This text from the 1890 Magazine of Art, which has been scanned, translated into html, adapted to Victorian Web house style by George P. Landow, may be used for any educational or scholarly purpose without prior permission and long as you cite the Victorian Web. Numbers in brackets indicate page breaks in the original double-column print edition in order to allow users to cite or locate the original page numbers. du Maurier's drawings preceding and following the text and the decorative initial "W" with which it begins appear in approximately the position as they have in the original article.

HEN the Editor of this Magazine first expressed to me his

flattering wish that I should

write down, for him to print,

my ideas on the subject of book

illustration, I was much embarrassed. I felt that of all subjects in the world, this was

perhaps the one on which I had the least and fewest

ideas; that such ideas as I had consisted principally

in my admiration for so many illustrations by others,

in my dissatisfaction with so many illustrations of

my own, in the wonder that there should be so

many illustrated books, good, bad, and indifferent; and that the taste for them should rather seem to

be on the increase than otherwise.

HEN the Editor of this Magazine first expressed to me his

flattering wish that I should

write down, for him to print,

my ideas on the subject of book

illustration, I was much embarrassed. I felt that of all subjects in the world, this was

perhaps the one on which I had the least and fewest

ideas; that such ideas as I had consisted principally

in my admiration for so many illustrations by others,

in my dissatisfaction with so many illustrations of

my own, in the wonder that there should be so

many illustrated books, good, bad, and indifferent; and that the taste for them should rather seem to

be on the increase than otherwise.

Evidently the illustrated book is a "felt want." The majority of civilised human nature likes to read, and a majority of that majority likes to have its book (even its newspaper!) full of little pictures. Evidently, also, there are two classes of readers.

There, is the reader who visualises what he reads (at the moment of reading) with the mind's eye, unconsciously, perhaps, and without effort, but in a manner so satisfactory to himself that he wants the help of no picture; indeed, to him a picture would be a hindrance. Another man's conception of the scene or character would interfere with his own, and probably seem to him inferior; just as many people would sooner read their Shakespeare for themselves than see him acted on the stage or hear him declaimed by an elocutionist. To such a man two is company, three is none.

The greater number, I fancy, do not possess this gift, and it is for their greater happiness that the illustrator exists and plies his trade. To have the authors conceptions adequately embodied for them in a concrete form is a boon, an enhancement of their [349/350] pleasure. Their greatest pleasure of all, of course, is to see it all acted on the stage. In this way the story unfolds itself to them without any effort on their part; nothin' is left to the imagination, which they may not possess, or, possessing, may not care to exert.

But the stage is not always at one's command, and failing this, the little figures in the picture are a mild substitute tor the actors at the footlights. They are voiceless and cannot move, it is true. But the arrested gesture, the expression of face, the character and costume, may be as true to nature and life as the best actor can make them. Within the limits assigned, these little dumb motionless puppets may be as graceful, or grotesque, or humorous, or terrible as people in real life — indeed, more so , they may continue to haunt the memory when the letterpress they illustrate is forgotten. When they produce this effect, it may be said, I think, that they are the work of a good illustrator; and if, in addition to this, there is the charm of fine handicraft and the cunning of a well-trained faculty, the result is a delightful and valuable work of art — although its scale be a small one, and the means of its production very simple and slight — a very precious possession.

As the highest example of such performance in our time, I will cite Menzel's illustrations to the Life of Frederick the Great (by an author whose name I have forgotten, and whose book I have not read, because it is in German). Whatever the book, the illustrations seem to me for all time, and for any country.

It would be possible, I suppose, and perhaps interesting, to trace the history of book illustrations from its very beginning, which must lie pretty far back in the past. But such a task is not for such as the present writer, and would require a volume for its execution, instead of a magazine article.

I will content myself with recording quickly such impressions, recollections, and general experience as I have of the subject, well satisfied if, in doing so, I meet the wishes of the Editor of this Magazine, and do not impose too much upon the patience of its readers.

Of course, the most delightful illustrations in the world are those one loved when one was young. It is impossible, perhaps, to judge them quite impartially. One may lose one's taste for the text, and no longer relish Harrison Ainsworth or Charles Lever with quite so keen a zest as was the case forty years ago; but the comely forms of Jack Hinton and Harry Lorrequer, and their rollicking brothers in arms, have still power to please, especially when on galloping horses — galloping from one scrape to another, from the old love to the new. And the headsman, cutting off the head of Lady Jane Grey, is as thrilling as ever, although one may have lived to be more fastidious in the matter of mere execution (by which, of course, I mean the technical craft of the artist). And, indeed, what does not the great Dickens himself owe to Cruikshank and Hablot Browne, those two delightful etchers who understood and interpreted him so well!

