t is sometimes the case that talent runs in families. The Brontë clan – Emily, Anne, Charlotte and Branwell – is a good example of siblings sharing artistic ability, and the creative impulsive is sometimes passed down through the generations. George Cruikshank’s father Isaac was an artist, and George’s brother, Robert, was also a practising designer in black and white. This intergenerational transmission becomes the ‘family trade,’ a situation that is especially evident in the case of the Doyles.

The founder John Doyle (1797–1868) was a celebrated cartoonist, and each of his four sons became an artist, or practised art alongside another occupation: Richard Doyle (1824–83) became a famous illustrator, one of the foremost book-artists of his time, noted for his designs of fairies, interpretations of Thackeray and Dickens, and satirical commentaries; James (1822–92) was a historian and artist, most associated with his coloured wood engravings in The Chronicle of England (1865); Henry (1837–92) was a portraitist, illustrator, and a director of the National Gallery of Ireland; and Charles (1832–93) contributed many illustrations to the periodical press as well as embellishing a number of books. The Doyle brothers’ creativity was also projected into the next generation, this time in the form of Charles’s son, Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930), the doctor who created Sherlock Holmes and wrote a series of influential adventure and supernatural tales such as the proto-mummy story, ‘Lot No. 249’ (1892).

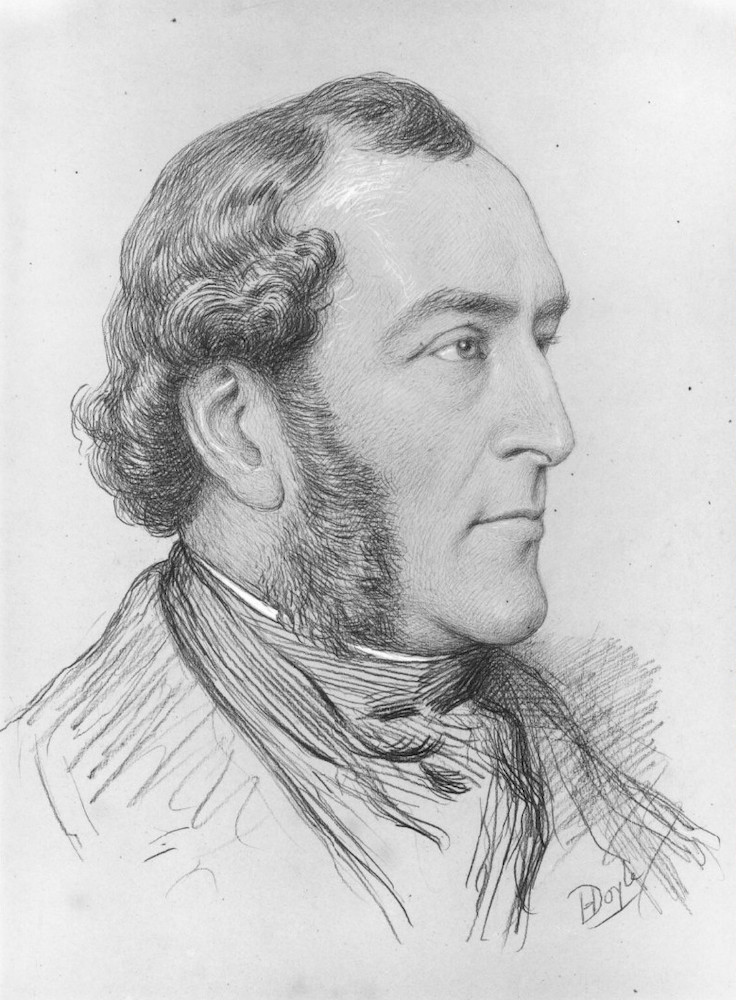

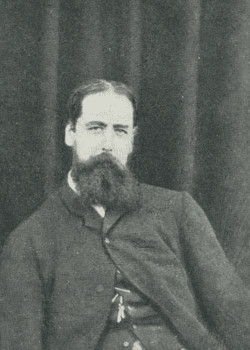

Five of the prodigiously talented Doyles, left to right: John Doyle (‘HB’, by Henry Doyle © National Portrait Gallery, London); Richard (after a photograph); photographs of Henry (also © National Portrait Gallery) and Charles (with Arthur Conan Doyle as a child, in The Bookman (Nov. 1912); and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle as an old man, oil by Henry L. Gates. I have not been able to trace a likeness of James.

Popular in their own time, each of these family members had a significant impact on Victorian culture, and Conan Doyle is still influential today. Interesting, too, is the way in which the Doyles shared a number of ideas and preoccupations. These varied between satire and the fantastical, close observation of nature and the imagined world of fairies and fairy-tales. How these themes were presented as the common language of a highly creative family, intermingling in a series of complex connections, and sometimes sharing imagery, is worth considering.

Imagery and Idiom: Portraiture

All of the Doyle artists were good portraitists, basing their reportage on a close observation of their subjects’ faces and gestures. The interest in verisimilitude was established by John Doyle, who had painted portraits before he turned to satirical prints.

