At the beginning of 1866, Ruskin was planning, or at least hoping, to remarry. He had become deeply attached to a young Irish girl, Rose La Touche (1848-1875) whom he had first met in 1858; she was then aged ten, he was thirty-nine. His proposal of marriage was neither accepted nor rejected by the eighteen-year-old; she kept him in suspense, asking him to wait three years for an answer. Rose's parents vehemently opposed the marriage; at one point, Effie Millais intervened and objected on the grounds that her former husband was not free to remarry under the terms of the annulment of 1854. In any case, Ruskin himself agonised over what Rose's decision would eventually be. He became more and more distraught. Rose's feelings oscillated between obsession and hatred. At a casual meeting in the Royal Academy on 7 January 1870, she rebuffed him: her ostensible reason was religious incompatibility.

Ruskin had had unrealistic expectations from the relationship. It was almost a kind of imaginary, phantom love. Virginal Rose was inaccessible most of the time, and Ruskin projected his feelings upon her and created an idealised couple, not unlike the way in which he reacted to Effie before their marriage. The relationship was flimsy, yet troubled, and it haunted Ruskin for the rest of his life. It destabilised him and at times he reverted to infantile behaviour and language, almost a kind of protection as he expressed his need to be cared for and loved by a female. Rose withdrew from Ruskin emotionally and physically; she was suffering from symptoms of anorexia and had psychiatric problems. She was also excessively pious. Ruskin's sketch of Rose on her deathbed captures the wasted life of the young woman, her hysteria and the demise of his longed-for happiness with her.

On Ruskin's return from a three-month continental tour in France and Switzerland, Gordon was at Denmark Hill for dinner "unexpectedly" on 26 July (Diaries, II, 595). In late August, he was invited to dinner where he made the acquaintance of William Henry Harrison, Ruskin’s "first editor" (of the magazine Friendship’s Offering) who had published many of the aspiring writer’s poems (Diaries, II, 598). Gordon also came to know Joan (Joanna) Agnew (future Joan Severn) who was now living at Denmark Hill as a companion for Margaret Ruskin. Gordon and Joan became good friends and frequently corresponded over many years. Another visit by Gordon was noted in Ruskin's diary on 8 November (Diaries, II, 602).

Ruskin's physical and emotional health continued to be poor. "Frightly tormented in various ways", he wrote in his diary in January 1867 (Diaries, II, 609). His mother's health was also poor – her sight was failing and her son thought she would not live beyond the spring. But a suggestion he received from Thomas Dixon, a cork-cutter from Sunderland in the industrial north-east of England, asking for copies of his writings on political economy, prompted him to commence a regular series of public letters or pamphlets on a range of socio-economic issues. This was to become Time and Tide and provided Ruskin with a focus for his work.

Ruskin by Hubert von Herkomer (at left) and W. Roffe (39 frontispiece).

Meanwhile, during the bitter frost and snow in the first months of 1867, Ruskin devoted time to Gordon and the Pritchards. Gordon was invited to dinner on several occasions at Denmark Hill and Ruskin made a point of visiting the Pritchards at their London home. The relevant diary entries are:

15 January Tuesday "Browning called. Gordon at dinner" (Diaries, II, 608).

13 March Wednesday "Called on Mrs Pritchard" (Diaries, II, 613).

18 March Monday " Bitter frost and snow. Sent off conclusion letter on prodigal son to Dixon. Gordon at dinner with Joan and me alone" (Diaries, II, 613).

2 April Tuesday "Drove in with Joanna, to call on Mrs Pritchard. Waited in vain" (Diaries, II, 614). 15 April Monday "Gordon dines with us" (Diaries, II, 616).

26 April Friday "Gordon and T. Richmond in evening" (Diaries, II, 616).

9 May "Into town. Call at Mr Pritchard’s – found riding school! (Con and Mrs H[illiard] at lunch)" (Diaries, II, 617).

28 May Tuesday "Mrs Pritchard called" (Diaries, II, 619).

Ruskin spent the Whitsun weekend, 8-10 June 1867, chez Gordon at Easthampstead, no doubt hoping to have some moments of calm and respite from his anxiety about Rose. Before setting off on Saturday 8 June, he "read 10th Psalm in R[ose]’s book [and] planned [a] commentary on it. [Then] down to Gordon’s" (Diaries, II, 620). After the main church services on Whitsunday, Gordon and Ruskin "drove through pine woods to Sandhurst" (Diaries, II, 620), a few miles to the south. This relaxing ride and Gordon’s reassuring company and wise counsel about Rose contributed a little to his recovery. He returned to Denmark Hill on Monday 10 June "in lovely day, but sad in evening" (Diaries, II, 620).

In early autumn (on 9 October 1867), Gordon travelled to Ireland for the wedding of his neighbour Lady Alice Hill (daughter of the Marquis of Downshire) and Lord Kenlis at Hillsborough (County Down). He was invited not only as a guest but he had a religious role. Along with the Venerable the Archdeacon of Down and the Rev. St. George, he assisted the Lord Bishop of Down and Connor in the performance of the marriage ceremony. It was a glittering occasion and in the evening the town was illuminated and bonfires blazed on the surrounding hills. On 11 October 1867 The Times reported that the festivities would continue on the Downshire estates "for some days" (9).

