The exhibition is being held at Leighton House Museum in Kensington from 24 May-21 September 2025. Many thanks to both the museum and Scott Buckle for allowing us to reproduce the images included here. Click on all the images of individual works to enlarge them, and for more information about them. — Jacqueline Banerjee.

he Victorian Treasures exhibition fully lives up to its name. It is a visual treat featuring twenty-one paintings and drawings from the Cecil French Bequest to the Fulham Public Libraries, now the property of the London Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham, and twenty-one drawings and watercolours from the Scott Thomas Buckle collection.

An installation shot. Edward Burne-Jones wall, © Cecil French Bequest, London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. Image credit, Jaron James.

This is not the first time I have had the opportunity to view works from both these collections and certainly this is not the first time that the Cecil French collection has been shown at Leighton House. What ties this exhibition together is that, despite collecting some seventy years apart, both collectors were long term residents of Fulham and both were particularly keenly interested in the Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Movements. Cecil French was born in Dublin in 1879 and trained to be an artist, initially at the Royal Academy Schools and then at Sir Hubert von Herkomer's school at Bushey. By early in the twentieth century, however, he had largely abandoned his artistic career. He appears to have had private means. He settled in Fulham and amassed the important collection for which he is now best known. Scott Buckle is a well-known scholar and art collector with a particular interest in nineteenth-century British drawings and Victorian artists' models. He began collecting in his twenties in the 1980s and has subsequently assembled a large and eclectic collection of British drawings, watercolours and paintings. Scott's reasons for collecting drawings very much mirror my own because drawings allow you to see the artist's mind at work. As Scott says: "Drawings give you an insight into an artist's process - you can see them figuring out something in the moment, thinking through a particular detail or how the composition will fit together. They allow you to get closer to the artist at work." Scott first became aware of the Cecil French collection when it had earlier been exhibited at Leighton House in 1986 and this experience became a significant factor in inspiring the subsequent direction his own collection would take.

At his death in 1953 French had stipulated in his will that nothing was to go to the (then) Tate Gallery because he loathed the modern art that was the current focus of the Tate's collection policy. French's collection of 153 paintings and drawings was therefore widely dispersed to a number of other British public galleries. The London Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham received 52 works in total. In addition to Victorian paintings French also collected works by his own contemporaries, such as Frederick Cayley Robinson, William Shackleton, and Charles Haslewood Shannon, all of whom are represented in this exhibition. This bequest contains many remarkable Victorian works. Despite this John Christian, who knew the Cecil French collection well, makes an interesting point about French as a collector, particularly considering he was collecting at a time when this type of art had fallen almost completely out of fashion: "Nonetheless a suspicion persists either that French's eye was not always as good as it might have been, or that, like many collectors, he was too much of a bargain-hunter, unprepared to stretch himself and buy the best that he could (or indeed, strictly speaking) could not afford" (12). In truth this criticism about being a bargain hunter can well be levelled against many collectors, myself and Scott included. One example in French's collection that brings Christian's point home is G.F. Watts's painting of Diana and Endymion. Although interesting from a scholarly standpoint this painting pales as compared to the similarly titled work of an entirely different composition that Watts completed in 1873 and exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1881. I had the good fortune to see this painting in Australia when it was in the John Schaeffer collection and then later at the Maas Gallery. This is one of the most beautiful works Watts ever painted and surely works of this quality by Watts would have been available for reasonable prices when French was collecting.

Two of the paintings on display. Left: Burne-Jones's watercolour of 1875, The Wheel of Fortune; right: Albert Moore's oil painting of 1866, Apricots. Both © Cecil French Bequest, London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. Image credit, Jaron James.