Much of the impact of John Doyle’s political satires was based on the accuracy of his portraiture, which had to present accurate likenesses of his targets in order to make fun of them. In contrast to Gillray and Rowlandson, who used grotesque exaggeration to convey their satirical point, Doyle aimed to stimulate his viewers’ recognition of his subjects – which could then be ridiculed by placing them in ludicrous situations. Considered purely as portraits, however, his images of contemporary politicians are a valid historical record which helped to familiarize a large audience with the appearance of the nation’s leaders; tellingly, the most complete collection of Doyle’s prints is held in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Indeed, the accuracy of Doyle’s representations is revealed in a comparison between his treatments and those of formal, ‘official’ portraits. It is instructive, for example, to compare his image of Palmerston in The Last of the Roses (1842) with John Partridge’s oil, and we might also compare his representation of Daniel O’Connell in An Extraordinary Animal (1835) with an engraved portrait by Samule William Reynolds (1844). Doyle based his likenesses on sketches made in the lobby and public gallery of the Houses of Parliament, and were as closely observed as they could be within the dynamic context of governmental business as politicians gave speeches, talked to each other, and spoke to interested parties. Equipped with his sketch-book, and working covertly so that none of the politicians knew they were being observed, Doyle managed to create an unusually intimate record of his ‘marks.’

Left to right: John Doyle’s The Last of the Roses; and John Partridge’s portrait of Palmerston.

Daniel O’Connell’s face was mediated throughout the print culture of the period. Left to right: John Doyle’s An Extraordinary Animal ; and Thomas Carrick's portrait of O'Connell.

John Doyle’s practice was taken up by his sons. A notable example is Henry Doyle’s portrait of his father (see above), which shows him in intense detail as an imposing patriarch. Richard and Charles also directed the portraitist’s gaze onto the family. Richard visualizes his own and his siblings’ appearance, especially in his Journal (6) and illustrated letters, and Charles provides a series of self-portraits in his Diary (Baker, plate 7) as he struggled with mental illness and was incarcerated in an asylum in Edinburgh. These are thoughtful, reflective images which encapsulate his family members’ physical and psychological profiles at key moments in their lives – as children, and in middle-age.

For the most part, though, the emphasis was on those outside the family. Richard emulated his father’s close observation of political figures, designing a wide range of caricatures for Punch which contained portraits, among others, of Disraeli, Brougham and Wellington. Again, these are so accurate as to seem ‘from the flesh,’ though it is not known if Richard adopted his father’s strategy of watching politicians in the House. He certainly observed at first hand the faces of dinner-guests at venues he attended, as well as making vivid likenesses of his friends, colleagues and collaborators.

Richard Doyle’s caricature of Dickens, Forster and Jerrold, © The Trustees of the British Museum (asset number 314677001).

One of the most telling of these is a pen and ink drawing of Douglas Jerrold, Dickens and John Forster, a work which mediates between realism and caricature. This design exemplifies the intermingling of two contradictory elements in Richard Doyle’s art, conflating verisimilitude and a satirical desire to distort and simplify for comic effect.

Social Satire

Richard Doyle developed the satirical tradition established by his father in the pages of Punch, infusing his ‘big cut’ cartoons with a droll humour that went well beyond the restrained politeness of ‘H.B;’ John Doyle’s caricatures were often too refined to raise a laugh, but Dicky Doyle’s were always amusing – and enjoyed considerable popularity with the magazine’s viewers.

Doyle produced his political cartoons in parallel with John Leech, Punch’s primary artist. As Leech’s second, Doyle followed Leech in focusing many of his designs on social satire rather than the behaviour of individuals, reframing some of his commentaries on the result of political policies, at home and abroad, rather than those who created them. In so doing Doyle offered his own version of Leech’s hard-hitting attacks on foreign and domestic policy, ameliorating Punch>/span>’s radical message while still making a sharp attack on the chosen target.

The artists’ differing approach is exemplified by the contrast between Doyle’s ironically titled Britannia’s Thanksgiving Day Dream (1849) and Leech’s The Poor Man’s Friend (1847). Both respond to the sufferings of the urban working-classes in the 1840s, and both appeal to the bourgeois readers’ conscience. Leech invokes horror by depicting the unemployed labourer as abandoned by the state and even by the Christian faith; all he has, in response to his prayer, is unforgiving Death.

Left to right: John Leech’s The Poor Man’s Friend, and Richard Doyle’s Britannia’s Thanksgiving Day Dream (1849).

Doyle, by contrast, implies the indifference of Britannia and the British Lion as they sleep or day dream while the working classes, who constitute the oppressed majority of the population, are reduced to terrible suffering by poverty and the effects of a recent cholera outbreak Doyle’s design does not have the emotional supercharge of outrage inscribed in Leech’s, but it does display his angry awareness of the neglect of the ruling classes and, in its own way is just as radical as Leech’s illustration. Indeed, he occasionally ventured into Leech’s emotional range, offering, among others, painful commentaries on slavery.