1868 continued to be a time of emotional turmoil with strain and uncertainties surrounding his relationship with Rose La Touche. In early March Ruskin consulted with his medical friend Dr John Simon about the nature of Rose's mysterious illness(es), suggesting to him that she might have some kind of "fatty degeneration" or heart disease. The reply was not particularly reassuring:

The "fatty degeneration" is something in which I should ask you not to believe except of first-rate medical authority. [...] My knowledge of your will-o'-the-wisp is neither much nor recent; but such impression of it as I have leads me to extreme a priori scepticism as to have her having any true signs of the disease. [...] Fearfully and wonderfully made are the insides of hysterically-minded young women. [...] If there is really anything beyond co-feminising twaddle to justify a suspicion of organic heart-disease of any kind, by all means get a conclusive medical opinion. [Hilton, Later Years 146-47]

Ruskin's tortured sexuality and suppressed desire for Rose, transferred to Joan Agnew, manifest themselves at this time in a snake dream charged with sexual overtones:

Dreamed of walk with Joan and Connie [Hilliard], in which I took all the short cuts over the fields, and sent them round by the road, and then came back with them jumping up and down banks of earth, which I saw at last were washed away below by a stream. Then of showing Joanna a beautiful snake, which I told her was an innocent one; it had a slender neck and a green ring round it, and I made her feel its scales. Then she made me feel it, and it became a fat thing, like a leech, and adhered to my hand, so that I could hardly pull it off – and so I woke. [Diaries, II, 644]

Gordon's visit to Ruskin very soon after receiving that letter from Dr Simon, and after the snake dream, may have been to provide his friend with comfort and advice. The diary entry of 10 March reads: "Gordon in evening" (Diaries, II, 644).

Margaret Ruskin by Sir James Northcote, RA. Oil on canvas. Source: 35.126.

Margaret Ruskin presided as a martinet at Denmark Hill, but she was kindly towards Gordon whom she considered to have a beneficial influence on her son. They also found common ground for Gordon and Margaret Ruskin shared an interest in farming. Margaret Ruskin's seven acres of land were tiny compared to Gordon's ninety-three acres. In Praeterita, Ruskin described the land – a small farm – behind the house at Denmark Hill and his mother's enjoyment working in gardening and her pleasure and pride in managing the estate: "My mother did like arranging the rows of pots in the big greenhouse; […] And we bought three cows, and skimmed our own cream, and churned our own butter. And there was a stable, and a farmyard, and a haystack, and a pigstye, and a porter's lodge" (35.317-318). There were also orchards, vegetable and flower gardens, chickens and hens. The Ruskin family and staff were almost, if not entirely, self-sufficient in food (perhaps apart from flour?) – and plentiful supplies of wine were in the cellars. The cows were particularly dear to Margaret Ruskin, and as early as 1845 she was extolling their virtues and writing to her son that "the white of our Cows is so purely white" (Letters from Italy 243). So when Gordon lost one of his calves at Easthampstead in May 1868, she immediately offered to replace it with one of her own. Joan Agnew, who had developed a close relationship with Gordon through his frequent visits to Denmark Hill, relayed his delight and acceptance to Margaret Ruskin: "I have had a note from Mr. Gordon saying how delighted he will be to have the calf any day, especially as one of his cows has lost hers and I am to thank you very very much" (Winnington Letters 617).

St. Wulfran, Abbeville, Seen from the River by John Ruskin. 1868. Graphite, ink, watercolour. and bodycolour on white paper, 34.3 x 50.2 cm. Collection: Lancaster (1100). Christopher Newall points out that that, “was the most finished and ambitious of several large drawings of the collegiate church of St. Wulfran that Ruskin made during a stay in Abbeville from 25 August to 21 October 1868,” represents St. Wulfran's “at a time of day when there was no direct sunlight upon it, so that all the colours of the stone from which it was made, and the tiles of its roof, are suffused into a soft and muted range of warm greys and mauves” (184).

Ruskin's decision to work in Abbeville in late summer/early autumn was a wise one. Abbeville was one of his favourite places. He had found immense joy and happiness there on his very first visit as a boy in 1835. On this 1868 visit, he experienced again that sense of elation and deep satisfaction among the Flamboyant Gothic of St Wulfran's and in the little town of Rue. This two-month stay in Abbeville was the longest and most prolific he ever made; he accomplished "a good spell of work" (Gamble, “Ruskin's Northern France,” 9). The purpose of the visit was to prepare a lecture entitled "The Flamboyant Architecture of the Valley of the Somme" to be given at the Royal Institution, London, on the evening of 29 January 1869. Ruskin prepared over fifty illustrations, many of which were his own drawings. Ruskin also enjoyed the stimulating company, among others, of his American friends Charles Eliot Norton and the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. It was a temporary respite during which he regained his strength and zest for life and work and his delight in travelling abroad.

In the days leading up to his fiftieth birthday, Ruskin was depressed. Even an invitation to dinner at John Pritchard's did not dispel his gloom. He wrote in his diary on 2 February, 1869: "Did duty at the evening dinner – sick and weary beyond all word – at Mr. Pritchard’s" (Diaries, II, 664). Henry James observed a strangeness and sense of disorientation about Ruskin when he visited him in the spring of that year.

Ruskin’s images of Veronese tombs. Left: The Tomb of Can Grande della Scalla, Verona. 1845. Source: 11.90. Middle: Castelbarco Tomb, Verona. 1869 or earlier. Collection: Lancaster. Right: Castelbarco Tomb and Gate, Santa Anastasia, Verona. John Ruskin? c. 1852. Daguerreotype (reversed). Collection: Lancaster.

Ruskin left London on 27 April, with his assistant Arthur Burgess, for the continent; to Verona, where he was gathering information on tombs and to Venice, his first visit since 1852. From Verona, he sent twelve books, unnamed, to various friends including Froude and Gordon (Diaries, II, 672). Whilst abroad, Ruskin learnt that he had been unanimously elected first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University. Preparation for the task and series of important lectures began in early autumn.