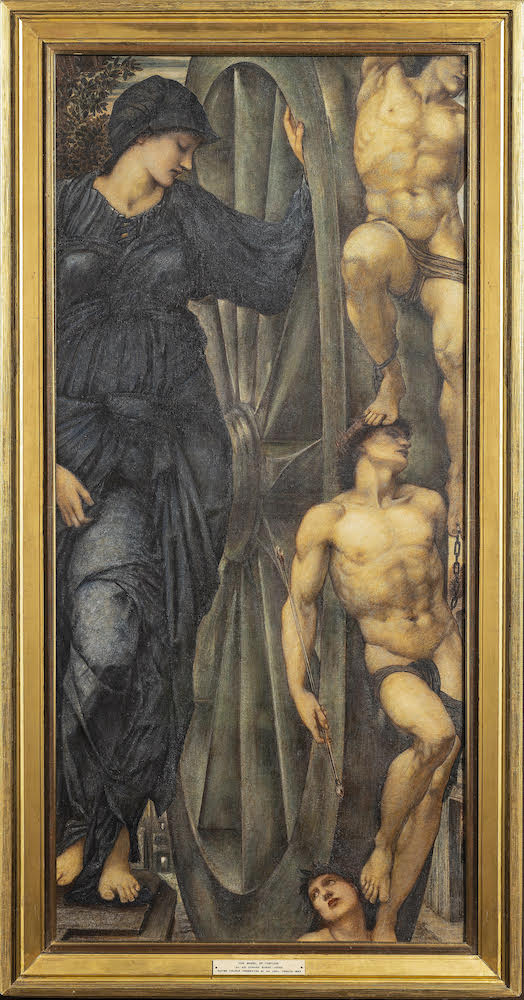

Despite this criticism, there are still many outstanding Victorian pictures and drawings in French's collection. His bequest to Hammersmith & Fulham, for instance, included 25 works by Edward Burne-Jones, surely his favourite artist, and about whom he wrote in 1947: "Edward Burne-Jones's drawings are beyond everything." Of the Burne-Jones works on display at Leighton House I would particularly single out his gouache painting of The Wheel of Fortune, probably the second-best of the seven known versions of this picture, only surpassed in quality by the oil version at the Musée d'Orsay. Burne-Jones's Cupid delivering Psyche is a gorgeous example of his work from the 1860s and another highlight. Another favourite painting of mine in the collection was Albert Moore's Apricots, an early work from 1866, one of his first works to be signed with his anthemion device, and also one of his first works to feature the combined influences of Classicism and Japanese art. It was painted in the same year as another of my favourite works by Moore, Pomegranates, that I also saw at the Guildhall Art Gallery during my visit to London. Both are absolutely stunning works and it was surprising to me to learn they had both belonged to Cecil French.

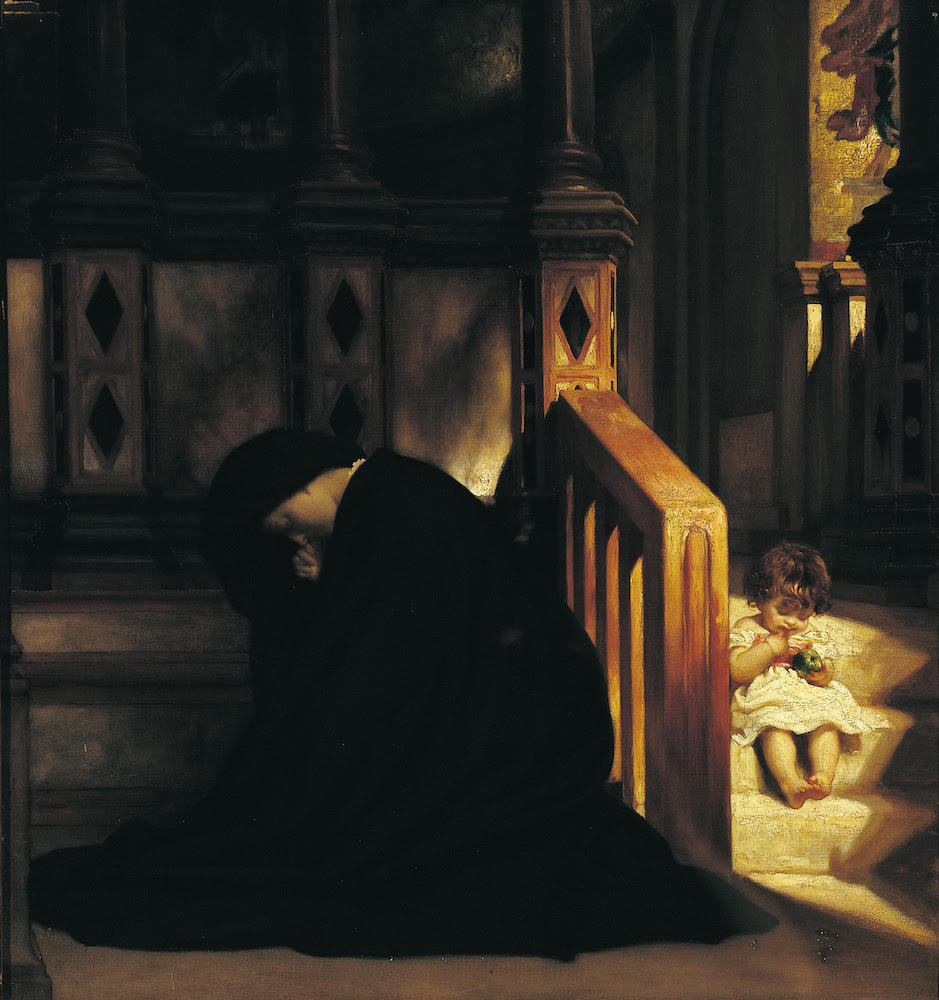

Also on display here, Lawrence Alma-Tadema's The Pomona Festival of 1879 is a fine and characteristic example of the mature work for which he is now best known, while Frederic Leighton's The Widow's Prayer of c.1864-65 is an early work showing the influence of Venetian High Renaissance art. The latter is a truly beautiful painting, particularly in the artist's handling of light and shade, but it is not well known as compared to his later masterpieces of the Aesthetic Movement. J.W. Waterhouse's Mariana in the South is a charming picture, and certainly a solid example of the artist's work, but again not in the first rank of his masterpieces. Still, these particular paintings to me were the highlights of the show.

