Except for the first one, illustrations come from our own website. [Click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.]

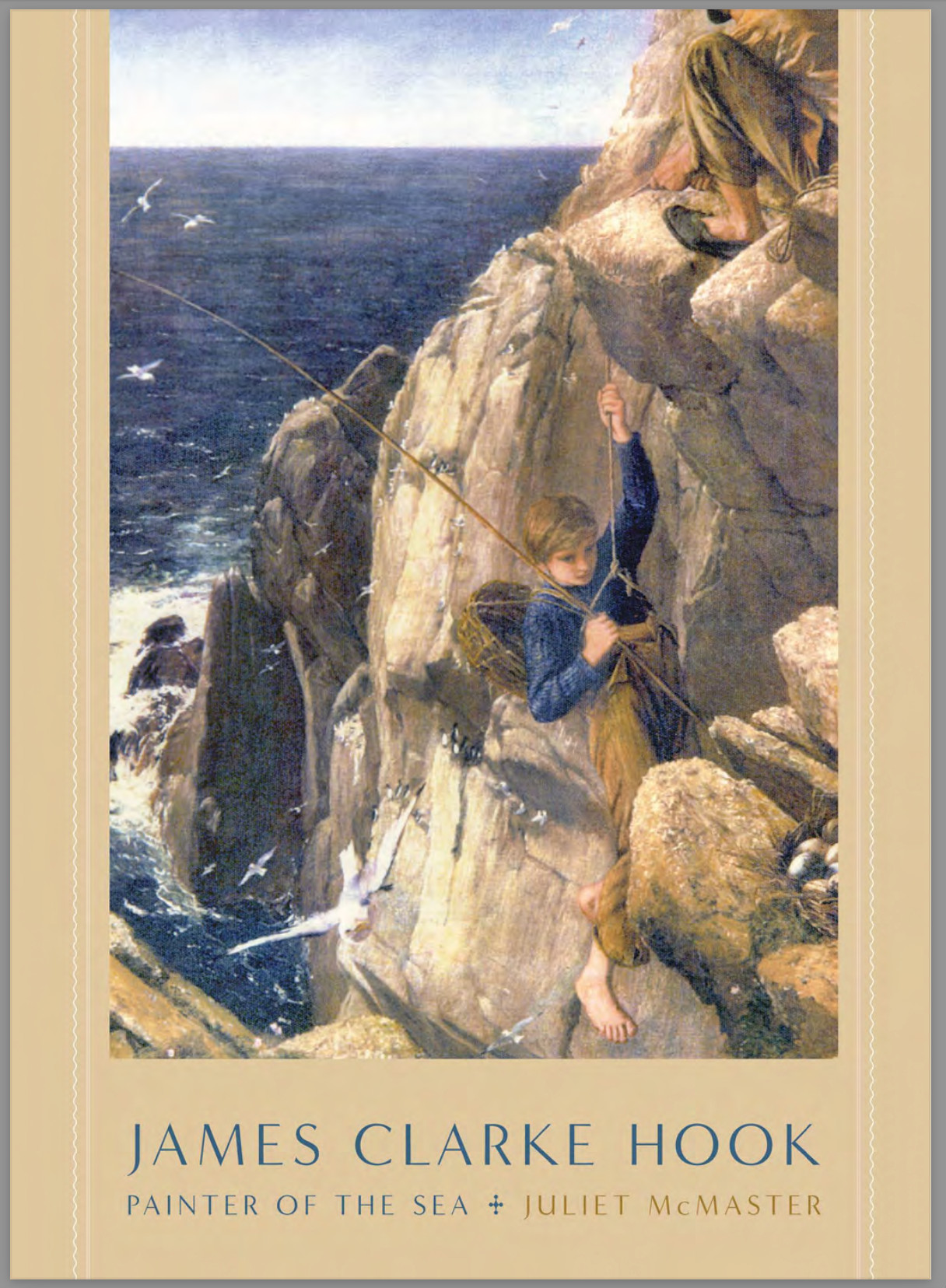

Cover of the book under review, featuring The Coast Boy Gathering Eggs (1858), "painted on Lundy Island off the north coast of Devon" (113).

Victorian painting has an enthusiastic following these days, yet some of the most successful Victorian artists are still undervalued. Their reputations have been eclipsed by the greater fame of a few big names, notably Turner, Millais, Rossetti (and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in general), as well as by such distinctive groups of the later decades as the Newlyn School in Cornwall. James Clarke Hook (1819-1907) is a case in point. The eldest in a family of ten, he was encouraged by his father and sponsored for entry to the Royal Academy Schools by Constable, who seems rarely to have performed such a service. His Professor of Perspective there was Turner himself, and the fledgling artist acquitted himself well, winning the Schools' coveted Travelling Scholarship. His painting career developed apace. Naturally, he was touched by the major developments of the time, especially, at the stage when the central figures of the Brotherhood were all setting out together, Pre-Raphaelitism: "his principles and practice in painting at this time were quite close to theirs, and when the Brotherhood drew hostile criticism, he was their staunch supporter" (86). But he was finding his own way forward, and this perhaps helps to account for his relative neglect in our own times.

Two early works. Left: A costume piece: Pluming the Helmet (c.1852). Right: A landscape on a literary theme: "Colin thou ken'st, the Southerne Shepheard's Boye" (1854), inspired by Edmund Spenser's The Shepheard's Calendar.

