‘the Teacher and exemplar of his age’ — Thomas Carlyle, ‘Goethe,’ p. 208

nce I could speak joyfully about beautiful things, thinking to be understood; — now I cannot any more; for it seems to me that no one regards them’ (7.422). This confession in the closing pages of Modern Painters 3 shows the deep change of mood that had come over Ruskin by 1860; the reason he gives for this change shows that his work was already taking a new direction. The love of nature in Modern Painters 1 has been replaced by a concern for men; optimism has given way to a darker mood, sometimes of depression and sometimes of anger. The outcome of this sea-change was the expansion of his art criticism into an attempt to account for the whole of man’s activity.

There were good reasons for Ruskin to be both depressed and angry. He had undergone great changes between 1843 and 1860; difficulties in his emotional life exacerbated the crises of intellectual thought, and the changes in his critical attitude in turn produced problems in his private relationships, particularly with his parents. The most important changes were in his feelings for nature and in his belief in God. As we saw in Chapter 1, these were mutually supporting ideas, and a change of attitude towards one inevitably placed the other in a different light. Ruskin’s doubts in both areas started at the same time. After the heavy theoretical work of Modern Painters 1 and 2 he suffered a severe reaction, which led to depression and an apparently psychosomatic illness; the emotional and intellectual difficulties of the next decade can be traced back to this near nervous breakdown. The books had given an entrée into fashionable literary society, which must have delighted his ambitious parents, but it soon became clear that a life of breakfasts and balls was not to his taste. Alarmed by his melancholy state, his parents encouraged him to think of marriage. This in turn produced a new difficulty, the disastrous relationship with Effie Gray.

This is not a biography, and I must be brief.1 Euphemia Gray was the daughter of a family friend; when she was still a young girl Ruskin had written the fairy tale The King of the Golden River to entertain her. [119/120] (Curiously, the destructive gold and the fruitful paradisical valley which appear in this story also make their way into the later writings on economics.) Ruskin courted Effie with love letters no more and no less passionate than those of other men, and in the spring of 1848 they were married. Something however went wrong: Ruskin never made love to his wife. Either he was completely impotent or there was some physical or emotional difficulty between them that prevented the marriage being consummated. He later denied that he was impotent, and said that there had been something wrong with Effie, so that the moment had been postponed. Eventually it became too late.

In an age that was reticent about sex, the stresses between John and Effie did not at first appear. In 1848, prevented by the political situation on the Continent from going to Italy, they travelled in Normandy. Effie played her part well, but conflict was inevitable between her and Mrs. Ruskin over their mutual property, John. Complaints about Effie’s attitude and domestic incompetence multiplied, even though John took her away from his parents to Venice in 1849-50 and 1851-52. For her part, Effie had good cause to protest, and reacted by having some form of emotional illness herself. Ruskin was really quite well during the first four years of marriage, perhaps because parental pressure was greater on Effie. Their life in Venice was a civilized solution to their private failure. The city was occupied by the Austrians; and while he had his work all around him, she had a squadron of Austrian officers to escort her to the garrison balls and galas. However, it was clear by the end of 1851 that there was little except the conventions of society keeping them together. Ruskin told his (admittedly hostile) parents that ‘the only way is to let her do as she likes — so long as she does not interfere with me: and that, she has long ago learned — won’t do’ (LV110).

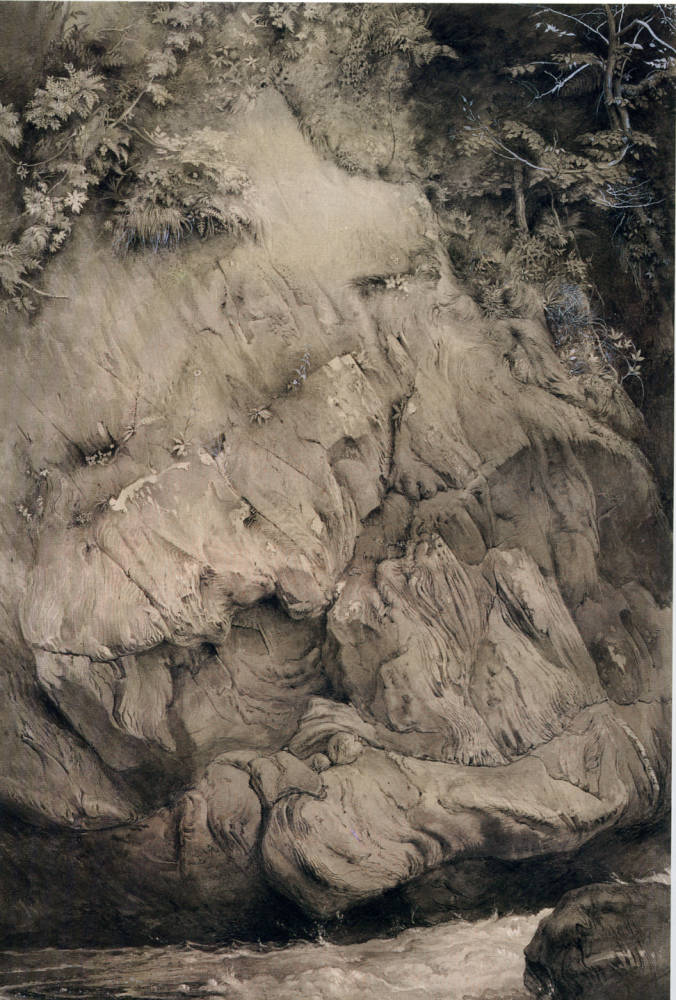

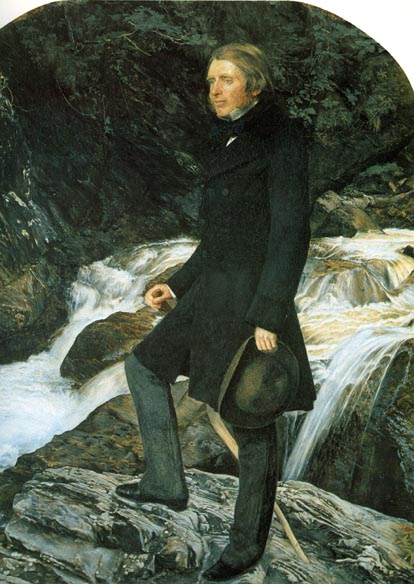

Since divorce did not effectively exist, there was little that could be done. The crisis came in 1853. Asked to lecture at Edinburgh (these were to be his first public lectures, and his parents were very worried by the idea), Ruskin decided to prepare his text and take a holiday in Scotland at the same time. Thanks to his association with the Pre-Raphaelites, he had become friendly with John Everett Millais, and Millais and his brother William were invited to come too. Ruskin was doubtless keen to work closely with one of the new school whose cause he had championed. Accommodation was found at Brig o’Turk, in Perthshire, and the holiday became something of a rustic house party. It was not quite the fête champêtre intended, for it rained a great deal. The rain and other difficulties meant that the portrait Millais was painting [120/121] of Ruskin (ill. 31) had to be finished in London. Ruskin made a study of the rocky bank that forms a background of the picture (ill. 32); the crisp delineation suggests that he was learning from Millais as much as Millais was learning from him.2 Millais and Effie were thrown into each other’s company. In April 1854 she found an excuse to leave London and return to her father’s house in Perth. From there she returned her wedding-ring to the Ruskins.

Left: Gneiss Rock, Glenfinlas. John Ruskin. 1853. Stimulated by Millais, Ruskin concentrates his geological knowledge into a powerful example of the first order of truth.

Right: J. E. Millais, John Ruskin, 1854. Ruskin at thirty-five, begun at Glenfinlas in 1853 and finished in strained circumstances in London in 1854, after Effie had left Ruskin and their marriage had been annulled. The left-hand rock on the far side of the stream is the subject of Ruskin's drawing. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The scandal was splendid, for those not directly involved; Millais said at the time that the two main topics of conversation in society were the Crimean War and Ruskin’s marriage (D. Leon, Ruskin, the Great Victorian, 196). Divorce was possible only by means of an individual act of Parliament or through the Church Courts; Ruskin chose not to defend the action brought against him,4 and suffered the public humiliation of having the marriage annulled by the Church on the grounds of his ‘incurable impotence’ (Leon 198). Effie married Millais in June 1855. This time the marriage was a success, but this did not prevent Effie from ensuring, when the time came in 1870, that Ruskin’s last chance of happiness would be destroyed.

