This essay first appeared in the 1984 Browning Institute Studies: An Annual of Victorian Literasry and Cultural History. (1) Numbers in brackets indicate page breaks in the print edition and thus allow users of VW to cite or locate the original page numbers. (2) Where possible, bibliographical information appears in the form of in-text citations, which refer to the bibliography at the end of each document. (3) Non-bibliographic notes appears as text links. [GPL].

ictorian writers and artists gazed at the phenomenon that was Rome and found in it what they wanted and needed to find. Rome cast a longer shadow than did the Bible on the British upper and upper-middle classes, for whom Latin was a second language and Roman history a second past. The Bible's influence pervaded the culture of the classes below them, many of whose members had learned to read precisely in order to read the Scriptures according to evangelical interpretive and meditative practice. Since many individual members of the lower and middle classes rose in power, wealth, and social position during the Victorian period, cultural attitudes based on the Scriptures came into conflict with those based on the classical past. But for those in power, Rome and its grand, diverse, tortured, ambiguous history remained the predominant cultural example, though at times notions of chivalry and Hellenism rivaled its influence (see bibliography for books by Giraud, Jenkins, and Turner).

Because Rome had such a long history, one has to point out that "Rome" in the nineteenth century meant not only classical Rome but also the medieval city and the contemporary one as well. William Holman Hunt's Rienzi (1849), whose subject was drawn from Bulwer-Lytton's novel of the 1830s, exemplifies a self-conscious use of medieval Rome to provide a pattern or at least relevant commentary on contemporary England and its concerns. Hunt's painting portrays the young scholar's conversion to political life — a particularly apt subject for a young artist in 1848. After rival factions among the nobility kill Rienzi's younger brother, an innocent bystander, in one of their [29/30] brawls, he swears vengeance; and to achieve his goal, he must destroy the present order. Like so many reformers before him, he turns to the example of ancient Rome and becomes a tribune, or representative of the people's rights. Hence the novel's subtitle, "The Last of the Tribunes." According to Bulwer-Lytton's novel, which he reissued in 1848, a time of revolution, the scholar Rienzi was a true patriot and proto-Protestant reformer who briefly and heroically brought justice, order, and power to the tyranically misgoverned people of Rome. Hunt's painting and Bulwer-Lytton's novel, its source, thus doubly draw upon the history of Rome to instruct their contemporaries politically. Even though the novel is set in medieval Rome, the classical past dominates, since the office of the tribune who defends the people's interests derives from the ancient city.

In contrast to Bulwer-Lytton's and Hunt's political emphasis, George Eliot's Middlemarch presents Rome as the embodiment of cultural traditions that threaten and disorient one brought up solely on the culture of the Bible. When Dorothea Brooke encounters Will Laidislaw and Naumann, the Nazarene painter who paints her portrait, she also encounters a challenge to her narrow, culturally starved evangelicalism from this ancient home of the arts, artists, and artistic traditions. "After the brief narrow experience of her girlhood she was beholding Rome, the city of visible history, where the past of a whole hemisphere seems moving in funeral procession with strange ancestral images and trophies gathered from afar." Eliot's narrator explains the way a "stupendous fragmentariness" afflicts Dorothea, whose sensitivity opens her to an assault against which her meager knowledge and experience cannot protect her:

