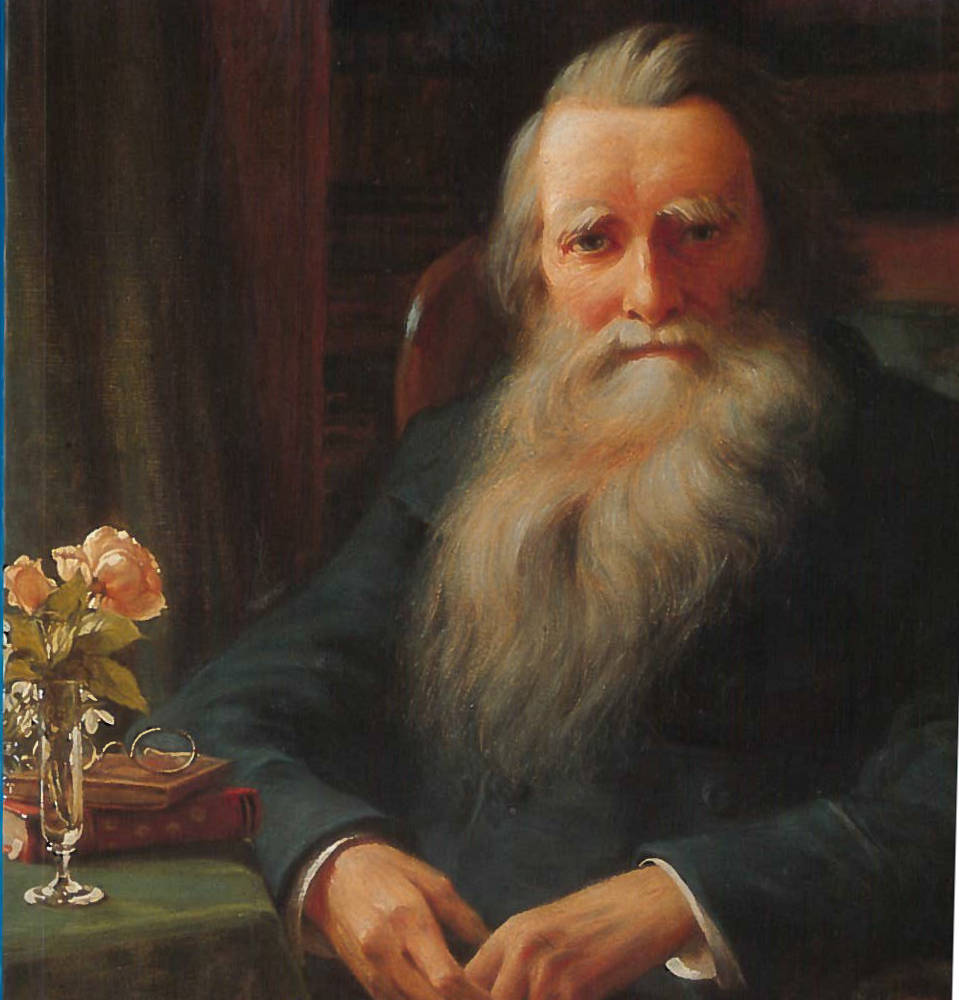

Osborne Gordon. Courtesy of Mr. Roger Pope. Click on image to enlarge it.

Gordon never married. He remained for twenty-three years as rector of the church of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene, Easthampstead, until his death, at the age of seventy, on Friday, 25 May 1883.

His last years were overshadowed and blighted by two unpleasant events that took their toll on him and from which he never seemed to recover. Like Ruskin, Gordon was a devoted, loyal and caring employer. In the autumn of 1878, the following three members of the domestic staff, seemingly residential, were employed at Easthampstead Rectory – housekeeper Mrs Fanny Worrall, a servant named Fanny Elizabeth Hayward, and a fourteen-year-old page boy named Frederick William Pee, born in June 1864 at Shineton (also written Shinton), Shropshire.