The private misery of unhappy marriage and the public embarrassment of its annulment must have been bitterly painful, but much more agonizing — and far more significant for him in the long run — was the change in Ruskin’s attitude to the original twin sources of his inspiration, nature and God. Simultaneously the certainties that had sustained him began to weaken. This was the origin of the crisis that had produced the breakdown in 1847 which his marriage had at least partly been intended to cure. Modern Painters 1 and 2 are the monument to an upbringing in natural theology and Evangelical determinism, but almost immediately afterwards a reaction set in: ‘All that I had been taught had to be questioned; all that I had trusted, proved’ (35.431). His was by no means an isolated case, for many contemporaries were suffering religious doubts that left them bereft of inspiration — and therefore harsher in their intellectual conviction of the need for moral law. The discoveries of the geologists and the arguments of the Biblical critics were gradually eroding the authority of the Bible as the word of God. For Christians like the Evangelicals, whose beliefs were built on this authority, the destruction of the Bible as the indisputable word of God meant the destruction of all faith. The arguments and trials in the 1860s surrounding the publication of Essays and Reviews and of Bishop Colenso’s The Pentateuch and the Book of Joshua critically examined were to reflect the religious crisis of the time.6 Ruskin had already undergone his test of faith by then, but although he repudiated his earlier Evan-[121/122]gelical outlook, he did not immediately publicize his agnosticism.7 Throughout the 1850s the struggle remained a private one.

The first difficulty was that he could not deny the evidence of his own eyes. At Oxford he seems to have accepted Buckland’s natural theology, but Buckland’s accommodations with the Bible story could not survive the discoveries of more advanced geologists like Charles Lyell, who regarded the mixing of theological and geological questions as merely a hindrance to both (Lyell, Principles of Geology, vol. 1, 58). It was of Lyell’s work that Ruskin was thinking when he made the often quoted comment in 1851: ‘If only the Geologists would let me alone, I could do very well, but those dreadful Hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses’ (36.115). It was the Evangelical crux: either the Bible was completely true, or it was completely untrue; either the world was made in six days, or it was not made by God at all; either the prophecies would be fulfilled, or Christ’s teaching was nonsense and the world was empty of meaning. In spite of determined efforts to cling to the earlier certainties, the hold on belief gradually weakened.

Ruskin soon conceded that the Bible might be just ‘another history,’ but there remained the hope that the difficulties of rational belief might be met by an act of faith. In 1848 he was prepared to accept, privately, Pascal’s view that since logically it was as impossible to disprove the existence of God as it was to prove it, it was best to wager on there being a God after all. But it was only a temporary answer. During Easter 1852 he passed through his own week of doubt, pain and eventual resolution. It is significant that he had recently written a private commentary on the Book of Job, for Job was the Old Testament prophet who finally found wisdom only after a thunderous reminder from God that He was the creator of the world.9 On Good Friday Ruskin confessed in a letter to his father that he had been ‘on the very edge of total infidelity — and utterly incapable of writing in the religious temper in which I used to do’ (LV244). To secure himself, he fell back on Evangelical discipline: ‘I resolved that at any rate I would act as if the Bible were true’ (LV244) — and this brought consolation. But he knew how far he had already gone. In brighter mood on Easter Sunday, he explained that, when he had written earlier that he had come to the place where ‘the two ways met,’

I did not mean the difference between religion and no religion; but between Christianity and philosophy: I should never, I trust, have become utterly reckless or immoral, but I might very possibly have become what most of the scientific men of the present day are: They all of them, who are sensible — [122/123] believe in God — in a God, that is: and have I believe most of them very honourable notions of their duty to God and to man: But not finding the Bible arranged in a scientific manner, or capable of being tried by scientific tests, they give that up — and are fortified in their infidelity by the weaknesses and hypocrisies of so called religious men. . . . The higher class of thinkers, therefore, for the most part have given up the peculiarly Christian doctrines, and indeed nearly all thought of a future life. They philosophize upon this life, reason about death till they look upon it as no evil: and set themselves actively to improve this world and do as much good in it as they can. [LV246-47]

Effectively, this was to be his own future position.

The mention of death betrays Ruskin’s real worry, for he was struggling with an apparently insoluble doctrinal problem. The Evangelical was taught to fear death, because all but a few were condemned to damnation; but the promise of damnation was also the promise of an after-life for those who were saved. If therefore he rejected Evangelicalism he might not have to fear future damnation, but in doing so he also rejected the possibility of an after-life — and the fear of death remained. The theme of death had been drummed into him ever since he was a child, death irrevocably associated with evil by St. Paul: ‘sin entered into the world, and death by sin.’ During his heart-searching in Venice in 1852 he recalled what a shock it had been the first time he had seen a man on his deathbed (LV170). When Evangelicalism was eventually sloughed off, he was in many ways in no more secure a position, for all that life now held was eventual negation by death, and only grim determination and attention to duty could stave off a sense of futility. ‘It is so new to me,’ he told Carlyle, ‘to do everything expecting only Death’ (36.382). It is not surprising, then, that so many of Ruskin’s arguments should be expressed in terms of the opposing images of life and death, or that man’s conduct should be presented as a choice between them.

Detail from Paolo Veronese's Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Ruskin's study of the painting in 18578 led to an “unconversion” away from narrow religious scruples and into full acceptance of sensual art: “working from the beautiful maid of honour . . . I was stunned by the Gorgeousness of life” (7.xli). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The certainty of death can also produce its opposite, the affirmation of life, and it was the positive values of life, and especially art, which finally gave release. The moment came in 1858, and once again it was an experience closely associated with a picture. That summer he had gone to northern Italy, still making geological notes for Modern Painters, but the mountains palled, and he went to Turin to study in the Gallery of the Royal Palace. His attention was caught by Veronese’s Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Until then he had considered Veronese to be one of the ‘sensualists,’ lost in the fall of Venice, but working on a [123/124] careful copy of the painting he gradually changed his view: ‘One day when I was working from the beautiful maid of honour in Veronese’s picture, I was struck by the Gorgeousness of life which the world seems to be constituted to develop, when it is made the best of’ (7.xli).10 He had reached another turning-point, and this moment of perception became, as time distanced him from it, one of the most significant in his life. Acceptance of the positive values of existence, this ‘Gorgeousness’ meant escape from a negative religion.

I was still in the bonds of my old Evangelical faith; and, in 1858, it was with me, Protestantism or nothing: the crisis of the whole turn of my thoughts being one Sunday morning, at Turin, when, from before Paul Veronese’s Queen of Sheba, and under quite overwhelmed sense of his God-given power, I went away to a Waldensian chapel, where a little squeaking idiot was preaching to an audience of seventeen old women and three louts, that they were the only children of God in Turin; and that all the people in Turin outside the chapel, and all the people in the world out of sight of Monte Viso, would be damned. I came out of that chapel, in sum of twenty years of thought, a conclusively un-converted man. [29.89]

So wrote Ruskin in Fors Clavigera in 1877; but, as we have seen before in accounts of the key moments of his life, there are other versions of the same story. As George Landow has pointed out (281-84), when the moment is described in Praeterita in 1888 the crucial moment is no longer located in the plain Protestant chapel, but afterwards, before Veronese’s picture:

I walked back into the condemned city, and up into the gallery where Paul Veronese’s Solomon and the Queen of Sheba glowed in full afternoon light. The gallery windows being open, there came in with the warm air, floating swells and falls of military music, from the courtyard before the palace, which seemed to me more devotional, in their perfect art, tune, and discipline, than anything I remembered of evangelical hymns. And as the perfect colour and sound gradually asserted their power on me, they seemed finally to fasten me in the old article of Jewish faith, that things done delightfully and rightly were always done by the help and in the Spirit of God. [33.495-96]

This later version emphasizes the positive value of the experience rather than the loss of religious faith it involved; it also stresses the power of visual sensation over him. In this case it is almost a synaesthetic moment, for the music (which he also mentioned to his father at the time in very similar terms) seems as important as the picture. At last, Ruskin had learned that he could accept the sensuality of art and man. He wrote to his friend Charles Eliot Norton, with whom he could [124/125] speak frankly: ‘I’ve found out a good deal — more than I can put in a letter — in that six weeks, the main thing in the way of discovery being that, positively, to be a first-rate painter — you mustn’t be pious; but rather a little wicked, and entirely a man of the world. I had been inclining to this opinion for some years; but I clinched it at Turin’ (LN1.67).

An altered view of the artist has important implications for the relationship between the artist and society, but this new view also has a lot to do with Ruskin’s loss of ‘landscape feeling.’ The love of God and the love of nature were so nearly the same thing that it has been a little artificial to discuss them separately. He recognized their interconnection in the Good Friday letter of 1852, confessing nearness to ‘total infidelity . . . and exactly in the degree in which this infidelity increased upon me, came a diminution of my enjoyment of even what I most admired more especially of natural things’ (LV244). The crisis of faith and the loss of landscape feeling played their part in the illness of 1847; indeed the loss of religious inspiration may partly have been the result of the failure by the external world to produce any longer the emotions which confirmed the presence of God.