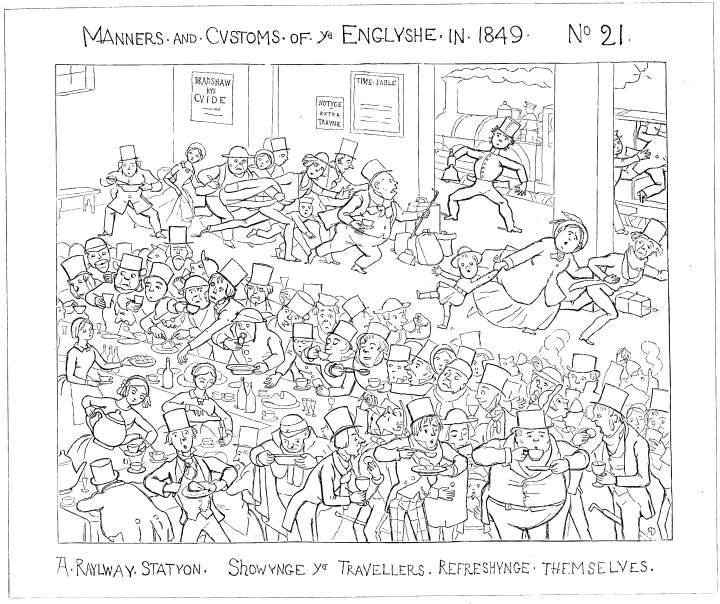

Generally, though, Richard Doyle’s Punch satire is understated; though a much more effective humourist than his father, he creates a visual continuum with H.B.’s prints. Richard develops his polite satire in his picture books, Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe (1849), Bird’s Eye Views of Society (1863–4) and The Foreign Tour of Messrs. Brown, Jones and Robinson (1855). In these publications he shifts from radical commentary on ‘social problems’ and the Condition of England to satirizing the mores of the bourgeoisie at play.

Richard Doyle’s farcical comedies of manners. Left:A Railway Station (1849), showing the frenetic efforts to catch the train in the period when British trains ran on time; and Right: :Robinson Asleep (1854), showing one of Doyle’s inept travellers overcome with cultural exhaustion, incapable of cramming any more ‘experiences’ into his overladen tourist’s mind.

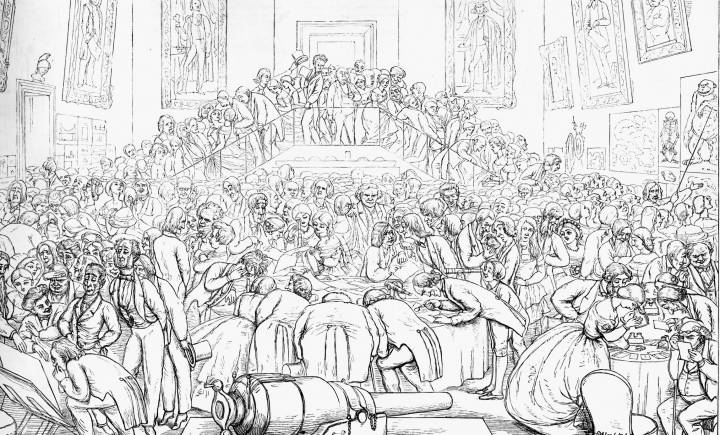

Richard shared this theme with his brother Charles, and there are many points of resemblance between the artists’ treatments. Both illustrators stress the dynamic intensity of crowd-scenes: for example, the breathless movement of Richard’s milling figures in Manners and Customs is matched by the intricate scenes in Charles’s illustrations, notably in his design of London and What we Did at the Seaside. The compressed space in both artists’ work intensifies the sense of oppressive social proximity as the figures seem to be fighting for the right to conduct their leisure activities; Richard Doyle’s An Art and Science Conversazione (1863–4) takes the situation to its absurdist extreme, but Charles also focuses on the cramped hurriedness of what is supposed to be a relaxing event, as in the tense contemplation of a shot in Golf (1862). Struggling not to survive but to enjoy themselves, the brothers’ sets of figures seem paradoxically to be far more stressed and overwhelmed by modern living than if they were engaged in a non-leisure activity. There is also a marked similarity between the siblings’ linear manner, with Charles’s What we Did at the Seaside (1863) being drawn in the febrile outline style that Richard deploys in Bird’s Eye Views of Society.

Charles Doyle’s treatment of the comedy of manners, which bears direct with his brother Richard’s social satire. Left: London (1874), all bustle and movement; and right: What We Did at the Seaside (1862), another version of the idle bourgeoisie getting bored doing nothing.

Richard and Charles essentially work in tandem in their creation of this sort of social satire, which suggests they shared ideas and looked at each other’s work. Richard was by far the more celebrated and successful of the brothers, and it might be assumed that he was the dominant figure; however, it is interesting to note that Charles’s cartoons in London Society appear in 1862–3, predate Richard’s Bird’s Eye Views of Society (1863–4), and could have been an influence on the development of that series. What we can say with certainty is that the Doyles – John, Richard and Charles – were united in their focus on social and topical satire, providing a detailed portrait of the age in a series of mocking images which are linked within the aesthetics of caricature.

Charles and Richard produced work which converged at several key moments, and there is marked stylistic similarity between the brothers’ treatments of social satire, as in these two examples. Left: Charles’s Golf (1862–3), and right: Richard’s An Art and Science Conversazione (1863–4). These leisure activities seem to be oppressive – the struggle to enjoy one’s self, rather than relax as everyone is animated by febrile energy.