To those who have looked at Rome with the quickening power of a knowledge which breathes a growing soul into all historic shapes, and traces out the suppressed transitions which unite all contrasts, Rome may still be the spiritual centre and interpreter of all the world. But let them conceive one more historical contrast: the gigantic broken revelations of that Imperial and Papal city thrust abruptly on the notions of a girl who had been brought up in English and Swiss Puritanism, fed on meagre Protestant histories and on art chiefly of the hand-screen sort; a girl whose ardent nature turned all her small allowance of knowledge into principles, fusing her actions into their mould, and whose quick emotions gave the most abstract things the quality of a pleasure or pain. . . . The weight of unintelligible Rome might lie easily [30/31] on bright nymphs to whom it formed a background for the brilliant picnic of Anglo-foreign society; but Dorothea had no such defense against deep impressions. Ruins and basilicas, palaces and colossi, set in the midst of a sordid present, where all that was living and warm-blooded seemed sunk in the deep degeneracy of a superstition divorced from reverence; the dimmer yet eager Titanic life gazing and struggling on walls and ceilings; the long vistas of white forms whose marble eyes seemed to hold the monotonous light of an alien world: all this vast wreck of ambitious ideals, sensuous and spiritual, mixed confusedly with the signs of breathing forgetfulness and degradation, at first jarred her as with an electric shock, and then urged themselves on her with that ache belonging to a glut of confused ideas which check the flow of emotion. [Book 2, Chapter 20]

Dorothea thus encounters Rome, a city whose history and monuments provide a counterbalance and challenge to the religious culture that has guided her thus far in her young life. Eliot, in other words, presents Rome as something so powerful, so complex, and so alien that her Bible-centered attitudes turn out to be insufficient to take it all in. Rome remains indigestible, uninterpretable.

Robert Browning also presents the clash of Rome and evangelical Protestant thought, but in The Ring and the Book the Bible triumphs in such a way that he can still take the ancient city, in Eliot's words, as "the spiritual centre and interpreter of the world," but only because his interpretive methods place it within the biblical world-view. The Ring and the Book reveals Rome come to be the universal city, a representative human community in which one encounters all the good and evil that make up the human condition. Browning's poem of many perspectives and vantage points is set in the seventeenth century, and the poet explores a controversial murder to probe certain universal concerns, including the role and explanation of evil in the world, the nature of virtue and heroism, and, most important, the role of the poetic imagination in attaining a living knowledge of truth. The center of all the poem's many ambiguous concerns is a hermeneutic one, for Browning has written an elaborate interpretive exercise to convince the reader that his interpretations are correct. Like Ruskin, Hunt, and Hopkins, he models his symbolic methods, theories of the artist, and interpretive rules upon those of typological exegetics, and he devotes considerable attention to demonstrating the proper way one must interpret the world. The Pope, Pompilia, and Browning's speaker all exemplify proper uses of such interpretive approaches, while [31/32] Guido and the lawyers reveal skilled, if completely erroneous applications. One of the counselors sums up the conflict of Rome and the Bible by arguing from classical myth, which the poet then subsumes within his overall reading of the events surrounding Pompilia's murder.

To many Victorians, particularly evangelicals, Rome meant the seat of Roman Catholicism and as such a modern Babylon. When the Pope chose to reinstate the lapsed Roman hierarchy in 1850, Englishmen reacted with cries of "papal aggression," but the Oxford Movement in the previous decade had already prompted an entire literature of pamphlets, poems, and novels in which Rome appeared as either the thirsty soul's earthly paradise or the unwary or corrupt one's infernal abode. Novels like John Henry Newman's Loss and Gain (1848), Nicholas Wiseman's Fabiola; or, The Church of the Catacombs (1854), and Lady Georgina Fullerton's Grantley Manor (1847) present the Eternal City as the city of God, whereas Grace Kennedy's Father Clement; A Roman Catholic Story (1823), Frances Trollope's Father Eustace (1847), and William Sewell's Hawkstone (1845) argue that it is the city of His chief adversary; see Wolff, pp. 27-107, for a discussion of these polemical fictions. Newman's Apologia Pro Vita Sua (1864), which makes his own movement from Oxford to Rome an exercise in retrospective interpretation, tries to show how the truly religious English believer inevitably must tread the path to that spiritual city.

