Editor’s Note

The following discussion of the Pre-Raphaelites forms the thirty-ninth and last chapter of A Century of Painters of the British School (1890) by the Royal Academician Richard Redgrave and his brother Samuel. In creating this web version, I have added links and images of works mentioned and followed the house style of the Victorian Web, italicizing titles of books and paintings.

This account of the movement has value for a cultural historian because it presents a late-nineteenth-century view of Pre-Raphaelitism, and one, moreover, by a member of the Royal Academy. It also has the virtue of being one of the few nineteenth-century discussions of the Pre-Raphaelites that recognizes the prime importance to the members of the Brotherhood of the paintings of Memling and Van Eyck — that is, of Northern Renaissance artists and not the Italians before Raphael. At the same time, it makes a number of major misinterpretations and omissions. For example, it not only fails to distinguish between the early hard-edge symbolic realism of the Brotherhood and the later so-called aesthetic Pre-Raphaelitism of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones but it also doesn't even mention Sir John Everett Millais, the most skilled and most famous of the original Brotherhood, or Burne-Jones, the most famous late-Pre-Raphaelite painter at the time this account was written! Even more bizarre, the Redgraves never mention Ruskin by name — they only mention the Pre-Raphaelites’ “able expositor” — fail to list the original members of the Brotherhood, and insist that J. W. Inchbold was one of “the landscape painters who founded the P.-R. B.”. Like many older accounts of the PRB, it erroneously describes the charismatic Rossetti, who certainly was the inspiration for aesthetic Pre-Raphaelitism, as the driving force in the original Brotherhood. In fact, as Holman Hunt and Millais agreed, they were inspired by the second volume of Ruskin’s Modern Painters with its description of the way Tintoretto combined elaborate symbolism and detailed realism. — George P. Landow

n all schools, individuals from time to time arise who carry some phase of art to a high degree of perfection, and the danger is that their contemporaries and successors neglect to study nature for themselves, and become followers and copyists of the manner or art of these master spirits. When this occurs, the decadence of the school is rapid. The nature of English habits, and the independence of the English character, are in this respect favourable to art progress, since each man loves to think for himself. Had the landscape painters of the past generation been content to follow the manner of Wilson or Gainsborough, we should not have seen the noble works of Turner and Constable. Novelty in aim or treatment seems necessary to art progress. Wilkie, Leslie, and Mulready, with characteristic differences in their art held its great principles in common; their reputation and the beauty of their works gathered around them imitators, while their living influence was in the schools; but, as the half-century in which they had produced their best pictures drew towards its completion, the painters of the rising school abandoned the rules of art which had guided these great landscape and figure painters, and adopted principles apparently the very opposite of theirs.

The poets of the beginning of the nineteenth century had rebelled against the conventionalisms of their predecessors both as to metre and manner, but more particularly as to their choice of subjects. They had reverted to a degree of realism which was then stigmatized as sheer puerility, and severe was the criticism that Wordsworth and his followers had to endure at the hands of critics and reviewers. Yet the rebellion against old forms of thought was on the whole healthy, and when the first reaction had somewhat subsided, it introduced new beauties, with fresher views of life and springs of thought. Music also had its rebels against authority: and art, although with us at a later period, was to experience a movement of the like nature, and to have its outbreak of realism as had poetry. First the young Germans studying their art at Rome, disgusted, no doubt, withtlie tame proprieties of the modern Romans — Cammuccini and his followers, whose art was built upon rules and precedents with little reference to nature and truth — broke loose from the fetters of the schools.

So earnest were these young artists in following the religious art of the early Italians, which they considered defiled by the Paganism of the Renaissance and despoiled of all fervour by Protestantism, that, headed by Cornelius and Overbeck they went over in a body to the Church of Rome, and henceforth devoted themselves to the restoration of religious art on the basis of its pre-Raphaelite practice. Later the movement spread to France, but under a different phase; Courbet and his followers adopted realism, repudiating beauty and selection, and copying nature as she is found, rather in her meanest than under her noblest aspects.