History and Mock-History

History was a key part of the Doyle family’s art: though deeply engaged with contemporary life, the artists looked backwards as much as forwards. John Doyle makes many historical allusions in his prints, and all four of the brothers, who read history as part of the educational programme devised by their father, were concerned with the English past. In each case, they interpreted the information in their own terms.

James wrote and illustrated the Chronicle of England (1864), depicting the sweep of history from the age of the Romans to the death of Richard III. James’s written account is a purely conventional re-telling of the chronology; his book is more interesting, however, for its vivid coloured illustrations, which were engraved and printed on wood by Edmund Evans (the engraver who was later to produce Richard Doyle’s masterwork, In Fairyland,1869–70).

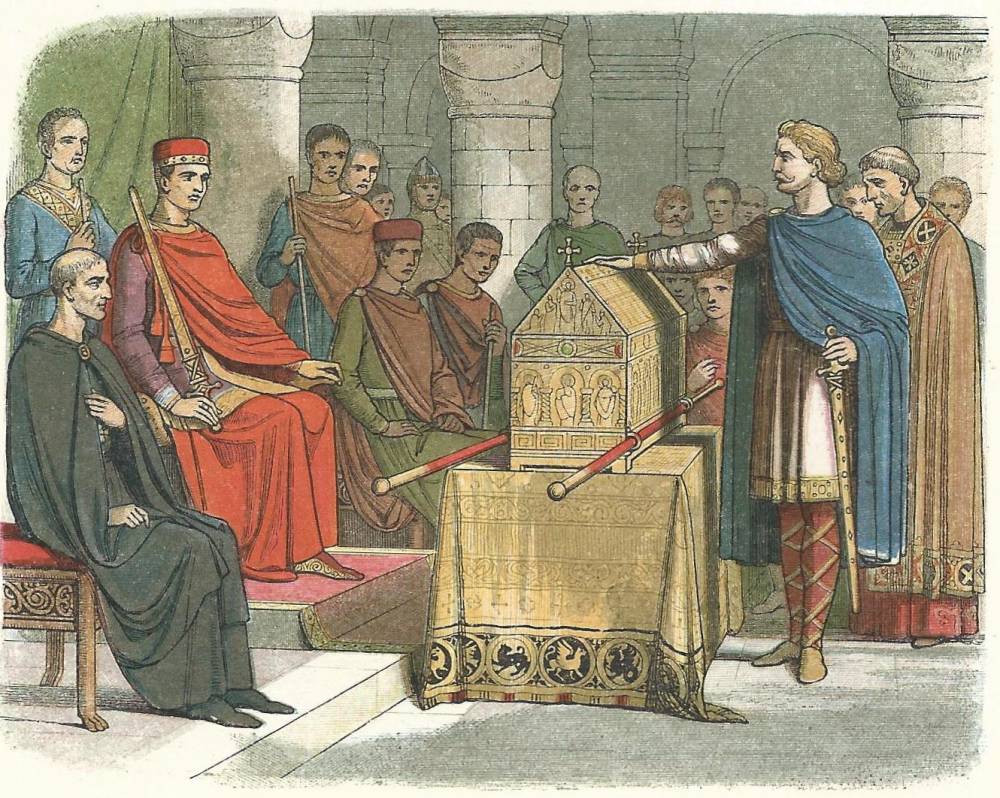

James’s designs offer a montage of English history as it moves between the opposites of conflict and negotiation, conversation and violence. At once extreme are Harold swears fidelity to William and Lady Jane Grey and Edward IV, and at the other illustrations depicting the violent end of Harold at Hastings and Simon de Montfort at Evesham. Doyle purports to show realistic representations of events, but his static draughtsmanship and bright colours invoke in equal measure the simplified effects of a child’s picture-book and the heraldic, gem-like imagery of an illuminated missal. Such artificiality locates the book in the domain of leisure viewing rather than historical inquiry, a book to be shared with parents and children, and the generally good condition of surviving copies suggests the Chronicle of England was inspected but rarely read.

Some examples of James’s historical reconstructions: a) Harold swears fidelity to William; b) The Death of Harold; and c) Lady Jane Grey and Edward IV.

More imposing as an account of real events are Henry Doyle’s visualizations of scenes from Mary Cusack’s Illustrated History of Ireland from AD 400–800 (1868). Henry was an accomplished portraitist – producing likenesses of his father, Cardinal Newman and Dickens – but he was also possessed a talent for inscribing deep feeling in narrative images which goes far beyond the ornamentalism of James’s Chronicle. Cusack’s book gave Henry an opportunity to reflect on his ancestry as the son of an ex-patriot Irishman, and in his designs he painfully evokes the suffering of the Irish as well as projecting the anguish and anger of Irish politicians’ demands for independence.

Henry Doyle’s The Emigrants’ Farewell.