Throughout the period a literature of religious polemic — sermons, tracts, even novels and hymns — had urged the contrary reading of Rome, and occasionally one encounters writers who are patently not ultra-Protestants employing them. A related hostile image of Rome appears, for example, throughout Swinburne's political verse. Because the Catholic Church supported the foreign occupiers of Italy, Swinburne, who set himself up as the poet of the Risorgimento, continually attacked it. In "Locusta," for example, he likens the Church of Rome to a poisoner infamous in the time of Nero and Claudius:

Lo, the lips

That between prayer and prayer find time to be

Poisonous, the hands holding a cup and key,

Key of deep hell, cup whence blood reeks and drips. ...

With the old hand's cunning [she] mixes her new priest [32/33]

The cup she mixed her Nero, stirred and spiced.

She lisps of Mary and Nazarene

With a tongue tuned, and head that bends to the east,

Praying. There are who say she is the bride of Christ.

Swinburne's combination of images drawn from classical and Christian Rome for this particularly nasty satirical image reminds us how difficult it was for an educated Victorian to avoid the shadow of classical Rome, and in fact although there are a surprisingly large number of Victorian works that concern themselves with the post-classical city, Rome still chiefly meant ancient Rome to most Victorians. In the following pages I therefore plan to look briefly at some literature and paintings that attempt to illuminate the concerns of the Victorian world by looking back at classical Rome. Of course, Western Europe has long had a tradition of turning to ancient Rome for precept and example by which to guide its own systems, just as the Italian city-states of the Renaissance picked and chose which facts of Roman history they wished to emphasize and thus justified alternatively monarchy or democracy. Depending upon the kind of government in force in one's country, a Renaissance Italian could have emphasized the virtues of either Caesar or his assassins, Imperial or Republican Rome. Revolutionary America and France both used the tradition of the Roman Republic to justify themselves, and would-be emperors from Charlemagne to Napoleon, Hitler, and Mussolini similarly invoked the particular idea of a Roman past that appealed to them. Such self-conscious uses of Roman history as either political mirror or political lamp also occur in the age of Victoria, but a far different, though no less polemical, application of the past to the present characterizes nineteenth-century uses.

After looking at several examples of Victorian uses of classical Rome for political paradigms, I shall suggest some other ways the Roman past appeared in hopes that it would form or inform the Present. Thomas Babington Macaulay's The Lays of Ancient Rome (1842) reminds us that men of the nineteenth-century, like those of earlier ages, often looked to the history of Rome for political action and ideals. The historian's most unhistorical project, which was to invent English-style ballads relating heroic deeds of Roman history, was directly intended to inspire young Britons to deeds of [33/34] heroism and patriotic service. Macaulay's "Horatius at the Bridge" and other poems were intended to inspire the young men of England by presenting contemporary attitudes in ancient dress, though, granted, in this case Macaulay has ample support in Livy.

Left: The Catapult. Right: Faithful unto Death. Both by Sir Edward Poynter.

The Victorian presentation of Victorian ideas and ideals in Roman dress appears particularly clearly in the art of the time. For instance, Sir Edward Poynter's The Catapult (1868; Newcastle on Tyne, Laing Art Gallery), a painting which could be expected to appeal to those brought up on Caesar, shows heroic effort in behalf of the Roman cause, and his Faithful unto Death (1865; Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery) of three years earlier provides an even more patently relevant image of an individual's sacrificing himself in the cause of duty. Poynter's image of a Roman sentry faithfully keeping his post as Vesuvius rains fiery death upon Pompeii furnished Victorian England with a powerful paradigm of proper conduct necessary for a colonial power whose soldiers and administrators often functioned against overwhelming odds.Sir John Everett Millais' The Romans Leaving Britain (1865; Manchester, City Art Gallery), which presents the parting of a Roman soldier from his British love, offers both such an image of painful acquiescence to the call of duty and an obvious representation of the relation of Rome and Britain, the nation which Victorians often believed was intended to fill the place in human history once occupied by the Italian city-state. Swinburne's sonnet "'Non Dolet'" similarly uses ancient Roman heroism but applies it to Italy of the Risorgimento. The octet relates how, when Paetus Cecina hesitated after being ordered to kill himself by the Emperor Claudius, his wife took the dagger from him, stabbed herself, and gave it to him, saying, "Paete, non dolet" (it does not hurt). The sestet applies this classical example to Italy of the Risorgimento:

It does not hurt, Italia. Thou art more

Than bride to bridegroom; how shalt thou not take

The gift love's blood has reddened for thy sake?