Frederick Pee was the son of William Pee, a coachman at Aston Hall, near Newport, Shropshire, and of Eliza, née Sewell. Frederick had been employed by Gordon as a general waiting boy since 23 March 1878, for just over six months when he committed suicide at Easthampstead Rectory. An inquest was held on Wednesday 2 October 1878 at which details of the events were unveiled and which Reading Mercury for 5 October 1878 reported the statements of the three chief witnesses. There had been several instances of Frederick's unsatisfactory conduct. On Monday 30 September, soon after 6 o’clock, housekeeper Mrs Worrall asked Osborne Gordon to speak, yet again, to Frederick on account of his disobedience. Gordon, the principal witness at the inquest on Wednesday 2 October, related to the coroner, Mr. W. Weedon, the sequence of events:

I talked to him as I had many times before, and told him we must part. He left the room abruptly, and about five minutes afterwards Mrs. Worrall came to me and said deceased had wished Fanny, the maid, goodbye, and had gone upstairs, and that she was afraid to follow him. I soon afterwards heard a report and went up to deceased’s room. I found the deceased under the bed, and on examination found his brains blown out. Looking at the whole of his conduct while he had been with me, I feel sure he was not in his right mind; he was very silent, and his disobedience was of the most extraordinary kind. I did not look for a pistol, but understood afterwards that the policemen found one in the room. No one was in deceased’s room when I went there. I did not know that the deceased had a pistol.

Further vivid, first-hand evidence was given by Fanny Elizabeth Hayward:

I always thought him [the deceased] very strange. He was not very cheerful at times. About 6.30 on Monday evening last, I saw him cross the passage to go upstairs; he took my hand and said "Good-bye Fanny". I said, "Oh Frederick, what are you going to do?" He made no reply, but rushed upstairs. I went to Mrs. Worrall at once. We went to Mr. Gordon, but before getting to his door we heard a report like that of a pistol. The report seemed to come from deceased’s room. I was sent to fetch someone. I have seen a pistol in deceased’s room. He told me he bought it in Wokingham, about two months back, to shoot birds with. He had used it for that purpose. When first deceased came he complained of headache. Sometimes he sulked and would not come in to meals. He did not complain of anyone or anything beyond his head. The household consisted of Mr. Gordon, the housekeeper, myself, and the boy.

The testimony of police constable Molsher followed:

About 7 p.m. on Monday, I was sent for to the Rectory. I went to the deceased’s bedroom, and found his body on the floor, and blood and brains about. At his feet I found the pistol produced, and in the window two small bottles, one of powder, the other of shot. [Reading Mercury, 5 October 1878]

Osborne Gordon had particularly requested the opinion of Mr. Thomas Croft, the surgeon, who reported on the health of the boy: "In April last I was visiting here and the rain detained me. I then tried to get into conversation with deceased, but could not. I noticed what a peculiar boy he was, and from what I observed I thought him liable to sudden impulses."

The jury returned a verdict that "Deceased committed suicide by shooting himself during a fit of temporary insanity".

Marshall relates in a direct and personal way the effect upon Gordon:

The poor lad left his master’s presence, wished his fellow-servants a hurried good-bye, rushed to his own room and shot himself. To Mr. Gordon, the most tender-hearted and considerate of men to all about him, this was a frightful blow from which it is probable he never quite recovered. He did not sleep for three nights; he shrunk from observation: and when he was prevailed upon to keep a long-standing engagement at Milton, was on his arrival utterly prostrate. It was plain that his whole system had received a violent shock. [57-58]

It would not have escaped Gordon’s memory that this was the second death to occur at his rectory. On 29 October 1865, George Palmer, a neighbour of Gordon’s younger brother, Alexander, who farmed at The Hills, in Chetton, Shropshire, died at Easthampstead Rectory. Palmer is buried in a tomb to the right of the south entrance to Easthampstead church.