Gordon decided to go to Denmark Hill for a short break 4-5 October 1869 soon after Ruskin's return from abroad. Such was their degree of friendship and so relaxed was their relationship that it was understood that Gordon could visit and stay any time he wished. This is exactly what he did! On this occasion Ruskin was obliged to explain, in advance to Mrs Cowper, Gordon's presence at the very special private dinner, on 5 October. The letter reveals much about Gordon's character and the absolute trust between the two men:

Today – by chance – not, I hope – mischance – it happens that my dear old Oxford private tutor – afterwards censor of Christchurch – now Rector of East Hampstead – (on the moors of Ascot –), a farming – squire loving – conservative – thoroughly sensible – except for a little (rosy!) edge of Ritualism on the softest leaves of his mind, clergyman of the old school – having always leave to come here whenever he likes, has chosen to come yesterday – and stays until dessert – to-day – leaving about seven oclock – I warn you – that you may not think I asked any one to meet you – and that you may not be checked in anything that might otherwise have been talked about – even at dinner – by Osborne Gordon's seemingly light or somewhat careless maner – which is indeed the veil that this kind of Englishman always manages to throw over what is best in him – complicated in Gordon with a curious sort of cheerful despair about old toryism, which he intensely worships in the spirit of it – without seeing his way to do it in the letter – (or motto) also, as we do – because his farmer's "commonsense" trips him up always, the moment he feels himself becoming romantic. [Mount-Temple Letters 225-26]

Also present at this special dinner, arranged at Denmark Hill perhaps at the instigation of Mr and Mrs Cowper, were Laurence Oliphant (1829-1888) and seventeen-year-old Connie Hilliard (1852-1915). It must have been an interesting encounter for Gordon. Oliphant was something of a mystic; he was a colourful character, wealthy, possibly a homosexual and the author of several travel books. He was a keen supporter of the fraudulent English-born American spiritualist medium Thomas Lake Harris (1823-1906), founder of a sect called the Brotherhood of the New Life. Connie Hilliard was the daughter of the Rev. J. C. Hilliard and his wife Mary, of Cowley, near Uxbridge. She was the niece of Lady Trevelyan, Ruskin's loyal friend who had died in Neuchậtel whilst on holiday with him in 1866. Ruskin had first met Connie in 1863 at a tea party the eleven-year-old girl had organised (Hilton, Later Years 101). The conversation turned to spiritualism and perhaps to Rose, for Ruskin derived immense satisfaction from it. He wrote in his diary of 6 October 1869: "Heard marvellous things – Breath of Heaven" (Diaries, II, 681).

Ruskin extended Gordon's circle of friends. At the beginning of November, he took him to dinner at the home of John and Jane Simon, probably at their London home in Great Cumberland Street, where he also met Mr and Mrs Hutchinson (Diaries, II, 686). Mr Hutchinson was most likely Dr (later Sir) Jonathan Hutchinson (1828-1913) who became a surgeon at the London Hospital (1863-1883) in the East End and Hunterian professor of surgery at the Royal College of Surgeons. One of his great discoveries was the identification of three symptoms of congenital syphilis, known as "Hutchinson’s triad". The day after the dinner, Ruskin made a strange comment in his diary: "Had to talk at the Simons’; felt as if silent Mr. Hutchinson thought me conceited" (Diaries, II, 686).

The Royal Academy of Arts, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London.

The promotion to Professor of Fine Art at Oxford did not alleviate Ruskin’s sorrow and highly charged emotional state. His unrealistic hopes of being united with Rose La Touche were dashed by her refusal to speak to him or have anything to do with him at a chance encounter at the Royal Academy in Burlington House on 7 January 1870 (Hilton, Later Years 171-72). Rose had either categorically rejected him or was playing games with him. Ruskin sought to assuage his pain by surrounding himself with a number of interesting and supportive friends. Among these were Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris – both were frequent visitors – invited to dinner on Wednesday 12 January. Consoling and loyal friend Gordon came on Friday 14 January. Perhaps some light entertainment would alleviate Ruskin's distress? That evening, Gordon and Ruskin went to the Haymarket Theatre in central London for a performance of New Men and Old Acres, a comedy by Tom Taylor and A. W. Dubourg (Diaries, II, 693).

But it was not simply to relieve some of his despondency that this play was chosen. Ruskin had a very special interest in it; he knew both the leading lady, his "much-regarded friend" Mrs Madge Kendal (née Robertson) and the co-playwright Tom Taylor, his erstwhile rival for the Slade Professorship at Oxford and a witness on his behalf at the Whistler trial in 1878. Madge Kendal, playing Lilian Vavasour, was already the leading lady at this grand theatre at the age of twenty-one; Jeffrey Richards has described her as "an actress of great verve and charm" (92). But there were other reasons for his interest. The word "Ruskinism" had been coined and became a catchword. In the play, Lilian says of another girl that "in spite of her Ruskinism-run-mad she isn’t half a bad sort" (36.328, note 1). We know of Ruskin’s fascination with reptiles; snakes and serpents were often present in his dreams along with an attractive female presence. New Men and Old Acres provided a memorable example compressed in the short line, "And his wife – well, she’s a caution for snakes!", uttered by Lilian Vavasour. It was not quite a dream, but not quite reality, for here on stage was a beautiful inaccessible woman being linked with venomous reptiles. Ten years later, Ruskin’s lecture at the Royal Institution on 17 March 1880 was entitled "A Caution to Snakes"; he explained to his audience that he had chosen the title "partly in play, and partly in affectionate remembrance of the scene in New Men and Old Acres, in which the phrase became at once so startling and so charming, on the lips of my much-regarded friend, Mrs Kendal" (36.327-28).

After delivering his Inaugural lecture in Oxford on his fifty-first birthday, and successive lectures on art until 23 March, Ruskin soon embarked on another long continental tour – 27 April to 29 July 1870 – mainly in Italy. He generously invited six guests at his expense – or rather at his late father's expense – for three months. These were Joan Agnew, Mary Hilliard and her daughter Connie, and Lucy, the Hilliards' maid, Frederick Crawley, Ruskin's valet, and his gardener, David Downs (Hilton, Later Years 180). The party journeyed from Boulogne to Paris, Geneva, Vevey, Martigny, Brieg and on over the Alps to Milan, Verona and Venice where they spent three weeks.