Was not thy lifeblood given for us before?

And if love's heartblood can avail thy need,

And thou not die, how should it hurt indeed?

Swinburne thus rings another change on the constant tendency of Western revolutionary thought to invoke instances of ancient Rome heroism for inspiration and justification. [34/35]

A far more common mid- and late-Victorian tendency was to see Rome less directly as the model for the British empire. The paintings of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Sir Edward Poynter, Sir John Everett Millais, and a host of minor imitators present the life of ancient Rome in such a manner that their images appear to contain Victorian English men and women. These painters on occasion present images of heroism or virtuous action, but they generally concern themselves more with images of daily life or merely interesting, as opposed to major, events.

Victorian fascination with the minutiae of ancient Roman life has various somewhat paradoxical implications for these culturally powerful images or paradigms. By showing the Romans at home, as opposed to the Romans in the Forum or on the battlefield, such paintings encouraged the Victorian viewer to identify with the inhabitants of a heroic age precisely by making that age less heroic. Eighteenth-century commentators on Homer often remark with surprise upon the poet's presentation of a great hero cooking a chop, but many in the Victorian audience apparently wanted precisely such a view of ancient Rome and its inhabitants. Thus, however much Carlyle urged that men and women in the age of Victoria desperately needed heroes and other models for greatness, painterly realism and the emphasis upon genre detail in Victorian pictorial representations of ancient Rome tend to produce singularly unheroic views of ancient greatness. Indeed, such homey, homely, presentation of the ancient past tends to remove much of its uniqueness at the same time that it makes it more accessible. In other words, the closer the Victorian got to ancient Rome, the more he or she encountered a mirror rather than a lamp.

Left: A Tepidarium

Right: Catallus at Lesbia's both by Sir Laurence Alma Tadema

Such a tendency for Victorian painters to find reflections of their contemporaries in the classical Roman past appears with particular clarity in the works of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, the great Victorian master of Roman subject pictures. although he occasionally depicts major events in Roman history, such as the encounter of Anthony and Cleopatra or the soldiers' selection of Claudius to succeed Caligula in A Roman Emperor (1871; Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery), he more usually paints archeologically reconstructed genre scenes peopled by anonymous inhabitants of ancient Rome. The Juggler (1870), The Discourse (1865), The Roman Dance (1866), The Armourer's Shop (1866), A Collector of Pictures (1867), [35/36] In the Temple (1871), A Visit to the Studio (1873), On the Steps of the Capitol (1882?), and The Baths of Caracalla (1899) all present such images of daily life in ancient Rome. Catallus at Lesbia's (1865) and At Lesbia's (1870) similarly employ the devices of such archeological genre painting to represent an event in ancient cultural history, and many of this extraordinarily popular artist's other pictures provide the Victorian spectator with similarly educational experiences, though a good number, such as An Apodyterium (1866) and A Tepidarium (1881; Port Sunlight, Lady Lever Art Gallery), sugar-coat (or at least embellish) an archeological reconstruction of ancient Roman daily life with a culturally sanctioned presentation of unclothed femininity.