Our recollections of Bill Sikes and Nancy, and Fagin, and Noah Claypole, and the Artful Dodger, of Pickwick and the Wellers, pere et Jils, Pecksniff, Mrs. Gamp and Mrs. Prig, Micawber. Mr. Dombey, Mr. Toots, and the rest, have become fixed, crystallised, and solidified into imperishable concrete by these little etchings in that endless gallery, printed on those ever-welcome pages of thick yellow paper, which one used to study with such passionate interest before reading the story, and after, and between. One may have forgotten much that Mr. Pecksniff has thought, or said, or done in this world; but what he looked like, never! And no new portrait of him, by the hand of howsoever consummate an artist, can ever displace the old one for such of us as are in the middle fifties.

It would be interesting to know for certain what Charles Dickens thought of these illustrations — whether they quite realised for him the people he had in his mind, or bettered them, even — for such a thing is not impossible; indeed, it is the business of the true illustrator to do this if he can. I believe that Thackeray was more pleased with the outward shape that Fred Walker had given to his Philip (on his way through the world) than with even his own mental conception of the same, which was quite different.

There was (or rather, happily, there is) another illustrator of this long past period, far greater as a craftsman than than two I have mentioned, Cruikshank and Browne. He did not etch, however; his illustrations were designed on wood, and although most of his pictures were in books, and not of modern life, he did not disdain to illustrate the humble London Journal, that used to appear once a week. It must be nearly forty years ago since I used regularly to buy that paper for Sir John Gilbert's admirable woodcuts, which are, perhaps, now forgotten in the far more important works he has produced in oil and water-colour. But they will never be forgotten by me.

Leech and Doyle are so much better known by their work in Punch than by their book illustrations, that I will do no more than allude to them, excellent as they are. Colonel Newcome and Barnes are well remembered, as well as the "Comic Histury of England," "Mr. Sponge's Sporting Tour," &c. And of John Tenniel, Charles Keene, Linley [350/351] Sambourne, and Harry Furniss I shall have occasion to speak further on.

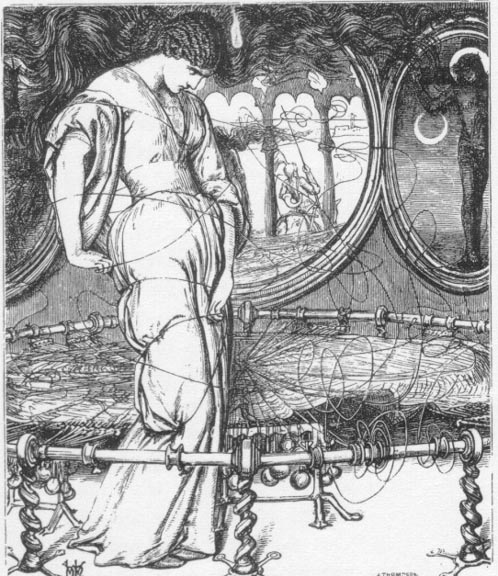

"The Ballad of Oriana" and The Lady of Shalott by William Holman Hunt.

[Neither in original; click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Then, in 1860 [actually 1857], appeared the illustrated volume of Poems, by Alfred Tennyson; and about the same time The Cornhill Magazine and Once a Week were started, whereby a new impulse was given to the art of illustrating books. Millais, Rossetti, Holman Hunt, and others well known to fame, designed small woodcuts for the former most charming volume, the publishing of which made an epoch in English book illustration. A new element was imported, to which I find it difficult to give a name. Anyhow, some of these drawings gave some of us — I can answer for one who wanted to illustrate books — extraordinary pleasure. They do still.

I still adore the lovely, wild, irresponsible moonface of Oriana, with the gigantic mailed archer kneeling at her feet in the yew-wood, and stringing his fatal bow; the strange beautiful figure of the Lady of Shalott, when the curse comes over her, and her splendid hair is floating wide, like the magic web; the warm embrace of Amy and her cousin (when their spirits rushed together at the touching of the lips), and the dear little symmetrical wavelets beyond; the queen sucking the poison out of her husbands arm; the exquisite bride at the end of the Talking Oak; the sweet little picture of Emma Morland and Edward Grey, so natural and so modern, with the trousers treated in quite the proper spirit; the chaste Sir Galahad, slaking his thirst with holy water, amid all the mystic surroundings; and the delightfully incomprehensible pictures to the Palace of Art, that gave one a weird sense of comfort, like the word "Mesopotamia," without one's knowing why.