In an excellent analysis of this change of heart, Francis Townsend concludes that by 1849 ‘Ruskin’s landscape feeling was dead’ (49). True, the zest for nature in itself disappears, but it is rather its context which changes. He could no longer feel totally annihilated by the power of God and nature, as he had in 1842, beside the fountain of the Brevent, but landscape retains its value so long as it is associated with man. The shift can be seen by comparing that earlier description quoted on page 31 with a passage in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849). Whereas before ‘to become nothing might be to become more than Man’ (4.364), he now records the change in his feelings when the scene was mentally transposed to an uninhabited part of the world: ‘The flowers in an instant lost their light, the river its music; the hills became oppressively desolate; a heaviness in the boughs of the darkened forest showed how much of their former power had been dependent upon a life which was not theirs.’ That life was not the presence of an unseen Deity, but ‘human endurance, valour, and virtue’ (8.223-24).

The result of the gradual loss of landscape feeling was a shift to a concern for a man-centred art. Modern Painters 3 (1856) shows how his responses were changing. In the first two volumes the value of nature is unquestioned, but in the third he dares to ask if the pleasure taken in landscape really is such a good thing. An answer is sought in the history of man’s attitude to nature, culminating in the chapter ‘The Moral of [125/126] Landscape.’ The conclusion is that nature does have value, but, as we saw in Chapter 1, the purely poetic response is secondary to other, higher needs. While a passion for nature always works to the good, it is also a sign of weakness, in that it is insufficient simply to worship nature on its own; one must act positively to bring about moral improvement as well. By calling for a ‘science of aspects’ which involved a harder look at man and his surroundings than the reveries of the poet, he was signalling the change of intellectual position necessary now that his emotional responses were no longer able to sustain his earlier Romantic outlook. ‘The Moral of Landscape’ represents the half-way stage to a social view of art — which is why its argument is so tortuous. The problem was to decide how far nature could be said to have any independent influence on man. The linked Chapters, ‘The Mountain Gloom’ and ‘The Mountain Glory,’ in Modern Painters 4 (1856) are his answer.

Typically, these two chapters are set up like an experiment, a subject for visual observation. The location is the mountain district of the Valais in Switzerland, and its character and appearance is carefully and lovingly described. It is a beautiful passage — which only serves to point the contrast that he wishes to make. It may seem to the visitor that in this region,

if there be sometimes hardship, there must be at least innocence and peace, and fellowship of the human soul with nature. It is not so. The wild goats that leap along those rocks have as much passion of joy in all that fair work of God as the men that toil among them. Perhaps more. [6.388]

Theoretically, the Valais constitutes the best possible environment man could have for the development of his moral and creative faculties — but the experiment shows that the opposite is true. He continues:

Enter the street of one of those villages, and you will find it foul with that gloomy foulness that is suffered only by torpor, or by anguish of soul. Here, it is torpor — not absolute suffering — not starvation or disease, but darkness of calm enduring; the spring known only as the time of the scythe, and the autumn as the time of the sickle, and the sun only as a warmth, the wind as a chill, and the mountains as a danger. They do not understand so much as the name of beauty, or of knowledge. [6.388]

Following this preliminary — but none the less devastating — conclusion, Ruskin suggests some possible reasons why the mountains should produce such gloom among their inhabitants. Significantly, there begins a long meditation on the obsession with death in the region, although he finds the fascination with death that turns white-painted mountain [126/127] chapels into charnel houses is the same obsession that makes an opera like Death and the Cobbler a success in sea-level Venice. The mountains are no longer praised, but blamed, for he admits that they can sometimes be ugly, and that the harsh physical conditions of mountain life cramp and brutalize the mountaineer’s existence. To grim surroundings and an unhealthy climate are added the social and cultural influences of Roman Catholicism, with its bad art, obsession with pain and encouragement of idleness and superstition (all, one must add, very Evangelical Protestant objections). The town of Sion (whose very name the Bible scholar Ruskin could not fail to read as ‘high place’) is treated as an exemplar of all the ignorance, disease and decay which is possible in mountain country. The description of Sion marks the end of Ruskin’s optimism born of natural theology; at last he admits that nature, which he has formerly read only as evidence of the benevolence of God, also warns of his anger: ‘It seems one of the most cunning and frequent of self-deceptions to turn the heart away from this warning, and refuse to acknowledge anything in the fair scenes of the natural creation but beneficence’ (6.414). He now realizes that his own responsibilities have been avoided for too long by just such a self-deception.

And yet the mountains are not wholly at fault, as the corresponding chapter ‘The Mountain Glory’ is intended to show. The mood is deliberately changed to celebrate the mountains which ‘seem to have been built for the human race, as at once their schools and cathedrals’ (6.425). Whatever their occasional ugliness, ‘the granite sculpture and floral painting’ (6.426) of the hills do have a helpful influence on mankind; their beauty plays its part in man’s ideas of art and religion. But given its beneficial effect, nature alone cannot save mankind; it can only be effective when man is reformed from within. The people of Sion might yet become happy and virtuous, but certainly not by acquiring the benefits of nineteenth-century society; the one advantage of mountain environment is its isolation from the follies and vanities of the plain.

By 1860, then, Ruskin’s attitude to both God and nature had changed; but they remained constant themes. The authority of the Bible as an Evangelical text had been destroyed; but the effect was only to widen its applicability as part of the ‘Sacred classic literature’ (33.119). The language of the Bible was no longer the exclusive property of one sect; it was not written ‘for one nation or one time only, but for all nations and languages, for all places and all centuries’ (16.399). Most importantly, the theory of typical beauty evolved from Evangelical typology [127/128] was strengthened, not abandoned, for it now expanded into a theory of universal symbolism. Nature remained the repository of those types, and God their creator, but a God that worked through man. The process of Ruskin’s mind was always towards greater inclusion, to perceive common factors in a greater number of things, to reconcile opposites and extend categories; so that the loss of a restrictive Evangelical faith opened up new areas of thought. Nor did the loss of faith lead to atheism; if it had, then it was a complete hypocrite who wrote the final peroration to Modern Painters.

If the proper subject of art is now man, then it takes on a social, rather than a personal, religious significance. The link between Ruskin’s aesthetic and social theory was architecture. He started to make notes on architecture on a large scale almost immediately after completing Modern Painters 2 in 1846, and for the next decade the subject occupied most of his attention. There are several reasons for this temporary abandonment of the defence of Turner: quite simply there was the desire for a change after the second volume of Modern Painters; and, further, he could see that his arguments had raised questions which required fresh thought before they could be resolved in the next volume, with its half-apologetic subtitle, ‘Of Many Things.’ A forceful reason for calling attention to the beauty of medieval buildings, as he pointed out in the preface to The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), was that so many were being destroyed ‘by the Restorer, or Revolutionist’ (8.3n). It is also true that a weakening response to nature made a change of subject matter necessary, although his first notes on architecture had been intended for the continuation of Modern Painters, and later, when he fully developed the concept of the close links between architecture and nature, the subject grew back towards the original theme. ‘The last part of this book, therefore,’ he wrote of The Stones of Venice in 1852, ‘will be an introduction to the last of Modern Painters’ (10.208n). He did not know that there were three more volumes to be written before the defence of Turner was ended.

Two external factors also turned Ruskin’s thoughts to architecture, and consequently to social questions. Firstly, there was the desire to make a contribution to the controversy surrounding the Gothic Revival. Although the Gothic style was generally accepted as suitable for ecclesiastical building, the driving force for the revival had come from Roman Catholics, or near-Catholics, and thus the purely architectural problem was mixed with a doctrinal one which made it difficult for the true Protestant — such as Ruskin was supposed to be — to fully accept the style. The leading English exponent of the Revival was Augustus [128/129] Welby Pugin, who was received into the Catholic Church in 1836, the year of the publication of the first edition of his famous book Contrasts.