For some years, in the second half of the 1840s and the early 1850s, Hook focused on history painting, in which he had excelled at the Academy Schools. In the "Italian Sojourn" of 1846-48, his extended working honeymoon after winning his travelling studentship and getting married, he took particular interest in Italy's historical and literary associations. Both he and his wife Rosalie, an artist herself, did a great deal of copying in the art galleries and sketching of local sights, the former often for commissions. McMaster traces the Hooks' adventures here in a thoroughly enjoyable way, with relevant mentions of other expatriates and visitors to Italy at this time, such as the sculptor John Gibson, whose studio they visited in Rome, the Brownings, married a few months after them in 1846 and now living in Florence, and Dickens, whose ascent of Vesuvious predated theirs. Hook's own inclination at that time can be gauged from the subjects he chose for his Academy offerings of 1847 and 1848: a scene from The Merchant of Venice, entitled Bassanio Commenting on the Caskets (1847), and a painting on the subject of Emperor Otho IV (1848), now "lost to sight" (81).

But one part of McMaster's account of the Italian trip stands out:

Although they did not yet know it, the Hooks were nearing the end of their stay in Italy — they had only January, February, and March in Venice — but in many ways, this time was the most important for James, and provided the most lasting legacy for his career.

The weather remained cold and wet. When they looked out in excitement on their first morning, wrote Rosalie, “We could see nothing but water above and below." Perhaps it was the Venice impress that lasted through Hook’s career, for “water ... below,” at least, pertains in the majority of his paintings. The sea, of course, was to dominate his work from 1856 onward; but even his landscapes nearly always have a body of water in them, with translucence and gleaming surfaces. He came to depend on a light source below as well as above, as there is in Venice with its lagoon and reflecting canals. [68]

Hook's next Academy exhibit, Othello's First Suspicion (1849), was again on a literary theme, but the one he showed that same year at the British Institution, entitled simply Venice is a medieval scene of a couple in a gondola, which pays homage to the city that was now inspiring him. However, his "sea-change," as McMaster puts it, was by no means immediate. For the time being, he was doing well with his historical subjects. From 1850, as a young A.R.A., he became an established part of the artistic set at Campden Hill — in fact, he was the first to build his house there, two houses to be precise, named Tor Villas. The couple's first son, Allan James Hook, was born at No. 1, Tor Villas in 1853. The young family would now enjoy excursions to various painting sites in Surrey and further afield, and when Rosalie recorded the birth of their second son, Bryan, in the summer of 1856, she added, "we were at Clovelly soon afterwards" (109). The works painted on location there, on the Devon coast, were greeted, as McMaster shows, "ecstatically" (106), not only by his close associates, but even, most gratifyingly by John Ruskin.

A more typical work, of the kind dubbed "Hookscapes," featuring children. Word from the Missing, 1877.

Hook and his family moved out of the Tor Villa house in 1857, renting it to Holman Hunt, while they themselves settled into a rural way of life in Surrey. This was what Hook had longed for, and he enjoyed landscape painting in this pretty part of the world, almost as an indulgence, while he now painted "for other people" the kind of coastal scenes that had had brought him such acclaim (157). He was elected RA in 1860.

Eventually dubbed "Hookscapes," the new works literally made his name. This was well before the colony of seaside painters at Newlyn started attracting attention in the 1880s. His works, in fact, foreshadowed theirs, in that their appeal lay not only in the sea itself, but in the human element. McMaster's opening chapter had explained a good deal about Hook's character. His father, who had been bankrupt once, and was later based in West Africa dealing with the aftermath of the slave trade, had instilled in his eldest son a strong sense of family responsibility. A loving husband, father and later grandfather, Hook never lost his caring nature. It can be seen in his portraits of children in these coastal scenes, often based on his own children and grandchildren, and indeed in his "genuine sympathy and respect for the working people he depicted" (193). Such empathy was reinforced by his way of life when painting away from home: the Hooks, says McMaster, "lived lives as hard and as simple as the fisher families who peopled his canvases" (193). Other painters, as McMaster has already pointed out, tended to be "either landscape painters or figure painters" (104), but Hook had the skill and generosity of spirit needed for both. It was a winning combination. So popular did he become that Rosalie remarked on one occasion in May 1874, "It would take Mr Hook many years to fulfil all the commissions which he has" (qtd. 155).

There was more variety in Hook's work than is commonly realised — witness this fine self-portrait painted at the age of 76.

In telling Hook's story, McMaster, the granddaughter of one of Hook's two artist sons, opts for a largely straightforward biographical progression, from Chapter 1 ("The head .. of ten") about his family background and childhood, through the various phases of his life as a painter, to the ninth chapter on "The veteran Mr Hook" — except for an interesting and more wide-ranging chapter (6) about the Etching Club, of which, like Millais and Hunt, he was a long-time member. There is a sense here of pride in a creditable family history, which, together with scholarly research into her ancestor, makes for a very appealing reading experience. Some comparison with other renowned sea painters of the age, like Clarkson Stanfield (1793-1867), Henry Moore (1831-1895) and Peter Graham (1838-1921), and more about the rise of land- and seascapes in general, would have been welcome, especially as context for what McMaster calls "the progressive retreat of the figures" in Hook's later work (184); but no one deserves celebrating more, both for his achievements and humanity, than this gifted painter. McMaster has done him (and us) a great service in writing this lavishly illustrated book about him.

Bibliography

McMaster, Juliet. James Clarke Hook: Painter of the Sea. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2023. ISBN: 978-0-2280-1445-4

Created 28 September 2023