[The following essay has been transcribed from the Internet Archive version of a copy of the 1897 Magazine of Art in the University of Toronto Library. Links take you to material in the Victorian Web. Click on images to enlarge them. — George P. Landow.]

f there is one sign more encouraging than another of the awakening to the fuller, the more universal, appreciation of art in these later days, it is to he found in the wider practice of its various methods of expression adopted” by certain of our artists, after the manner of the great Italians. I do not mean versatility alone, like that of which Professor Herkomer is so hrilliant an example, nor the dual majesty fur draughtsmanship and modelling that have distinguished Mr. Watts, Lord Leighton, Mr. Birch, Sir Edward Poynter, and others of repute. I mean rather the need felt by the artist for expressing himself in such ways as the various resources of art give him opportunity for. This we see in different degrees in the case of William Morris and Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Mr. Voysey, Mr. Anning Bell, and Mr. Walter Crane — whose aim, it appears to me, is not such as we generally find, merely to produce works in painting and in sculpture and what not; but, having some thought to express, to seize the most appropriate means afforded” by art for the realisation of the particular intention of the moment. Representative in a high degree among these, so to say, polyglot artists is Mr. W. Reynolds-Stephens, whose short but hitherto brilliant career receives notice in these pages, not only in virtue of the merit of his past achievements but” by the interest of his varied ability as painter, sculptor, designer, and art craftsman.

I well remember the prize-giving in 1857, when after listening to Leighton's discourse on the Italian Renaissance, and on the genius of Michael Angelo, whose supreme power in many arts inspired his warmest rhetoric, I passed on to examine the works of the youth who had that year distinguished himself — the merest student in the wake (of a great master —” by carrying off prizes for both sculpture and design. The subject of the former was "Summer;" the latter, the Landseer Scholarship for set of figures from the life. Both works were promise of such equal merit that one could hardly guess in which art he was the most proficient or which would ultimately claim his exclusive devotion. As the event turned out, he has remained true to both sculpture and painting: but if one art more than the other calls forth his rarer powers, it is, I think, withdut a doubt, that form of decorative sculpture which gives full play at once to his originality, his imaginative fancy, and his passion for design.

His early youth was not passed as is that of most boys. Born in 1862, of English parents, in Detroit, he received his earliest impressions in Canada. His subsequent school life was divided between England and Germany, and his training was for the profession of engineering. When his majority permitted him to choose for himself, he threw up a promising position for the sake of art. and in 1884 entered the Royal Academy schools. He was still a student when, in 1885, he sent his first contribution to the Royal Academy exhibition; and from that lime forward he has been regularly represented there in the sections either of painting or sculpture, and at times of both.

Summer

On leaving the schools he had carried off the prize for a design for the decoration of a public building. This was his very striking wall-picture entitled 'Summer," a work in design and arrangement, in suavity and harmony of line, that would not have done discredit to such masters as Leighton and Albert Moore, had they been content with the rather obvious arrangement of the composition. This work is singularly successful; it is full of grace and harmony; the languor and the brightness of Summer are reflected and felicitously suggested in the graceful poses and ingenious arrangement of these five beautiful maidens, neither too realistic nor too purely decorative. There is an actuality and a humanity about the design which relieve it of all stiffness and cold formality, yet saving it at the same time from the charge of being too pictorial. The exact balance of the figures, in spite of differences of detail as well as of colour, the ingenuous conventionality in the treatment of the carpet, the just formality of the architectural symmetry, were adopted with courage and worked out with triumph. The decorative faculty of the artist is not less strikingly shown as well in the details as in the general composition; indeed, so much care does the artist appear to have lavished on his design that he has found in the wall-fountain on the right of the picture a motive for one of his most graceful sculptural works, of which I shall have to speak later on.

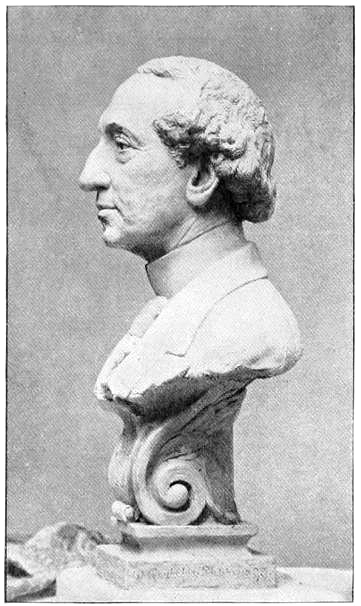

Self-portrait by William Reynolds-Stephens.