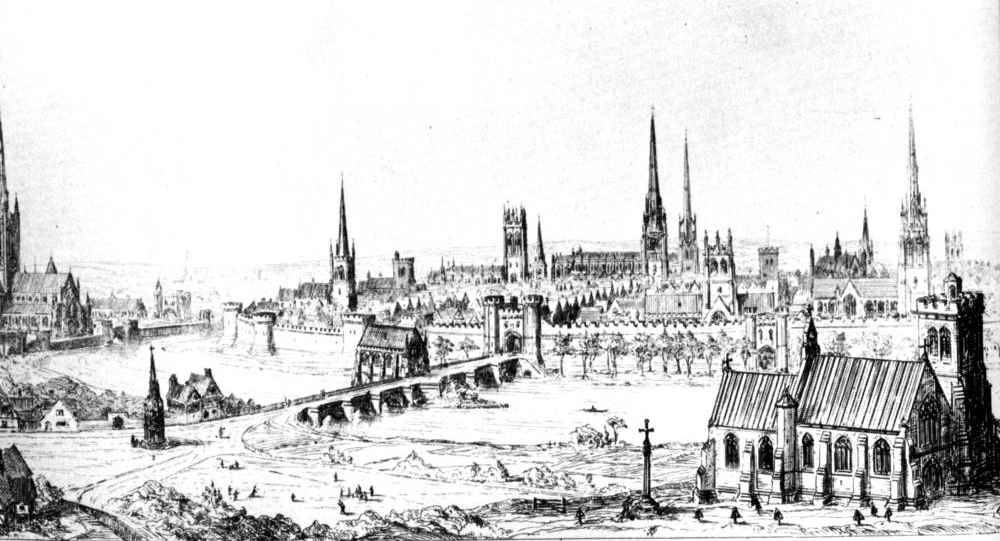

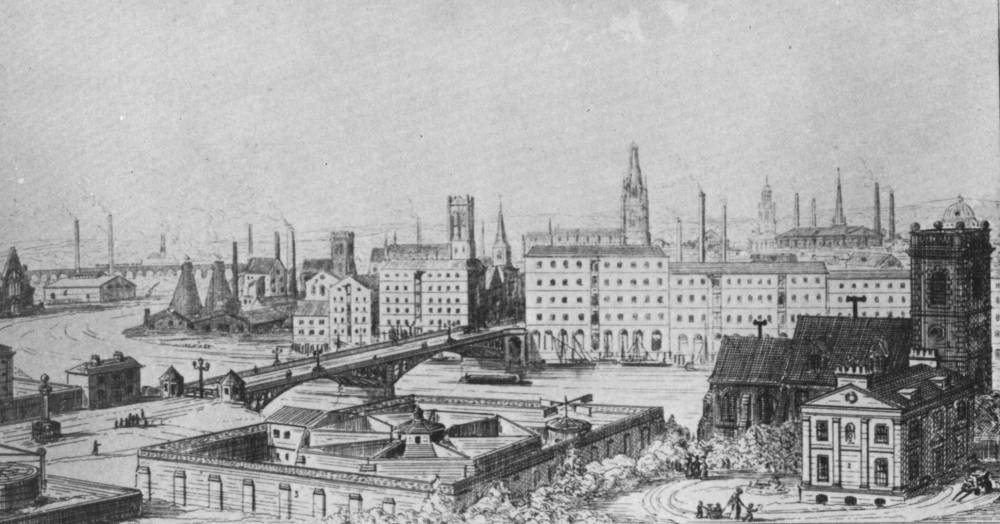

Illustration to “Contrasts”. Medieval Catholic Christian [top drawing] versus nineteenth-century Protestant Utilitarian [below]. Sectarian chapels replace Gothic churches, and an ironworks is built over the ruins of an abbey. Though he rejected Pugin's Roman Catholic slant, Ruskin nonetheless drew the same conclusions about the relationship between the state of architecture and the condition of society.”

Ruskin was disparaging of Pugin, and claimed that he had only glanced once at his book, but this very disparagement betrays the sympathy he felt for Pugin’s view of the moral responsibilities of the architect. More especially, they had a similar view of the Renaissance. The Catholic writer Rio had opened Ruskin’s eyes to early Italian painting; and Pugin followed Rio in treating the Renaissance as the expression of the corruption that had overtaken society and the Church. Where Ruskin differed from Pugin, of course, was over Catholicism, and he derided the way people could be ‘lured into the Romanist Church by the glitter of it’ (9.437). In order to remain free of the taint of Romanism he attacked Pugin unfairly; but he was very close to him. His condemnation of sham, the view of architecture as social history, and the hope for a universal style of building, are all anticipated by Pugin. Ruskin may even have taken over from Pugin the idea of ‘contrasts’: Pugin’s illustration of the difference between a medieval and a modern English town (ill. 33) has its echo in Ruskin’s comparison of the Grand Canal in the fourteenth century and Gower Street in the nineteenth (11.4), or Rochdale versus Pisa (16.338-40).13

To the doctrinal concern to save the Gothic style for Protestantism was added the genuine fear that the social upheavals of Europe might destroy all Gothic buildings, Catholic and Protestant alike. The revolutions of 1848 affected Ruskin directly;14 they prevented him from going to Italy that year, while the journey to Normandy that was made instead helped to stimulate his interest in architecture. In October he visited Paris and Rouen, and observations there appear in The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Clearly there is sympathy for those who were suffering: ‘I am not blind to the distress among their operatives; nor do I deny the nearer and visibly active causes of the movement: the recklessness of villainy in the leaders of revolt, the absence of common moral principle in the upper classes, and of common courage and honesty in the heads of governments’ (8.261). But he was no supporter of revolution. The solution he offered — in a chapter entitled ‘The Lamp of Obedience’ — was a moral regeneration through work, specifically through building, which would release the creative potential of all engaged upon it, and end the mental and spiritual idleness which he blamed as the main cause of unrest.

The revolutions of 1848 certainly brought a sharpened political awareness, but Ruskin’s reaction was conservative. When the political disturbances in France continued to threaten his travel plans in 1851 [129/130] and 1852 he applauded Napoleon III’s coup d’Etat and the arrests that followed. Although the implications of the social theories that he himself later evolved were extremely subversive of the established order, he maintained the claim, as he put it humorously in the opening words of Praeterita: ‘I am, and my father was before me, a violent Tory of the old school’ (35.13). (This fell short of approving of the Austrian occupation of Venice, however.) His view of practical politics in the 1850s is probably best summed up by a remark in a letter: ‘Effie says, with some justice — that I am a great conservative in France, because there everybody is radical — and a great radical in Austria, because there everybody is conservative’ (LV60). In 1871 he referred to himself as a ‘Communist . . . reddest also of the red’ and as a ‘violent Tory’ four months later (27.116, 167). To the end of his life he never bothered to vote.

In spite of Ruskin’s contempt for practical politics, on the theoretical level, architecture was treated from the start as a ‘distinctly political art’ (8.20). Architecture conveys

more than any other subject of art, the work of man, and the expression of the average power of man. A picture or poem is often little more than a feeble utterance of man’s admiration of something out of himself; but architecture approaches more to a creation of his own, born of his necessities and expressive of his nature. It is also, in some sort, the work of the whole race. [10.213]

This does not however demean the other arts, for precisely what is most expressive about a building is its decoration, by painting and sculpture. This is no contradiction, for the individual work is a coherent part of a greater whole, and as such all art, but particularly architecture, expresses social history.

The idea of art as social history does not involve any loss of continuity with the idea of art as a mediator between man and nature. The social history of man can be judged in terms of how well or how badly societies have utilized, through their art, the creative energies available in the natural world. Ruskin’s choice of analogies shows the interdependence he perceived between architecture and nature — for they come from the natural sciences, crystallography, geology, zoology, anatomy (see 8.254, 9.271, 9.128). Correspondingly, the imagery of architecture was applied to natural science. The three geological eras of the earth, creation, sculpture, and decay, parallel the phases of Venetian history. In turn, the decoration of Venice is subject to the cycle of the seasons: ‘Autumn came — the leaves were shed, — and the eye was directed to the extremi-[130/131]ties of the delicate branches. The Renaissance frosts came, and all perished!’ (11.22.).

The link between nature and building, ‘this look of mountain brotherhood between the cathedral and the Alp’ (10.188), is a recurring idea, from the early essays The Poetry of Architecture onwards; it was the one aspect of the picturesque that was not rejected. Since the natural world is the source of our conception of beauty, it follows that the man-made forms which come closest to those of nature will be the most satisfying. Not that it is simply a question of isolating and imitating a particular natural form; that would be an external process. Rather, all design, in architecture, sculpture, painting, or botany, depends on the law of organic form. The dogtooth decoration does not imitate the pyramidic crystal; both are governed by the same inner force. And when architectural decoration begins to pretend that it is no longer subject to the laws of physics — in Ruskin’s terms, when it begins to pretend to be what it is not, and loses its truth — then it begins to die. A causal connection becomes apparent between the decline of architecture and the rise of landscape painting. Since buildings no longer acted as a link between man and the creative energies of nature, satisfaction had to be sought elsewhere:

For as long as the Gothic and other fine architectures existed, the love of Nature, which was an essential and peculiar feature of Christianity, found expression and food enough in them . . . but when the Heathen architecture [that is, Palladian] came back, this love of nature, still happily existing in some minds, could find no more food there — it turned to landscape painting and has worked gradually up into Turner. [LV192]

So the digression into architecture was indeed the preliminary to the rest of Modern Painters.

Having established the link between nature and the social art of architecture, Ruskin was led on to apply the law of organic form to society itself. Nature was the model for man-made form, so the organization of natural forms might become a paradigm for society. In the natural world the separate parts united in a single energetic whole, exemplifying the type of Divine purity; similarly the associative imagination of the artist combined the imperfect elements of a painting into the one possible perfect composition. The analogy between nature, art and society was there to be drawn: ‘Government and co-operation are in all things and eternally the laws of life. Anarchy and competition, eternally, and in all things, the laws of death’ (7.207). Ruskin made this [131/132] statement twice, first in his analysis of the rules of composition; later, when he turned to political economy, he saw no reason to alter a word.