Such curiously mixed intentions appear again when we consider how British, or at least Northern European, are Alma-Tadema's inhabitants of Rome, for as this last painting reveals with particular clarity, Alma-Tadema's Romans have a definite British cast. Black hair and dark complexions are generally replaced by more northern skin and hair color as the painter peoples his canvases with Victorians in Roman dress and self-consciously merges past and present, Rome and England, classical and modern. Alma-Tadema's An Earthly Paradise (1891), which presents a Victorian image of motherhood in Roman guise, universalizes, perhaps justifiably, Victorian attitudes, while his Amo Te, Ama Me (1881) and Vain Courtship (1900) are little more than Victorian genre scenes, such as might have been painted by Mulready, Millais, or a host of others, in Roman dress. This urge to provide images of Victorian Romans to create Roman Victorians appears throughout this artist's oeuvre. Works like The Discourse (1865) or A Collector of Pictures (1867) take the popular middle-class genre picture and skillfully place it in the ancient past, thereby endowing it with a kind of dignity and historical precedent that many Victorians, particularly those in the rising middle- and upper-middle classes, much desired. Such works suggest to the Victorian audience that things change little, that the Manchester mill owner or London shipping agent exist in a continuum of power that reaches down from the classical past and confirms both their status and heritage. For the wealthy, but relatively uneducated, members of the commercial classes who provided one of the essential bases of Victorian England's prosperity and power, these works serve as a replacement for Arnoldian culture. Emphasizing both the essential relevance of the Roman past to [36/37] nineteenth-century England and the essential equivalence of the two ages and nations, such self-congratulatory and reassuring works necessarily proceeded by emphasizing the ordinariness of ancient Rome. As Frances Spalding points out, Alma-Tadema's painting

relies on familiarity; his Roman men and women are experiencing emotions that could easily be felt by his Victorian public. Ernest Chesneau, the critic, wrote that Alma-Tadema "put the antique world into slippers and dressing gown". His Paintings are meticulously painted day-dreams, heightened by the use of trompe d'oeil illusion. The exact archeological reconstructions house not the high, tragic events of ancient history, but more intimate domestic scenes. His ladies yearn, as do Burne-Jones's maidens and Leighton's goddesses, but for more sentimental reasons; they loll on marble benches covered with furs and confide to each other their secret desires, or they lean on ramparts overlooking the Mediterranean awaiting the return of the men. [p. 64]

Spalding also suggests that Alma-Tadema's works appealed to "self-made merchants and industrialists," for they "implied classical learning on the part of the owner, who may well have lacked the classical education of the upper classes." Thus, in contrast with Romantic painting's characteristic images of crisis and even apocalypse, this strain of Victorian art offered its audience what we may term images of comfort and self-congratulation. In addition to depicting major events of Roman history and landscapes filled with Roman ruins, Romantic art frequently employs the destruction of Pompeii as a paradigm for political, personal, and metaphysical crisis. When Alma-Tadema painted a subject from Bulwer-Lytton's popular The Last Days of Pompeii (1834), he produced the tranquil Glaucus and Nydia (1867; formerly Allen Funt Collection), which completely avoids those aspects of the novel upon which other painters concentrated.

Left: A Coign of Vantage Right: Silver Favourites both by Sir Laurence Alma Tadema

One sure sign of the popularity of such Romanized images of Victorian life appears in the fact that Alma-Tadema had a host of minor imitators who continued to work in this vein until the early 1920s. In fact, Alma-Tadema seems to have created something very like a subgenre with pictures like The Question (1877), Amo Te, Ama Me (1881), Expectations (1885), and A Coign of Vantage (1895), and Silver Favourites (Fig. 6; 1903; Manchester, City Art Gallery). These works established a fashion for paintings of an attractive young woman seated or lying on a high-backed marble bench or one placed against a marble wall or parapet over which the viewer catches sight of ocean, usually far below, and an intense blue sky.

On the Terrace by Sir Edward Poynter

In its prime variant, a young woman sits or lies on Alma-Tadema's curved bench, and in both versions bits of landscape, often in the form of a single beflowered tree branch, appear. Sir Edward Poynter's On the Terrace (1889; Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery), Ernest Walbourn's Butterflies, Oliver Rhys's The Songbird, William Stephen Coleman's Playtime, William Oliver's Roses, Alexander Rosell's The Musicians (1913), and John William Godward's A Souvenir (1920) exemplify his popular pictorial theme. [37/38]

Such treatment of contemporary figures has artistic precedent, of course, but previously the figures thus Romanized had a clearly recognized historical identity and a political position, and such Romanization made politically important statements. Napoleon laid claim to an imperial heritage that stretched back to ancient times when he had himself depicted in Roman armor, and when the sculptors of young America presented Washington, Franklin, and Jefferson similarly, they also made statements in an accepted and recognized political language (Classical Spirit). These Victorian Romans or Victorianized Romans, on the other hand, are only indirectly and implicitly the carriers of a political ethos. They are merely the inhabitants of an empire rather than its military or political leaders.