The second harrowing event in the same year as Frederick Pee's suicide was the unresolved death of Gordon’s neighbour and friend, Sir William Hayter, retired Judge Advocate General, at his large estate of South Hill Park. Late morning, on Boxing Day, Thursday 26 December 1878, a hat was seen floating on one of the icy lakes at South Hill Park. "That's my dear master", exclaimed James Dougal, the steward, as he arrived on the scene. He grabbed a rake and immediately jumped into the water. With the help of John Ayres the butler and other members of staff who had been searching for Sir William since his disappearance earlier in the day, he dragged the cold body out of the water. There was no sign of life and no sign of any struggling near to where the body was found.

An inquest was held on Saturday afternoon, 28 December 1878, chaired by the Reading coroner Mr W. Weedon. Gordon was one of thirteen jurymen who listened to evidence from witnesses including Sir William's steward and butler. Dr Orange, medical superintendent of Broadmoor Asylum, who had known the deceased for the last fifteen years, and who examined the body externally, had no doubt that death was due to drowning, perhaps after an attack of dizziness. On Monday, 30 December 1878, The Times reported that the evidence was inconclusive as it was also reported that Sir William had been prone to depression. In summing up, the coroner indicated to the jury that "it might have been an accident and might have been suicide", adding that "to return an open verdict of 'Found drowned' would meet the case" (6). After a short deliberation, that was the verdict of the jury.

For such a sensitive person as Gordon, hearing the harrowing evidence relating to the unexplained loss of a friend, neighbour, Churchwarden and benefactor would have been painful. The whole affair was a shock, for church teaching was against suicide. Gordon conducted the funeral and laid Sir William to rest in Easthampstead churchyard on 2 January 1879; he was in his eighty-seventh year. In a sermon preached later that month, Gordon generously, affectionately and with delicacy paid tribute to Sir William:

Of him of whom I am about to speak my words will not be many. I miss, and you will long miss with me, that venerable face which I have seen turned towards me with attentive ear for so many years in this pulpit. […] He was as free, open-hearted, and generously-minded as a high-born boy, who has not yet learned that there is such a thing as selfishness or imposture in the world. […] He was incapable of a base or sordid insinuation to account for conduct that was not base or sordid. […] There are those here who know that he would not only do a kindness, but how he would labour and persevere in doing it, at the expense of great trouble and personal exertion, even in his extreme of old age and, declining health. And his attachment to the church, which would not have been built as it is, if it had not been for him, and of which he was proud to be Churchwarden, is well known to you. […]

It has not pleased Providence that this grand and good old man should be taken from us (peacefully in his bed). It pleased God in His inscrutable wisdom – for I doubt not His wisdom – to prolong his days till that calm, equitable, and true-judging, practical mind was off its balance, and he became haunted by the idea of imaginary evils which pressed upon his brain. We simply know the fact of his end and the mode of it. It may have been a pure accident […]. I committed his honoured remains to the earth with the same confidence in the mercy of Almighty God, with the same trust in the saving virtue of the blood of Jesus Christ, with the same sure and certain hope of a resurrection to eternal life as if instead of dying alone, in the cold water, and under the chill covering of a wintry sky, he had died calmly in his bed, surrounded by all that were dear to him to catch his dying breath and with the words of humble resignation or ather triumphant hope, upon his lips, "Lord now lettest Thou Thy servant depart in peace" [Marshall 327-33].

Outwardly Gordon continued to exercise his functions and enjoy his work and social life and to preach. On Saturday 17 June 1882, he was a guest at the annual speech day at Wellington College, along with Royal visitors, the Prince and Princess of Wales (the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, was President of Wellington College). Gordon lunched with Ruskin at Herne Hill on 20 December 1882, shortly after the latter's return from a long continental journey. His diary entry is brief: "Thursday 21 Dec 82 [...] Y[esterday] Gordon at lunch" ("Diary of John Ruskin August 1882-January 1883", ref. Ms 23, folio 135 right hand page, Lancaster). After partially recovering from illness, the now bearded, sixty-three-year-old Ruskin had spent late summer, autumn and early winter of 1882 in France (mainly Burgundy), Switzerland and Italy, accompanied by W. G. Collingwood (Gamble and Pinette). Ruskin had subjected himself to a gruelling schedule abroad and, unable to relax and engaged in a permanent battle against time, suffered increasingly from depression and mental instability.

