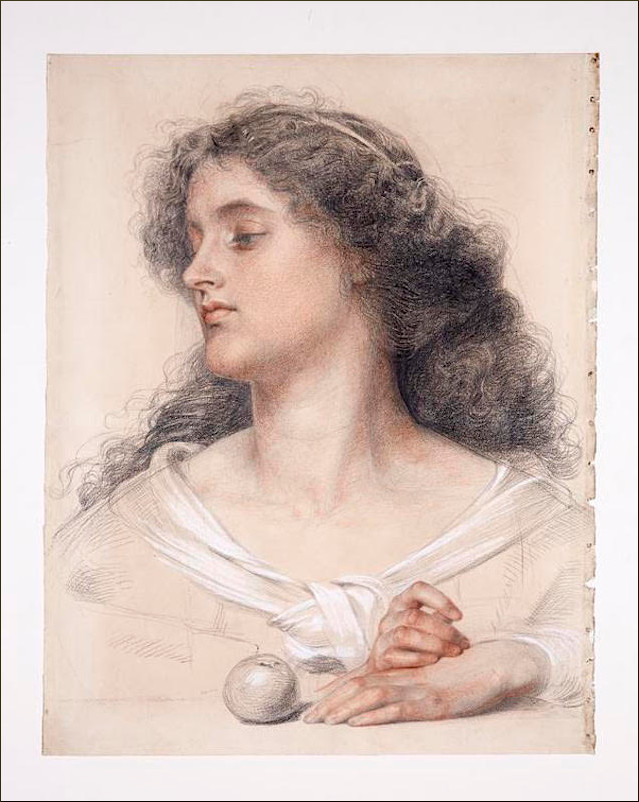

Left: Vivien by Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys (1829-1904). 1863. Oil on canvas. 25 1/16 x 20 11/16 inches (H 64 x W 52.5 cm). Collection: Manchester Art Gallery. Accession no. 1925.70, purchased from E. Mitchell Crosse, 1925. Kindly released by the gallery via Art UK on the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (CC BY-NC-ND.) Right: Vivien. 1863. Black, red and white chalk on buff paper. 23 7/16 x 18 1/8 inches (59.5 x 46 cm). Collection of Norwich Castle Museum, accession no. NWHCM : 1910.14. Image courtesy of Norfolk Museums. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Madeline Hewitson explains that Vivien is an Arthurian character, based on the version of her in the first set of Tennyson's Idylls of the King, published in 1859. "In the poem, the 'wily Vivien' seduces Merlin by 'smiling saucily'" (64). This Vivien looks proud rather than saucy, but the apple in the foreground is enough to confirm that she is a temptress, and the peacock feathers fanned out behind her suggest that she has deliberately set out to allure. Worse, she holds a spray of poisonous Daphne. The colour, clarity, and Pre-Raphaelite precision here are indeed alluring, but she seems to come with a warning. As part of this figure's complexity, Hewitson points out, Sandys departs both from the poem and from nature by using the peacock to suggest female rather than male vanity. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Commentary by Dennis T. Lanigan

Sandys exhibited this painting of the villainous enchantress Vivien, at the Royal Academy in 1863, no. 707. A preliminary drawing for the painting is in the collection of the Norwich Castle Museum. The model for Vivien in Sandys's picture is said to have been Sandys's mistress, the Romany woman Keomi Gray. Betty Elzea, in fact, states: “The model for Vivien was undoubtedly Keomi” (174). As Scott Buckle has pointed out, however, Keomi had black hair and dark brown eyes, whereas the model here has blue eyes and brown hair, and more closely resembles Ellen Smith, who features opposite Keomi in Rossetti’s The Beloved. Vivien is one in a series of Arthurian subjects the artist painted between 1861 to 1864 as well as one of the earliest of Sandys's portrayals of a femme fatale. As Allen Staley has commented, "For Sandys himself, beautiful but vicious ladies would become the staple of his art during the following decade [the 1860s]" (75). These included such works as Cassandra, Judith, Morgan le Fay, and Medea - devious and wicked women, including witches and seductresses, taken from classical myths, Arthurian legends, or the bible.

In Arthurian legends and as retold in Alfred Tennyson's poetic work Idylls of the King, a cycle of twelve narrative poems published between 1859 and 1885, Vivien is portrayed as a sorceress and seductress who is taught magic and the use of spells by the wizard Merlin. Vivien later, through her cunning, turns Merlin's spell against him, entrapping him in a cave and thus ending Merlin's influence in the Arthurian world. In Thomas Malory's Morte d' Arthur the enchantress is referred to as Nimue and not Vivien, as in Tennyson's work. In Sandys's painting, however, there is little to suggest the evil deeds the sorceress was associated with unlike in paintings by Edward Burne-Jones such as his mural of Merlin and Nimue for the Oxford Union Debating Hall in 1857, his early watercolour Merlin and Nimue of 1861 or his major oil painting The Beguiling of Merlin of 1872-77. In the later painting Merlin is portrayed as bewitched and helpless, trapped in a hawthorn bush, as Nimue stands nearby reading from a book of spells.

On Art UK the painting is described in this way: "Head and shoulders of a young woman, in profile facing to the left, her hands resting on an ornate green and white tiled parapet. Her white, fleshy throat forms the centre of the composition. She wears a luxurious gilt embroidered shawl with an interlocking geometric pattern and an edging of tiny pearls, and a string of heavy red beads, possibly carnelian, around her neck, with matching red earrings. Her thick dark wavy hair flows down her back. She holds a sprig of poisonous flowering daphne in her left hand, which she rests on her other hand, which is palm down on the parapet. An apple and a red poppy lie on the ledge in front of her, with some fallen leaves and petals from the sprig in her hand. She is set against a backdrop of radiating peacock feathers."

