Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

In transcribing the following article I have followed the invaluable text off the Hathi Trust online version. The portrait of Linton and illuminated W, which I have coored red, come from the original article. — George P. Landow .

ILLIAM JAMES LINTON was born in London in 1812. Having natural artistic proclivities, he was apprenticed in his sixteenth year to G. W. Bonner, " a nephew and pupil of Branston, and a good artist,” as Mr. Linton has since said of him, and certainly one of the best wood-engravers of that time. It is a fact worthy of record that the first year of his apprenticeship — 1828 – is coincident with that in which died Thomas Bewick, the restorer of the art of wood-engraving in England; the life-work of the one began directly that of the other had concluded. On whom could the mantle of the great Novocastrian artist more fittingly descend than upon the subject of the present monograph?

William James Linton, Engraver and Poet Poet. Engraved by W. Boscombe Gardner. Click on image to enlarge it.

Specimens of Mr. Linton’s earliest work are to be found in Martin and Westall’s Pictorial Illustrations of the Bible (1833), to which publication Jackson, Branston, Landells, Powis, T. Williams, and other clever engravers contributed. Linton, who had then hardly concluded his term of apprenticeship, here indicates his early ability as a wood-engraver; in fact, these woodcuts, for minuteness and artistic com pleteness, cannot be excelled. At the expiration of his apprenticeship in 1834 he worked for a year with Powis, and then during a year or more for Thompson; after that he was employed on such publications as the Heads of the People, Shakespeare and Cowper, and on landscape foregrounds. Indeed, his talent soon brought him many important commissions, among others that of engraving many of the illustrations for the Book of British Ballads (1842), the drawings by his early friend W. B. Scott, Franklin, Kenny Meadows, and other well-known designers. In 1842, Mr. Linton became the partner of John Orrin Smith, another prominent engraver, of whom Horace Harral had been a pupil, and, moreover, a pupil privileged to work daily beside Mr. Linton. [Note: Mr. Orrin Smith excelled in the depictions of animals and landscape, and, it is said, to have no rival in conveying the idea of space and distance by a skillful managed tone.]

In that same year that flourishing journal, the Illustrated London News, first saw the light, and it was only natural that the enterprising projectors, desirous of concentrating upon it the best available talent, should endeavour to secure the services of Mr. Linton and his partner. In this they succeeded, although the names of the two engravers do not appear (so far as I can discover) until the publication of the second volume in the following year, when I find them appended to what I believe to be the first of a long series of woodcuts which, invested with the artistic talent of Mr. Linton, continued for many years to adorn the pages of the London News. This picture — a fanciful design by William Harvey (Bewick’s favourite pupil), who gave up engraving in favour of drawing — is entitled A May Garland; and a few weeks afterwards Messrs. Smith and Linton’s first landscape appeared — a View of Hampton Court Palace. Their partnership was of short duration, however, for in 1843 Mr. Orrin Smith died suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving Mr. Linton in sole charge of a business on which two families depended; and for this reason we find Mr. Linton’s name only as engraver in the London News of the Queen’s visit to the Midland Counties in that year.

In 1844 the London News published a series of papers on “Wood-Engraving: its History and Practice,” written by William Andrew Chatto. [Note: Published separately in 1848. Ten years previously Mr. Chatto and Mr. John Jackson published a comprehensive Treatise on Wood-Engraving, which has hitherto been considered as a text-book by engravers.] To Messrs. Smith and Linton the superintendence of the drawing and engraving of the cuts for this article were intrusted, but owing to the death of the former before they were finished, their completion devolved entirely upon Mr. Linton. As these were given as characteristic examples of modern engraving, it was obviously a well-merited compliment to Mr. Linton in selecting him for the work; they were considered at the time as the best specimens of wood-engraving of their kind that had ever been printed by means of a steam-press. In 1847, Mr. Linton is again to the fore with work for the London News. Besides several subjects relating to sea-fishing (of which Mackerel Fishing is decidedly the best), many pages were devoted to scenes in Shakespeare’s County, and the illustrations that were engraved by him bear not only his name but the unmistakable impress of his hand.