In Venice, while Ruskin worked on Carpaccio, Brown and Cheney helped to entertain Joan Agnew and the Hilliards with visits to see glass-blowing and gondola building. Ruskin wrote a note of thanks to Brown on 30 May 1870: "My people [...] very happy with you & Mr Cheney today" (Clegg 142). In that same letter, Ruskin revealed his continuing feelings of ambivalence towards Cheney, affection tempered by fear: "I am always terribly afraid of him – & yet very fond of him though he may not believe it" (Clegg 209n). Ruskin was delighted with an arrangement that left him free to carry on with his own work.

On the return journey, they stopped at several other towns in Italy – sometimes zigzagging from one to another – including Florence, Siena (to visit Charles Eliot Norton), Pisa, Padua, Como, then through Switzerland – Bellinzona, Airolo – to Geneva before going back via Paris to Boulogne and England.

These were the dying days of the Second Empire, of the dwindling megalomaniacal power of Napoleon III. His fate was to be sealed on 1 September at the battle of Sedan, a small border town, close to Belgium, on the river Meuse in the French Ardennes, at which his army was defeated and he was captured. Ruskin returned to safety only a few weeks before the commencement of the Franco-Prussian war in which France suffered severe humiliation and the loss of some of her territories in Alsace and parts of Lorraine. Ruskin was far from indifferent to this war.

About two weeks after Ruskin’s return from the continent, Gordon came to dinner at Denmark Hill on Friday 12 August; this was a moment of welcome respite and "pleasant rest" (Diaries, II, 700). He was invited again for dinner on Wednesday 12 October 1870 and was "delightful" (Diaries, II, 705) with Joan Agnew and Lily Armstrong, the attractive young Irish girl whom Henry James met in 1869. Lily Armstrong (later Mrs Kevill-Davis) was a former pupil of Winnington School and she remained a lifelong friend of Ruskin. Ruskin had a short overnight stay at Gordon’s rectory in Easthampstead on the night of Thursday 27 October 1870, returning home on the Friday and experiencing a "various quarrel on the way" (Diaries, II, 705). For whatever reason, Ruskin was concerned that he had not written to Gordon, perhaps to thank him for his hospitality on 27-28 October. He notes in his diary of 3 November: "Must write to Gordon" (Diaries, II, 706).

Ruskin gave a series of lectures in November and December at Oxford on "The Elements of Sculpture", published later under the title Aratra Penteleci ("The Ploughs of Pentelicus"). Instead of residing in the centre of Oxford, he often preferred to stay in the picturesque market town of Abingdon, about eight miles away. He usually stayed at the "Crown and Thistle", a fine seventeenth-century coaching inn with cobbled courtyard, stables and garden, on Bridge Street, close to the river Thames. Several of his letters in Fors were composed at the window of this "quiet English inn" (27.105). From there, he enjoyed the walk into Oxford, chatting to local people on the way and helping anyone in need. On one occasion, he came across a little girl in extreme poverty and saved her from being sent to the "Union" – a workhouse such as the one Henry James visited in Yorkshire at Christmas 1878 – by financing her apprenticeship as a shepherdess on a farm belonging to his friends near Arundel (28.661). That satisfied Ruskin's deep need to have opportunities to change the world.

Gordon was one of Ruskin's guests at Abingdon where, as Ruskin reported to Joan Agnew, "Gordon enjoyed himself" but "found when he came to Oxford, he couldn’t come to lectures at all. So like things always –" (Winnington Letters 670). He initiated Gordon into the delights of this rural English town, whose charms Gordon seemed to prefer to attending Ruskin’s lectures in Oxford!

1871 was a year of many changes for Ruskin. On 20 April 1871, Joan Agnew, Ruskin's ward and his mother's companion for many years, married the painter Arthur Severn, son of Joseph Severn, British Consul in Rome who was best known as the artist in whose arms Keats died. This was not an unexpected event for Ruskin had exercised his authority over Joan and Arthur and insisted on their waiting for three years, a trial period of separation, before marrying (Hilton, Later Years 130-31). Perhaps he hoped the marriage would not take place, for it would disrupt the family dynamics. Ruskin had no choice but to adapt if he wished to remain within this new orbit.

Ruskin's not entirely altruistic wedding present to them was his own childhood home, 28 Herne Hill, with an agreement that he could have use of his old nursery on the top floor. That would be Ruskin's London base until 1888. The domestic arrangements of the Severns and John Ruskin would remain inextricably linked until his death. It was a mutually advantageous situation. The aging, increasingly sick Sage would be looked after by a mother substitute and the Severns had financial security and desirable, free accommodation for life.

Two Views of Brantwood and Coniston Water. Photographs by Simon Cooke.

In the summer of 1871, Ruskin purchased unseen for the sum of £1500, a property known as Brantwood from the radical artist and wood engraver, William James Linton, the estranged husband of Eliza Lynn Linton, the famous anti-feminist. His purchase included a house and fellside grounds above Coniston Water, in the heart of the English Lake District. It was to be his country residence from 1872 and more and more his home as he became increasingly infirm until his death in 1900. It was Ruskin's only home that was ever saved for the Nation, thanks to the intervention of John Howard Whitehouse (1873-1955) in 1932 (Eagles 232-61). 54 Hunter Street, his birthplace, was demolished to make way for the Brunswick Centre, near Russell Square underground station. 163 Denmark Hill was razed to the ground in 1947 and the land used for the building of a large, high-density council estate.

But Brantwood, as Ruskin discovered when he went there for the first time in the autumn of 1871, was in a state of disrepair; it was a huge challenge, responsibility and a constant preoccupation for the new owner. But the location was superb. "I’ve bought a small place here", he wrote to Charles Eliot Norton in September 1871, "with five acres of rock and moor, a streamlet, and I think on the whole the finest view I know in Cumberland or Lancashire, with the sunset visible over the same" (37.35). It was so dilapidated, perhaps more so than Ruskin imagined: "The house – small, old, damp, and smoky-chimneyed – somebody must help me get to rights" (37.35). But owning his very own home, chosen by himself without parental interference, was paramount. He wrote again to Norton of his joy: "Here I have rocks, streams, fresh air, and for the first time in my life, the rest of the purposed home" (37.35).