The Massacre at Drogheda exemplifies the sense of outrage, depicting a Cromwellian soldier in mid-gesture as he is about to kill a mother and child – interpictorially alluding to Renaissance paintings of The Massacre of the Innocents – but most effective is the deeply-felt illustration of The Emigrants’ Farewell. Doyle depicts one of the archetypes of the Celtic experience: a farewell from the quayside, with the ship departing and those remaining behind waving goodbye with the knowledge that they will probably never see their loved ones again. The characters’ anguish is enshrined in their gestures, again referring to Italian Renaissance Lamentations of the Death of Christ, and other small details. As Jacqueline Banerjee remarks, the artist

has captured the intensity of emotion shared by old and young, men, women and children, at these terrible partings. Only the small girl, pointing perhaps at a rowing boat returning from taking passengers out to the vessel, may be unaware of the full tragedy of the moment. The father of the family has his hands raised as if in blessing. A cane and cap lie abandoned on the quayside, all that is left to them of the departing emigrant.

Henry Doyle’s achievement, in short, is to interpret real events in emotional terms, translating an historical fact into a human drama. If James could only imagine history as spectacle, a montage of facts enacted by waxwork figures, Henry conveys the impact of history and the suffering of the humble who are trapped in its machinations.

James’s emphasis on chronology and Henry’s invocation of historical experience is complemented by Charles’s and Richard’s interpretations. Charles Doyle’s interest is focused on the notion of the milieux of history – of how the past looked, its fashions, its settings, its physical textures, its manners and its social behaviour. His approach is exemplified by his dense designs for Grace and Philip Wharton’s The Queens of Society (1860), which represent in accurate detail the ‘look’ of the eighteenth century.

Charles Doyle’s The Fair Lepell:

one of the artist’s illustrations of the eighteenth century.

Richard’s approach to history, on the other hand, is in sharp contrast to his brothers’ treatments. Unlike his siblings, Richard deploys the comic burlesque – mocking the great events and characters in the form of travesty and caricature. In Scenes from English History (1840, published 1886), he reduces key moments such as Edward the First presenting his son as Prince of Wales to the level of absurdism as the king dangles his infant in front of a gurning crowd of Welsh nobles at Caernarfon. Here, typically, the humour is based on a combination of situational comedy and the caricature enlargement of the characters’ heads.

Doyle’s cod-medievalism also features in The Tournament (1840), in which he satirizes the early-Victorian yearning for a lost and imagined history.

Richard Doyle’s absurdist history. Left: Edward the First presenting his son, and right, a scene from The Tournament.

His illustrations for Thackeray’s Rebecca and Rowena (1849) are similarly droll and amusing, as he mocks the crusades and the barbaric excesses of medieval warfare.

Richard Doyle’s Ivanhoe Killing Moors.

These humorous designs are in counterpoint to the seriousness of James’s reconstructions, although the connection between the brothers’ sense of history is registered in the texts for Doyle’s Scenes, which were written by James, and invite a mock-heroic comparison with his Chronicle of England (1864).

Fairies and Fantasy in the Art of Charles and Richard Doyle

We can see, in short, how the Doyles’ interests ran in parallel and sometimes converged and overlapped. The closest relationship, however, is in their fascination with fairies and the fantastic, a preoccupation shared between John, Richard, Charles, and Charles’s son, Arthur Conan Doyle.

Richard Doyle was one or the originators of fairy imagery. Developing a discourse that was also practised by Cruikshank in book illustration and by painters such as J. Noel Paton, he became the most celebrated practitioner of this sort of Victorian fantasy, displaying his talent to best effect in Montalba’s Fairy Tales from All Nations (1849) and in his masterwork, In Fairyland (1869–70).

Responding to his brother’s influence – as Richard responded to Charles’s social satire – Charles deploys the same language of ‘little people’ and comic grotesques, often adopting his elder brother’s emphases. Indeed, Charles uses his fairies, as Richard does, as a symbolic code which represents the workings of the unconscious, sexuality, and disturbed mental states: though on the face of it purely ornamental, the brothers’ fairy vocabulary is infused with threat and is often strange and unsettling, embodying messages which might not be represented directly in a highly censorious age.

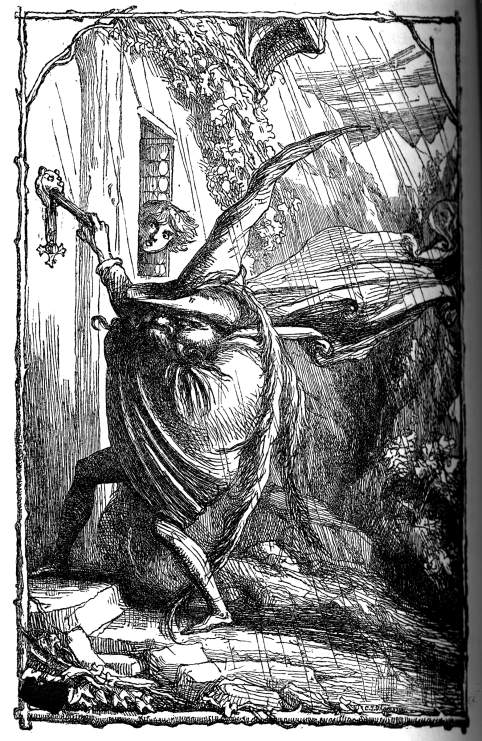

Richard’s use of the fairies as a mental metaphor is exemplified by one of the designs in his Journal, Dick Doyle Surrounded by Malevolent Fairies (1840).