The size and number of the cuts in the London News called for new talent in drawing, giving occasion for fresh endeavours in engraving. At first Harvey stood alone as draughtsman, but now the proprietors of the paper obtained drawings from some of the best painters in water-colour — W. L. Leitch, Duncan, Dodgson, and others — whose work upon wood, as Mr. Linton says, marks an era in wood-engraving. Besides the artists already named, the admirable work of Lance, Sam. Read, and the copies of Turner’s pictures must be mentioned, these lending themselves most appropriately to Mr. Linton’s style of engraving. The most important of the series are Rembrandt’s Descent from the Cross (1854), Flowers and Fruit, by Lance (1855), The Ivory Carver, by Wehnert (1857), Coming Events cast their Shadows before (1863) and Under a Cloud (1866), both by Read, and Mr. Linton’s rendering of these subjects is remarkably effective and artistic.

A peculiarity in the treatment of the last subject is that the engraved lines are horizontal, as befits the mysterious effect of the subject, the difference of tone being obtained by a variation in their thickness — a noticeable feature in many of Mr. Linton’s engravings of pictures, as for example in Turner’s Snowstorm on Mont Cenis (1865), The Fall of Reichenbach (1865), A Stackyard (from the Liber Studiorium), Queen Mab’s Grotto, and A First-Rate taking in Stores (1865), all of which are admirable, and sufficiently illustrate the true artistic knowledge of the engraver. Among the later works for the London News which Mr. Linton claims as being entirely the work of his graver are the Peacock at Home and Dead Birds, drawn by Archer after pictures by Lance, and The Old Mill and The Ferry, on the wood by Duncan and Dodgson respectively, all of which are printed (with that justice due to magnificent work) in Mr. Linton’s latest book on the subject of engraving (hereafter described), where he with all modesty says: — “However unsuccessful, I yet may claim the distinction of ordering the whole toward the revival of white line,” the intelligent graver-work of the Bewick School. These various engravings by many draftsmen afforded an excellent field of practice such as had not previously been available. Boldly treated, as was necessary for the rapid production of a newspaper, they were a healthy change from the then prevailing tameness. "

It must not be imagined that Mr. Linton’s time was monopolized by the commissions he received from the London News; on the contrary, his ever-busy graver was at the same time engaged upon work for various illustrated publications in which a cut by Linton added so much to the “artistic merit.” It would be difficult, if not impossible, to enumerate all the woodcuts which he has produced during a long career, but I must mention those delightful little vignettes in Dickens’s Christmas Carol (1843), drawn by John Leech (what a talented trio – Dickens, Leech, Linton!); [Note: Mr. Linton also engraved Leech’s illustrations for Dickens’s second Christmas book, The Chimes, and the artist was evidently so pleased with these reproductions of his drawings that, in a letter to Mr. Forster (dated Nov. 18, 1846), he added this postscript: “I should like, if there is no objection, that Linton shoull engrave for me. " This had reference to the illustrations for The Battle of Life (Dickens’s fourth Christmas stoy), but for some reason the work of engraving was entrusted to others.

In the following works he is well represented — Milton’sL’Allegro (circa 1851), Favourite English Poems (1859), The Merrie Days of England (1859), Pictorial Tour of the Thames, Burns’s Poems and Songs, Shakespeare: his Birthplace and Neighbourhood (1861), The New Forest (sixty three illustrations by Walter Crane, 1863), etc., etc.

In 1849 Mr. Linton visited Cumberland, shortly afterwards taking up his residence at Brantwood by Coniston Water, and occupying the very house which is now the home of John Ruskin. Here, in 1854, he wrote a little book on The Ferns of the English Lake Country, with woodcut illustrations by himself: four years later he married the youngest daughter of the late Rev. J. Lynn, vicar of Crosthwaite — a lady [Eliza Lynn Linton] whose literary work is so familiar to us. [Note: It should be noted that Miss Lynn is Mr. Linton’s second wiſe, he having previously married a lady by whom he has several children. And it is interesting to add that Miss Lynn at one time resided with her father at Gad’s Hill, in the very house where Charles Dickens lived and died.

In 1858 a small volume was published on The English Lakes, by Harriet Martineau, with woodcuts by W. J. Linton, who also superintended the printing of the blocks, the impressions being taken on India paper; and although some of these cuts are mere “thumbnail” sketches, they are invested with considerable artistic feeling. In 1864 there appeared another work of the same character, entitled The Lake Country, in which husband and wife co-operated, the text being by Mrs. E. Lynn Linton; and the hundred illustrations, drawn and engraved by Mr. Linton for this book, speaking generally, are decidedly more pleasing than the first series. One of the most satisfactory cuts is that of Rydal Water-a perfect picture in a space of eight square inches!