The year ended with the death of Ruskin’s mother at the age of ninety on 5 December 1871. It had been a slow, lingering decline as he explained to W. H. Harrison: "My Mother has been merely asleep – speaking sometimes in the sleep – these last three weeks. It is not to be called paralysis, nor apoplexy – it is numbness and weakness of all faculty – declining to the grave. Very woeful: and the worst possible sort of death for me to see" (37.43). For the very first time, Ruskin, at the age of fifty-three, was free of parental control.

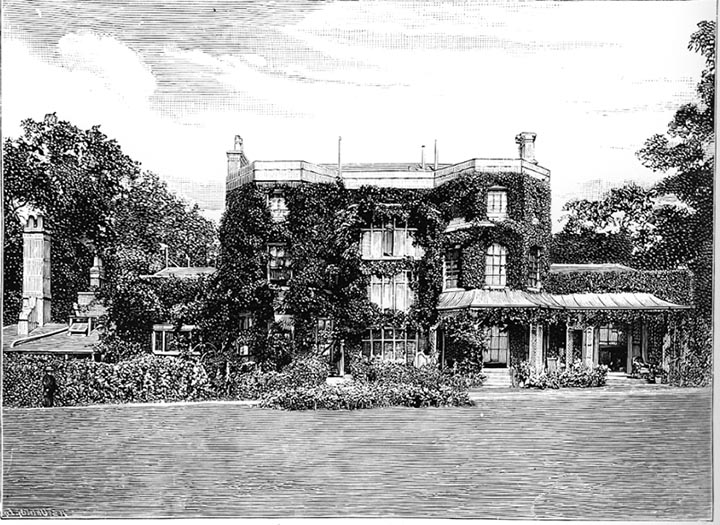

Two Views of Denmark Hill from the Library Edition: The Front and the Back Garden.

Ruskin had the task of preparing the Denmark Hill house for sale. But he was plagued by fits of depression and general illness. At the same time he was finalising his next series of lectures for Oxford. To relieve his ill health and sadness, Ruskin invited Gordon to dine with him at Denmark Hill on 16 January 1872. It was a happy occasion confirmed by the diary entry: "Enjoyed ourselves" (Diaries, II, 718). It was Gordon’s last opportunity to enjoy the elegant house and gardens. Ruskin sold the property shortly after and on Thursday 28 March he vacated it for ever.

But the end of one life marked the beginning of another. One of Ruskin’s first visitors to Brantwood was Gordon who stayed there from Tuesday 8 October until Friday 11 October. It was usual for visitors to Brantwood to be met by carriage off the train at Ulverston, on the West Coast, and then driven approximately thirteen miles inland to Coniston. This was often quicker than taking the train to Coniston on a much longer circuitous route via Barrow and Foxfield. The under-used little Coniston station, the terminus of a branch line from Foxfield Station, was eventually closed, partly due to the decline of the mines, whereas Ulverston remained functional throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries. Gordon was a special guest and Ruskin went in person to meet him at Ulverston. On the way back to Brantwood, they crossed Spark Bridge, then on to Low Nibthwaite approaching the southern tip of Coniston Water. They took the narrow valley road, a stretch of five miles along the eastern shore of the lake with the fells and forests on their right. Almost at the northern tip of the lake, nestling in the hills, was Brantwood, in splendid isolation. From the house, across the lake and soaring beyond the little village (with about the same population as Easthampstead) were the Coniston Fells and immediately opposite was Ruskin’s favourite peak, The Old Man, that he called affectionately the Vecchio.

Two Views of Coniston Water. Left: View from the Painters Glade in early spring by Jacqueline Banerjee. Right: View from Brantwood on a cloudy day by George P. Landow.

The early autumn Lakeland scenery was intensely beautiful with brown and golden hues. The Lake District lived up to its reputation for rain during Gordon’s stay. The diary entries confirm this: ' 10 October. Thursday. "Y[esterday] in pretty showery day to Langdale"; 11 October. Friday. "Y[esterday] pouring all day long"' (Diaries, II, 732). Also staying at Brantwood was Lily Armstrong (the attractive Irish girl whom Gordon had first met in 1870), who had been there since 18 September. Ruskin showed Gordon some of the surrounding area and went to Langdale on Wednesday 9 October, accompanied by Lily Armstrong and Laurence Jermyn Hilliard ("Lollie") (1855-1887), his much-loved friend, secretary, painter and Brantwood neighbour and brother of Connie.

Ruskin was an able, enthusiastic guide who knew the area well. The most likely route to Langdale would have been through the village of Coniston, then in a northerly direction to Yewdale and Skelwith Bridge, skirting Elter Water, through Elterwater village and on to Langdale, in the direction of Ambleside. They were in a part of the country that had been the inspiration for much of Wordsworth’s poetry – the Lakeland scenery had "haunted him like a passion" – and Dorothy Wordsworth’s lyrical Journals. Wordsworth had made his home at Dove Cottage, in Grasmere, only a few miles from Langdale. Ruskin too had been haunted by this landscape from an early age: he had composed Iteriad, a verse travelogue on the Lakes, on a visit in 1830. He had a deep admiration for Wordsworth and his belief in nature’s role as educator, not forgetting his campaigns for the protection and preservation of the landscape. His first book Modern Painters was a homage not only to Turner, but to the Lakeland poet with a quotation from The Excursion as its motto.

In 1860, Gordon at Easthampstead had faced not dissimilar challenges to those that confronted Ruskin in 1871: dilapidated buildings and acres of land to cultivate and tame. Both men shared a mission – to improve people’s living conditions and the moral fabric of society. By the time of his visit to Brantwood, Gordon had twelve years’ practical experience of managing ninety-three acres of glebe, numerous staff, rebuilding a church and rectory. He was already a successful, much-respected farmer. Ruskin, on the other hand, lacked practical experience. He tended to indulge in schemes and projects that he was not able to sustain for any length of time; he called them experiments. He had many ideas, was extremely creative and had much enthusiasm.

