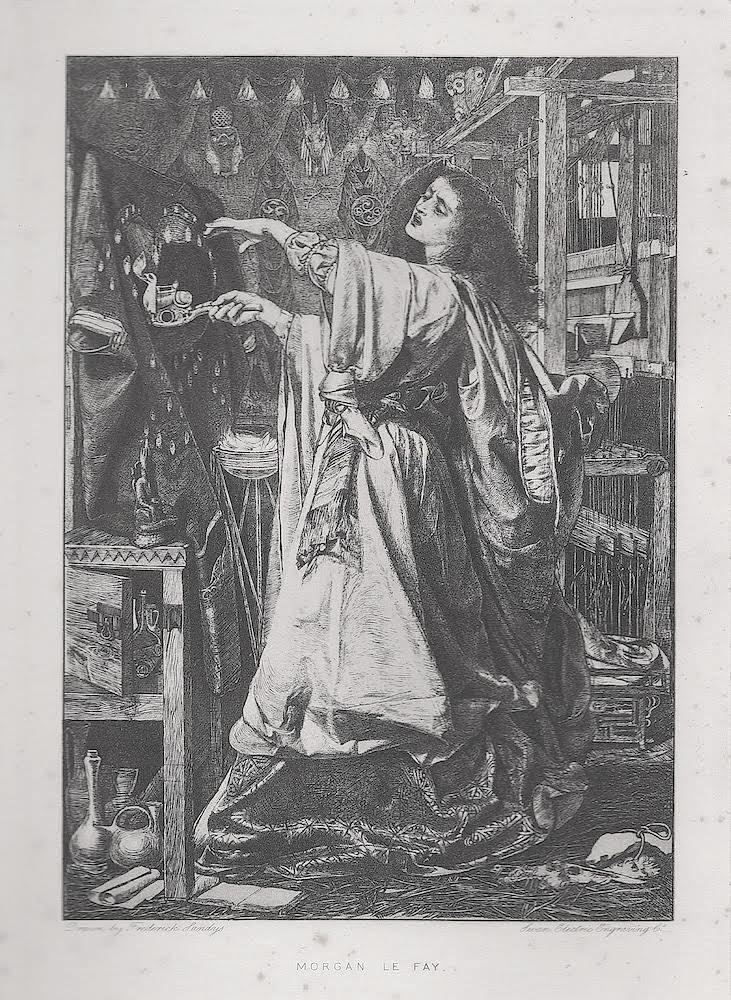

Left: Morgan le Fay by Frederick Sandys. 1863-64. Oil on panel. 24 ¾ x 17 ½ inches (61.8 x 43.7 cm). Collection of Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, accession no. 1925P104. Image courtesy of Birmingham Museums Trust made available via Art UK under a Creative Commons Zero licence (CCO). Right: another version of Morgan le Fay by Sandys, in brush and brownish-black ink on paper. 24 3/8 x 17 3/16 inches (59.3 x 43.6 cm). Private collection. Image courtesy of Sotheby's.

Sandys exhibited Morgan le Fay [Morgan the Fairy], surely one of his greatest masterpieces, at the Royal Academy in 1864, no. 519. The composition is based on a highly finished preliminary drawing in brush and brownish-black ink of c. 1863, that is now in a private collection. The composition of the oil follows the drawing closely and both versions show Morgan chanting spells in front of the garment, intended to consume anyone who puts it on with fire, that she has woven to present to her half-brother King Arthur. Betty Elzea has described the composition of the drawing in comparison to the painting as follows:

Full-length figure of a young woman in voluminous robes, facing to the left. Her head is turned upward and faces slightly towards the spectator. She faces a low cupboard, to the left. Above this is suspended a richly-decorated robe to which she is attaching magic flames with an exotic (Far-Eastern?) pipe-like device in her right hand. Little tongues of fire sprout from all over the robe. She raises her left hand and chants, as though casting a spell. Between her and the robe is a burning tripod brazier containing a crucible. In the background is a frieze in ancient Egyptian style of a row of animal-headed gods, with interposed Celtic or Japanese decorative roundels. To the right, behind the figure, is a loom on which two owls perch. The floor is strewn with rushes. Placed about the floor and inside the half-open cupboard are pottery and glass vessels, which are antique or exotic in form, books, scrolls, a loom-weight, and a shuttle. A small statue of the Hindu god Ganesha rests on the corner of the cupboard. The figure's underskirt has an intricate pattern, which is identical to the one on the robe worn by Vivien…. However, Sandys made some changes of detail in the picture: the textile sash in the drawing has been changed to a leopard skin in the painting; the patterned underskirt in the drawing has been altered to a plain one in the painting; the plain overskirt in the drawing has had a border of motifs copied and adapted from Pictish symbols added to it in the painting; the enchanted robe in the painting has more decorations (embroidered interlace designs, also Pictish-inspired) on it than in the drawing (but there are less tongues of flame depicted); the plain low cupboard of the drawing has become elaborately carved and painted in the painting, and the books and scrolls on the floor in the foreground have had illuminations added to them in the painting. [176-77]

The model for Morgan le Fay was once again Sandys's mistress, the Romany woman Keomi Gray. Scarlett Moberly feels Sandys used "this mish-mash of Oriental iconography to enhance a sense of mystery and danger"(15).

