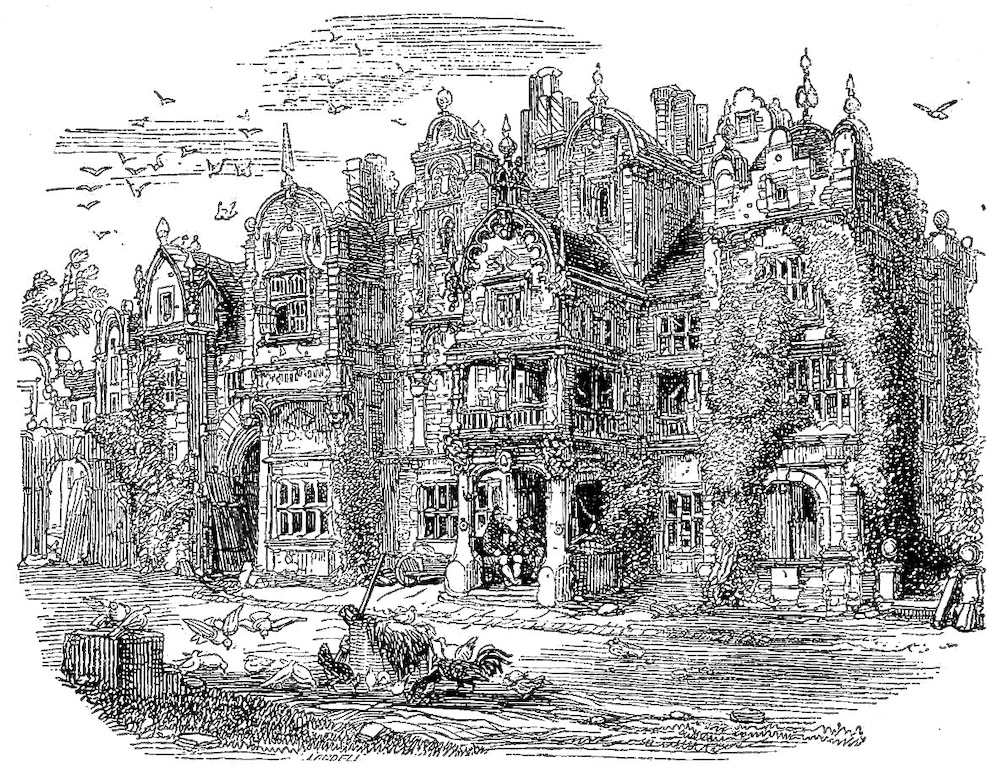

The Maypole by George Cattermole. 3 ½ x 4 ½ inches (8.7 cm by 11.3 cm). Vignetted wood-engraving. Chapter 1, Barnaby Rudge. 13 February 1841 in serial publication (first plate in the series). Part 1 in the novel, serialised in Master Humphrey's Clock, Vol. 3 (part 42), 229. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: An Ornate Facade

IN the year 1775, there stood upon the borders of Epping Forest, at a distance of about twelve miles from London — measuring from the Standard in Cornhill, or rather from the spot on or near to which the Standard used to be in days of yore — a house of public entertainment called the Maypole; which fact was demonstrated to all such travellers as could neither read nor write (and at that time a vast number both of travellers and stay-at-homes were in this condition) by the emblem reared on the roadside over against the house, which, if not of those goodly proportions that Maypoles were wont to present in olden times, was a fair young ash, thirty feet in height, and straight as any arrow that ever English yeoman drew.

