irmingham City Art Gallery contains some of the outstanding works of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and its greatest artefacts have recently been on a five-year tour of America in the form of the exhibition, ‘Radical Victorians.’ The Art Gallery has itself been closed for three years, and to mark a partial re-opening the show has returned to its mother-institution.

‘Radical Victorians’ presents 145 objects, made up of paintings, drawings, books, costumes, jewellery, sculpture and other domestic craftworks, and the line-up of makers is impressive. Featuring the original Pre-Raphaelites, D. G. Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and J. E. Millais, it also includes work by associates such as Ford Madox Brown and the second generation of painters who came under the spell of the PRB, notably Simeon Solomon, Edward Burne-Jones – or plain Ned Jones when he lived in Birmingham – Fred Sandys and Arthur Gaskin. The Arts and Crafts workers, William Morris and C. R. Ashbee are also represented in conjunction with others working in the medium of bespoke making.

It’s an overpowering sight: brilliant colours radiate from elaborate gilt frames, and the intense detail of Pre-Raphaelite verisimilitude competes with the abstractions of long-necked beauties and the glittering light of brightly polished silverware. Those with a knowledge of Pre-Raphaelitism will no doubt enjoy the experience of seeing once again the tightly worked surfaces of Brown’s Work (1851) and the reflective look of Rossetti’s figure in Proserpine (1882) as she realizes her fatal mistake, pomegranate still in her hand, the emblematic ivy signalling the workings of memory as the light of the over-world is about to be extinguished. These, and many others, are great works of observation and imagination, the twin poles of Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics, and wonderful to see in one venue.

The exhibition is organized into four main spaces, each with a number of outstanding pieces. The first, which charts the so-called ‘first stage’ of Pre-Raphaelitism, is a vivid representation of the movement’s stylistic gawkiness, with early, medievalist drawings by Millais and Rossetti embodying the Brothers’ attempts to capture the linearity of Quattrocento art as they chart the profiles of love and longing. Millais’s Lovers by a Rosebush (1848) typifies the PRB’s pursuit of formal purity and psychological depth, capturing the delicate moment as the male lover detaches his beloved’s gown from a thorn tendril – a fragile piece of verisimilitude, charged with metaphorical significance. This is magical, poetic imagery, and it is matched by several stand-out pieces. Alexander Munro’s sculpture Paola and Francesca (1852) continues the courtly theme, embodying pure love in its smooth milky surfaces, and equally fascinating are two of Rossetti’s original drawings for the ‘Moxon Tennyson’ (1857). Drawn in brown ink, and significantly different from their appearance as wood-engravings, the illustrations for the death of Arthur and ‘The Palace of Art’ are intricate images of an inner world, stacked with decorative objects and haunted by Elizabeth Siddal’s plaintive features.

Left: Wallis, The Stonebreaker and Right: Madox Brown, Work (this is the copy in Manchester, but is identical with the Birmingham version.)

The rest of the space, divided up within the Gas Hall, is more diverse, with paintings by Arthur Hughes, Millais and Ford Madox Brown. The highlights here are exemplars of the Pre-Raphaelites’ treatment of social themes: Brown’s Work (1852) dominates, with its documentary treatment and celebration of physical labour, but the consequences of work or lack of it are suggested by Millais’s The Blind Girl (1854–56) and Henry Wallis’s The Stonebreaker (1857). Millais’s picture reminds us of how bright Pre-Raphaelite painting could be as we are invited to gaze at a landscape of hallucinatory intensity, the very sight the blind girl cannot see; dependent on her companion, her world is one of helpless suffering. Tougher still is Wallis’s painting, depicting the hard facts of exhaustion in the form of a dying labourer – the very opposite of the athletic road-digger who features in Brown’s composition.