Ruskin had a particular purpose in taking Gordon to Langdale, a quiet, unspoiled spot, untouched by industrialisation. The aim was to show him its system of waterworks and sluices, powerful cascades and forces that could be used to provide natural energy for the villagers. On the Brantwood estate, a "deep and steep water-course, a succession of cascades […] over hard slate rock" served as a laboratory for Ruskin’s geological observations concerning erosion and riverbeds. Clean, bacteria-free water was a most precious commodity and Ruskin gave considerable thought to a distribution system.

In Switzerland in 1869, harnessing the snow waters of the Alps for humanitarian purposes had been one of Ruskin's preoccupations. From Brieg, on 4 May 1869, he wrote of his concerns: “I have been forming some plans as I came up the valley from Martigny. I never saw it so miserable, and all might be cured if they would only make reservoirs for the snow waters and use them for agriculture, instead of letting them run down into the Rhone, and I think it is in my power to show this” (19.lv). Ruskin was also instrumental in a scheme to provide a fountain with fresh drinking water in the village of Fulking, in Sussex; similarly, Pritchard's fountain was equally important to the people of Broseley.

It was at Langdale also that Ruskin initiated his scheme for the spinning of linen and the development of what would be known as the Langdale Linen Industry, thus providing work for the villagers. Ruskin spent much of the following year (1873) at Brantwood, interspersed with lectures at Oxford.

Ruskin’s next continental tour took place between late March and the end of October 1874. Apart from the Alps, much of the time was spent in Italy, in Rome (where he worked for over two weeks in the Sistine Chapel copying Botticelli's Scenes from the Life of Moses), in Assisi (spending several weeks copying works by Giotto and Cimabue), in Florence, in Lucca (sketching the tomb of Ilaria di Caretto) and other places. At some point during the tour he was joined by Jane Pritchard, as her brother informed Ruskin: "My sister was much pleased at meeting you abroad. She did not return very well, and I think got a touch of fever which she has not quite shaken off" (Letter 11 June 1874, Lancaster. The paragraphs below quote from this letter five times.).

Architecture and preservation of buildings remained at the foremost of his mind. His refusal of the prestigious Royal Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) propelled Ruskin once again into the centre of controversy. From Rome, on 20 May, he wrote to the Secretary, Charles Eastlake, explaining the reasons for his refusal. A further exchange of correspondence ensued (34.513-16).

While in Italy, Ruskin received an invitation from Mr Chapman of the Glasgow Athenæum Lecture Committee to speak at one of their meetings during the winter. He declined. His letter of refusal (26 May 1874), although addressed privately to Mr Chapman, quickly became public and was published first in the Glasgow Herald of 5 June 1874, and reprinted in The Times of 6 June. Professor Ruskin's letters were much sought after and of such originality that they were guaranteed to increase newspaper sales. The question of copyright and confidentiality does not seem to have been considered. His refusal to speak in Glasgow was, he explained, not only due to an "increase in work" but to the types of audiences who attended soley for entertainment:

I find the desire of audiences to be audiences only becoming an entirely pestilent character of the age. Everyone wants to hear – nobody to read – nobody to think; to be excited for an hour – and, if possible, amused; to get the knowledge it has cost a man half his life to gather, first sweetened up to make it palatable, and then kneaded into the smallest possible pills – and to swallow it homoeopathically and be wise – this is the passionate desire and hope of the multitude of the day. [34.517]

Ruskin recommended: "A living comment quietly given to a class on a book they are earnestly reading – this kind of lecture is eternally necessary and wholesome" (34.517). But he denounced, intentionally in popular language, "your modern fire-worky smooth-downy-curry-and-strawberry-ice-and-milk-punch-altogether lecture [as] an entirely pestilent and abominable vanity" (34.517). He invoked Charles Dickens (1812-1870) whose continual round of speaking engagements and epic tours in America in 1867-1868 had contributed to his death and reminded readers of his demise: "the miserable death of poor Dickens, when he might have been writing blessed books till he was eighty, but for the pestiferous demand of the mob, is a very solemn warning to us all, if we would take it" (34.517).

Gordon read the letter, almost certainly in The Times, and was prompted to respond not only to Ruskin but also to Joan Severn. In his letter to "My dear Ruskin", he expressed his approval:

I wrote to her [Joan Severn] to say how glad I was that you had declined to waste your strength on public lecturing – All you say on that subject is perfectly true. People go simply (at least the mass of them) to be amused and many of them come across with the idea that they have done you a compliment by attending. It is perfectly monstrous to expect any man to waste his strength and shorten his life, for what not one in 100 is able to value, or cares for, one hour after the lecture is over! I believe too that lecturing has a bad effect on the performer himself. You will do well to confine your lecturing to workers and students who will value it [.] When I used to attend lectures, I used to find that I knew part before that I could not understand and then part – and that the residuary quantity did not always agree with me.

Ruskin shared this letter with Joan Severn, his "Darling Pussie", and he was highly amused by Gordon's own reaction to lectures. "The bit about the three parts of lectures is very funny", he wrote at the top of the letter.

Gordon kept Ruskin, then staying in a Sacristan's Cell in a Roman Catholic monastery in Assisi, informed about his private and social life. There had been a gap in their relationship. Gordon, seemingly not knowing that Ruskin was abroad, had gone to see him in Oxford but learned that he "had departed the day before". He was planning to go to Shropshire the following day, 12 June, to visit his sister Jane at her country mansion Stanmore Hall, near Bridgnorth. He also wrote about his invitation, two weeks before, to dine with "Mr Ritchie" at Highgate, in north London: it was his first visit and he was "quite charmed with the view". "The house", he continued, "is about on the level of the Cross of St Pauls". Henry Ritchie had been John James Ruskin's trusted clerk in his Billiter Street office.