About the year 1850, seven young Englishmen, five of whom were artists just completing their studies, banded together under the name of the pre-Raphaelite Brethren; a term which they adopted to signify that henceforth they would take their stand on the art of the painters prior to Raphael, as opposed to the conventional art, as they termed it, of his school and followers. They began by publishing a weekly magazine called The Germ, intended to set forth their peculiar views in art and poetry. Though it is difficult to find any clear statement of what these views were, originality and truth seemed to be pointed at in the verse which accompanied the first number, and which was printed as a motto in black letter upon the wrapper; it is as follows: —

When whoso merely hath a little thought

Will merely think the thought which is in him —

Not imaging another's bright or dim.

Not mingling with new words what others taught.

When whoso speaks, from having either sought

Or only found, will speak, not just to skim

A shallow surface with words made and trim,

But in the veiy speech the matter brought;

Be not too keen to cry, 'So this is all! —

A thing I might myself have thought as well

But would not say it, for it was not worth!'

Ask, 'Is this truth?' For is it still to tell

That, be the theme a point, or the whole earth,

Truth is a circle, perfect, great or small! "

If the publication had contained nothing more intelligible than the verse which heralded it into the world, there had been need of little wonder that its career was ended after the fourth number. This, however, was not the case, since some of the contributors gave promise which their pens have since fully redeemed. Still it is to their own statements at the time, and to the works they produced in the first fervour of their brotherhood, that we must look for the principles of the school; unless so far as we may accept them from the pen of one who has ever been their eloquent, if at times, their injudicious champion. Their first great principle was truth rather than beauty; and, therefore, non-selection in treating their subjects. Thus it was said by their able expositor, in his lectures on architecture and painting delivered at Edinburgh, 1853, that "pre-Raphaelitism has but one principle, that of absolute uncompromising truth in all that it does, obtained by working everything, down to the most minute detail, from nature, and from nature only. Every pre-Raphaelite landscape background is painted to the last touch in the open air, from the thing itself. Every pre-Raphaelite figure, however studied in expression, is a true portrait of some living person. Every minute accessory is painted in the same manner." Further that the pre-Raphaelite disciples rejected "that spurious beauty whose attractiveness has tempted men to forget or to despise the more noble quality of sincerity; " and also with the further uncomplimentary addition, that, "in order to put them beyond the power of temptation, they are, as a body, characterized by a total absence of sensibility to the ordinary and popular forms of artistic gracefulness."

It would appear that the protest of these young painters — and it was so far a right protest — was against worn-out conventionalisms, stale repetitions of other men's modes of thought and modes of treatment; although at that time such art was not particularly characteristic of our school. In the spirit of youth and enthusiasm this protest was, in some of their number — for the seven original members soon had a large following — accompanied by an indiscreet self-assertion, and an amusing despisal of all art since the end of the fifteenth century, calculated to call forth some bitterness in contemporary criticism. But on the whole it has had a good result, and art has benefited by their earnestness, and by the works they have produced; even if these have been achieved rather by overlooking their own early dogmas, than by rigidly enforcing them. The three principles which have been enunciated in the above quotations, and which are found in the first works of the brotherhood are: — The rejection of beauty, or non-selection; imitative finish of the details from nature; and equal completion of all parts of the picture. We are told that their first object is truth. " What is truth?" was mournfully asked by one who did not clearly see his way between two conflicting courses; and we may still say, what is truth? Each may decide, as he believes sincerely, but his decision will be warped by his education and his prejudices. We are also told that in pre-Raphaelite pictures each figure is a true portrait of some living person. Now as to this being one of the Pre-Raphaelite efforts after truth, are not all artists accustomed to work from models? When the great Leonardo wished to paint into the "Last Supper" the head of Our Lord, he was for months seeking a model whose head might suggest to him features that he could clothe, alas! he knew how faintly, with the deep impression of Him who sat at meat. Surely this was a right step on the part of the painter in his search after truth. Far more so than was his, who, painting the husband of the blessed Virgin, chose a mechanic with corny hands and sun-stained arms as a true representative, because, like the holy man of old, he was a carpenter; rather than sought out one, whatever his rank of life, whose features might somewhat realize the noble and trustful nature of him who was to shield and shelter from the distrust and scandal which were likely to be her lot, the mother of Our Lord.