Rydal Water, drawn and engraved by by W. J.Lindon. (From The Lake Country by permissin of Messrs. Smith, Elder,and Co.

In 1859 an illustrated edition of Milton’s L'Allegro was produced, with en gravings on wood by Mr. Linton, copied from the etchings (published some ten years previous. by Bewick, Horsley, and other members of the Etching Club. To this period also belongs another important venture, namely, the publication of Thirty Pictures of Deceased British Artists (1860), expressly engraved by Mr. Linton for the Art Union of London. These exhibit the engraver at his prime, and nothing could possibly be finer than the exquisite rendering of this series, which includes characteristic examples of Sir T. Lawrence, Constable, Gainsborough, Sir J. Reynolds, Wilkie, Blake, Bonington, Hogarth, Morland, Turner, and other masters of the English School of Painters. Three of them are drawn, as well as engraved, by Mr. Linton, namely, Death’s Door, after Blake (afterwards printed as the frontispiece to Jackson and Chatto’s History of Wood-Engraving), Nature, after Lawrence, and Niobe, after Richard Wilson. Young wood-engravers would do well to examine this collection, and learn what can be effected by the use of the simple line as instanced in the picture of the Three Witches, where Mr. Linton has employed what I shall term the horizontal method with extraordinary success. To Goldsmith’s Traveller and Byron’s Childe Harold, issued by the Art Union, he also contributed some choice engravings.

England lost one of her most distinguished representatives of the graphic arts when, in 1867, Mr. Linton left her shores to make a permanent home in America. He selected, as a residence, a homestead that was once a farm-house, situated in the township of Hamden, just outside New Haven (Conn.), on the old road to Boston; and it is worthy of record that New Haven has afforded shelter for three regicides, and “what more appropriate residence” (says Mr. A. H. Bullen, in the Library) “could be found for so sturdy a republican as Mr. Linton?” Here, at “Appledore” (as he christened his new home), he carried on his engraving work with his usual energetic spirit. For several years he took or sent his blocks to New York (a distance of seventy-four miles) to have them printed, but to avoid the trouble and necessity of doing this, he bought a press, which he subsequently used to great advantage.

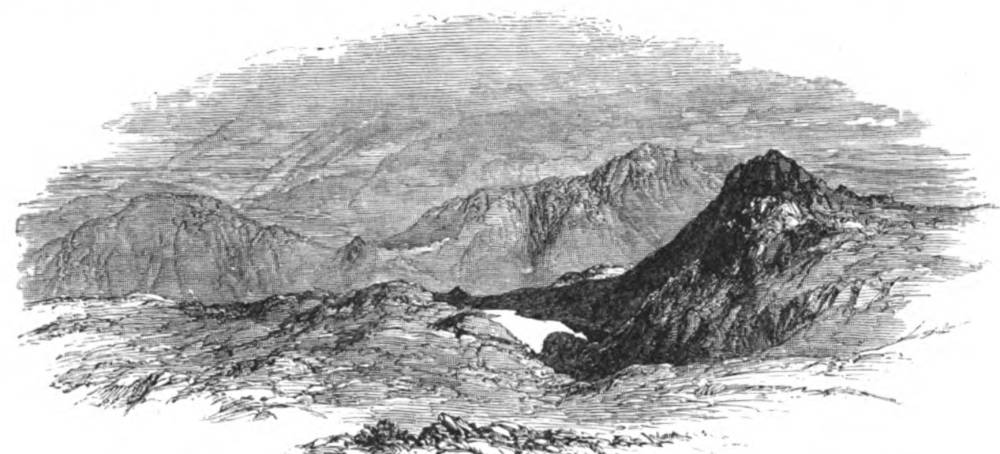

The Pikes from Lea Tarn, drawn and engraved by by W. J.Lindon. (From The Lake Country by permissin of Messrs. Smith, Elder,and Co.