Allen Staley has pointed out details of the painting which result in its feeling of sumptuousness, including the parapet which

appears to be inlaid with engraved, fretted, and stained ivory panels, not unlike a kind of Indian craftwork, and which continues over the horizontal shelf and its leading edge onto two odd and seemingly inexplicable small geometrical structures rising above the shelf on either side of the picture. Vivien's garment consists mainly of patterns of a bold geometrical Interlace in gold, outlined in red on a black ground, and the upper background is iridescent with shimmering colors of peacock feathers. All this adds up to a sumptuously rich tout ensemble. The figure is painted with assurance; her hair is delineated with a precision that registers every stray wisp, and the reddish shadows under her pellucid (agate?) earring and necklace, as well as the varied markings of the different beads of the necklace, are lovingly observed. The artist's virtuosity is evident. [78]

This is a quintessential example of l'art pour l'art [art for art's sake] of this period, where Sandys is indifferent to what the title of the work tells us the subject is and makes no attempt to elucidate the Arthurian story, but is instead purely concerned with beauty.

Many of the accessories used in this painting may have been used for symbolic purposes, to warn of Vivien's evil nature, although Staley felt they were more intended as "beautifully painted details than as bearers of messages" (78). The apple could perhaps symbolize her role as temptress relating to the Fall of Man while the poisonous daphne plant and the opium poppy of obliteration relate to her role as enchantress. The red rose may be symbolic of passion, related to Merlin's obsession with his protégé. Betty Elzea notes that while peacock flowers have a dazzling beauty they are reputed to bring ill luck (174). Sandys was not the only artist within the extended Pre-Raphaelite circle to incorporate peacock feathers as a decorative accessory in paintings. Examples included Frederic Leighton's Pavonia of 1859, G.F. Watts's A Study with Peacock Feathers and F.G. Stephens's Portrait of Clara Stephens of c.1865. Sandys would have seen Leighton's painting displayed at the International Exhibition held at South Kensington in 1862. Sandys's painting also has much in common with Rossetti's ground-breaking painting Bocca Baciata of 1859. Julian Treuherz has characterized Vivien as another in a series of Pre-Raphaelite works produced in the 1860s inspired by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Venetian Renaissance art: "This fanciful portrait of a luxuriously attired female conveys a heady atmosphere of sensuality and mystery, with none of the directness of the early Pre-Raphaelite vision. This type of half-length female portrait, cut by a parapet, is based on Venetian models, but was adopted by Rossetti in the late 1850s and 1860s, and taken up by his followers. Joli Coeur of 1867 is a typical example of Rossetti's own work in this vein. Both figures have the air of a femme fatale, with the full lips, broad neck and flowing hair admired by Rossetti. Vivien, painted in the bright and sharp style of early Pre-Raphaelitism, shows the enchantress of Arthurian legend" (101).

Contemporary Reviews of the Painting

When the painting was shown at the Royal Academy in 1863 the critic for the Art Journal preferred his superb portrait of Mrs. Susannah Rose: "In the fancy-feigned head of Vivien (707), also by Mr. Sandys, the elaboration of detail has been directed to the consummation of a sumptuous colour" (110). F. G. Stephens in the Athenaeum praised its brilliancy: "Near it is a highly-poetical head of Vivien (707), by Mr. F. Sandys, put so that its irrepressible brilliancy alone can be seen" (655). Slightly later Stephens expands on his review: "Our progress brings us now to Mr. F. Sandys's splendid head, life-size, of Vivien (707), the alluring witcher of Merlin, entrancing in haughty beauty and crowned with gold-lighted hair; behind her a screen of eyes from a peacock's tail, her apt cognizance" (657). C. L. Eastlake in London Society admired both Sandys's draughtsmanship and colour: "La Belle Ysoude (606) and Vivien (707) are two noble studies by Mr. Sandys, exquisitely drawn and glowing with lovely colour" (505).

Bibliography

Banham, Joanna and Jennifer Harris. William Morris and the Middle Ages. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984, cat. 115, 169-70.

Eastlake, Charles Locke. "The Royal Academy Exhibition." London Society III (June 1863): 539-50.

Elzea, Betty. Frederick Sandys 1829-1904. A Catalogue Raisonné. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Antique Collectors' Club Ltd., 2001, cat. 2.A.60, 174.

Hewitson, Madeline. "Unweaving the Rainbow: Nature's Colours in Art, Fashion and Design." Colour Revolution: Victorian Art, Fashion & Design. Edited by Charlotte Ribeyrol, Matthew Winterbottom and Madeline Hewitson. Oxford: Ashmolean, 2023. 59-69.

Hoberg, Thomas. "Duessa or Lilith: The Two Faces of Tennyson's Vivien." Victorian Poetry XXV (Spring, 1987): 17-25.

Skinner, Sarah. "Sandys, Frederick: Vivien. Manchester Art Gallery. Web. 14 July 2025.

"The Royal Academy." The Art Journal New Series II (1 June 1863): 105-16).

Staley, Allen. The New Painting of the 1860s. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011, Chapter Three, "Frederick Sandys," 77-79.

Stephens, Frederic George. "Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1855 (May 16, 1863): 655-57.

Treuherz, Julian. Pre-Raphaelite Paintings from the Manchester City Art Gallery. London: Lund Humphries, 1980, 100-01.

Vivien. Art UK. Web. 18 October 2023.

Vivien. Norfolk Museums Collections. Web. 14 July 2025.

Created 27 July 2020

Last modified (drawing and commentry added) 14 July 2025