Then as to backgrounds. Surely in looking at the touching and earnest expression the painter has given to one who seeks to save her lover from danger and death, we do not wish to be called upon to examine how minutely he has rendered, brick by brick, the wall behind her, with its rotten mortar and crumbling surface. We are not to be provoked into admiration, even though assured that it "is painted to the last touch in the open air," from the wall itself. We rest our eyes on the earnest action, the sweet pleading expression of the woman, and feel that attention to the wall would indicate about the same amount of obtuseness on our part, as on his who, invited to see a picture, should turn aside to praise the frame. Or let us look to the landscape painters of this school, carrying out the "one and only principle of absolute and uncompromising truth obtained by working everything, down to the minutest detail, from nature and from nature only." From such a principle, what is the result? certainly not art, but merely topographical truth. As well might the poet, from some hill-top, catalogue the meadows and cornfields, the hedgerows, the villages, mansions, and churches he sees before him, and call it poetry.

Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehosophat. Thomas Seddon. Oil on canvas. Tate Gallery, London. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Rather than criticize the works of the living, let us take the picture of Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat, by Seddon (b. 1821, d. 1856), in the National Gallery, as a type of the class. It is painted by one who travelled far and endured much to produce it, and it is worthy of our admiration for its fidelity, if we cannot praise it for the art it displays. The Jerusalem is highly interesting; but merely for its topographic accuracy. It is a photograph with colour, containing every — even the minutest — detail of the scene: the walls of Jerusalem ssem piled up stone by stone; outside are the few scant houses of the village suburb with their narrow openings to shut out the eastern sun; square in form and with flat roofs, they look like blocks of stone which have rolled down from the arid hills behind, so similar are they in colour to the rocks themselves. There, feeding on the scant herbage of thistle and teazle, painted as if from a hortus-siccus , are the sheep and the goats together; the shepherd, meanwhile, his long gun beside him, lying under a flowering pomegranate. The little patches of soil on the sides of the valley kept up by walls of stone; the olive and fig trees, each are given by number so that the owner of each might recognize his own tree, his own patch of arid earth. The deep blue heaven of unclouded noon is above, the all-penetrating glare below. Jerusalem is before you — Jerusalem as it is — as it may be registered, mapped and catalogued; but the poetry of Jerusalem is not there: it must come, if at all, from our own hearts and not from the picture. The sheep and the goats feeding together may suggest the great day when the angel of the Lord shall come and divide, setting the one on His right hand, the other on His left; the flat housetops in the Valley of Jehoshaphat, His command that on that day they who are on the house-tops shall not go down to find their clothes: but all these suggestions are from within. This is, and is not, the Jerusalem that He wept over: this is, and is not, the valley of decision, wherein the multitudes shall be gathered on that day: it suggests nothing to us but a barren valley, a hill fortress, a place of stones.

It is true we are told of the pre-Raphaelites that "as landscape painters, the principal of that division of them who do not trust to imagination, must, in great part, confine themselves to mere foreground-work; they have been born with comparatively little enjoyment of those evanescent effects and distant sublimities which nothing but the memory can arrest, and nothing but a daring conventionalism portray." Rather disparaging admissions if true. But it is also said" for this work they are not needed; Turner, the first and greatest of the preRaphaehtes, has done it already." Turner a pre-Raphaelite! Turner, who passed his life in studying nature under her varied aspects that his memory of her might be sure; who left us thousands of his studies, yet repudiated the practice of painting his pictures at all out of doors, and would have laughed at the "one principle, the uncompromising truth of working everything from nature and from nature only, painting to the last touch in the open air from the thing itself" Turner a pre-Raphaelite! he who repudiated topographic imitation when it had served his purpose, and made selection of the beautiful and characteristic in nature his principle; idealizing the commonplace of every-day nature, which the laborious idler, painting from "the thing itself," can never do; and adding to it, from the ample stores of his well-filled memory, every evanescent beauty arising from sun and shade, and the thousand changes with which they glorify the common aspect of things!

But if Turner had been a pre-Raphaelite, let us imagine how he would have painted Jerusalem, "the city of the Great King," had he undertaken to realize it on canvas. Let us notice his treatment of Venice, as an instance in point. We many of us know the actual prose aspect of that city of waters; most of us may have seen the aspect realized, the buildings ruled out with precision, the canals with their regular wavelets as painted by Canaletti; but Turner, despising this matter-of-fact view of the city of the sea, realizes to us rather what the poet saw.