Morgan le Fay was reputedly the half-sister of King Arthur Pendragon but the nature of their relationship varies with the various Arthurian legends as Sally-Ann Huxtable has explained:

The figure of Morgan le Fay is an erratic element in medieval and post-medieval Arthurian literature. She first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's c.1150 Vita Merlini as one of nine sister enchantresses with healing powers who dwell on the Isle of Avalon. It is to Morgan and her sisters that the gravely wounded King Arthur is taken to be healed. However, by 1485 when William Caxton published Thomas Mallory's Le Mort d' Arthur, Morgan le Fay has become Arthur's half-sister and his mortal enemy; a highly gifted astrologer and practitioner of nigromancy [black magic], and an avowed enemy of the virtues of chivalry embodied by Arthur, Guenevere and the Knights of Round Table. In Sandys's painting this wild and vivid sorceress is casting the spell to make deadly the mantle with which she hopes to kill Arthur. What is most captivating in this painting is that Sandys's Morgan feels as much human as she is supernatural. Her expression is part rage and part anguish; and yet she is a magician in the act of destructive creation. It is this tension between her earthly humanity and her occult powers that are at the core of the work; she is a woman possessed by forces beyond even her control, and when she unleashes them all does not go to plan. [68]

Huxtable goes on to discuss why Morgan felt compelled to wreak havoc on Arthur: "Is this jealousy fuelled by the fact that her gender precludes her from the power and glory that her brother is able to achieve as a man and a king? Her gifts seem as powerful as his yet she has no positive outlook for them and therefore she has embraced darkness. Ultimately though this story is driven by unseen forces - the occult powers of 'darkness' that Morgan has learned and which drive and make manifest the hatred she feels for her brother; this is the stuff of fate, of unstoppable forces and archetypal passions and relationships" (72).

Joanna Banham and Jennifer Harris point out the various ways in which the nature of Morgan's chamber emphasizes her "complete immersion" in black magic: "Morgan's bewitching beauty complements the sumptuousness of her costume, but is marred by the extremity of her feelings and actions. Her face is drawn and somewhat haggard, her expression almost anguished, whilst her body seems to recoil from the completion of her task. The sorceress's chamber is cramped and claustrophobic. Alchemical vessels and potions litter the floor and are visible in cupboards, while eccentric ornament decorates the walls and furniture. These suggest both the fanatical nature of Morgan le Fay's knowledge and her complete immersion in the art of magic" (169).

Jan Marsh has interpreted the painting in this way: “The violence of her desire is expressed in the harsh, abrupt lines of her gesture, and in the sinister patterning behind. Alchemical vessels and books litter the floor, occult symbols decorate her gown, and a sense of primitive animality is conveyed by the fire, the exotic carved figure and the leopard-skin apron. However, the plethora of stage props also tends to undermine the intended atmosphere of evil. Morgan’s room is cramped and claustrophobic and an owl, her familiar spirit, perches atop the loom” (118).

Huxtable has pointed out the symbolic references to some of the objects portrayed in the painting:

On the low cabinet upon which she is conducting her work is a wild green and gold figure - it seems to be the figure of the Green Knight fought by Sir Gawain, or a Green Man. As a pupil at the Norwich School, Sandys would have been only too aware of the green and gold foliate head (now known as Green Men) bosses in the cloister of Norwich Cathedral next to his school, and his interest in antiquarianism would mean he was aware of numerous foliate heads and depictions of Woodwose (the Wild Man of the Woods), in the churches of Norfolk & Suffolk. Morgan herself wears the fairy colour green, signalling her connections to wild and untamed nature and magical forces, as does the leopard skin worn round her waist, which also hints at the non-European magical traditions she has learned. On the cabinet sits a figure of the Hindu deity Ganesha who is regarded as a remover of obstacles and the Deva of learning and wisdom. Two owls sit on the rafters denoting occult wisdom, death, and the underworld and the dangerous forces of the night. Behind her, strange animal gods that look almost-but-not-quite Egyptian glower from the wall. In her hand is a brazier that looks to be in the form of a mythical beast of Middle Eastern origin. [70]

Allen Staley feels that "Such details, freely adapted from a variety of sources no way Arthurian or even medieval, combine together to create an atmosphere both sinister and exotic" (80).

Contemporary Reviews of the Painting and Drawing

Morgan le Fay, engraved by Swan Electric Engraving Co. after the drawing by Frederick Sandys. Frontispiece to Gleeson White’s English Illustration: The Sixties 6 1/2 x 4 5/8 inches (16.7 x 11.8 cm) – image size. Private collection, image courtesy of the author.