Left: Frederic Lord Leighton's oil painting of The Widow's Prayer of 1864-65. Right: Lawrence Alma-Tadema's oil painting of The Pomona Festival of 1879. Both © Cecil French Bequest, London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. Images credit, Jaron James.

The entire Cecil French Collection was also expertly displayed against a pale blue background and well lit so the works showed up much better than when I had seen the collection on previous occasions at Leighton House when it was dispersed through the main floor of the house, particularly the drawing room.

An installation shot showing the the selection of works from Scott Buckle's collection in the Tavolozza Drawings Gallery. Courtesy of the Scott Thomas Buckle collection. Image credit, Jaron James.

The selection from Scott Buckle's collection of works on paper was exhibited in the Tavolozza Drawings Gallery, constructed during the recent renovations carried out at Leighton House. When I had my own drawing exhibition at Leighton House in 2016, Pre-Raphaelites on Paper, my show was displayed over the entire house and I was allowed to select and show 100 drawings, which gave a good indication of the scope of my collection. Scott has only 21 of his drawings from his very extensive collection on show, selected by the curators from Leighton House from a shortlist of 120 drawings that Scott gave to them. These choices provide a glimpse into Scott's collection and his personal interests. While it gives a fair indication of the diversity of his collection, it doesn't really provide a true reflection of the richness of his holdings to which those of us who have had the pleasure of seeing the collection in situ can attest. On a modest budget, but with a connoisseur's eye and a vast knowledge of British nineteenth-century art, Scott has managed to put together his remarkable collection. Despite only twenty-one drawings being in the show, and the curators purposely choosing not to pick works by artists already well represented in the French collection like Burne-Jones and Leighton, Scott's collection highlights its scope with examples by early Victorian artists like E. M. Ward, George Richmond, and F.R. Pickersgill, well-known mid-Victorian artists like J. E. Millais, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, John Brett, Arthur Hughes, William Blake Richmond, and Simeon Solomon, and by the Last Romantics like J. W. Waterhouse, Frank Cadogan Cowper, Frank Dicksee and Henry Arthur Payne.