The obligation upon art to improve society was a commonplace of nineteenth-century thought — it is only because artists made an attempt at the end of the nineteenth century to free art from this obligation that we now need reminding of it. Where Ruskin differed was in his reversal of the proposition. At first he accepted the standard view that art should act as a source of moral regeneration in society, but during the 1850s we are able to see a gradual shift of emphasis. While still believing that art could restore the broken links between man and nature, he came to see that art was an expression of society, an index of its health, not a cure for its corruption. The connection between aesthetic and social theories was implicit when he began the study of architecture; the change from art to sociology, if not to economics, takes place within the three volumes of The Stones of Venice.

The first volume, like The Seven Lamps of Architecture, is primarily concerned with aesthetic problems, and intended to establish certain principles of form and decoration that would produce a practical living architecture. However, during the research for the second volume, he began to see the far wider implications of the argument. Writing to John James in 1852 he seems aware of a distinction in subject matter between what had gone before and what was to follow. The Seven Lamps of Architecture and the first volume of The Stones of Venice ‘have been merely bye play — this Stones of Venice being a much more serious [volume] than I anticipated’ (LV181).

The seriousness was the result of facing the sociological question posed by the stirring opening lines of the whole work:

Since first the dominion of men was asserted over the ocean, three thrones, of mark beyond all others, have been set upon its sands: the thrones of Tyre, Venice, and England. Of the First of these great powers only the memory remains; of the Second, the ruin; the Third, which inherits their greatness, if it forget their example, may be led through prouder eminence to less pitied destruction. [9.17]

The problem — the experiment — Ruskin set himself was this. Architecture was the work of the whole nation, Venice had had fine architecture, and yet Venice fell. The conclusion must be that art, like nature, was incapable of saving mankind.

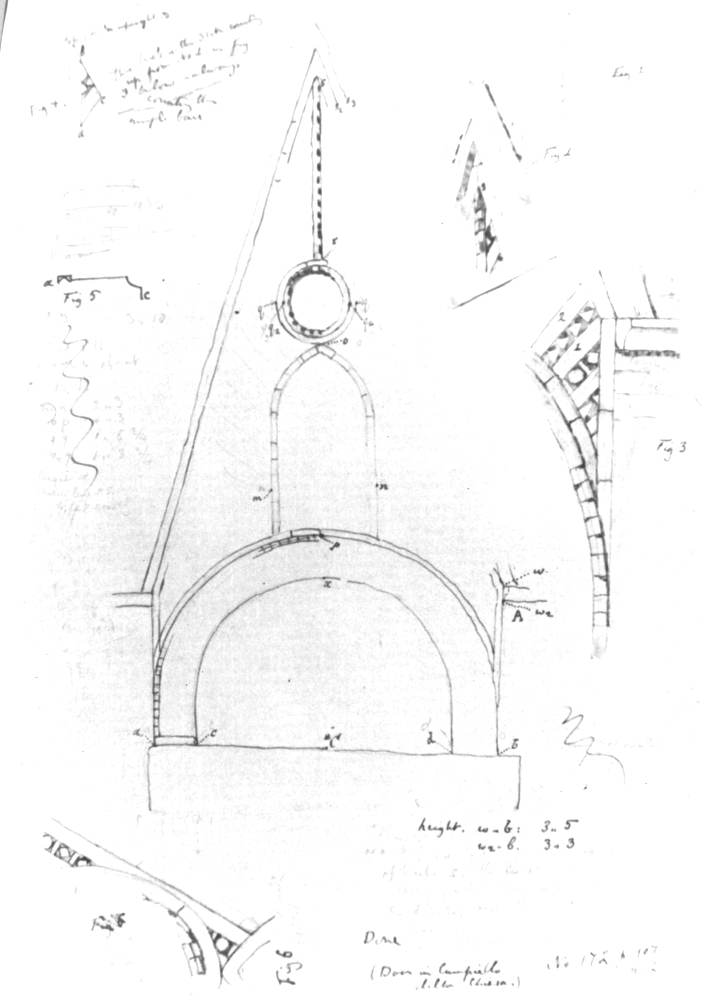

Working Study of a Doorhead in the Campiello della Chiesa, San Luca, Venice. 1849 or 1850. The measurements and calculations show the care with which Ruskin studied his material at first hand. A finished version of this subject appears as Plate 23 of Examples of the Architecture of Venice, of l851 (11.344-5). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The proposition is demonstrated in the second volume, in the key chapter on the cathedral of St. Mark’s. It begins with a series of contrasts, [132/133] first between the cathedral close of an English city and the approach to St. Mark’s through the alleys of Venice; then between the noise and glare of the piazza and the beauty of St. Mark’s itself. Some of Ruskin’s finest prose is used to show that St. Mark’s is a jewel, the greatest art the city possesses, a precious Bible in stone, but what effect does it have on the people who crowd round it?

You may walk from sunrise to sunset, to and fro, before the gateway of St. Mark’s, and you will not see an eye lifted to it, nor a countenance brightened by it. Priest and layman, soldier and civilian, rich and poor, pass it by alike regardlessly. Up to the very recesses of the porches, the meanest tradesmen of the city push their counters: nay, the foundations of its pillars are themselves the seats — not ‘of them that sell doves’ for sacrifice, but of the vendors of toys and caricatures. [10.84]

Even within the cathedral itself, in the cool and the dark, with the sound of the Austrian band in the square shut out at last, the splendour and significance of the images which decorate its wall are unregarded.

The beauty which it possesses is unfelt, the language it uses is forgotten; and in the midst of the city to whose service it has so long been consecrated, and still filled by crowds of the descendants of those to whom it owes its magnificence, it stands, in reality, more desolate than the ruins through which the sheep-walk passes unbroken in our English valleys. [10.92]

There is a parallel between the conclusion to the description of St. Mark’s and the passage on the town of Sion.16 Sion is surrounded by the beauties of the natural world, and yet no help comes from the hills. St. Mark’s stands at the heart of Venice, and yet its beauty has in no way prevented the moral decline of the city. Nature, and art the interpreter of nature, are unable to redeem society, therefore the proposition must be reversed: redeem society, and the significance of art and nature may once more be appreciated by mankind. Tintoretto failed to save Venice; could a renewed Venice, that is to say England, save Tintoretto? The importance of art as a moral activity remains; beauty still exists to convey the absolute values upon which a sound society must rest; but if the art of a nation is beautiful, it is because its society is noble, and Victorian art is ugly because Victorian society is ugly. As early as 1847 he had written: ‘There has not before appeared a race like that of civilized Europe at this day, thoughtfully unproductive of all art — ambitious — industrious — investigative — reflective, and incapable’ (12.169). The opening lines of The Stones of Venice were a solemn and explicit warning to the England of his day. [133/134]

‘St. Mark’s’ may show that art could not save the Venetians from their fall — but it does not show how the ruin of their art itself occurred. And here we are back among questions that seem primarily aesthetic rather than sociological. However, when Ruskin comes to examine the reasons for the decline of Venetian Gothic architecture, social conclusions are inescapable. The point is sometimes overlooked that he did not study Venetian architecture because he considered it the best form of Gothic — his opinion of Verona was far higher — but because Venice ‘exemplifies, in the smallest compass, the most interesting facts of architectural history’ (8.13). Venice was a model that would show just that interconnection between aesthetic and social questions which make art a moral activity.

Like Pugin, Ruskin believed that the Renaissance revival of Greek and Roman architecture was not the cause of the fall of the Gothic, but its expression. Gothic was corrupted from within, just as the Church was corrupted by its own members. In his view the decline of religious art led on the one hand to the rejection of art by the Protestant reformers, and on the other made way for a takeover by Paganism which took artists away from faith to fiction, and caused the debasement of all art values. The cause of this collapse must therefore be found within the Gothic period, and must be detectable in the fabric of the buildings themselves. In accordance with his established practice, he relied almost entirely on the observing eye alone, for no historians agreed on the dates of the buildings considered.

Making the same calculations with the same techniques that had been applied to painting, Ruskin came to the same conclusion: that the Gothic had sown the seeds of its own destruction the moment it violated truth. The truth of Gothic tracery was its organic form — not as flowers or leaves — but as stone. As the carver refined his skills, however, he discovered that stone could be made to appear to bend or curve, as though it were malleable, and a lie was told. When

the tracery is assumed to be as yielding as a silken cord; when the whole fragility, elasticity, and weight of the material are to the eye, if not in terms, denied, when all the art of the architect is applied to disprove the first conditions of his working, and the first attributes of his materials; this is a deliberate treachery. [8.92]

The pleasure of flowing tracery is undeniable, but once the builder is distracted from the space he has to fill to the mere means of filling it, then mannerism, with its ensuing degradation, is inevitable. Once free of the laws of physics, tracery could disobey all the laws of organic [134/135] form: stone bars could appear to flow through one another, the principal mass of a pillar could look as though it had been poured over the smaller shafts supporting it. For the fourteenth-century builder the display of technical skill became the sole object of architecture.