Marshall’s last sight of Osborne Gordon

Marshall recalls with emotion the last time he saw Gordon:

The last time that the writer saw Mr. Gordon in his own home was in December, 1882, when, in company with the learned and accomplished Master of Wellington College [Rev. Edward C. Wickham], he went over to Easthampstead one dismal afternoon to see him. There had been a fall of snow, several inches deep, overnight, but at some distance from his house, near the church, they met Mr. Gordon on his way to the school. He looked, as they thought, worn and aged, but turned back with his visitors, and welcoming them with his wonted cordiality and cheerfulness, entertained them with a packet of correspondence just received from Town, in a tone that quite dispelled any misgivings on the score of health in the writer’s mind. He is afraid that he sunk several degrees in his companion’s estimation by his unrestrained amusement at Mr. Gordon’s humourous comments. [58]

Although in failing health, Gordon nevertheless preached what would be his last sermon on Trinity Sunday, 20 May 1883, only five days before his death. The subject, "Trinity in Unity", was a clear and long statement of Gordon’s strong Christian beliefs, and is reproduced in full in Marshall’s Memoir [338-49].

Farewell to "Ozziegogs"

Ruskin in the 1880s and '90s: Ruskin by W. Roffe (at left) and W. G. Collingwood.

At the time of Gordon’s death, Ruskin was nearby in Oxford. He had been re-elected as Slade Professor of Fine Art in January 1883 and was heavily involved in the preparation and delivery of a series of lectures on English art. On Wednesday 16 May, the day of his lecture announced in the University Gazette as "Mythic Schools (Burne-Jones and G. F. Watts)" (33.287-305), Ruskin had enjoyed the company of Gordon (whom he called affectionately "Ozziegogs") and his sister Jane, and had reported positively about Gordon's health and happiness. He shared his joy with Joan Severn in a letter the following week on 23 May 1883:

It has been hot to day – but I've got a lot of work done, and a pleasant evening walk. I never told you that on the day I came up to lecture, and returned – Wednesday last week, I met Osborne Gordon and Jane at Reading and got them into my carriage to Oxford. Ozziegogs looking so well and both so glad to see me! [ref. L45, Lancaster.]

Only a few days later, Ruskin learnt of Gordon's death from Jane Pritchard but he delayed informing Joan Severn until the day of the funeral (30 May). He was writing from Oxford, where, on that very afternoon, he had to give another public lecture announced as "Fairy Land (Mrs Allingham and Kate Greenaway)" (33.327-49). Although Ruskin had an unmitigated horror of burials and disliked mourning and the wearing of black, on this occasion he had a valid reason for not attending Gordon's funeral. His thoughts were with Gordon, and he preferred to grieve inwardly and silently in a very personal way for his dear friend, as he explained to Joan Severn in a letter of 30 May 1883:

I was extremely grieved this morning to hear of Mr Allen's death: – Mrs Pritchard told me of Gordon's on the day he died, but I had no heart to tell you in your zest of happy excitement.

I am thankful to have had strength spared to me to complete at all events one course of lectures rightly, it does not seem to have tired me at all – and I hope that I may still be useful and active as Gordon was, to the last.

I wrote a line to Mrs Pritchard at once – and shall take notice of Osborne in a quiet but I hope – just and loving way, the next time I have to speak in Oxford. [ref. L45, Lancaster]

The funeral, conducted by Dean Liddell of Christ Church, took place on Wednesday afternoon, in Gordon's own church. Many friends, relations and dignitaries attended, including Lord Arthur Hill, 6th Marquis of Downshire, Sir Arthur Hayter MP of South Hill Park, Easthampstead (the son the late Sir William), Colonel Peel, John Walter MP for Berkshire, John Pritchard, William Pritchard Gordon and Alexander Gordon.