Soon after Mr. Linton’s arrival in America he became connected with the Cooper Institute in New York, where he conducted an engraving school, or class. It was fortunate for the young wood-engravers of America that such an adept should have made his home in their midst. They had for years considered him as a beacon-star in the school of the great English engravers, and his name had an especial cult which embraced nearly all the engravers in America. His Infant Hercules, after Reynolds, his Virgin and Child, after Raphael, and The Haunted House (all published in the Illustrated London News), hung in every engraving office in the land. “Linton,” says Mr. J. P. Davis, a prominent member of the “new school” of wood-engravers,

was the centre and soul of whatever was progressive in wood-engraving then. He meant Art to us, and the lines he cut were, in lieu of nature, our wonder and our study. Each newly-landed English engraver was pestered with questions concerning the tools he used and his manner of working. According as rumour fixed either, we changed our own implements or methods. But little was ascertained, however, until one of our own artists, who stood very high among the craft, visited England. On his return we were told many things of artists whose names were household words with us, but nothing so delightful and surprising as of Linton, who, he said, had been very courteous to him, and had shown him many helpful things about his drawing. It cannot be realized now what an effect that candid admission, by one of the superior beings himself, had upon an engraver. The idea came naturally then that Linton’s distinctive merit was not a matter of tools, but of art culture. Soon after, the great man himself came and made his home among us. We have seen his Lake Country, the illustrations to Bryant’s Flood of Years, and his paintings at the Academy, of which institute he was made a member, and we know he was an artist. He worked with his graver, using just the same kind of intelligence that he used when working with the brush. His bitterest opponents in the so-called New School of engravers ' most heartily desire, I know, that he were now a young man leading in the present advance of the art he has done so much to establish.” [The Century, 1889]

That Mr. Linton’s hand has not lost its cunning is evinced in an engraving executed by him so recently as 1881. This is a woodcut after Titian, the block being produced specially for Mr. P. G. Hamerton’s volume, The Graphic Arts, and the author of that work considers it is the freëst piece of wood-engraving that he has ever seen. Mr. Linton has here acted upon his own doctrine — that not only should a woodcut by done in white line, but that there should be a certain thoughtful vivacity in the line which ought to express the engraver’s intelligent care.

Stickle Tarn, drawn and engraved by by W. J.Lindon. (From The Lake Country by permiss

Mr. Linton has probably done as much to enhance the importance of his art by means of the pen as by the work of his graver. Being aware how little was known concerning its technicalities, he wrote an article on “Wood-engraving " for the June number (1879) of the Atlantic Monthly, which attracted considerable attention. The theories he advanced and the criticisms he expressed were, however, met by the Reviewers in anything but a cordial spirit; but he was equal to the occasion, for, stung by their discourtesy and ignorance of the subject, he defended himself against their attacks in a little volume entitled Some Practical Hints on Wood-Engraving for the Instruction of Reviewers and the Public (London 1888), where, besides censuring the Reviewers for their mistaken opinions, he has given a great deal of information concerning the practice of the art; and, in a later work on the subject — The History of Wood Engraving in America (London, 1882)— he announced his intention of helping towards forming a school of artist-engravers. In 1882, he published an important work on American wood-engraving, which, with the exception of the last chapter, was written for the American Art Review, and has been the subject of animated discussion in American magazines.