The question was not now with him, What can I represent? but, How high can I build — how wonderfully can I hang this arch in air, or weave this tracery across the clouds? And the catastrophe was instant and irrevocable. Architecture became in France a mere web of waving lines, — in England a mere grating of perpendicular ones. [16.283]

The cause of this collapse was, paradoxically, perfection. Once Art becomes interested only in herself, ‘she begins to contemplate that perfection, and to imitate it, and deduce rules and forms from it; and thus to forget her duty and ministry as the interpreter and discoverer of Truth’ — clearly Ruskin intends this truth to be both moral and aesthetic — ‘by her own fall — so far as she has influence — she accelerates the ruin of the nation by which she is practised’ (16.269).

Perfection led to self-regarding mannerism, luxury, vice. The great virtue of the Gothic had been that it had room for imperfection. The medieval carver practised the Christian virtue of humility before the stone, he did his best, to the limit of his capabilities, and so reached a fulfilment of his creative potential that would be impossible in a form of architecture that imposed an absolute standard of execution and a rigid repetition of parts. When Ruskin wrote that the glory of Gothic was that ‘every jot and tittle, every point and niche of it, affords room, fuel, and focus for individual fire’ (9.291), he meant that the medieval cathedrals expressed just those values of life and energy which he found in nature, and sought to release in society.

The doctrine of the evils of perfection was found in the traceries of Rouen and the pillars of Abbeville — but the sociological conclusions quickly followed. They are drawn in a chapter in the second volume of The Stones of Venice, ‘The Nature of Gothic,’ which follows shortly after that on St. Mark’s. Perfection, it is argued, enslaves the artist, by preventing individual expression. This applies to all manual labour, for in any man ‘there are some powers for better things; some tardy imagination, torpid capacity of emotion, tottering steps of thought’ (10.191), but they can be utilized only if we are prepared to allow for individual imperfection. Almost imperceptibly Ruskin has ceased to talk about the artist, and begun to discuss the worker. His concern is no longer fifteenth-century Venice, but nineteenth-century England, for the perfectionism of the industrial age has made men again into slaves. The [135/136] standard imposed upon the craftsman is not that of nature, but of the machine; if he is to be liberated, he must be allowed to think, instead of made to copy. Even if the results are crude and feeble, ‘you have made a man of him for all that. He was only a machine before, an animated tool’ (10.192).

Ruskin blames the dehumanization produced by industrial society more than anything else for the political upheavals taking place around him. The cause of social discontent was not really hunger, or envy, but the very system which the Utilitarian economists since Adam Smith had regarded as opening the way to universal happiness. An essential element in the organization of production is the division of labour; but for Ruskin,

It is not, truly speaking, the labour that is divided; but the men: — Divided into mere segments of men — broken into small fragments and crumbs of life; so that all the little piece of intelligence that is left in a man is not enough to make a pin, or a nail, but exhausts itself in making the point of a pin or the head of a nail. [10.196]

This is a conscious reference to Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, for he too takes pin making as an example of the division of labour (vol. 1, 8). But where Smith sees a system which gives each man but one thing to do as efficient and productive, Ruskin sees the process breaking down the organic unity of life into sterile units of despair.

The analysis of the social conditions of industrialization in ‘The Nature of Gothic’ has a parallel in another consideration of the conditions of labour in the mid-nineteenth century: Karl Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Here Marx uses the term ‘alienation’ to describe many of the consequences of industrialization which Ruskin also deplored. Man is alienated from nature; for the product of his labour, his connection with the natural world, is taken from him. His labour is not satisfying in itself, for he does not look upon it as in any way a creation of his own, but rather as an abstract commodity which must be exchanged for the necessities of existence. Since his work does not release any creative potential, man is alienated from his own self, having no means of transforming the external world in accordance with his self-defining instincts. Alienated from himself, man is also alienated from others in the struggle for survival. Without using a single term such as ‘alienation,’ Ruskin makes the same points: the dislocation of man and nature, the status of man reduced to that of a machine, work as slavery when creativity is stifled, man set against man by the laws of competition.18 [136/137]

I stress that I am pointing to a parallel, not a connection. Marx’s early writings on alienation were not published until 1932. But that there should be a parallel is not surprising: both men were describing the same economic conditions and had read the same theorists, notably Adam Smith and Ricardo, with perhaps a backward glance at Rousseau. Marx’s more philosophically expressed analysis throws considerable light on the conclusions that Ruskin was approaching through aesthetic terms. Both believed that the essential relationship was between man and nature, and that the medium of this relationship was work: not simply the economic tasks forced upon man by necessity, but the constant activity by which man transforms his environment at the same time as he is shaped by it. For Ruskin the highest mode of this activity was art, but as ‘The Nature of Gothic’ shows, he sought to raise all human labour to its most creative level.

Both Ruskin and Marx opposed the utilitarian economics of their day, the ‘classical’ economics which assumed that egoism was the principal motivation of man, but that the checks and balances of competition would resolve individual conflict for the general good. Both argued that we must transcend egoism by recognizing that our activities are governed by what exists between people, and links them, not by an abstraction within ourselves that separates us from others. The radical difference is in how they thought this fellowship could be achieved. Marx predicted a series of revolutions, more or less violent; Ruskin, with his religious upbringing, restricted the possibilities of conversion to each individual, rather than a whole class.

The attack on contemporary working conditions in ‘The Nature of Gothic’ is only a relatively small portion of the whole chapter; it grows naturally out of a consideration of the conditions of labour needed to produce good architecture, and leads on naturally to the prescription of principles for contemporary design, and to an attack on demands for perfection in all art. Increasingly, however, he saw the life of the worker as an essential link in his argument for a man-centred art. The conclusion to The Stones of Venice repeats the thesis that contemporary society demanded above all the perfection and accuracy of

hand-work and head-work; whereas heart-work, which is the one work we want, is not only independent of both, but often, in great degree, inconsistent with either. Here, therefore, let me finally and firmly enunciate the great principle to which all that has hitherto been stated is subservient: — that art is valuable or otherwise only as it expresses the personality, activity, and living perception of a good and great human soul. [11.201] [137/138]

He feared that the point might not get across, tersely remarking in 1854 that no one had ‘yet made a single comment on what was precisely and accurately the most important chapter in the whole book; namely the description of the nature of Gothic architecture, as involving the liberty of the workman’ (12.101). Yet ‘The Nature of Gothic’ was twice chosen as a manifesto for a new ordering of society, first by the Working Men’s College in London, founded by the Christian Socialist F. D. Maurice in 1854, and then by William Morris, who reprinted the chapter at the Kelmscott press in 1892. Morris’s admiration for both Ruskin and Marx is one sign of affinity between The Stones of Venice and Das Kapital.

A developing concern for the ethics of production and consumption found its first expression in concern for the production and consumption of artists. It is in these ironic terms that two lectures on art education given at Manchester in 1857 are couched. Their title, The Political Economy of Art, is doubly ironic, for the occasion was the great Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, held in the city which had given its name to the utilitarian economics he despised. A series of lectures and addresses throughout the 1850s repeats the argument of The Stones of Venice, that even with great art a nation can lose its way.

The lectures continally reach out towards a wider context, where the relationship between the artist and society might be defined for once and for all. That meant writing directly about society itself. Criticism of contemporary values was not new; Thomas Carlyle had been denouncing society’s wickedness for twenty years, and the development of a personal friendship increased Carlyle’s influence upon him. But Ruskin differed from other critics, whether novelists like Dickens or sages like Carlyle, in that he attacked the Utilitarians on their own ground. He was the only one to attempt to write a work of economics.

The opportunity for such a startling change of subject came in 1860, shortly after the publication of the last volume of Modern Painters. His publishers had launched a new magazine, The Cornhill, edited by Thackeray, and, having obtained his father’s grudging consent, he offered them a series of articles on political economy under the general title Unto this last. It must be admitted that his knowledge of theoretical economics was limited; one could hardly be more frank than Ruskin himself, who once boasted that he had never read a single work of economics, except Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations twenty years before (16.10). Clearly he made some preparations for Unto this last by reading David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill, from whose works [138/139] quotations appear, somewhat inaccurately, in the essays.19 It must also be admitted that, when practical questions of economics are tackled, solutions are close to those of the writers he criticizes. But these limitations do not weaken the essential point of Ruskin’s argument, that it was necessary to place the science of economics on an ethical basis. One measure of his success may be the fact that the articles in The Cornhill caused such an outrage that they were stopped before the series was complete.