This design of "Summer "was so highly approved” by the President and Council of the Academy that the commission to carry it out on the wall of the refreshment room m that institution was, as a special act of grace, awarded to the young artist. I have examined his work quite recently, and regret to find that so notable a picture promises to stand ill the effects of time. This is probably not so much the fault of the climate as of the authorities of the Academy itself, who have actually allowed a heating-apparatus to remain immediately under the picture, and on either side a huge ventilator. All the floating dirt in the room is carried along” by the mechanically-produced draught to the surface of the picture, darkening its surface, and the severe cleanings that have been necessitated in consequence appear to have left little but the underpainting. [Footnote: I understand that a formal protest on the subject has been made to the Academy, but that no remedy appears to have been determined on.] It is not likely, however, that the design will be completely lost, for the artist repeated his picture upon canvas, and with it won an honourable mention in the Salon of 1892 and the gold medal at the Califonian Exhibition of 1894. I must admit that I care less for this large picture than I do for the wall-painting, either in point of colour or of execution. The artist appears to have been at that time somewhat cramped in the use of oils upon canvas beside the more virile delights of mural painting, even though he use the same mediums and materials; and there is some lack of spirit about the touch, notwithstanding the general beauty of the work. As a youthful production, it is a remarkable one, justifying, I believe, those who watch the progress of art in anticipating for its young author a very considerable place in the ranks of his country's workers.

Mr. Reynolds-Stephens' success in sculpture had not escaped the watchful eye of Mr. Alma-Tadema — a painter who takes delight in giving encouragement to the young knights of his order. Mr. Alma-Tadema set before Mr. Reynolds-Stephens a difficult task — some might think, artistically considered, an illegitimate one. His famous picture of "The Women of Amphissa" had drawn forth general applause, and it occurred to him to commission the young sculptor to reproduce it as far as possible in relief, so that it might form a frieze for his studio. The limits of sculpture are so clearly defined that the translation of a purely pictorial scheme into sculpture was a matter to test not only the ability but the tact and taste of the young artist. Difficulties, however, were ingeniously overcome, and the principal groups as well as the motif of the picture were reproduced in a relief wrought in copper in a panel 18 feet long” by 18 inches high. It was completed in 1889, and was exhibited at the Royal Academy in the same year. In 1890 — working in metal still occupying his attention — Mr. Reynolds-Stephens wrought and exhibited the wall-fountain of which he had made the design, already alluded to, in his picture of "Summer," merely adding drapery to the figure of the water-nymph who rises above the stream that juts forth beneath her feet. This work, as may be seen, is of singular grace; it is of further interest as striking the first note in harmony with the aims of the Arts and Crafts [Movement] with which the artist was soon to be closely associated.

Pleasure

Next followed his picture called "Pleasure," exhibited at the Academy in 1892. The suggestion may be an unjust one, but it appears to me that neither then nor in the following year, when "Love and Fate" was exhibited, Mr. Reynolds-Stephens had wholly thrown off his recollection of other painters and become, as he has since become, entirely original. In "Summer," as I have said, we seem to feel the influence of Albert Moore; in "Pleasure" the motif recalls the allegorical treatment with which Etty, among English painters, mine than once handled a similar subject; and in "Love and Fate" there is an Alma-Tademesque reminiscence, dominated however,” by a classic divinity which in dignity and elegance of composition was all Mr. Reynolds-Stephens' own — so far as the influence exercised on him” by Mr. Alfred Gilbert would allow.

In the Arms of Morpheus

The year 1894 brought forth the pleasing work entitled "In the Arms of Morpheus," in which the suave lines of the composition strike the spectator not more than the elegance of the treatment. And in the same year, as if to prove his versatility, he produced the portrait of " Mrs. Eiloart" — a portrait bien posé, felicitously arranged, and full of dignity; a work that would have justified the artist in selecting the more lucrative profession of portrait-painter, had he not conceived a higher aim for his artistic career to which he has adhered with characteristic devotion.