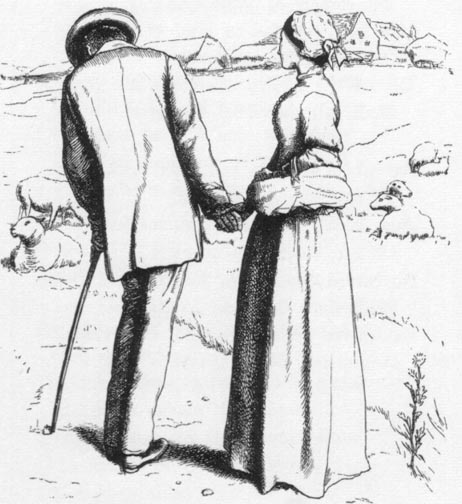

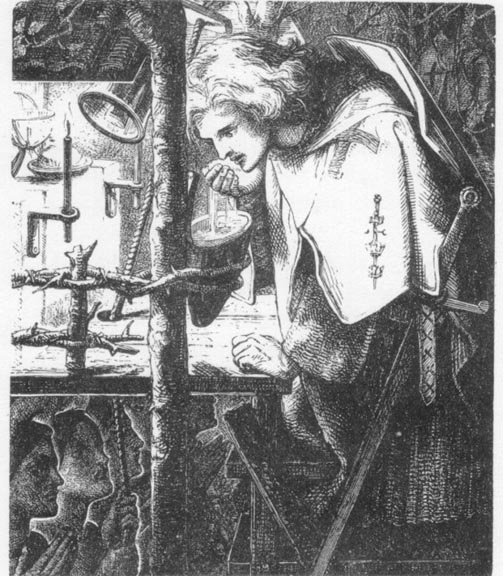

The Talking Oak and Edward Grey by J. E. Millias; right: Sir Galahad by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. [None of images appear in the original essay; click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Then it was that Once a Week and The Cornhill Magazine came, with Millais, Fred Walker, Charles Keene, Frederick Sandys, Pinwell, and others. The life of our time — which had been illustrated humorously by Leech, Doyle, and Keene in Punch; humorously and seriously by Hablot Browne in Dickens and Lever; and by Sir John Gilbert in The London Journal — was now being treated from quite a serious point of view.

The chimney-pot hat and the trousers, the crinoline and the spoon-bonnet were taken in hand by cunning craftsmen, and duly "invested with artistic merit;" the artist trusted no longer to his impressions, his memory, his inner consciousness. The model became as indispensable to him as to the historical painter. He made elaborate studies of the fashionable skirt, sleeve, body, bonnet, and shawl, as though he were concerned with some great classical design.

Not, indeed, that it was all modern English in either Once a Week or The Cornhill. The reader will remember Charles Keene's beautiful cuts to "The Cloister and the Hearth;" and others by Millais, Leighton, Sandys, Poynter, Lawless, Tenniel, in which the costume was of another time and clime.

Frederick Walker, then quite a boy, leapt into fame by his illustrations in Once a Week and The Cornhill Magazine. I can find no words to express the admiration I felt for them as they appeared one after another, each better than the last, till they culminated in the famous picture of "Philip in Church;" an admiration that left no room for any petty feeling of personal envy.

He had founded himself, I think, partly on Sir John Gilbert, partly on Sir John Millais; but in an incredibly short time he became Fred Walker, a rock for the foundation of others; for he has made school, as the French say, in wood-draughtsmanship, as well as in oil painting and water-colours.

Putting aside the charm of his composition, the grace and naturalness of his figures, the sweetness of his landscapes, the exquisite deftness and dexterity of his manipulation (those effective little cross-hatchings that are to be found more or less in almost every woodcut executed since his time), he was the first to quite understand, in their "inner significance," the boot, the hat, the coat-sleeve, the terrible trousers, and, most difficult of all, the masculine evening suit. Even Millais and Leech, who knew the modern world so well, could not beat him at these.