The Maypole — by which term from henceforth is meant the house, and not its sign — the Maypole was an old building, with more gable ends than a lazy man would care to count on a sunny day; huge zig-zag chimneys, out of which it seemed as though even smoke could not choose but come in more than naturally fantastic shapes, imparted to it in its tortuous progress; and vast stables, gloomy, ruinous, and empty. The place was said to have been built in the days of King Henry the Eighth; and there was a legend, not only that Queen Elizabeth had slept there one night while upon a hunting excursion, to wit, in a certain oak-panelled room with a deep bay window, but that next morning, while standing on a mounting block before the door with one foot in the stirrup, the virgin monarch had then and there boxed and cuffed an unlucky page for some neglect of duty. [Master's Humphrey's Clock, Chapter the First, 229-30]

Commentary: The Maypole sets the Keynote

Cattermole's alternate design of the headpiece for chapter one,

Dickens had set his previous novel, The Old Curiosity Shop, back just a generation, so that it becomes a "Condition of England" Novel by comparing the old-fashioned usages of the country, the dubious business practices of the new society of the metropolis, and the poverty, desperation, and rebelliousness of the Dark Country. Now, the writer undertakes a second full-length novel in the same journal, Master Humphrey's Clock, to keep the periodical afloat. But this time Dickens is emphatically setting the story's action back almost half-a-century to examine some of the same societal tensions that he explored in the first. To announce this more distant temporal setting Dickens has had Cattermole depict a traditional inn on the outskirts of London, far enough away from Cornhill to be rural, but close enough for the actors who make their debuts at the Warren and the Maypole to make their way conveniently to the capital. By associating the vast and gloomy inn with the age of Elizabeth Dickens has cued his artist to produced something elaborate, ornate, and outlandish to nineteenth-century readers.

And, of course, this was just the sort of architectural set at which the antiquarian illustrator would excel, as Dickens knew from Cattermole's drawings of Little Nell's sugarloaf cottage in the old cathedral town, Kit darted off, the birdcage in his hand, towards the spot where the light was shining in the parsonage (exterior), and At Rest (Nell dead) (interior) in the concluding instalments of The Old Curiosity Shop. Jane Rabb Cohen (1980) regards Cattermole's contributions to the second novel as an extension of his work for the first:

Meanwhile, Master Humphrey's Clock ran on, and Barnaby Rudge succeeded The Old Curiosity Shop, making its public appearance on February 13, 1841. The historical fiction, set, like Scott's best novels, fifty years earlier than it was written, offered a wealth of congenial subjects for the antiquarian painter. Dickens assigned Browne the individual characters and crowd scenes, and Cattermole all the picturesque structures. The old edifices Dickens imagined for The Old Curiosity Shop, all redolent of decay and death, are memorable only collectively. By contrast, his structures in Barnaby — the Maypole Inn (fig. 126), the Locksmith's house, the Boot, the Warren (fig. 127), and Westminster Hall (see fig. 62) — function dramatically and distinctively throughout. The buildings acquire a status almost like that of characters. Cattermole warmed to the tasks so perfectly suited to his tastes. His complex curlicues, if not historically accurate, are extremely nostalgic. [131]

Dickens continued to treat Cattermole with kid gloves, regardless of the merit of his work, perhaps partly out of sympathy for the artist's increasing harassment due to illness, impending fatherhood, debt, and other commissions. When the artist drew the ornate, multigabled Maypole Inn for the opening scene (1,1) (fig. 126), the author claimed that he was unable to bear the thought of its being cut on the block, and wished he could "frame and glaze it in statu quo forever and ever. In Cattermole's hands, he maintained, the scene of Chester warming himself before the Maypole's finest fireplace (X, 84) (see fig. 54) would be "a very pretty one." Dickens was especially helpful to Cattermole, now copying his own drawings onto the wood, in tangible ways as well. He exerted himself to procure a long block so that the Locksmith's house might "come upright, as it were," and when this subject, meant for chapter 7, was not executed until chapter 16 (XVI, 134), Dickens remained uncharacteristically patient, trusting that Cattermole's delineation of the "shy blinking" house with the conical roof would be worth the delay (IV, 33-34). [132]

The Text and the Complementary Headpiece (13 February 1841)

Phiz's ornamental "I" vignette-letter marks the opening of what was the

novel's first monthly instalment:

Dickens begins by pointing out the general lack of literacy in the 18th century, undoubtedly a concern for a writer addressing a mass market in an eighteenth-century-style periodical such as Master Humphrey's Clock. He invokes the names of Henry VIII and Elizabeth in describing the history of Tudor inn. Dickens presents a detailed description of the building, perhaps in part as a guide to his "architectural" illustrator, George Cattermole, and in part to present the taproom as a complement to the headnote illustration of the fanciful exterior with no less than seven gable-ends, half-a-dozen composite, leaded-pane windows, and two small figures in the main portico:

Its windows were old diamond-pane lattices, its floors were sunken and uneven, its ceilings blackened by the hand of time, and heavy with massive beams. Over the doorway was an ancient porch, quaintly and grotesquely carved; and here on summer evenings the more favoured customers smoked and drank—ay, and sang many a good song too, sometimes — reposing on two grim-looking high-backed settles, which, like the twin dragons of some fairy tale, guarded the entrance to the mansion. [230]

The illustrator emphasizes the presence of many examples of native bird species, both in the air and on the ground, again reflecting Dickens's description of the building: "In the chimneys of the disused rooms, swallows had built their nests for many a long year, and from earliest spring to latest autumn whole colonies of sparrows chirped and twittered in the eaves. There were more pigeons about the dreary stable-yard and out-buildings than anybody but the landlord could reckon up. The wheeling and circling flights of runts, fantails, tumblers, and pouters, were perhaps not quite consistent with the grave and sober character of the building" (230). That it seems, despite the vigour of its avian patrons, to be dozing may reflect Dickens's attitude to the whole century, which seemed to Dickens to have lacked Victorian energy, innovation, and technology: "the old house looked as if it were nodding in its sleep. Indeed, it needed no very great stretch of fancy to detect in it other resemblances to humanity." (230). Decaying, discoloured, and time-worn, The Maypole represents the stiffling effects of a long, unalloyed tradition. Cattermole certainly creates visualisations of such aspects of the textual description as "the sturdy timbers had decayed like teeth" (230), but imbues the elaborate facade with the enchanting architectural detailism one might find in a children's story's narrator's description of a witch's gingerbread house. And that is the element that Cattermole adds to Dickens's description: antiquated charm.

One receives little sense of the windy, rainy March evening upon which the novel opens. Since John Willet, the publican, is inside at the moment Dickens takes up the story, he is not likely to be one of the figures in the centre of the composition: these are mere artistic license on Cattermole's part, and he fails to suggest the nocturnal setting that Dickens describes: "The moon is past the full, and she rises at nine" (231).

Hammerton in his preface to the 1841 illustrations for the novel notes that neither the published nor the alternate design of The Maypole bear any resemblance to the actual inn opposite the Chigwell churchyard, for each "is entirely a work of fancy" (213). Dickens nevertheless endorsed the illustration as beautiful and moving when he previewed the actual pencil drawing: "Words cannot say how good it is. I can't bear the thought of its being cut, and should like to frame and glaze it in statu quo for ever and ever" ("Dickens to Cattermole," 9 Feb. 1841, cited in Hammerton, 213, and in Kitton, 127).

Related Scene from the Phiz Sequence: Chapter I

- An Unsociable Stranger (Vol. II, 233)

Related Material including Other Illustrated Editions of Barnaby Rudge

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- George Cattermole, 1800-1868; A Brief Biography

- Phiz's Original Serial Illustrations (1841)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First Illustrators — A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's six illustrations (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s ten Diamond Edition illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 46 illustrations for the Household Edition (1874)

- A. H. Buckland's 6 illustrations for the Collins' Clear-type Pocket Edition (1900)

- Harry Furniss's 28 illustrations for The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image and text by George P. Landow, with additional commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Chapter Five: George Cattermole." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. 125-134.

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XIV. Barnaby Rudge." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition, illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. 213-55.

Kitton, Frederic George. "George Cattermole." Charles Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition. 121-135.

Vann, J. Don. "Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock, 13 February 1841-27 November 1841." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. 65-6.

Created 4 January 2006

Last modified 26 December 2020