Left: John Dando Sedding's Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Street, London SW1. Right: All Men Seek Thee. Altar frontal in Lady Chapel, Holy Trinity Church. Articles in both the 1897 Magazine of Art and the 1899 Studio call it The Nineteenth-Century Worship of Christ. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

A new line was struck out” by the artist when, for an altar-front in the late Mr. Sedding's Holy Trinity Church in Sloane Street, Mr. Reynolds-Stephens designed the work which, never publicly exhibited, is here reproduced. This is the religious symbolical painting representing "Nineteenth Century Worship of Christ." The idea of submission to some higher power” by carefully differentiated types of humanity has before now been adopted” by various artists, notably” by Mr. Watts in his "Court of Death;" but the application to its subject in the present instance is, so far as I am aware, an original one. The adoration here shown is of modern Society, in place of the familiar and altogether superior Magi; the child and the old man, the lady, the peasants, and the guardsman are types, as near as need be, of the people of to-day; and the Mother and Babe, with the celestial choir,” by their felicitous arrangement, make harmony of hat might easily have been dangerously near to incongruity. The scheme of colour does not appeal o me personally, but the certainty with which the painter has struck the appointed note of feeling, and the equal ease which he has once more composed is picture in pleasing lines, constitute a strong claim for the canvas to be reckoned seriously when the talent of the artist is analysed.

Left: Happy in Beauty, Life, and Love, and Everything. Middle: The Sleeping Beauty. Right: Sir John Macdonald

In sculpture Mr. Reynolds-Stepliens has covered a field still wider than that in painting, and, as has already been said, has aimed at decoration as its dominant note. Even in a portrait bust such as that of Sir John Macdonald, he has successfully sought in the device of the scroll some means whereby to relief the conventional pedestal of its usual ugly formlessness. The treatment of the strong head is good and elaborately modelled, and though it is, to some extent, what might be called painter's sculpture, it is on that account, perhaps, the more picturesque and the more interesting and resembling.

One of the artist's principal merits, not altogether unconnected perhaps with his training in one of the exact professions, is the skill with which he adapts sculpture to architecture, keeping it in proper proportion and in its proper place as an embellishment of the main work. His high relief of "Truth and Justice" executed for the portal of the London and County Bank in Croydon fills its purpose with great charm. Symbolical though they are, the two figures are entirely modern in treatment; Truth represented as a young girl writing upon an open scroll, and Justice as a nude boy, blindfolded, holding up the scales before her. There is novelty in the arrangement, and thought too; but for my own part I believe that the nobler conception of emblematic justice is the representation of the divinity with eyes unbandaged.

A work of extraordinary sweetness and skill was exhibited at the Academy of 1896, under the title of "Happy in Beauty, Life, and Love, and Everything," a portrait in low relief of a quaintly, daintily clad young girl of singular beauty who looks out to the spectator, while her reflection,” by a poetic licence, is shown mirrored in half-profile behind her. Charming as it is, with dainty outline, freshness, and grace, it is not more pleasing than the coloured gesso taken from it, or the studies in chalk and colour that helped in its execution. Finally there is the beautiful relief recently completed to till the space beneath an overmantel on the subject of "The Sleeping Beauty." [Footnote: It should be said at once that the reproduction, is good as can be from a photograph, does no sort of justice to the beauty of the original.] The work is much less suggestive of that of Burne-Jones than appears from the illustration, and it is far fuller of thought and invention than there is any means of indicating, Against a background of thick briar rose — for the growth, it: will be remembered, was of ancient date — stands the window seat whereon the princess lies attended” by her slumbering maids. The prince, young, and of manly beauty, stoops to imprint the kiss of deliverance. His dress is embroidered with cupids; the princess's robe with hearts and sweet pea clinging; textures throughout are suggested with curious success — muslin, satin, and stamped velvet; and the partitions of the seat are crowned — a happy thought — with poppy heads. The design supports and follows carefully the architectural lines; and there are many passages in the figures of singular charm and beauty. The mention of this work and a highly-studied bronze head admirably cast” by cire perdu: lirings to a, conclusion the more important works in sculpture of Mr. Reynolds-Stephens.