So that I look upon Sir John Gilbert, Sir John Millais, and Frederick Walker as the grandfathers and fathers of our modern school of illustration; that is, of such illustration as illustrates the life of to-day, which, of course, is not everything. For the most successful illustrated English books of our generation — at least, I venture to think so — have not treated of the immediate life around us. For instance, in the two little books that describe the adventures of "Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," the pictures seem to me simply perfect, but that I should have preferred for Alice herself a more really childish figure of a child. The stories are charming in themselves, but what has Mr. Tenniel not done for them besides It is like Sir Arthur Sullivan's music to Mr. Gilbert's delightful librettos. These little pictures are a joy for ever; they stick in the mind like charming tunes that won't allow themselves to be forgotten. Whatever may be the ultimate fate of the words, the cuts are truly creations. Of course, they belong to the old school — the good old school — the Mock-turtle and the Jabberwock have not been drawn straight from nature. Perhaps we, of the new school, are too much the slaves of the model — a pernicious habit [351/352] has to deal with Jabberwocks and Mockturtles.

Then there are the two books about "Bracebridge Hall'" and "Christmas," by Washington Irving, which have been brought back to vigorous life by Randolph Caldecott, a true illustrator, if ever there was one. That is, an enhancer of the charm and humour of his text, wliose art seems of the slightest — a very few strokes were enough for him to work wonders with. It is magic ! Grace, charm, beauty, humour, character, pathos — all were his; and he was as skilled in landscape and animals as in the human figure, and " good alike at grave or gay." There is also his immortal series of picture-books, equally beloved by old and young and middle-aged, by babies even — a gallery that never palls.

I must also mention Mr. Walter Crane's beautiful and not-to-be-forgotten coloured pictures to the fairy tales, and Mr. Linley Sambourne's illustrations to the "Water-Babies," and Miss Kate Greenaway's nursery rhymes.

Nor, among the great English illustrators of our day, must I omit the gifted Frenchman, Gustave Doré'; whose weird genius, however, seems to have been most successful when its inspiration was drawn from French sources — Rabelais and Balzac. His drawings to the Bible are wonderful enough, but not conceived in an English spirit; those to the is "Idylls of the King" are, I think, a failure.

The old Cornhill Magazine, even more than Once a Week, has a high record as an illustrated periodical. In it, no less important a novel than "Romola" was illustrated by no less important a person than the present President of the Royal Academy; "Framley Parsonage" and "The Small House at Allington," by Millais; "Philip on his Way Through the World" by F. Walker; "Far from the Madding Crowd," by Mrs. Allingham (Helen Paterson); George Leslie, Luke Fildes, Marcus Stone, now Royal Academicians; F. Dicksee, A.R.A.; W. Small, F. Sandys, and others have also illustrated those brilliant pages. And for many years I had the honour and pleasure of providing every month a page-drawing and an initial letter. That illustrated Cornhill is no more; and the old Once a Week has long become extinct. To parallel them for the merit and interest of their illustrations we must seek across the Atlantic.

There are, as perhaps the reader knows, two different ways of drawing for wood. One is, to paint a finished picture in black and white, using the brush and washes of different degrees of intensity; picking out the lights with white, or leaving the white paper for them. The engraver translates this in his own way, cutting his own lines to represent or, rather, interpret the value of the tone left by the artist. In this case the artist is very much at the mercy of his engraver. Moreover, little is left to the imagination. Every detail must be put in — background, sky, wall, the ground, the grass, tha carpet; no blanks are left, except here and there where the light falls on a white surface, between which and the blackest point of the picture is employed every possible shade of grey. Speaking from memory and under correction, I believe The Graphic was the first illustrated paper to encourage this school in England. In its first number was an admirable picture by Luke Fildes, R.A., "The Casual Ward" (from which he afterwards painted a work in oils), and, if I remember rightly, it was treated in this manner. And since then, in the pages of The Graphic have appeared many illustrations of the highest merit by Frank Holl, Luke Fildes, H. Herkomer, H. Woods, W. Small, A. Hopkins, Miss Thompson (Lady Butler), C. Green, Sydney Hall, E. Gregory, J. Nash, G. Durand, Paul Renouard, and many others; built, I believe, on the same principle, namely, the interpretation of the tone which the artist has laid in with a wash, by the engraver, who uses lines more or less thick, or dots, or hatchings of his own, according to the depth of the tone wanted. Parallel with The Graphic runs The Illustrated London News.