People were angry, because Unto this last exposed the blind selfishness which lay beneath the complacent belief that to act in one’s own interests was also to act in the interests of society. Jeremy Bentham’s proposition that man’s actions are governed by the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain had led the economists to argue that individual selfishness created a natural harmony of interest in society, that this harmony was spontaneous and beneficent, and that the less that was done to interfere with it the better. Ruskin interpreted the classical economists as saying: ‘avarice and the desire of progress are constant elements. Let us eliminate the inconstants, and, considering the human being merely as a covetous machine, examine by what laws of labour, purchase, and sale, the greatest accumulative result in wealth is obtainable’ (17.25). What was especially alarming was that the economists were happy that affairs should be regulated by a blind process devoid of moral content. The law of supply and demand was in economics the equivalent of the ‘balances of expediency’ (17.28) which governed utilitarian ethics. The rule that when supply exceeds demand, prices fall, and when demand exceeds supply, prices rise, is morally neutral, but its consequences can be horrifying, as anyone who had lived through the economic upheavals of the 1830s and 1840s could see.

The Utilitarians, Ruskin pointed out, applied the law of supply and demand to people as well as products. Adam Smith had seen this as the regulator of population growth, and the Reverend Thomas Malthus had provided a rationale against charity by showing that the poor bred to the limit of their capacity to support children, so that any improvement in their conditions would only lead to a population surplus. As a result, the poor ‘are themselves the cause of their own poverty,’ which must have been very comforting to a rich man.20 Ruskin satirized this attitude in a letter to the Daily Telegraph in 1864, pointing out that the oppressed labourer would conclude that ‘the shortest way of dealing with this ‘‘darned’’ supply of labourers will be by knocking some of them down, or otherwise disabling them’ (17.502). [139/140]

In place of the naked competition which seemed the only motivation of nineteenth-century society, Ruskin offered cooperation, social affection and justice. It was simply not true that egoism was our guiding principle, and it certainly did not produce the beneficent results the Utilitarians claimed. Cooperation — that essential quality in art — would end the destructive antagonism of rich and poor, and instead society would be ordered in accordance with the principle of justice. Ruskinian justice is essentially authoritarian: it would bring equity, but not equality, for each would find his place in society according to his merits, the apportionment in accordance with moral law. The type of Divine justice in Modern Painters 2 is Symmetry; but ‘Absolute equality is not required, still less absolute similarity’ (4.125). It is a concept that derives from the Evangelical idea of God, the Hebrew God of the Old Testament, the angry father whose judgment of the sinful and the elect needs no explanation. The angry father could however also love and show compassion, and Ruskin’s relations with his own father play their part in his respect for paternalist authority. To the Biblical concept of justice was added that of Plato’s Republic, where a state founded on mutually cooperating classes was ruled by an elite of benevolent leaders. In the final analysis Ruskin’s concept remains unphilosophical, a projection of his conscience, or even an emotional expression of a need for security. But it becomes comprehensible when one realizes that it is the expression, in moral terms, of just those principles of right ordering and cooperation which govern his aesthetic theories.

Having placed the economic argument on an ethical plane, he was able to point to an essential flaw in the economists' case. Adam Smith and David Ricardo recognized that the only real source of value was labour. Capital, as tools or land, was useless without hands to work it; the capitalist made his profit by lending the labourer the wherewithal to live in return for working with his capital. Labour transformed capital by making it fruitful — but the fruits went to the capitalist, not to the labourer. Ruskin accepted that labour was the source of value, as indeed did Marx, but he pointed out that therefore there was a social relationship which must be taken into account. It might appear sound economic sense to buy cheap and sell dear, but whenever we buy cheap goods, ‘remember we are stealing somebody’s labour. Don’t let us mince the matter. I say, in plain Saxon, STEALING — taking from him the proper rewards of his work, and putting it into our own pocket’ (l6.401-02). It is useless for one man to make himself rich, if he makes two men poor in the process. The economists held that what was good for one man [140/141] was good for society; the moral argument was that it was not a question of the acquisition of wealth at all, but how it was acquired, and how it was used. And since riches meant power over other people, wealth should be calculated in terms of the value of the people whose work it commands.

But what does that vague word ‘value’ really mean? Here again there was an error to be shown in the economists’ calculations. In practice, value was treated as value in exchange, and it was on the basis of what one could get in exchange for a given article that one calculated its price. Value in exchange was governed by the law of supply and demand, which should in theory bring prices to their lowest practical level. But if supply and demand forced the price of labour down to starvation wages the calculation was futile, and the injustice hurt worker and master alike.

What made your market cheap? Charcoal may be cheap among your roof timbers after a fire, and bricks may be cheap in your streets after an earthquake; but fire and earthquake may not therefore be national benefits. Sell in the dearest? — yes, truly; but what made your market dear? You sold your bread well today; was it to a dying man who gave his last coin for it? [17.53-54]

The value of something is not its price, nor its value in exchange, but what prompted us to make an exchange for it in the first place, the fact that we had a use for it, that it was of value to us.

Ruskin argues that our calculations should be based not on value in exchange, but value in use, utility. It is no longer a question of the abstract and remorseless law of supply and demand, but the completely human problem of differing capacities and desires: wealth must be of use for someone, consumption must do us good, not harm. What governs that use is the principle of justice, and the test of utility; both ideas undermine the basis of orthodox economic thinking and establish a fresh set of values on which to establish a new social philosophy. The essence of that philosophy is that things are valuable only if they ‘avail towards life’ (17.84), that wealth is ‘THE POSSESSION OF THE VALUABLE BY THE VALIANT’ (17.88), and that there is but one fact to be remembered in all our economic dealings: ‘THERE IS NO WEALTH BUT LIFE’ (17.105).

The imagery of Unto this last rests upon a fundamental opposition of life and light, and death and darkness, and to a great extent, whatever our opinion of the ‘scientific’ content, the argument also rests on this antithesis. It does not weaken Ruskin’s case to say so, for the practical consequences of nineteenth-century economic policies were death and [141/142] disease for the exploited, and quite literally darkness, as he was to point out in his meteorological observations in The Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (1884). The positive values of a free, happy, organic and creative society are associated with ideas of life and light. Life, as we have seen, is that force in the natural world which art and architecture should convey to man, and light is one of its purest expressions, a Divine attribute listed in Modern Painters 2 as the type of Purity conveyed in Scripture by ‘God is light, and in him there is no darkness at all’ (I John 1: 5). As we have seen, Ruskin was no longer an Evangelical, but he had developed the use of typology into a system of universal symbolization. The opposition of light and darkness is not only an Evangelical type; it is also an archetype, and would be recognized instinctively:

To the Persian, the Greek, and the Christian, the sense of power of the God of Light has been one and the same. That power is not merely in teaching or protecting, but in the enforcement of purity of body, and of equity or justice in the heart; and this observe, not heavenly purity, nor final justice; but now, and here, actual purity in the midst of the world’s foulness, — practical justice in the midst of the world’s iniquity. [22.204]

The archetype is completed by its opposites, death and darkness. The forces of the Devil which had contended for the young Ruskin’s Evangelical soul were now perceived as a universal evil working to destroy the potentially paradisical garden of England. What the economists thought of as production was in fact destruction. True wealth had its opposite, ‘illth’:

One mass of money is the outcome of action which has created, — another, which has annihilated, — ten times as much in the gathering of it; such and such strong hands have been paralyzed, as if they had been numbed by nightshade: so many strong men’s courage broken, so many productive operations hindered; this and the other false direction given to labour, and lying image of prosperity set up, on Dura plains dug into seven-times-heated furnaces. That which seems to be wealth may in verity be only the gilded index of far-reaching ruin. [17.53]

In these passages Ruskin may sound more like a preacher or a prophet than a philosopher, but the imagery was necessary to persuade men to transcend the narrow limits of economics. The use of the archetypal conflict of life and death was not a mere literary device; he could see that men were killing each other and destroying the world in the search [142/143] for profit. A moral appeal such as this could only be expressed in the strongest imaginative terms.

Unto this last seems such a change of direction that it is often considered as the beginning of the social writings of the 1860s, rather than as the culmination of the art criticism that had gone before. The book is of course both, but I have discussed it before the conclusion to Modern Painters because it is the clearest and most obviously socially directed expression of the theme of life and death that runs throughout Modern Painters and the architectural writings. The direct attack on economics brings the theme out into the open. But where does the argument for social reform leave the artist? Should he abandon painting and take up economics? Far from it. Like Ruskin, he should be concerned with both.

To begin with, the conclusions drawn from the analysis of industrialization in ‘The Nature of Gothic’ apply just as much to the artist as to the worker. The artist is after all a worker himself, and every worker should be as far as possible an artist. Later, Ruskin was to lay stress on the origins of art in manual labour to the extent of saying that ‘a true artist is only a beautiful development of tailor or carpenter’ (27.186). Art, as has been said, was the highest form of that activity in which we are perpetually engaged, the constant interchange between ourselves and our environment which, as Marx pointed out, is for most of us no more than work. Since art is the highest form of work, the artist must be a special kind of person, a special kind of worker, and in as much as art contains the history of the whole race that produces it, the artist will embody in his own personality the distinctive characteristics of the society which produced him.