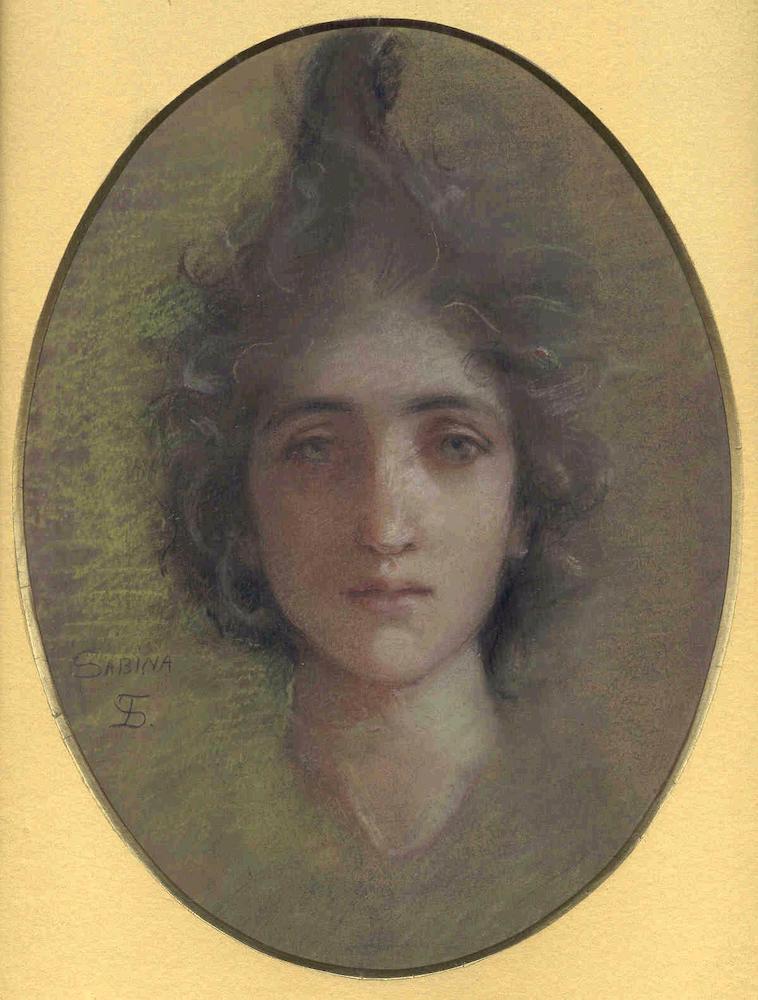

The show even included two artists with whom I was unfamiliar - Eva Ada Spurway and Alma-Tadema's studio assistant James John Gaul. In my opinion the "star of the show" was a pastel entitled Sabina of c.1888 of the head of a girl by Lisa Stillman, the daughter of William Stillman and the step-daughter of Marie Spartali Stillman. Other favourites included Frederick Richard Pickersgill's watercolour sketch for The Industrial Arts in Time of Peace, of c.1871, George Adolphus Storey's First sketch for "Mistress Dorothy" of c.1872, and Anna Lea Merritt's Study for Eve, of c.1885.

Left: Lisa Stillman's Sabina of 1888. Right: Frederick Richard Pickersgill's watercolour sketch for The Industrial Arts in Time of Peace, of c.1871. Both courtesy of the Scott Thomas Buckle collection.

In addition to the quality of the drawings on display another reason why visitors to the exhibition will find this show to be of interest is the range of drawing techniques represented – pencil, pen and ink, ink and wash, chalk, pastel, watercolour and gouache. An art historian could very easily give a seminar on Victorian drawing methods just based on these twenty-one works on display.

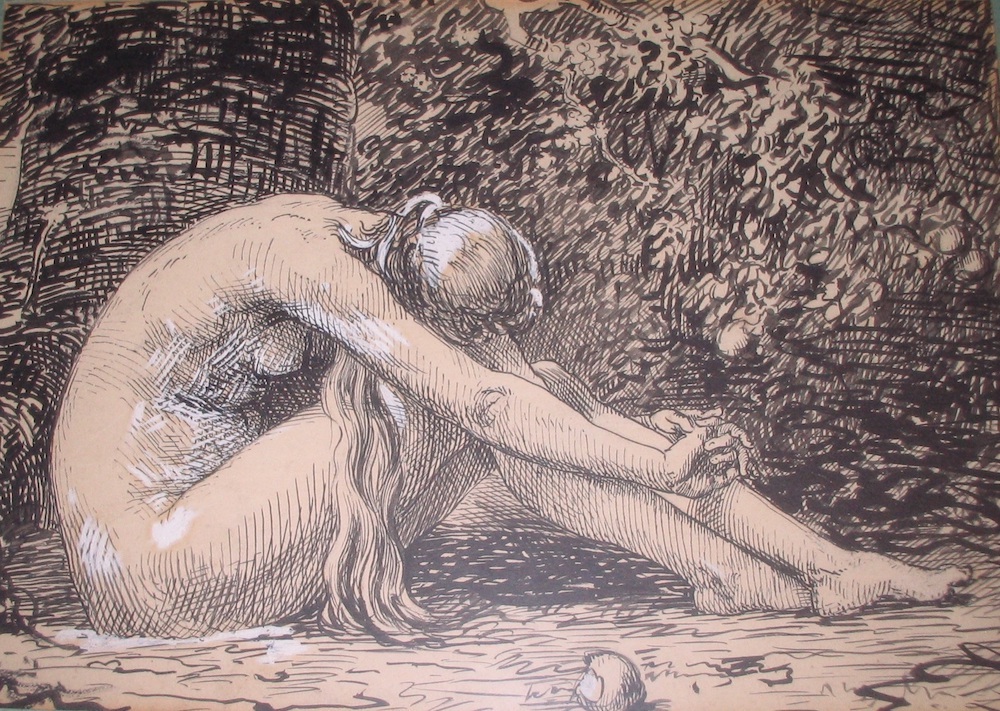

George Adolphus Storey's First sketch for "Mistress Dorothy" of c.1872, and Anna Lea Merritt's Study for Eve of c.1885.

About the only thing missing is a metal point drawing. The selection also gives a good indication of the range of reasons for artists making drawings in the first place, from working studies for major paintings or illustrations, portrait drawings, caricatures, to finished drawings for their own sake. It was instructive to see two examples of juvenilia done by J.E. Millais, sketches of Epsom Derby made from memory, when he was a child of twelve, to get an idea of his precocious talent.

A visit to the Leighton House Museum is always worthwhile, even just to see its permanent collection and the splendour of the Arab Hall, but the chance to see works from these two private collections and to gain insights into the unique qualities of each is an added incentive. I hope anyone with an interest in Victorian art will take the opportunity to visit if they can come to London while the exhibition is running.

Bibliography

Christian, John. Beauty Never Fails. Pictures by Sir Edward Burne-Jones and other romantic artists from the Cecil French Bequest. London: Fulham Palace, 2008.

Created 4 June 2025