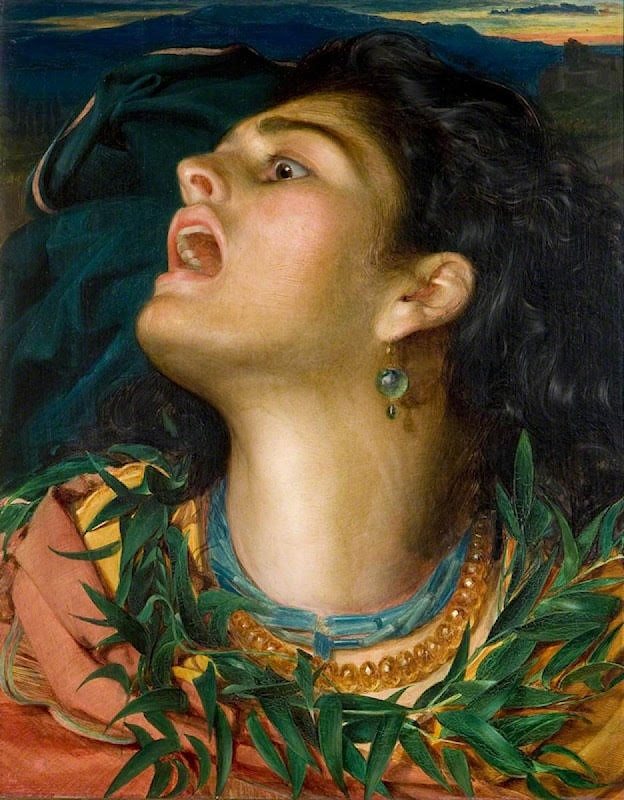

Left: Cassandra by Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys. c.1863-64. Oil on millboard panel. 11 7/8 x 10 inches (30.2 x 25.4 cm). Collection of Ulster Museum, Belfast. Image courtesy of the Ulster Museum NI, reproduced for purposes of non-commercial academic research. Right: Cassandra. 1895. Coloured chalks on greenish-blue paper. 14 1/8 x 21 inches (35.8 x 53.3 cm). Private collection. Image courtesy of Christie's (right click disabled; not to be downloaded; but a somewhat larger version of it can be seen here).

Sandys exhibited Cassandra at the Royal Academy in 1865, no. 503, and then later at the Leeds Fine Art Exhibition in 1868, no. 1452. The story of Cassandra comes from the story of the Trojan War in Homer's The Odyssey. She was a princess of Troy and a priestess, the daughter of King Priam and Queen Hecuba. She was renowned for her ravishing beauty. Apollo fell in love with her and promised to grant her anything she asked for if she loved him in return. She asked for the gift of prophecy. However, when she broke her promise and spurned his advances, he twisted her gift so that, although she was able to predict the future with absolute accuracy, no one would ever believe her. She foresaw that her brother Paris's journey to Sparta and his subsequent abduction of Helen, the wife of King Menelaus, would result in a war that would ultimately lead to the destruction of Troy but her warnings were ignored. Her most famous prophecy was predicting the catastrophe of the Trojan horse but again her pleadings to destroy the wooden horse were dismissed as the ravings of a madwoman. Although she survived the fall of Troy she was captured by King Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek forces, and taken back to his homeland Mycenae as his concubine. Upon reaching Mycenae, Cassandra and Agamemnon were murdered by Clytemnestra, Agamemnon's wife, as revenge for sacrificing her daughter Iphigenia just before the start of the Trojan War. Once again Cassandra had predicted their murders but her warnings had been ignored by Agamemnon. Sandys's source of inspiration for this painting may not have come from Homer, however, but from his friend George Meredith's poem, "Cassandra." It captures well the lines from verse III of the poem:

Once to many a pealing shriek,

Lo, from Ilion's topmost tower,

Ilion's fierce prophetic flower

Cried the coming of the Greek!

Black in Hades sits the hour.

Betty Elzea has described the painting in this way: "Head and shoulders of a young dark-haired woman. Her head is raised and turned to the left. Her eyes are staring to the left, and her mouth is wide open as if she is shouting or screaming. Around her neck are two necklaces and a wreath of leaves. She wears a ball-shaped earring with a pendant tear-shaped drop. Behind her the wind billows out her cloak, and in the background is a distant coastal landscape, seen as from a height" (175). Cassandra certainly appears to be screaming out one of her prophecies of warning with almost a look of madness in her eyes. The wreath around her neck appears to be of myrtle leaves, but it is not known whether Sandys intended these for decorative or symbolic purposes. In ancient Greece, myrtle was sacred to the goddess Aphrodite and associated with love, beauty, and pleasure. The ancient Greeks also believed a myrtle garland signified the same as an olive branch - peace, victory and prosperity. The latter meaning might make it an appropriate symbol for a princess involved in the Trojan war. But laurel leaves might have been a more appropriate choice since the laurel was considered sacred to Apollo who adorned himself with laurel leaves. The leaves in Cassandra's wreath, however, look too thin to be laurel. The model for Cassandra is again the Romany woman, Keomi Gray.

