdalen by Wilkie Collins, which had run serially in Temple Bar from October 1872, through July 1873. Despite his allegiance to the Cornhill and Punch, his illustrations appeared in a number of other London literary magazines from 1860 until his death: The Illustrated London News in 1860, Once a Week (1860-1867), Good Words (1861 and 1872), the Illustrated Times in 1862, London Society(1862-1868), the Sunday Magazine(1864), The Leisure Hour (1864-1865), Harper's Magazine(1880-1897), and the English Illustrated Magazine (1884 and 1887).

Five illustrations from The Martian.

In the 1880s du Maurier turned his hand to water-colours, but his emphasis on line and his inadequate sense of coloration rendered them little more than tinted drawings. In his novel-writing du Maurier was more successful, producing three novels: Peter Ibbetson (1889), the best-seller Trilby (1894), and The Martian (1897). The popularity of Trilby owes much to du Maurier's handling of the theme of the fallen woman with a good heart, the romantic setting of Paris's Latin Quarter, and the Bohemian characters, the classic Victorian heroine, the Hungarian musician and mesmerist Svengali (under whose sinister influence the young singer falls), Little Billee (modeled on the illustrator and genre painter Frederick Walker, 1840-1875), and Mimi la Salope.

Three illustrations from Trilby.

The critics and the public alike adored Trilby, the story of a vivacious French girl and a satanic hypnotist. Across England and America, it became the number one best-seller in 1894; indeed, by the end of that year it had sold 300,000 copies. du Maurier's chief source (other than his own youthful Continental experiences) was Henri Murger's Scènes de la Vie de Bohème (1845)-- coincidentally, the basis for the Puccini opera La Bohème. However, du Maurier's treatment of his materials differs so greatly from Puccini's because his English, domestic, and middle-class sensibilities make the morally prudish Little Billee the true protagonist.

du Maurier focuses most of the sexuality in this novel upon two things: Trilby's famous foot, which, in paintings, sculptures, and in the flesh is adored by Little Billee and her other admirers; and upon the relationship between Svengali and Trilby. (Kelly 89)

This relationship is clearly drawn from the Sensation novels and stories that du Maurier illustrated in the 1860s and 1870s, notably "The Notting Hill Mystery," published in Once A Week in 1861, and "The Poisoned Mind," published in that same periodical in 1862, although one may certainly detect the influence of Dickens's John Jasper and Rosa Bud from The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) on the relationship between Svengali and Trilby.

By corrupting Trilby and using her like an exotic musical instrument, thereby reducing her to this morbid condition . . . , Svengali also destroys the only person who can restore to Little Billee his own lost romantic vision of a world built upon love, fellowship, and freedom. (Kelly 104)

Svengali's intense hatred of his rivals for Trilby's affections (her old friends, the artists Little Billee, the Laird, and Taffy) precipitates a heart-attack, whereupon the singer awakes as if from a dream, unaware of her celebrated singing career and, indeed, unable to sing at all. Exhausted from years as Svengali's puppet, she dies shortly after her master, and Little Billee, broken-hearted, dies shortly after her.

Almost immediately after du Maurier's death in 1897, the mania that had swept England and America regarding Trilby began to subside after having raged two years. At its height, Trilby boots, shoes, silver scarf pins, parodies, and even sausages flooded the market. Hollywood's first film based on the novel, Svengali, appeared in 1922, re-made as a talkie by the same director, Walton Tully, in 1931, with John Barrymore in the lead. Noel Langley, director of the incomparable black-and-white adaptation of Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol (1951) with Alastair Sim as Scrooge, directed a British film adaptation of Trilby in 1954. The most recent version, made for television, starred Jodie Foster as a rock-star Trilby. Undoubtedly, so durable a creation is the villain Svengali, that we have not seen the last of him on stage and screen.

Late in 1894, du Maurier began work on his third and final novel, The Martian, a romantic fantasy in which an earthling becomes possessed by the spirit of a female extraterrestrial. The first instalment ran in Harper's Monthly for the very month in which du Maurier died, October, 1897. He passed away not in his beloved Hampstead, but in Oxford Square, near Hyde Park, where he and his wife had inexplicably moved in 1895. He was only sixty-two, his death the result (like Svengali's) of heart failure. Everyone of importance to him in life who still survived turned out for his funeral in Hampstead Parish Church, including many distinguished writers and artists, the Punch staff, and his old friends Armstrong, Lamont, Poynter, and Henry James. On his memorial panel in the Hampstead cemetery are inscribed the last two lines of Trilby, his own translation of a couplet from Léon Monté-Naken's "Peu de Chose": "A Little trust that when we die / We reap our sowing. And so — good bye!"

Bibliography

Goldsbury, Dennis. "du Maurier, George." Victorian Britain, An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York: Garland, 1988. Pp. 230-231.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Kelly, Richard. George du Maurier. Boston: Twayne, 1983.

Ormond, Leonée. George du Maurier. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969.

Page, Norman. "Thomas Hardy's Forgotten Illustrators." Bulletin of the New York Public Library 77, 4 (Summer, 1974): 454-463.

Last modified 19 January 2011