One of Richard Doyle’s (literally) nightmarish takes on fairy world, with sprites and goblins emerging from the semi-conscious mind.

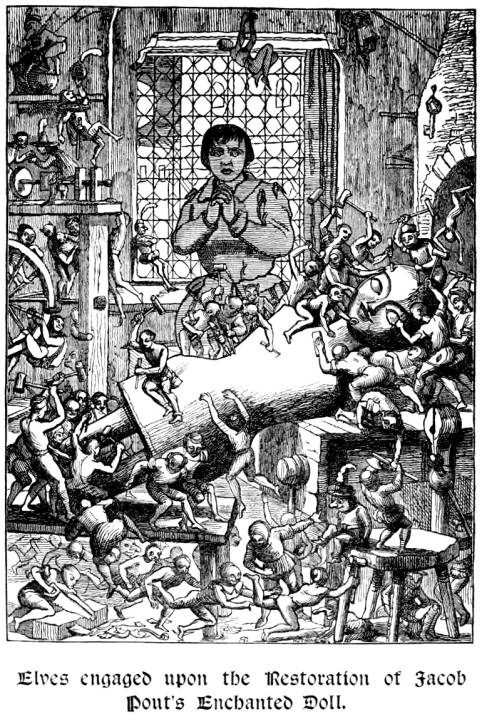

In this image Doyle asserts the oft-asserted association between imps, elves and fairies and dream-like states, depicting his figures as both whimsical and menacing as they emerge from his sleeping mind, a Gothic concept that recalls Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781, Detroit Institute of Arts). The destructiveness of fairies that seem to erupt from the suppressed unconsciousness is similarly suggested by his representation of the teeming figures illustrating Mark Lemon’s The Enchanted Doll (1849) and by the murderous characters in one of his designs for Montalba’s Fairy Tales of All Nations (1849).

Two of Richard Doyle’s representations of the malignity

of the little people, with illustrations to texts by

Mark Lemon (left) and Montalba (right).

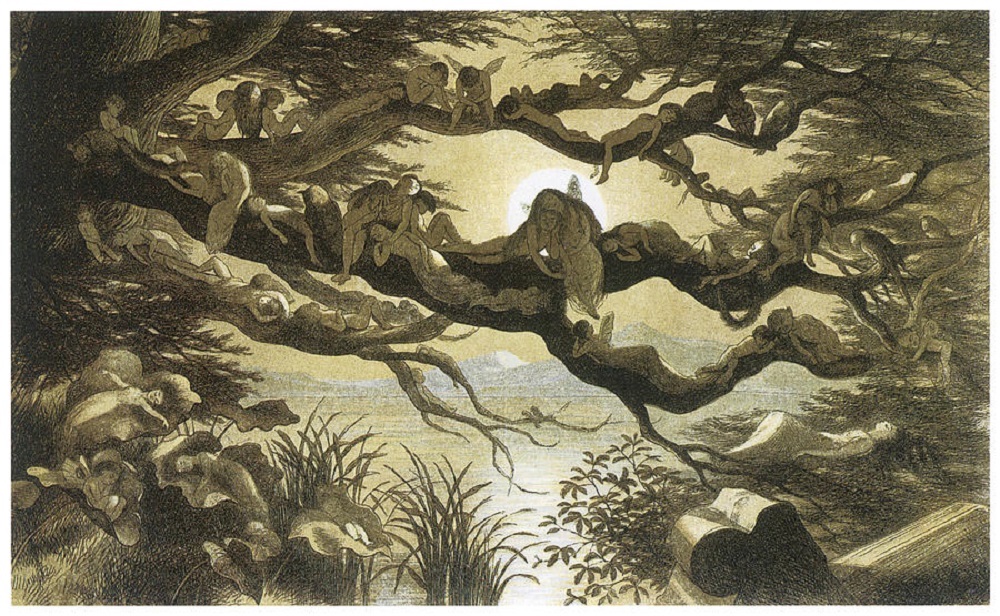

In his work for In Fairyland (1869–70), conversely, Doyle infuses the fairies with erotic feeling, using them to symbolize a sexual text that is only lightly encoded as they intermingle in sensuous proximity in Wood Elves at Play and Asleep in the Moonlight. In both cases, the fairies’ bodies are surrogates for real bodies, a scene which would never be shown directly without accusations of indecency.

Richard Doyle’s coded treatment of eroticism in the

form of fairy imagery in Asleep in the Moonlight.

Richard deployment of his symbolic language was parallelled, moreover, by Charles’s fairy imagery. Undoubtedly influenced by his brother’s extensive work, Charles presents an imaginative world in which the little people act, as they do in Richard’s illustrations, as symbols of mind and repressed feeling. In his Diary for example, Charles manipulates a sort of free-association technique, with images emerging and intermingling on the page as they give release, perhaps, to some of his constrained desires. In one page, we see figures shielding their eyes, juxtaposed to a figure riding a bucking horse; and in another a threatening, goblin-like figure creeps up on a group of fairies.

One of Charles Doyle’s menacing images in his asylum-diary.