I will now draw particular attention to what may be considered as Mr. Linton’s crowning achievement as historian of wood-engraving, the magnum opus upon which he has spent some of his later years in preparing for the press. I allude to the magnificentwork on The Masters of Wood-Engraving, just issued to subscribers (Issued to Subscribers only, at the Residence of the Author, New Haven, Connecticut, United States; and London: B. F. Stevens, 4 Trafalgar Square, Charing Cross. 1889.) certainly the most luxurious thing of the kind that has yet been produced, and will unquestionably be the one authoritative treatise on the subject of which Mr. Linton is incomparably the greatest living master. More than twenty years ago he began his researches at the Library and Print Room of the British Museum, with the object of writing such a history as that which he has just brought to a happy and successful conclusion. His original design, however, was of a much less ambitious character, intending only a supplement to Jackson and Chatto’s Treatise of Wood-Engraving. For many years he had not sufficient leisure to carry out his intention systematically, but eventually he availed himself of permission granted him by the Museum trustees to take photographs of anything he required for the purpose in hand. In 1884 he returned to America with his notes and photographs, and wrote his book; and when the MS. was ready he began printing, having enough material for three copies! The composition and setting - up of the 229 folio pages was the work of his own hands, a feat rendered more remarkable by the fact that, having only type enough for three pages, he was compelled to work off pages two and three, distribute them, and then set up page four to complete the sheet. For more than two years Mr. Linton was hard at work, writing, printing, and mounting photographs required to illustrate two of the three copies; and it was from one of these copies that - letter for letter, and stop for stop — the book just issued was produced. The method adopted by the author may be considered unnecessary, fastidious, and laborious; but Mr. Linton thinks that it is the only method by which he can ensure the correctness and perfection he desires. [Note: ] In the preface to his book (of which but a limited number of copies have been printed ) Mr. Linton states that the reason for its publication arises from the fact of the absence of any treatment of wood-engraving in a manner satisfactory to an engraver. He writes as an engraver, not as a bibliographer; and has not only closely examined all the cuts needed for the History, but has chosen the very finest impressions for photographic reproduction. In some cases he has succeeded in obtaining electrotypes of the original blocks; but the majority of the illustrations are photographic reproductions closely to the size of the originals, and nearly all of them are printed on India paper. Claiming the right of an expert of fifty years’ practice and study of the art, Mr. Linton has corrected a number of misconceptions regarding wood-engraving, furnished some data for accurate judgments, and given examples of the best work; keeping in view one single purpose — “a fair and sufficient exposition of engraving on wood with honour to the masters of the art.”

Mr. Linton’s poems and his early influence as a politician are not, perhaps, so well known to the general public as his artistic skill, but it may be said that as in Art, so in Poetry and Politics his genius ranks high. When quite a young man he seems to have imbibed a taste for political life, and before long he became a zealous Chartist. “I had been brought up,” he writes, “more piously than the Church of England usually requires, but the liberal tendencies of my brother-in-law Thomas Wade, the poet ( hen editor of Bell’s New Weekly Messenger, a semi-radical London newspaper ), some reading of Voltaire and Shelley, and the stirring words of Lammenais in his famous Scripture anathematized by the Pope — the Paroles d ’un Croyant — had brought me in contact with the religious and social and political problems of the time." Ready for active sympathy with the cause of the people, then finding expression in the cry for political enfranchise ment, he projected, in 1838, a sort of cheap library for the people, called The National, consisting mainly of selected extracts from such prohibited works as were beyond the purchasing - reach or time for study of working - men, but his pecuniary resources were soon exhausted. In 1840 he wrote The Life of Thomas Paine (author of The Age of Reason, etc.), and, in 1879, a Memoir of James Watson, who promoted the fight for a free press in England and agitated for the people’s Charter. Four years later he was concerned with Mazzini in calling the attention of Parliament to the fact that the exile’s letters had been opened in the English post-office, which led to a personal friendship with the great Italian and involved him later in European politics, these making a large demand upon his time. In 1848 he was deputed to carry to the French Provisional government the first congratulatory address of English workmen, and in the following year removed to the north, though still engaged in engrossing political work. At this time he edited a twopenny weekly newspaper, The Cause of the People, published in the Isle of Man; but a more important venture was the founding of a London weekly newspaper called The Leader, advocating republican principles, and among those associated with him in the enterprise were George Henry Lewes and Thornton Hunt, who, however, disappointed him, so that he withdrew from the speculation.

Death’s Door engraved by by W. J.Linton after William Blake. By permissin of the Art-Union of London.

In 1850 he was engaged in writing a series of articles on Republican principles, being an exposition of the views and doctrines of his friend, Joseph Mazzini, in a weekly publication called the Red Republican, edited by another old friend, Mr. George Julian Harney, who is still living. Not more than twelve months after this he commenced at Brantwood a publication of his own, first in the form of weekly tracts and then as a monthly magazine. This was The English Republic (which was carried on for four years,

Linton’s articles and action was that Republican Associations 'for the teaching of Republican principles were established in various parts of the country-- among other places at my native town, Cheltenham. I was also one of the three young men who went to Brantwood in the spring of 1854, to help in the mechanical portion of the publication of the English Republic. Here we printed not only that work, but also a Tyneside magazine called the Northern Tribune; but the scheme in which we were engaged was not financially successful, hence the English Republic ceased, the establishment broken up, and the little community we had constituted had dispersed. Just previous to the Brantwood experiment, Mr. Linton had printed for private circulation a volume of poems entitled The Plaint of Freedom. It bears the date 1852. No name was attached to the book, nor was it known, I think, till long afterwards that he was the author. A copy of the work was sent to Walter Savage Landor, who highly eulogised the verses in a sonnet addressed ' To the Author of The Plaint of Freedom, ' and beginning with the lines

Lauder of Milton! worthy of his laud!