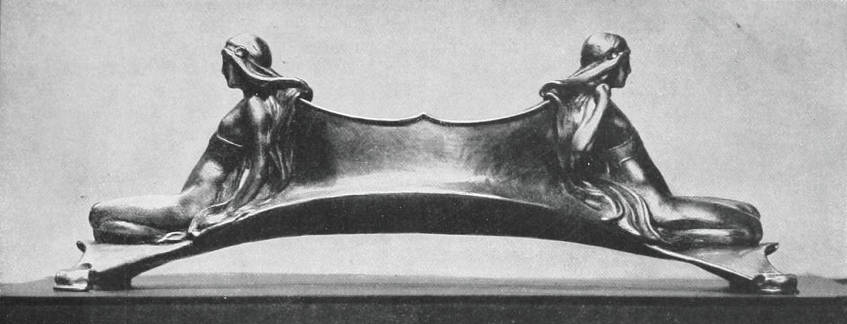

Silver Bonbonière.

There remain to be considered his works in design associated with his labour in the Arts and Crafts. Of these the most valuable are those in metal. The artist has devoted more attention than any with whom I am acquainted, except perhaps Mr. Alfred Gilbert, to the subject of alloys and above all of patina. This branch of art-craftsmanship is not, generally speaking, an object of an artist's innnediate personal concern. At least, his anxiety is usually of the platonic sort and rarely goes farther than the appeal to the founder to produce such effects of surface as he wishes to obtain. Mr. Reynolds-Stephens has studied the subject at first hand, and for his smaller works has made numerous experiments with a view to obtain the quality and colour that he desires; the study, of course, is a fascinating though perhaps hardly a remunerative one; and the delights of accident are hardly less than the delights of calculated effects. The science of alloying, the questions of metals and of temperatures, can yield results as exquisite to those who can appreciate them as the greater qualities of silhouette and form. The result of his earliest labours in this direction are to be seen in a metal photograph-frame singularly pleasing in design though lacking somewhat in subtlety, as youthful work is apt to be. Far better is the masterly letter-box front which has already appeared in these pages. A silver sweetmeat dish made to lift and hand round, of ingenious ornament and Gilbertian fancy, demonstrates how, even in these days of murky nineteenth-century life, there are artists able and willing still to invent articles of a domestic use and invest them with beauty of a kind which was enjoyed in the halcyon days of Florentine splendour.

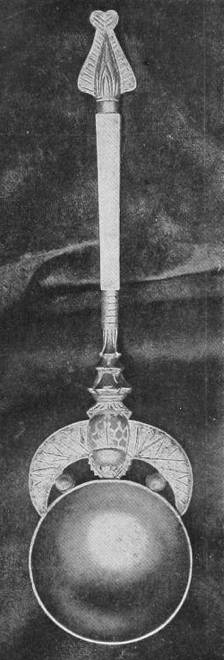

Left: Silver, ivory, and enamel Spoon. Right: Embroidered dress front.

That Mr. Reynolds-Stephens' fancy does not stop here, his serving-spoon of Egyptian design can show. It is of silver, ivory, and enamel, and breaks ground in another direction. In yet another section of art, the dress-front given on page 74 illustrates a knowledge of effect rarely shown” by needlework designers. The ground is of palish green silk, the pattern of extremely intricate and fanciful design composed of sweeping lines and curves that intersect and reintersect each other, and is embroidered (by Mrs. Reynolds-Stephens) with white floss-silk in such a way that the stitchery catches the slanting lights according to their angle and produces an effect fascinating out of all proportion to the simplicity of the means and the materials employed.

Versatility has ruined more artists than it has made, and is more often the expression of a wayward artistic nature than a proof of universality of genius. Mr. Reynolds-Stephens' talent is so equally balanced that it is hard to say that” by devoting himself to any one style of art lie does injustice to his ability in any other. He is no prouder of the term of artist than of that of craftsman; his view of art is sane, and though enthusiastic, full of calm resolution. He is rising to a front rank, and his advance to that point it will be a matter of interest to watch.

Bibliography

Spielmann, M. H. “Our Rising Artists: Mr. W. Reynolds-Stephens.” Magazine of Art. 21 (June 1897): 71-77. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 23 October 2014.

Last modified 25 October 2014