The precise meaning of these images is impossible to determine, but their dynamism suggests that they act, in accordance with Freudian theory, to dispel the psychological energy generated by mental containment. Mapping a liminal space between reality and the imagination – as in Richard’s designs for In Fairyland – Charles also uses his brother’s dislocations of scale and space, so that his characters are quite literally in a spatial void, with apparently adult figures riding on the backs of birds or occupying the same domain as insects.

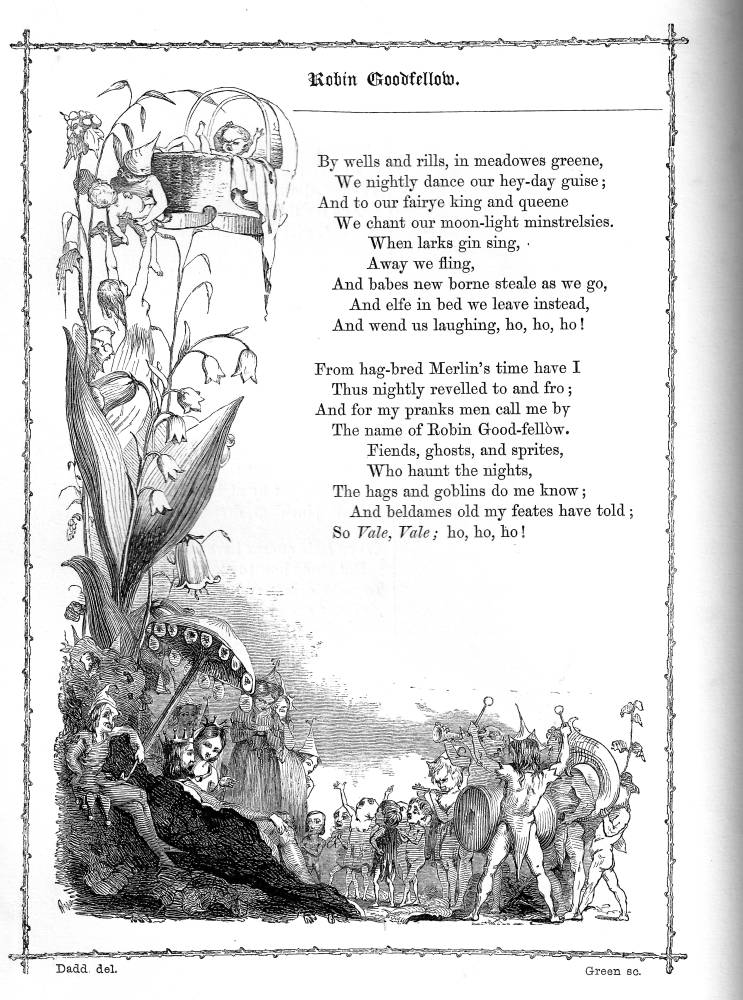

Richard Dadd’s illustration of Robin Goodfellow (1842).

The two brothers act in this sense to reinforce the familiar Victorian notion of fairyland as a symbol of madness or at least aberrant psychological conditions. Both Doyles were in common parlance, ‘away with the fairies,’ an Irish phrase they would surely have been familiar with. Their art recalls the paintings of Richard Dadd, the celebrated artist and patricide whose mania was enshrined, in the view of some critics, in paintings such as The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke (1855 –64, Tate Britain, London), and in his illustrations for The Book of British Ballads (1842). Charles Doyle’s designs certainly seem to bear a familial relationship with Dadd’s strange juxtapositions and incongruous changes of perspective and scale, the signs, perhaps, of mental illness.

Conan Doyle and the Cottingley Fairies

We can be certain that fairy imagery was associated with the irrational and the imaginative, offering a counter-cultural alternative to Victorian science and pragmatism. Like Pre-Raphaelite medievalism and classicism, the fairy world was a means of escape from the realities of everyday life, industrialism and the harsh economic facts of nineteenth century life. Indeed, at the end of the Victorian age there was a growing interest in the possibility that fairies were a tangible presence in folklore, an anthropological proposition developed by Andrew Lang and Sabine Baring-Gould and given an imaginative form in the fantasies of Arthur Machen.

Some believed the phenomenon might literally be real. The idea was enshrined in the famous case of the Cottingley Fairies, a mischievous hoax perpetrated by two children in the first quarter of the twentieth century – Frances Griffiths (aged 9) and Elsie Wright (16). The girls created their ludicrous and obviously-faked photographs by copying illustrations by Claude Arthur Shepperson from Princes Mary’s Gift Book (1914) and other at-hand materials; with understated but careful promotion by the parents, their images – which were only explained as forgeries when the perpetrators confessed to their deception in old age, following a lifetime of unabashed lying – became a world-wide sensation. What is astonishing is that Arthur Conan Doyle was one of the champions of the Cottingley cause, arguing in The Coming of the Fairies (1922) that the photographs were genuine.