When Sandys exhibited the painting at the Royal Academy in 1864 it was, in general, not particularly favourably reviewed. The critic of the Art Journal did not class himself amongst its admirers: "F. Sandys, whose portraits in this and last exhibition have roused little short of a sensation, seeks to provoke no less admiration – not to say astonishment and dismay – in an altogether anomalous production, Morgan-le-Fay (519). The figure is mediaeval, a petrified spasm, sensational as a ghost from a grave, and severe as a block cut from stone or wood. We are happy to hear that the work is not without admirers, fit, though possibly few" (161).

F.G. Stephens writing in The Athenaeum found this work powerful but felt a public not well versed in the Arthurian legends needed a better explanation as to the tale depicted: "His Morgan-le-Fay (519) ought not to have been presented without explanation to a public hardly enough versed in the Arthurian cycle of legends to recognize its theme at sight. It represents the enchantress in her 'chamber of imagery,' and performing a magic ceremony before a garment; it is treated with strange force of expression and poetic suggestiveness. All the accessories have been studied with care; the painting is powerful" (682). A reviewer for The Illustrated London News obviously wasn't familiar with the Arthurian legends even getting the title of the picture incorrect: "However, Mr. Sandys has a subject picture which is more free in execution, though scarcely intelligible in arrangement. It represents 'Morgran-le-Fay' [sic] (519) – the wicked Fairy Queen, sister of King Arthur – in her chamber, with a blazing tripod, crucibles, and lamp with mystic flame, throwing some enchantment over a garment destined for one of her victims" (519).

In 1879 the periodical The British Architect (Manchester) reproduced the drawing of Morgan-le-Fay by photo-lithography on page 169 and described the work: "Mr. Frederick A. Sandys, pen and ink drawing, a photo-lithograph of which we republish this week, illustrates the royal witch at her unholy work upon the jewelled mantle. The mystic garment has been fashioned by her own hands in the loom which fills the extreme right of the drawing; the jewels have been fastened on, and, as she passes over it the enchantment of her unearthly fire, she chants her direful incantation" (172-73).

Edward Burne-Jones did a large watercolour of Morgan le Fay in 1862, now part of the Cecil French bequest to the Hammersmith & Fulham Council. There is no similarity between the two works, however, so it is unlikely that it was a source of direct inspiration for Sandys's drawing and painting of the following year.

Links to Related Material

- The Arthurian Revival as an Answer to a Changing World

- The Legend of King Arthur: A Pre-Raphaelite Love Story

- Circe and Other Sorceresses

- Sir George Frampton's Morgan le Fay door panel

Bibliography

Banham, Joanna and Jennifer Harris. William Morris and the Middle Ages. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984, cat. 115, 169-70.

Elzea, Betty. Frederick Sandys 1829-1904. A Catalogue Raisonné. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Antique Collectors' Club Ltd., 2001, cat. 2A.66, 176 and cat, 2.A.67, 177-78.

"Fine Arts. Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Illustrated London News XLIV (May 26, 1864): 518-19.

Huxtable, Sally-Anne: '"Her False Crafts": Morgan Le Fay and the Wild Women of Sandys's Imagination." PRS Review XXIV (Autumn 2016): 66-77.

Important British Paintings and Drawings from 1840 to 1960. London: Sotheby's (10 November 1981): cat. 30.

Marsh, Jan. Pre-Raphaelite Women: Images of Femininity. New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987. 118.

Moberly, S. Scarlett. "The magic of Orientalism Myth and witchcraft in Morgan le Fay by Frederick Sandys." The British Art Journal XXI (Spring 2020): 15-19.

Morgan Le Fay. Art UK. Web. 15 July 2025.

"Morgan le Fay." The British Architect (1879): 169-74.

Osborne, Victoria. Victorian Radicals. From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts & Crafts Movement. Martin Ellis, Victoria Osborne, and Tim Barringer. New York: American Federation of Arts, 2018, cat. 62, 181.

Newall, Christopher. The Age of Rossetti, Burne-Jones & Watts. Symbolism in Britain 1860-1910. Andrew Wilton and Robert Upstone Eds. London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1997, cat. 34, 139.

"The Royal Academy." The Art Journal New Series III (June 1, 1864): 157-68.

Staley, Allen. The New Painting of the 1860s. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011, Chapter Three, "Frederick Sandys." 71-88, pp. 78-80.

Stephens, Frederic George. "Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1907 (14 May 1864): 683-84.

Van Os, Henk W. Femme fatales, 1860-1910. Groningen: Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten, 2003. 146-47.

Wildman, Stephen. Visions of Love and Life. Pre-Raphaelite Art from the Birmingham Collection, England. Alexandria, Virginia: Art Services International, 1995, cat. 77, 240-41.

Created 15 July 2025