The fair city of the heart,

Rising like water-cokimns from the sea,

Of joy the sojourn, and of wealth the mart."

He lighted up her palaces and towers into jewelled richness with the bright rays of an Italian sun, filled her courts with pageants, her canals with rich argosies, her wharves with gondolas draped with broideries of pearl and gold. Had he treated Jerusalem, would he not by his art have clothed her with some of the glories promised to her by the sacred poet? " I will lay thy stones with fair colours, and thy foundations with sapphires, and I will make thy windows with agates, and thy gates of carbuncles, and all thy borders with precious stones" — some such glorious city has he made of Venice. And such, but far more glorious, we long to picture Jerusalem.

Let us pause, however; lest, in objecting to the principles they propounded, or which were propounded for them, we are thought to depreciate the men who held them. Be this far from us. Some of the followers of this school have attained, and are universally allowed to have attained, the first rank in art; and have painted pictures which all true lovers of art must admire. Some have avowedly repudiated the early principles of the brotherhood; and all who have gained eminence have more or less ignored them. We are also willing to admit that the principles themselves have a great value, if not observed to the exclusion of others, in enforcing constant reference to nature and greater imitative truth.

At first the rigid carrying out of the "one principle of non-selection and exact copying from nature" obtained more among the landscape than the figure painters. Some landscape painters there were who assured us that all the landscapes painted prior to their own advent — not even excluding the works of Turner — if preserved at all, would only be so as curious specimens of what in ignorance was aforetime called art, and in order to compare them with the wonderful works of the painters of tlie future. We may well have been amused with such conceit, as we were well convinced that painting landscapes" to the last touch direct from nature," will not produce noble but rather mean art; and that, however useful at the beginning of an artist's career this mode of studying nature may be, it will be dropped by the true artist as soon as he arrives at greater power, and realizes to himself that true art is the representation of common nature.

The guiding spirit in the brotherhood as first formed was Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti, who is usually called by his last two names. He was the second child and eldest son of Gabriel Rossetti, the eminent commentator on Dante and Italian patriot, for many years a professor in King's College, London, and was born in London, 12th May, 1828. He was, perhaps, the most remarkable member of a remarkable family, and it would be a difficult matter to decide whether he is greater in poetry or in painting; at least, it is certain that for both he was specially gifted, and in both he manifests a quite original and unusual force of genius. He joined Gary's Art Academy in 1843, and entered later the antique school of the Royal Academy, but this latter he attended very irregularly, and he never studied in the life school.

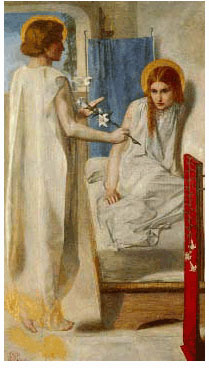

Left: The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. Middle: Ecce Ancilla Domini (The Annunciation). Right: Found [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

After leaving the Academy he was for a while a pupil in the studio of Ford Maddox Brown, and on leaving this painter he joined Holman Hunt in leasing a painting room in Cleveland Street, where he began his first picture (if we except a portrait study of the head of his father), The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. Before this he had written his poem of “The Blessed Damozel” (text of poem), a much more complete work of art than is the picture, which, though a very striking effort for a young painter, scarcely comes up pictorially to what Rossetti achieved in his later works. In this picture, and another very pathetic and dramatic work, called Found and in the Ecce Ancilla Domini now, we are glad to say, in the National Gallery, Rossetti's colour is cold and tame when compared with the splendour and wealth of rich colouring displayed in The Bride, Dante's Dream, Venus Verticordia, and other pictures, but these early pictures, notwithstanding angularity of form, show a purer conception and more sincere earnestness and greater dramatic simplicity of subject than do his later works, which are marred by mannerisms and peculiarities.