Contrasting British representations of classical Rome with those produced in France, such as Jean-Léone Gérome's The Death of Caesar (1867; Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery), suggests several explanations for this tendency to domesticate ancient history as a source of comfort for contemporary English men and women. In the first place, the occurrence of repeated revolutions, coups, and changes of French government between 1780 and 1880 certainly kept the political valences of Roman imagery in the dominant position that David's Oath of the Horatii (1785; Paris, Louvre) had given it. The differences between what we may call the political economics of French and British picture-buying offer an additional, equally important, explanation for the differences between the two countries' uses of Roman subject. In France a painter who did not (or was not allowed to) exhibit at the yearly Salon could still attain financial security and reputation, because various French governments continued to support the production of history painting by purchasing such subjects for display in museums and government buildings. Such purchases therefore subsidized the production of history painting and encouraged painters to paint essentially public subjects. In contrast, with the exception of the ill-fated scheme to decorate the rebuilt Houses of Parliament, the British government provided no such patronage, and as artists and critics continually complained, neither did the Church of England. British painters therefore had to produce works that would appear in private, rather than public, settings; and very few artists were willing, like William Holman Hunt, to risk years of hard work to producing large works that would be exhibited individually at paid public exhibitions. [38/39]

Furthermore, since artists appealing to the British public appealed to members of the newly rich as well as to the aristocracy, which had earlier formed the only patronage class, they had to suit their works to settings pervaded by attitudes that were still largely those of the middle classes. In other words, no matter how sumptuous the home of the Manchester merchant, Liverpool shipping magnate, or Birmingham mill-owner, it still furnished no appropriate place for ancestral portraits or history paintings; and since most such newly successful businessmen were evangelicals, whether dissenters or members of the Church of England, religious works had little appeal for them. In this situation, paintings of Roman life that seemed to furnish stature and pedigree for those without ancient lineage had a powerful attraction.

Related to this dominant tendency of British artists and writers to accept Rome as a type of Victorian Britain is that relatively minor, if interesting, strain that looks, not at the heroism of Republican Rome or of the later Empire, but at the spiritual problems, ennui, and even despair of the Roman decadence. Starting with Swinburne, Victorian authors early began to present sympathetic depictions of those Roman pagans who resisted the coming of Christianity because it represented the new and crude, the barbarous. His "Hymn to Proserpine (After the Proclamation in Rome of the Christian Faith)" embodies the world-weariness of those who have seen their divinities replaced by new ones. The speaker admits that the gods "who give us our daily breath," the gods he worships, "are cruel as love or life, and lovely as death." Nonetheless, although he accepts that the Christian deity — whom he insists on treating in pagan fashion as a pantheon — "are merciful, clothed with pity, the young compassionate Gods," he finds Christianity and its world "barren," and he cries out:

Wilt thou yet take all, Galilean? but thou shalt not take,

The laurel, the palms and the paen, the breasts of the nymph in the brake. . . .

And all the wings of the Loves, and all the joy before death.

Despite such brave assertions, the pagan worshiper complains to Christ, "Thou hast conquered, 0 pale Galilean; the world has grown grey from thy breath." Of course, Swinburne employs such ancient Romans, much as Browning had used Cleon, an imaginary [39/40] post-classical virtuoso philosopher-poet, to embody a spiritual state corresponding to the modern loss of belief. Equally important, he establishes the essential similarity of the positions of the would-be believer in ancient Rome and Victorian England. In creating images of mankind thus cast into the sea of time that swamps all things and all beliefs, the poet promises that Christianity will find itself replaced by other faiths, just as the pagan belief of ancient Rome found itself replaced by Christianity; and he makes contemporary Victorian readers realize that they share most, not with the early Christians, their ancestors in faith, but with the pagans whose beliefs these Christians replaced. (A French pictorial analogue to Swinburne.)