The other way is to draw one's picture with pencil, or, better still, with pen and ink, using a simple conventional black outline to give the shape and enclose the form and face; then adding more lines and pen-and-ink scratches, simple or cross-hatched, to suggest colour and tone, as an etcher does with his needle, and leaving blank all that the artist judges non-essential to his picture — leaving it in fact, to the imagination. The engraver cuts all this in facsimile; it is more than his place is worth to add a line of his own, or leave out one of the artist's. Or it may be "processed."

It does not do for two pictures — one of them designed in the first manner, the other in the second — to appear in juxtaposition on the same page; the first by its completeness, and depth of tone and colour, kills the second. Yet I confess that, to me, the second is the more attractive of the two.

Among the followers of the first mentioned school (if, indeed, he be not one of its originators) I will cite, as an example, Mr, William Small, whose admirable illustrations are so well known to the readers of The Graphic. But to fully appreciate the beauty, power, and delicacy of his work, one must see it in the original design, before even the best of engravers has had his will of it.

Mr. Edwin Abbey is an equal master of either method. He has shown us, in his beautiful illustrations to "She Stoops to Conquer," specimens of his [352/353] perfection in both. I have seen the originals, and as far as his absolute craft is concerned, I don't know which of the two to admire the most. But for my own taste, I infinitely prefer the scratchy pen-and-ink designs, which give just the essence of what one most wishes to see, and leave out everything else; and then, when the drawings are duly "processed" and printed, no interpreter comes between Mr. Abbey and myself, no middle-man.

Therefore, the latter method seems to me the highest and most legitimate; the most fascinating when it is well done, and by far the hardest to do well. It was the method of J. Gilbert, J. E. Millais, and F. Walker, among many others. It is the method of Mr. Charles Keene, who is universally admitted (especially by those who know, because they have tried to do it themselves) to be the greatest master of the art of drawing on wood with pen and ink that we have, or ever have had. His knowledge of what can be done with mere black lines of different thickness to give the illusion of light and shade, colour, shape, texture, weather, nearness, or distance, and his instinct, especially, for feeling what he ought to leave out, or can afford to leave out — seem to me to be only matched by a like knowledge and instinct in the German Menzel. If his picture were executed in washes, and made a literal transcript of nature in black and white (however well), how infinitely it would lose of light and breadth, of freedom and breeziness, and large and happy suggestiveness! It would cease to be the work of a conjurer.

It is a far cry from Small's method, and Abbey's, and Keene's to R. Caldecott's, who can tell so much in a little pen-and-ink outline! One may have one's individual preferences, but who can say, for certain, that one method is better than another ?

As for the book illustrators of our day, they are many and admirable, whatever their method. Besides those I have named, there are Caton Woodville, Barnard, Sullivan, Parsons, Millet, Reinhardt, Partridge, and others, whose names escape me at the moment — only to be remembered when it is too late, probably. But many as they are, they are not too many for the work they have to do, and their number will have to be increased. In mere technical equipment they immeasurably surpass their popular predecessors, Cruikshank and Hablot Browne. In all arts and crafts the standard of mere technical excellence seems to have gone up, and to be easily reached by a far greater number of aspirants; in painting, verse-making, play-writing, the padding of magazines', the scoring of music, the dexterous pouring of old wine into new bottles, and what not! — in all, perhaps, save the manufacture of novels, whereof the humble illustrator has a right to his opinion, since he has sometimes to read and re-read them so carefully. And if the disappointed author says to him "Why can't you draw like Phiz?" he can fairly retort: "Why don't you write like Dickens?"

As a matter of fact, however, such amenities are not often exchanged between author and artist; and I, for one, have met with nothing but kindness and courtesy from those I have illustrated. When I have failed to please, the only revenge has been a discreet silence; indeed, in one case, where I failed conspicuously and disastrously, through the unsuitability of the subject-matter to my pencil, the author has heaped coals of fire on my liead, by becoming my intimate friend. It is true that I only accepted the commission to please the publisher, who was the common friend of us both, not seeing at the time how unfit I was for this particular task.

And here, at the risk of letting it be thought that I am too much puffed up with vaingloriousness, I will go so far as to say that on three or four occasions I have actually been the recipient of compliments and thanks from the author himself in his own handwriting". I will even mention the names of Mr. George Meredith, Mr. Thomas Hardy, and Mr. James Payn; and hereby return my compliments and thanks for theirs.

Bibliography

du Maurier, George. "The Illustration of Books from the Serious Artist's Point of View. — I." Magazine of Art (1890). London: Cassell and Company. 349-53.

Last modified 21 December 2023