On his return, Ruskin delivered a series of lectures in Oxford on science and geology, published later as part of Deucalion. He was working hard and feeling overwhelmed: "Greatly oppressed by impossibility of doing what I plan, and by failing strength" (Diaries, III, 837). But his personal life was far from happy, and on 28 May he received news he was dreading, but knew to be inevitable; Rose La Touche had died on 25 May 1875 at seven o'clock in the morning. He wrote to his Coniston friend Susan Beever: "I've just heard that my poor little Rose is gone where the hawthorn blossoms go" (Ruskin and Rose La Touche 133). In January 1875 he informed his readers in Letter 49 of Fors Clavigera: "The woman I hoped would have been my wife is dying" (28.246). If any letters were sent in response to this cri de cœur, they were not published by Cook and Wedderburn the editors so protective of Ruskin's private life. Ruskin saw Rose for the last time on 25 February 1875, and recalled, in a letter to the artist Francesca Alexander twelve years later, the poignant scene:

Of course she was out of her mind in the end; one evening in London she was raving violently till far into the night; they could not quiet her. At last they let me into her room. She was sitting up in bed; I got her to lie back on the pillow, and lay her head in my arms as I knelt beside it. They left us, and she asked me if she should say a hymn, and she said, "Jesus, lover of my soul" to the end, and then fell back tired and went to sleep. And I left her. [Hewison, Warrell, and Wildman, 261]

Ruskin's sketch of Rose on her deathbed encapsulates the wasted life of the young woman, her hysteria and the demise of his longed-for happiness with her.

In December 1875, Ruskin was invited to stay at Broadlands, near the town of Romsey, the spacious Hampshire home of his close and sympathetic friends Georgiana and William Cowper-Temple. They took spiritualism seriously and in the stillness of the winter countryside conducive to such activity – tapping and faint voices could be distinctly heard – organised regular séances. Several spiritualists had been invited as house-guests (Hilton, Later Years 325). Thus on 14 December, Ruskin learnt from a medium "the most overwhelming evidence of the other state of the world that has ever come to me" (Diaries, III, 876). In his extremely fragile state, he was predisposed to believe that Rose was communicating with him. (For Ruskin’s letter about this experience at Broadlands, see Landow: "'I heard of a delightful ghost'.)

Ruskin wrote to Gordon about his spiritual contact with Rose. Knowing his friend's mental anguish, Gordon was extremely supportive, sympathetic and understanding in his letter of 14 January 1876. His reply was pragmatic and kindly: "I feel sure that that Presence was permitted to make itself known on purpose to cheer and comfort you" (Lancaster). Gordon stressed that it was not a figment of the imagination since a complete stranger witnessed the vision: "If you only or even Mrs Temple who knew the hearts of both of you had been witnesses it might be supposed to have been fancy making [to?] itself a reality – but the evidence of a stranger staying in the house disposes of that presumption."

The apparition was meant to be beneficial, Gordon argued: "I am sure you think rightly that this was not designed for your evil but for your good – and you connect her visit with her prayers." Gordon gave Ruskin further consolation in stating his firm belief in the power of prayer in alleviating suffering and cited an example of its beneficial effect on one of his very sick friends:

I was asked two weeks since to offer the prayers of the Church for a dear friend – In answer I said that I certainly would for prayers might be answered in other ways besides miraculous healing – as e.g. by mitigation of pain or peace of mind and that happened in this case for the disease was of the most agonising kind, he had not a throb of pain; and his mind was in perfect peace and clearness till the very last, knowing everything and thinking of every-body[']s good.

Gordon concludes: "I am a firm believer in spirits and in prayer & in miracles – nor is my belief in the latter at all weakened because I have had no experience of them – I at present expect none – It is a great real power but at present in reserve."

*

Gordon was a recipient of Fors Clavigera, Ruskin's monthly public letters on a wide range of issues, often written in a rambling, sometimes incomprehensible manner. They were supposedly addressed to the workmen of England, sometimes more specifically the "Sheffield ironworkers" or "working men of Sheffield". Even Gordon did not read many of them: neither did his friends "except to find the mistakes" (28.637) . However, one of Ruskin's communications attracted his attention – Letter 64 ("The Three Sarcophagi") of April 1876. Just before leaving for Dublin, he found time to comment on this dogmatic letter that commences with a "Bible lesson" – an analysis of Genesis – and an exhortation to learn by heart the fifteenth chapter "with extreme care" (28.561). Ruskin acknowledged that he was not sure of his interpretation of Psalm 87, but suggested that, "as far as any significance exists in it to our present knowledge, it can only be of the power of the Nativity of Christ to save Rahab the harlot, Philisita the giant, Tyre the trader, and Ethiopia the slave" (28.562). It so happened that Psalm 87 was fresh in Gordon's mind as he had "expounded it in a sermon some time since, and was talking of it to a very learned Hebraist last Monday" (28.637). He wrote to correct Ruskin's error about the meaning of Rahab in the context of the Psalm: "Rahab, there, is generally understood to mean 'the monster', and has nothing to do, beyond resemblance of sound, with Rahab the harlot. And the monster is the crocodile, as typical of Egypt. In Psalm lxxxix (the Bible version, not the Prayer-Book), you will see Rahab explained in the margin, by 'or Egypt'" (28.637).

Gordon made a further suggestion: "Perhaps Rahab the harlot was called by the same name from the rapacity of her class, just as in Latin lupa" (28.637). The problem of interpretation was, Gordon believed, due to the bad translation that rendered it "unintelligible", but it remained nevertheless "charged with deep prophetical meaning" (28.637). In a footnote to his letter, Gordon added: "I hope you will have had a pleasant journey when you receive this. The Greek Septuagint is much better than the English, but not good. As regards the general meaning, you have divined it very correctly" (28.637). So in the June letter of Fors Clavigera, entitled "Miracle", Ruskin acknowledged Gordon's help, but without naming him, in rectifying an error in the April letter: "I've got a letter, not from a jackanapes, but a thoroughly learned and modest clergyman, and old friend, advising me of my mistake in April Fors, in supposing that Rahab, in the 89th Psalm, means the harlot. It is, he tells me, a Hebrew word for the Dragon adversary" (28.618).