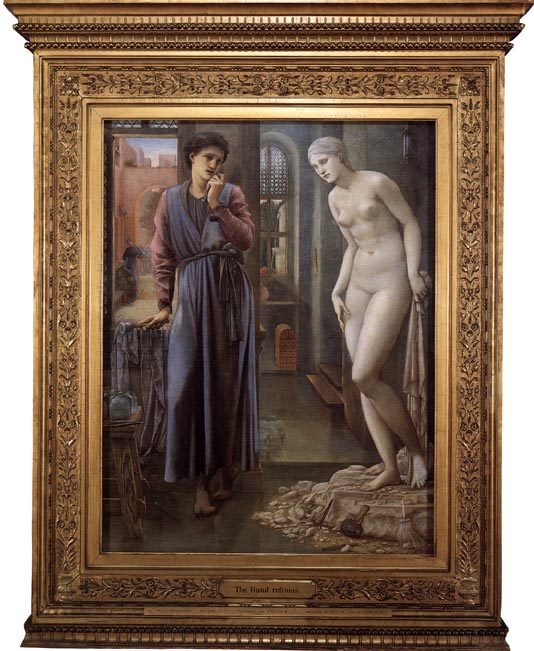

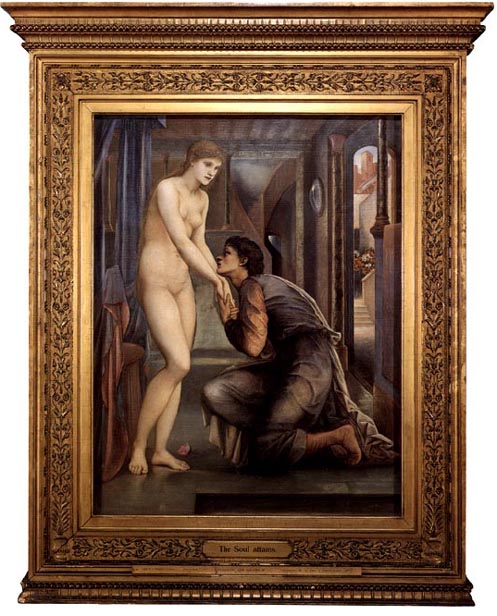

Left: Millais, The Blind Girl; b and c), two of the pictures out of Burne-Jones’s four picture sequence, Pygmalion series.

The second room is concerned with Pre-Raphaelitism’s second stage. Female beauty and art-for-art’s sake are the main themes, with Rossetti’s Proserpine (1882) juxtaposed with androgynous portraits by Simeon Solomon and Frederick Sandys’s murderous femme fatale, Medea (1868), the most dynamic and interesting piece in this section. These images typify the Pre-Raphaelites’ unstable notion of femininity in which gender itself is under investigation. How women were viewed is further suggested in the third space, with Burne-Jones’s Aesthetic Pygmalion series (1875–78) providing a visual summary of the process of creating beauty – or is it merely a reflection on men’s objectification of women? Burne-Jones’s pale and abstracted canvasses are completely passionless, and make it seem as if the sculptor is indeed in love with a piece of marble, and not the woman his sculpture becomes. Art, love, sex, desire and beauty are intermingled puzzlingly, offering a suggestive poetry which could be viewed as either vacuous or profound.

The final part of the exhibition is concerned with Arts and Crafts, with Morris’s ‘Kelmscott Chaucer,’ more like a medieval manuscript than a printed book, placed in conjunction with jewellery by Ashbee and Powell. These artefacts are presented as items in search of a new utopia in which aesthetic ‘improvement’ and the application of handicraft were viewed, so very naively, as a solution for Britain’s social tensions and the degradation of its working classes. Beauty becomes social conscience and aesthetics becomes Socialism, even though the products of the Arts and Crafts movement could only be afforded by the wealthy, so tending to cement rather than subvert the status quo while allowing some privileged individuals to imagine they were neo-medieval craftspeople living in utopia: another paradox. The exhibition finally considers the Birmingham School of Art, which complied with Morrisonian ideals: The Quest, a booklet produced by Arthur Gaskin purely for students at the School, summarizes the Pre-Raphaelite style and its emphasis on the artist as artisan in the final years of the nineteenth century.

‘Radical Victorians’ provides an interesting, panoramic view of all of these themes, and the show’s strength lies in the quality of individual pieces. As an exhibition, however, there is some room for improvement, and it has to be asked if it adds anything to the display of Pre-Raphaelite artefacts when they were exhibited as part of the permanent collection. From the viewer’s point there are unquestionably some uncertainties, with the exhibition occasionally missing its mark.

Some of its confusion is to do with the definition of the term ‘Pre-Raphaelite,’ which is never once spelled out in any of the thinly written and underwhelming information boards. The impression conveyed by the organization of the works misleadingly suggests that all of the artists were part of a coherent group, even though most of them were associates rather than members of the original brotherhood, or artists working in the Pre-Raphaelite idiom. That distinction is not made clear.

Nor is it clear, a little more damagingly, what ‘radical’ is intended to mean in the present context. For sure, the Pre-Raphaelites and their successor movement were ‘radical,’ but in what sense? The exhibition doesn’t meaningfully attempt to define the precise ways in which the artists challenged the status quo in terms of their development of new artistic codes as they engaged with social issues. These types of radicalism are implicit in the selection of works, but never directly addressed, and some selections are plainly misleading. I am thinking of the opening two canvasses, one by David Cox and another by William Etty. The implication is that the Pre-Raphaelites moved on from this sort of painting, but in fact both artists were admired by the original Brotherhood: what the original seven disliked were the ‘sloshy’ brown canvases of Sir Joshua Reynolds and the sentimental productions of Victorian third-raters. That type of positioning is badly needed, and the absence of accurate framing places the show on a dodgy footing. The viewer is left to consider the paintings and craft works as progressive and ground-breaking, but with little sense of how to measure their progressiveness.

What we have, instead, is a representative cross-section of what Pre-Raphaelitism looked like, its heterogeneity, its inconsistences and, on several occasions, its weird incongruity. Nevertheless, ‘Radical Victorians’ offers a chance to study some famous works after an absence of some years. The show is billed as a return, and, whatever the shortcomings of the present exhibition, it is a homecoming to be cherished.

Links to Related Material

- Review of the catalogue of the exhibition

- The First Pre-Raphaelite Group Exhibition

- [A Review of] Pre-Raphaelite Treasures: Drawings and Watercolours from the Ashmolean Museum at the Watts Gallery, Compton, 8 March - 12 June 2022

- [A Review of] "Pre-Raphaelite Sisters" at the National Portrait Gallery, London, 17 October 2019 – 26 January 2020

Created 15 February 2024