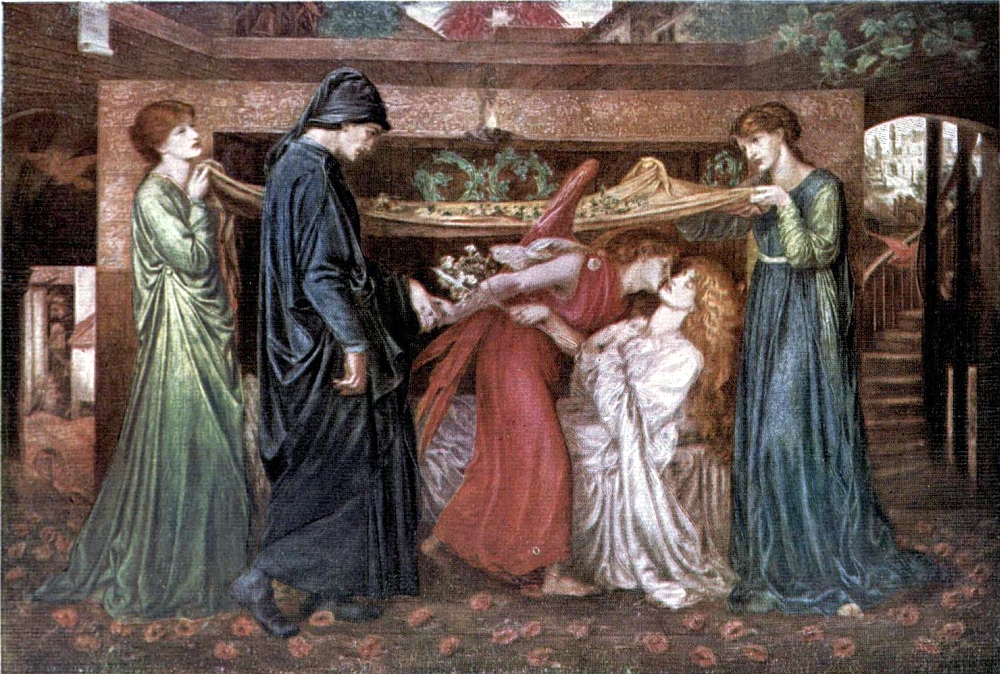

Left: Beata Beatrix. Right: Dante's Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

On the proceeds of the sale of this first picture Rossetti went for a short time to two or three old Belgian towns, where the works of Memling and Van Eyck had a great effect upon him. On his return from this trip, while he was painting in Newman Street, the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was first formed, and its principles were enunciated in The Germ. Rossetti at this time was devoting himself more to water-colour than oil pictures, though he considered the latter medium to be the real vehicle for his expression. In 1860 Rossetti married, only to lose his wife after rather over a year's married life. In the first impulse of violent grief he laid the MSS. of all his poems with her in the coffin, and it was not till ten years later that they were exhumed and afterwards published. Rossetti's wife was a most frequent model for his pictures, and we believe his fine picture of Beata Beatrix, though painted after her death, is a very exact portrait. Beata Beatrix is intended to illustrate symbolically the death of Beatrice as related by Dante in the Vita Nuova. Beatrice is in a trance, and seated in a gallery which overlooks the city of Florence, her figure is life-sized, and about two-thirds is represented on the canvas. The face is quiescent, the hair of a rich auburn. She is dressed in a green bodice with purple sleeves. In front of her is a sun-dial, a crimson bird is bringing her a white poppy, an emblem of the sleep of death, and behind her Dante and the Angel of Love are shown watching in the background. This is one of Rossetti's best works, though for gorgeous colour we prefer The Bride, the subject taken from the Song of Solomon; a group of five female figures round a centre one, the bride, dressed in a robe of figured green, one of the most lovely of Rossetti's female figures, whose beauty is set off by a swarthy young negress in the front of the picture holding up a golden vase full of pink and yellow roses. Dante's Dream illustrates another passage from the Vita Nuova — Beatrice lying dead upon a couch, before which two green-clad ladies hold the pall full of may-bloom. Dante in a dream is led into the chamber by the winged figure of Love in red drapery. The picture is full of poetic details of imagery. It was bought by the corporation of Liverpool.