Not all of Swinburne's use of Roman subject takes such an explicitly high-minded form, for like Dowson and many others of the later nineteenth century, he found that the very idea of decadence titilated and had its own appeal. Even Alma-Tadema, who generally produced genre images of middle-class appeal, found himself occasionally attracted to images of decadence. His Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), which represents the emperor aromatically smothering a favorite, provides a true visual complement to Swinburne's many images of roses, flowers, and mingled death, pain, and pleasure.

All these examples of Victorians mining the past reveal the way artists and writers of the nineteenth century drew upon the complex web of meanings present in the historical and cultural record. Not all uses of ancient Rome possessed such valences, for even artists like Alma-Tadema and Leighton, who produced between them so many ideologically filled images, occasionally used the Roman past in an almost completely neutral, unvalorized manner, one reminiscent of the aesthetes and decadents, one that delights in the past for its color and form and avoids any meaning it might contain as having lesser artistic importance. Frederic Leighton's The Knucklebone Player thus offers us little more than a typical Victorian "fancy picture," which chooses to show its beautiful woman, not in contemporary dress, but as an inhabitant of Rome or its dominions. Similarly, Alma-Tadema's Young Woman in a Garden (1866) presents a typical Victorian fancy picture, and, like Alma-Tadema's works of archeological genre, these prompted a host of imitations well into the twentieth century. What we have here is a Roman subject used only as an occasion for its opulent [40/41] color as an excuse or stimulus for an aesthetic experience.

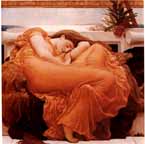

Flaming June by Frederic Lord Leighton (1895; Puerto Rico, Museo de Arte de Ponce)

Much the same approach to the Roman past appears, I think, in Leighton's Flaming June, whose flattened, curvilinear forms comment implicitly on Victorian attempts to mine the past for meanings and messages applicable to the present. Just as the Victorians, like all others aware of a cultural tradition, find it impossible to avoid encountering both themselves and messages intended for themselves in the past, they also reveal that at some time the very discoverers and conveyers of these mirror images and messages find the images themselves of chief value. They resist meaning, they resist interpreting, and they encounter, instead, a beauty of form and color. The degree to which such essentially aesthetic treatments of Roman subjects resist meaning perhaps best appears in the obvious fact that one cannot even be certain that a work like Flaming June depicts a Roman subject at all, for with equal accuracy it could be said to represent a Grecian one or one based upon a purely imaginary, quasi-classical world. Such turning away from meanings, discovered, created, or found, cannot attract for long, but they cannot be ignored for long either, and much of the richness and complexity of the Victorian age appears in the way the same artists pursue contradictory attractions of ancient Rome.

Related Materials

Bibliography

Baron, Hans. The Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

Brooke, Anthea. Victorian Painting. Catalogue for exhibition November-December 1972. London: Fine Art Society, 1972.

The Classical Spirit in American Portraiture. Exhibition Catalogue, Providence: Brown University, 1976.

Girouard, Mark. The Return to Camelot: Chivalry and the English Gentleman. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981

Jenkyns, Richard. The Victorians and Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Spalding, Francis. Magnificent Dreams: Burne-Jones and the Late Victorians. Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1978.

Turner, Frank M. The Greek Heritage in Victorian Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981.

Wolff, Robert Lee. Gains and Losses: Novels of Faith and Doubt in Victorian England. New York: Garland, 1972.

Wood, Christopher. Olympian Dreamers: Victorian Classical Painters. London: Constable, 1983.

Created 20 May 2007

Last modified 5 November 2021