Contemporary Reviews of the Painting

The critic for the Art Journal made most of his remarks about Sandys's Gentle Spring merely mentioning that "Mr. Sandys has another picture, Cassandra (503), a head of chiseled features, passionate in tortured agony" (166). A reviewer for The Illustrated London News disliked the painting's subject finding it disagreeable: "The same painter's Cassandra (503) raving her unheeded prophecies is an extravagantly unpleasant subject for a single head" (451). The most extensive review of the painting was by F. G. Stephens in The Athenaeum who felt it lay within the range of Sandys's artistic abilities: "A subject that is entirely within the range of Mr. Sandys's ability, because it is dramatic rather than imaginative in character, was supplied to him by the legend of Priam's Daughter, No. 503, which, bearing the name of Cassandra, represents her with great spirit and in a most original manner; with sideway placed head and open mouth the prophetess shouts out her threats and warnings. The expression of the furiously inspired princess is given here with extraordinary force and felicity of conception; she is tawny, even ruddy of colour, black haired, with gleaming eyes; the unrestrained passion of her action tosses the Phrygian mantle about her" (657).

Other Versions of Cassandra by Sandys

Sandys later did a drawing for a wood engraving by Joseph Swain entitled Helen and Cassandra published in Once a Week on 28 April 1866, opposite p. 454. Sandys also did a chalk drawing of the subject in 1895. Betty Elzea has described this as: "A bust of a wild-looking young woman facing half to left. Her eyes are staring and her mouth is open. Her red hair and white head scarf are blowing in the wind towards the left. She wears white and reddish draperies. Behind her, in monochrome, are the castle and walls of Troy" (283). Certainly if the earlier oil version suggested mental instability in Cassandra, she looks positively deranged in the chalk version. The model for Cassandra in the chalk drawing appears to have been one of Sandys's daughters. An image of the chalk drawing was reproduced in The Studio in October 1904, p. 13. When this drawing came up for auction at Christie's in 2022 their experts had these comments: "The strength of Sandys' image is enhanced by its compositional format; we are confined by its peripheries, blind to the wider surround, as the Trojans were oblivious to Cassandra's prophecies. Cassandra's hair and garments billow out behind her, as if she [was] animated by a seemingly centrifugal force of heightened consciousness, in contrast to the still equanimity of the city beyond." Sandys was obviously pleased with the drawing, as shown by his comments in a letter of 1 March 1895 to his friend W. Graham Robertson: "I do not hesitate to say it is the best thing I have ever done" (qtd. in Elzea, 283).

In Victorian art perhaps the other well-known painting of Cassandra is Evelyn de Morgan's Cassandra of 1898 where she is portrayed standing alone with her hands gripping her hair outwards in anguish as Troy burns in the background. D.G. Rossetti did a pen-and-ink drawing of Cassandra in 1861 that is now in the collection of the British Museum. Edward Burne-Jones executed a red chalk drawing of The Head of Cassandra of c.1866-70 where the model appropriately was his mistress Maria Zambaco. It is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Bibliography

Bate, Percy "The Late Frederick Sandys: A Retrospective." The Studio 33 (October 1904): 3-17.

British and European Art. Part I. London: Christie's (December 13, 2022): lot 28.

Dijkstra, Bram. Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986. 48.

Elzea, Betty. Frederick Sandys 1829-1904. A Catalogue Raisonné. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Antique Collectors' Club Ltd., 2001, cat. 2A.63, 174-75 and cat. 5.22, 283.

"Fine Arts. Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Illustrated London News XLVI (13 May 1865): 451.

Lawless, Julia. "Myrtle: Symbol of Love & Beauty." Aqua Oleum. Web. 15 July 2025 https://aqua-oleum.co.uk/2022/02/14/myrtle-symbol-of-love-and-beauty/

"The Royal Academy." The Art Journal New Series IV (1 June 1865): 161-72.

Stephens, Frederic George. "Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1959 (13 May 1865): 657-58.

Created 15 July 2025