In about six months after his wife's death Rossetti removed to the house where he passed almost all his remaining life, 16, Cheyne Walk, Chelsea (modern photograph); here he lived in a more and more retired manner, latterly only seeing a few faithful and devoted friends. He varied his life by occasional visits to Scotland. Between 1872-74 he passed much time at Kelmscote Manor in Gloucestershire. In 1872 he had a severe illness, though from this he perfectly recovered. It was partly induced by his habit of taking chloral as a remedy against insomnia. The fatal effects caused by a constant use of this dangerous drug are very much to be deplored, it led to a decay of his bodily energies, and gradually a weakening of his constitution. He was again in 1881 attacked by illness, but nevertheless his death came rather unexpectedly on Easter Day, April 9th, 1882, at Birchington-on-Sea, to which place he had removed by his doctor's advice, as he had been suffering from partial paralysis of the left arm. Rossetti's art, by his persistent dislike to having pictures exhibited, could, during his lifetime, only be known to a small circle, if we compare the few people who could see them in his studio, or at their owners' houses, with the numbers of those who frequent an exhibition. It was therefore a pleasure to many when the Royal Academy resolved to include a collection of his pictures with their Old Masters Exhibition in 1883.

As during his lifetime the opinions on his art varied very considerably, so the controversy continued during this exhibition, and it is rather difficult to pass a fair judgment upon it, as we are too near to him to be quite dispassionate in our criticism. Rossetti's art was that of a mystic deeply imbued with the study of Dante, and of the Arthurian legends. He owed nothing to foreign travel, academic study, or to artists in general, for though he was greatly admired by many painters, he was personally known to but itw, and over these he exercised more sway than they did upon him. In the great point of originality, his works are therefore very unique. We have had few artists of such distinct individuality. His pictures betray a decided exuberance of fancy, they are rich and splendid in colour, and in some cases very fine in execution; on the other hand they are apt to degenerate into a wholly sensuous feeling for beauty, they show a lack of drawing or of a want of any appreciation of what is classical in form. He paints too much from the same model, whose too rich lips and large throat he exaggerates and overdoes. His intention is always earnest, and his work is carried through with the same arduous effort of the mind which is apparent in the poetically thought-out details of all his pictures.

He ever strove to realize his ideal. Whether this ideal was as pure and elevated in conception as we should like the ideal of a great painter to be, whether it was not sometimes marred by a passion for a certain kind of beauty not of the highest order, a beauty more sensuous than spiritual or intellectual is a matter perhaps for each person who thinks over the subject to decide for himself. To our mind it detracts from the otherwise high poetic grace and value of Rossetti's work.

Again Rossetti's admirers seem to have a blind partiality for all his art, but we should call him an uneven painter. There is a great difference in his work, and while some of his pictures, such as Found, Dante's Dream, The Blessed Damozel, The Bride, are most powerful creations, there are water-colours by his hand that might have been produced by an inferior imitator of his pictures.

James Collinson, another original member of the brotherhood, but who seceded from it in 1852, was born at Mansfield in Nottinghamshire, 1825, and died in London 24th January, 1881. His picture of St. Elizabeth, which was an illustration of a portion of Charles Kingsley's Saints' Tragedy was painted while he was contributing to The Germ. He afterwards became a Roman Catholic, and in future exhibited pictures of domestic subjects.

Among the landscape painters who founded the P.-R. B. John W. Inchbold was throughout his life the one most influenced by pre-Raphaelite principles. He was born in Leeds in 1830, and died there in 1888 suddenly from heart disease. His pictures were very careful and minute copies of nature, his subjects were chosen apparently without selection, and though his colour was very brilliant and yet delicate, his work was wanting in atmosphere and in sense of proportion. The Moorland, exhibited by him at the Royal Academy in 1855, is perhaps his best picture.

On the whole English art was improved rather than injured by what was called the pre-Raphaelite “heresy,” the zeal and earnestness of its followers served to counterbalance the evil caused by the numbers of meretricious pictures, which the newly-awakened interest of the public in art, the formation of art-unions all over the country, led those painters to produce who only cared for money and who painted with no end but to sell. It is curious that the ebb and flow which seems to obtain in all the circumstances of human life has now apparently washed away the sincere, earnest, and minute endeavour of the pre-Raphaelite after truth, bringing in his place the ardent Impressionist who, though affecting the same zeal for reality, presumes it can only be attained by dash and vagueness, by slashing on masses of untempered colour upon a canvas in any state of unfitness for its reception, and who, though trained in the French school, begins where he ought to finish, and, without the genius of his masters, believes that if he is able to imitate their faults he may count himself a sharer in their perfections.