How shall I name thee? ' Art thou yet unnamed?

When the Brantwood establishment was broken up, Mr. Linton joined a gentleman named Morin in the publication of an illustrated weekly newspaper somewhat after the style of the present Graphic, to which was given the name of Pen and Pencil. Mr. Linton did, I believe, a good deal of the engraving work as well as most of the literary work connected with the paper. Want of capital, however, caused the failure of the venture, and so it came to an end after an issue of some six or eight numbers.”

The Old Horser engraved by by W. J.Linton after George Morland. By permissin of the Art-Union of London.

A few years ago Mr. Adams visited Mr. Linton at his American homestead, and found him as active as ever, and still interested in political questions. As early as 1842 we find him editing a journal called The Odd Fellow (afterwards changed to The Fireside Journal), for which he wrote, to use his own words, “political leaders, reviews of books and dramatic criticisms (among them reviews on first appear ance, of Dickens’s Old Curiosity Shop and Gerald Griffin’s Gisippus), poetry, answers to correspondents, real and imaginary, anything and everything. In 1845 he succeeded Douglas Jerrold as editor of The Illuminated Magazine, a journal which derived much aid from Albert Smith, Mark Lemon, and Gilbert A Beckett among the writers, and from Leech, Kenny Meadows, H. G. Hine, and other members of the Punch staff as artists; but notwithstanding this array of talent the magazine had but an ephemeral existence. For several years he regularly contributed articles to The Nation during the editorship of Mr. Duffy, as well as writing for the Westminster Review, Examiner, and Spectator; and The People’s Journal (1846), conducted by John Saunders, contains several of his minor poems and prose articles as well as woodcuts.

I have already remarked that Mr. Linton is a poet of no mean order He has contributed occasional verses, sonnets, etc., to many periodicals, and in 1865 appeared a volume entitled Claribel, and other Poems, prettily illustrated by his own hand. About three years later, with his press and some borrowed type, he amused himself with printing, for private distribution, IVind-Falls, a choice little collection of extracts from imaginary plays. In 1882 came the fourth production of the “Appledore Press”-the beautiful anthology, Golden Apples of Hesperus, with exquisitely engraved frontispiece and ornamental headings and vignettes; in the preface to which Mr. Linton states that the whole of that production-drawing, engraving, composition and printing is the work of his own hands at odd times, with long intervals and many hindrances: needless to say the book is of the most chaste and artistic description.

In the spring of 1887 he printed a collection of a hundred lyrical poems, entitled Love-Lore, of which only a very few impressions were taken. “In these verses,” says Mr. A. H. Bullen, “there is that which continually reminds us of the Elizabethan lyrists. " So recently as last year Mr. Linton issued another volume of verse entitled Poems and Translations, which, with a few exceptions, have appeared before. Flowers, and love, and wine, are the subjects of these later poems, and a well-known writer says that Robert Herrick would have recognized in Mr. Linton a kindred spirit, so fluent and so free is the old theme handled; and considers that this volume contains Mr. Linton’s choicest work, his voice having gained a mellower tone of sweetness, these verses being distinguished by taste and feeling, by ingenious fancy and tuneful utterance. In conclusion I will quote that eminent critic Mr. H. Buxton Forman, who says:- — “The poetic doings of William James Linton show power considerably in advance of average performance; and his practical, aggressive republicanism is among the principal factors in keeping him from that fulness of poetic attainment for which he has the capacity.

In this brief account of the many-sided talent of Mr. Linton I have endeavoured to justify my opening statement that he is, without a doubt, one of the most remark able men of the present century, and worthy of every honour due to a great artist.

Bibliography

Kitton, Fred G. “William James Linton, Engraver, Poet, and Political Writer.” The English Illustrated Magazine. 8 (April 1891): 489-5000-. Hathi Trust version of a copy in the Pennsylvania State University Library. Web. 22 January 2021.

Last modified 22 January 2021