Conan Doyle’s acceptance of the brazenly bogus is curiously at odds with his creation of the rationalist Sherlock Holmes, and in this connection his status as the son and nephew of a fairy artist must surely be significant. Having been familiar with such imagery from childhood, it seems as if he actively wanted his father’s and uncle’s imaginings to be real, no matter how implausible. Indeed, faced with the need to preserve his reputation as a man of science he had to work hard to justify his belief in the photographs: like Sherlock Holmes as he searched for a rational explanation of the (seemingly) supernatural dog inThe Hound of the Baskervilles (1902), he had to adopt what was ostensibly a scientific approach to his inquiries. In The Coming of the Fairies he claims his investigation was soberly objective, noting how he and others, including Arthur Gardner of the Theosophical Society, ‘had not proceeded with any undue rashness or credulity,’ and ‘had taken all commonsense steps to test the case’ (38). Yet Conan Doyle had been gulled by the children, their parents, and the deeply fraudulent Gardner, a process recounted at length in Joe Cooper’s recent study of the phenomenon.

The most famous of the Cottingley series, showing Frances looking at a paper cut-out of dancing fairies. The figures, with their Edwardian coiffeurs, were held in place with hair and hat pins.

His credulity is not so remarkable, however, when his other non-scientific interests are taken into account. A believer in Spiritualism and the occult and a participant at seances, his fascination with the fairies can be reframed as just another expression of his desire to find an alternative to a pragmatic reality, and here, once again, we can trace the influence of his family forebears. Richard and Charles’s development of fantastical dreamworlds is a constant in their illustrations and paintings, and Conan Doyle may also have been influenced by aspects of their imagery which goes beyond fairies and postulates a world of monsters and grotesques. Richard’s characterization of The King of the Golden River (1851) is a good example, along with his treatment of the dragon in Fortune’s Favourite (1849); Charles similarly offers many examples of incongruous monstrosity as exemplified by the The Giant and the Dwarf (1874).

Two of the Doyles’ treatments of fairy-tales: a) Richard’s illustration of The King of the Golden River (1851, revised ed.); b) the same artist’s Fortune’s Favourite (1849); and c) Charles’s The Giant and the Dwarf (1874).

All of these bogeys signify within the context of fairy-tales, but Conan Doyle refigures his grotesques within the narrative structures of supernatural stories and adventure narratives. In ‘Lot 249’ (Harper’s, 1892), he contemplates the fearful unknown, a symbol of foreign otherness, in the form of the malignant mummy; and in The Lost World (1912) he takes the reader into a plausible alternative world in which dinosaurs have survived.

A fantasist despite – or perhaps because – of his obsession with the pragmatism of Holmes and the idea of a purely materialistic, legible world, Conan Doyle projects the imaginative mindset of the Doyles, and was the natural heir to a dynasty of complex and multifaceted artists who produced a distinctive body of work as they negotiated a series of themes, ideas, and preoccupations.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Allingham, William. In Fairyland. Illustrated by Richard Doyle. London: Longmans, 1870 [1869].

Baker, Michael. The Doyle Diary. London: Paddington Press, 1978.

The Book of British Ballads. London: Jeremia Howe, 1842 [Richard Dadd illustrations].

Conan Doyle, Arthur. The Hound of the Baskervilles. London: George Newnes, 1902.

Conan Doyle, Arthur. The Lost World. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1912.

Conan Doyle, Arthur. ‘Lot 249.’Harper’s Magazine (1892).

Cusack, Mary Frances. An Illustrated History of Ireland from AD 400 to 1800 [Henry Doyle illustrations]. New York: Catholic Publications Society, 1868.

Doyle, James. A Chronicle of England, B.C. 55 – A.D. 1485. London: Longman, Green, Longman, 1864.

Doyle, Richard. Bird's Eye Views of Society. London: Smith Elder, 1864. First published in The Cornhill Magazine, 1863–4.

Doyle, Richard. Dick Doyle’s Journal. London: Smith Elder, 1885.

Doyle, Richard. The Foreign Tour of Messrs. Brown, Jones, & Robinson. . London: Bradbury & Evans, 1855.

Doyle, Richard. Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

Doyle, Richard. Scenes of English History. London: Pall Mall gazette, 1886.

Doyle, Richard. The Tournament. London: Dickinson, 1840.

Lemon, Mark. The Enchanted Doll. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

London Society, 1862–3 [Charles Doyle illustrations].

Montalba, Anthony [Whitehill, Anthony]. Fairy Tales from all Nations. London: Chapman & Hall, 1849.

Princess Mary’s Gift Book. London: Stodder & Houghton, 1914.

Punch. 1843–1850 [Richard Doyle illustrations].

Roses and Holly. Edinburgh: Nimmo, 1867, 1874. [Charles Doyle illustrations].

Ruskin, John. The King of the Golden River. London: Smith Elder, 1851 [Richard Doyle illustrations].

Titmarsh, M. A. [Thackeray, W. M.]. Rebecca and Rowena. [Richard Doyle illustrations].London: Chapman & Hall, 1849.

Wharton, Grace and Philip. The Queens of Society. New York: Harper, 1860 [Charles Doyle illustrations]

Secondary Sources

Conan Doyle, Arthur. The Coming of the Fairies. New York; Doran, 1922.

Cooper, Joe. The Case of the Cottingley Fairies. London: Robert Hale, 1990.

Created 18 December 2023