The idea is close to Carlyle’s image of the creative man as hero, a Romantic concept derived from Goethe, and indeed Carlyle said of Goethe that he was ‘a clear and universal Man’ whose sympathy for the ways of all men ‘qualify him to stand forth, not only as the literary ornament, but in many respects too as the Teacher and exemplar of his age’ (208). But where Carlyle treats his heroes very much as actors upon history, Ruskin was more concerned to show how artists expressed through their actions the historical conditions that prevailed upon them. He hoped that they would indeed become the teachers of the rest of mankind, but it was as exemplars that he saw them. The most significant example of all was Turner, a product of his time, rejected by society when he sought to influence it, and yet whose rejection showed how important that interaction with society was. And if Turner [143/144] typifies for Ruskin the social conditions of art in the first half of the nineteenth century, his handling in Modern Painters typifies the changes that took place in Ruskin’s own viewpoint. At the beginning Turner is presented as close to a Romantic poet, like Wordsworth; at the end he is nearer to Carlyle.

Artists, then, are the expression of their society, and at the same time give form to their society through their art. It had been part of Ruskin’s argument since Modern Painters 1 that an artist could only work within his local traditions: ‘The Madonna of Raffaelle was born on the Urbino mountains, Ghirlandajo’s is a Florentine, Bellini’s a Venetian; there is not the slightest effort on the part of any of these great men to paint her as a Jewess’ (3.229). The changes that come about in art take place for common reasons of national character, and take place simultaneously in accordance with both social and individual developments.

The consequence of the relationship with national character is that the artist has a special moral responsibility to the society he serves. If he is indeed to embody all the noble virtues of his time, he must be noble himself, ‘no shallow or petty person can paint. Mere cleverness or special gift never made an artist. It is only perfectness of mind, unity, depth, decision, — the highest qualities, in fine, of the intellect, which will form the imagination’ (7.249). But he should exercise these virtues only through the use of his recording eye — and here there is a clear distinction between Ruskin’s and Carlyle’s heroes: ‘It is not his business either to think, to judge, to argue, or to know. His place is neither in the closet, nor on the bench, nor at the bar, nor in the library. They are for other men, and other work . . . the work of his life is to be two-fold only; to see, to feel’ (11.49).

It is tempting to conclude from this that Ruskin is saying that in order to be a good painter one must also be a virtuous man, and for a time it appeared that he did hold this view. From an article written in 1847 it seemed that Fra Angelico was his ideal artist, ‘a man of (humanly speaking) perfect piety — humility, charity and faith’ (12.241). But, as we know from the account of Ruskin’s ‘unconversion,’ he came to accept the animality of man, and changed his heroes accordingly. What gave him particular trouble (and I do not believe he ever found a satisfactory solution to the problem) was the fact that the flowering of art seemed inevitably to herald the destruction of the society that produced it. One explanation was that as exemplars of their age, artists must necessarily fall with it. The fall itself was manifested in the same way in architecture: the demand for perfection, and the artist’s increas-[144/145]ing capacity to achieve it, led to a self-regarding interest in skill alone. At first the Renaissance provided a healthy stimulus and an antidote to corrupt Gothic, and produced painters like Michelangelo, Leonardo and Raphael; but inevitably their achievements and the weakening of the religious impulse in society led to a luxurious and vicious mannerism. Painting and sculpture survived the immediate collapse of architecture because they were the individual products of the finest minds. To borrow an idea from Marx: artists like Tintoretto, Titian and Veronese resisted alienation because of the individual nature of their works; but not those who followed. Sadly, it seemed to Ruskin, ‘the names of great painters are like passing bells’ (16.342). A significant death image.

It was only when the view of the artist as an expression of society had been formulated that Ruskin could come to terms with the sixteenth-century Venetian painters. The preface to Modern Painters 5 admits that until then they had been treated as ‘however powerful, yet partly luxurious and sensual’ (7.9). It was not until that moment in the Gallery of Turin before Veronese’s Solomon and the Queen of Sheba that he was finally able to shrug off the religious prejudice in favour of specifically God-directed art: ‘with much consternation, but more delight, I found that I had never got to the roots of the moral power of the Venetians’ (7.6). As a result, not the ascetic Fra Angelico but Titian becomes the ideal artist,

wholly realist, universal, and manly. In its breadth and realism, the painter saw that the sensual passion in man was, not only a fact, but a Divine fact; the human creature, though the highest of the animals, was, nevertheless, a perfect animal, and his happiness, health, and nobleness, depended on the due power of every animal passion, as well as the cultivation of every spiritual tendency. [7.296-97]

This act of integration is the true theme of Ruskin’s own all-important un-conversion before Veronese. He was at last able to explain how it was that the Venetian painters, although without religion, were yet great artists, for

human work must be done honourably and thoroughly, because we are now Men; — whether we ever expect to be angels, or were slugs, being practically no matter. We are now Human creatures, and must, at our peril, do Human — that is to say, affectionate, honest, and earnest work. Farther I found, and have always since taught, and do teach, and shall teach, I doubt not, till I die, that in resolving to do our work well, is the only sound foundation of any religion whatsoever. [29.88] [145/146]

The act of integration represented by the moment in the Turin gallery enabled Ruskin at last to try to bring Modern Painters to a conclusion. In spite of its occasional discursiveness, the last section is a remarkable synthesis of the recurring themes and ideas of those five volumes. A synthesis, and a resolution, for many of the ideas that had been subjected to a constant dialectical evolution find their final form. There is no better example of this than the return in the opening page to the starting-point of Modern Painters, the relationship between man and landscape. ‘The Moral of Landscape,’ the half-way position, questioned the value of actual landscape to man; here the value of landscape painting is finally decided upon. As has been inevitable ever since the antithetical chapters on ‘Mountain Gloom’ and ‘Mountain Glory,’ the conclusion is that landscape is valuable only in its relation to man.

As is so often the case in Ruskin’s later writings, the title of the chapter itself is a poetic image of its contents. Here ‘The Dark Mirror’ conveys the final conception of a man-centred art. The image of the mirror, so vital to his explanation of the significance of symbolism and the workings of the imagination, reappears as what it always had been, the image of the soul. His original inspirations, nature and the Bible, are finally placed in their right relationship to man, for it is only through man that their truths can be perceived. Only in the dark mirror of the soul will we find a true conception of God: ‘No other book, nor fragment of book, than that, will you ever find: no velvet-bound missal, nor frankincensed manuscript; nothing hieroglyphic nor cuneiform ; papyrus and pyramid are silent on this matter; — nothing in the clouds above nor in the earth beneath’ (7.261-62). This commitment to the human soul may leave Ruskin staring into a scarcely penetrable gloom, ‘Through the glass, darkly.’ But, he continues, ‘except through the glass, in nowise.’ Against this darkness is set an image of light, as man is shown to illuminate the world around him, for ‘all the power of nature depends on subjection to the human soul. Man is the sun of the world; more than the real sun’ (7.262).

The end of Modern Painters 5 involves one last grand view of the cultural history of Europe, a historical analysis which resolves itself into how each period and each school of art came to terms with the concept of death. Death, as we know from the imagery of Unto this last, is not merely the final act of life, but its positive antagonist, an essential antagonist, however, for schools of art are strengthened by their struggle, and can only be judged by their victory over it. Thus the school of pre-Renaissance religious painting ‘cannot constitute a real school [of landscape], because its first assumption is false, namely, that [146/147] the natural world can be represented without the element of death’ (7.265). The struggle is most heroic amongst the Venetians, and its result the most tragic, for they threw away their power over Venice in the pursuit of pleasure. Through a series of contrasted artists set in their contrasted landscapes, we arrive at one last great antithesis, Giorgione’s Venice versus Turner’s London.

Against the beauty of Venice is set the squalor of London; against the luxurious but none the less proud religion of Venice is set the almost complete absence of religion in Turner’s city. The ugliness of London had its compensations, for it caused Turner to know and understand the poor, but he could not find God there. Only outside the town, among the Yorkshire hills, could Turner find the beauty which gave rise to faith — or creative inspiration: ‘Loveliness at last. It is here then, among these deserted vales! Not among men’ (7.384).

So Turner chose to paint landscape, where Giorgione, with the architecture of a beautiful city around him, could still find beauty among men. Turner ‘must be a painter of the strength of nature, there was no beauty elsewhere than in that; he must paint also the labour and the sorrow and passing away of men: this was the great human truth visible to him. Their labour, their sorrow, and their death’ (7.385-86). And so Ruskin begins a long meditation on the death of the nineteenth century, a meditation which finds its issue in the analysis of those two final Turner canvases, The Garden of the Hesperides and Apollo and Python.