Ruskin remained preoccupied with this Biblical interpretation (and many others) when in Venice the following year. The problem arose again when he was writing St. Mark's Rest. In chapter two, he returned to "Rahab" and linked the reference to the statue of St. Theodore, first patron of Venice, standing on a crocodile, representing his "Dragon-enemy – Egypt and her captivity", at the top of a pillar in the piazzetta. He publicly acknowledged his gratitude to "Mr. Gordon" and seemed to enjoy drawing attention to his own "curious mistake" (24.228).

During this long Venetian stay, Ruskin was welcomed by many friends, old and new. Rawdon Brown was there; so was Edward Cheney, who, since the death of his brother Robert Henry on 30 December 1866, was châtelain of Badger Hall. Ruskin was immensely indebted to Cheney for his learned publications – Remarks on the Illuminated Manuscripts of the Venetian Republic and his Original Documents Relating to Venetian Painters and their Pictures in the 16th Century. These works assisted Ruskin in the compilation of his Guide to the Principal Pictures in the Academy of Fine Arts at Venice, arranged for English Travellers, published in 1877. He acknowledges Cheney's "admirable account" of Titian's fresco of St Christopher over a door in the Ducal Palace (24.182). As a homage to Cheney, Ruskin reprinted, as an Appendix to his Guide, Cheney's text of the interrogation undergone by Veronese regarding his painting The Supper in the House of Simon. Ruskin introduced the Appendix with full recognition of Cheney:

The little collection of Documents relating to Venetian Painters already referred to [...], as made with excellent judgment by Mr. Edward Cheney, is, I regret to say, 'communicated' only to the author's friends, of whom I, being now one of long standing, emboldened also by repeated instances of help received from him, venture to trespass on the modest book so far as to reprint part of the translation which it gives of the questioning of Paul Veronese. [24.187]

Ruskin also drew on his Shropshire friend's publication for information about the legend of St Theodore that he used in St Mark's Rest (24.226).

Ruskin's departure for the continent coincided with Gordon's visit to Bridgnorth. The occasion was the unveiling of a memorial window – the great east window – in St Leonard’s Church to his former Headmaster Dr Thomas Rowley on the latter’s seventy-ninth birthday on 24 August 1876. St Leonard’s Church had been almost completely rebuilt in the 1860s, thanks to the initiative of the Rev. George Bellett (rector from 1835 to 1870) and generous sponsors among whom was John Pritchard. In particular, Pritchard funded the construction of the south aisle – formerly the chantry chapel of Our Lady – in memory of his brother George who had died in 1861. The architect was William Slater (1818/19-1872), a pupil and partner of the Gothic Revivalist Richard Cromwell Carpenter (1812-1855). This mainly Victorian, red sandstone edifice with its dominating tower was – and so remains in the twenty-first century – an impressive sight in the High Town. Clayton & Bell were chosen to design and make the memorial window: they had already worked in St Leonard’s in 1872 on windows in the south wall. This was a prestigious firm with many commissions throughout England, such as the large Minstrel window of 1874 in St Peter's Church, Bournemouth, nearly all the stained glass in Exeter College, Oxford, and much more. The theme chosen for the great east window in St Leonard's Church, Bridgnorth, was the Te Deum, with Christ seated in majesty with the four Evangelists and figures from the Old and New Testaments below.

Gordon was a guest of honour, and other students and acquaintances of Rowley were invited to this very special birthday event. How satisfying for Rowley to witness the success of two of his star pupils, the Rev. Osborne Gordon and the Rev. Dr James Fraser (1818-1885), Bishop of Manchester, who took a key role in the proceedings of the day. Fraser delivered an address in the Church and presided at a Public Luncheon in the Agricultural Hall at which Gordon proposed his health. Gordon's speech was described in the local paper, the Bridgnorth Journal, as "sparkling throughout with bright flashes of the liveliest wit and gayest humour". The praise continued: "his easily flowing, – almost gushing, – and gracefully refined eloquence, charming and really entrancing his audience; who testified their delight by no measured and oft repeated applause" (2 June 1883). The town of Bridgnorth was immensely proud of Gordon. On the occasion of the unveiling of the window it was stated that, with Gordon and other scholars, the "town could proudly boast of such an assemblage of literary, learned and scientific men as could not be surpassed by any town in the kingdom".

Within Fors, Letter 83 of October 1877, Ruskin quotes large sections from C. O. Müller's Dorians about capital punishment including a punishment that consists of "throwing the criminal into the Cæadas". In a footnote, Ruskin expresses his gratitude to Gordon for explaining the meaning: "I did not know myself what the Cæadas; so wrote to my dear old friend, Osborne Gordon, who tells me it was probably a chasm in the limestone rock; but his letter is so interesting that I keep it for Deucalion" (29.222). Ruskin does not seem to have used Gordon's letter.

It was in Fors of August 1877 that Ruskin gave a list of his tried and trusted friends "with their respective belongings of family circle". Gordon was among the chosen eleven! The "family" members were Henry Acland, George Richmond, John Simon, Charles Norton, William Kingsley, Rawdon Brown, Osborne Gordon, Burne-Jones, "Grannie" (Lady Mount-Temple), "Mammie" (Mrs Hilliard), and poet Jean Ingelow. His criterion was "those who will help me in what my heart is set on" (29.184). Ruskin was overwhelmed by work and sometimes annoyed by correspondents who wrote about what he considered to be trivia. A request from a chronophage to see him for five minutes and show him his little daughter sparked a reply about friendship.

Last modified 11 March 2020