Some time ago, another source of danger to true art arose out of its very prosperity. Rumours of the large sums paid to living artists for commissioned work, the rise of prices in pictures of merit when sold at Christie's and other public sales, was looked upon by painters as a proof that art had a brilliant future for all its members; whereas a more wholesome view to take would have been that the rise in prices came from the general prosperity at that particular time of the middle classes, and from the abundant capital at that moment in the hands of our large manufacturers, who, unlike our nobles with large estates, family encumbrances and numerous dependents, had but to spend or re-invest their gains. Art affords both these opportunities; it gives pleasure and delight in possession, and rising prices show that the best art is a safe investment. But how obtain the best art? Want of knowledge on the part of the purchasers has raised up a class of middlemen and dealers; these again add largely to prices for their necessary profits. It would be wrong to say that many of this new class of purchasers were not genuine lovers of art, or that those who began with small knowledge or appreciation, did not learn by possession of fine works to love art for its own sake.

Still, with the many, art is no more than a source of self-glorification in possession, and a safe and improving investment for the future. The true painter should resist the spirit of covetousness. It is right that artists should be paid at least as well as other professors who require no higher endowments, no longer previous study, nor harder probation ere reputation is achieved, than those who, if they are true artists, must also be favoured with natural gifts. But art must be practised for the love of it, and not for gain, if art is to make true progress. The artist should love his labour, and no work should leave his easel that is not the best he can make it. This is hard, when dealers and purchasers wait, money in hand, hungry for possession, and caring little for subject or for excellence, so that they get an undoubted work of a favourite painter: hard indeed to resist the temptation of ready profit, though perhaps indifferently satisfied with the success of his own labours. Thus the very prosperity of artists may be a source of danger to true artprogress. There are other causes that may affect the future of art, either for its prosperity or decay. We have shown its progress, from small beginnings until it is almost co-extensive with society. Some knowledge of it has spread among all educated classes, the Government taking in hand, as we have shown, to instruct the artisans, and even their children, in its rudiments.

Three of the art institutions mentioned by the Redgraves. Left: Hampton Court. Middle: . Right: The first-constructed portion of the Victoria & Albert Museum [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

At the beginning of our history, one exhibition of modern works was a novelty; now all classes have opportunity of seeing not only modern pictures, but the noblest works of art. The National Gallery opens its treasures, not to the rich alone, but freely to the poor; Hampton Court is the resort of the poor man on his holidays; South Kensington in his leisure hours. The great International Exhibitions have afforded means for the multitude to see and enjoy the best modern art of all countries. The winter exhibitions of the old masters now held in London bring the fine works of bygone art before the public. Illustrated works issue from the press at prices within the reach of all; and so the workman has learnt to love art, and has had it brought near to him by various societies.

During the latter pairt of our century, hopes have been realized which were the life-long dreams of our predecessors. Our early academicians offered to devote to them their unpaid labours. Barry struggled through life in an endeavour to realize them. Haydon saw these hopes at the point of realization, and died. Our churches even have opened their doors to the painter, and works have been produced that may well vie with anything that has been done in m.odern times in other lands. It remains to be seen whether this step in art-progress will be continued, but our faith is yet strong in the progress of art; we know that the English school has much to achieve, and we do not believe in our brethren flagging in the race. The talent rising up to succeed that which is passing away is abundant; and, if with a difference, is it not desirable that it should be so? All originality consists in a difference. Even as we write we read in the press the successes of our painters, at the Paris 1889 Exhibition, and though our work does not permit us to mention living painters, we have every confidence that British artists will continue to produce works worthy of record in a future century of painters of the English school.

Bibliography

Redgrave, Richard, and Samuel Redgrave. A Century of Painters of the British School. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1890. Internet Archive version of a copy in the Dorothy H. Hoover Library, Ontario College of Art & Design. Web. 26 November 2014.

Last modified 26 November 2014