Gordon was buried in his own churchyard. His grave is marked by a standing tombstone of granite with a Celtic cross at the top. It was sculpted by Marylebone resident James Forsyth (1826-1910) and bears the following inscription with a biblical quotation from Hebrews XI:4:

TO THE LOVED MEMORY OF

THE REV. OSBORNE GORDON

FOR 23 YEARS RECTOR OF THIS

PARISH WHO DIED MAY 25 1883

"HE BEING DEAD YET SPEAKETH"

At the base on the right hand side is the name of the sculptor:

FORSYTH Sc

BAKER STREET

LONDON

A funeral sermon was preached in Easthampstead Church on Sunday 3 June by Gordon’s friend and former pupil, the Rev. Robert Godfrey Faussett (1827-1908). Faussett was laudatory about his old teacher:

I see a man of so happy and genial a nature, that he was ever the welcomest of the welcome in the society – even of the youngest, towards whom indeed his own fresh sympathies seemed in an especial manner to attract him: but who, while he could laugh unreservedly with the merriest lad among them, never tolerated an excess, or a profanity, in deed or in word.

I see a man who, apart from his powers of conversation and vast range of knowledge of men and things, possessed so keen a sense of humour, so sparkling and ready a wit, that his presence in his "common-room", or at the table of his co-evals, was always the centre and life of the party, but who was never known to utter an ill-natured word, nor do I think he ever harboured an unkind thought. [Marshall 60-61]

Gordon was greatly respected as a priest and farmer – his pigs were renowned. He delighted in country life and in observing the habits and peculiarities of the animal kingdom, particularly any displays of "high courage" (Marshall 67). Faussett reminisced: "He had a favourite black mare, whose vicious tricks were a source of absolute delight to him, though he was totally devoid of any conceit as to being able to ride her" (67). Former Christ Church scholar, tutor and Censor George William Kitchin (1827-1912) recalled that at his funeral one of his Berkshire farmers said: "Well, we have lost a real friend; we've had before parsons who could preach, and parsons who could varm; but ne'er a one before who could both preach and varm as Mr Gordon did" (Kitchin 24).

Obituaries to Gordon were published in The Times of 29 May 1883, and in the Telegraph. The Times of 29 May praised in particular his character, his achievements, and the high regard in which he was held:

Among his Christ Church pupils were many men distinguished in after life – Lord Salisbury, Lord Harrowby, Sir Michael Hicks-Beach, Mr. Ward Hunt, Mr. Ruskin. To have distinguished pupils is an accident, but to possess their esteem bespeaks merit. He had, however, one failing, if failing it was, to which the very brilliancy and facility of his powers contributed. He was of a temper essentially averse to exertion. He did, and did admirably, whatever he was called upon to do. But he did it without effort, and the exertion involved in what is considered a successful career would have been repugnant to him. In spite of certain eccentricities, which perhaps grew upon him in later life, as was becoming to a college don, he might have commanded success in any career. But he preferred to exercise over his little world an easy and good-natured d[e]spotism, tempered with his own epigrams, and to be the soul of common-room life, with its genial humours and local witticisms. Had he been a more ambitious man he might easily have climbed, for he was a sound and moderate Churchman, troubling himself, we believe, less with dogma than with practice, and a Tory of the deepest hue. He was one of those most valuable men who can write books but do not; who are universally accounted by those who know them capable of the greatest things, but are content with the place in which they find themselves, the work which they perform without trouble, and the career which is its own reward. The College living which Mr. Gordon held for more than 20 years is an illustration of the versatility of his abilities, where he showed that the career of a college don is compatible with being an esteemed parish priest, a vigorous church restorer, and a welcome neighbour.

Tributes were paid to him in the Telegraph: "Remarkable for his witty and incisive conversation, Mr. Gordon leaves a gap in the circle of those who knew him best which is little likely to be filled. […] His loss will be lamented far and wide, and by none more than his old and intimate friend, Mr. John Ruskin." His native Shropshire did not forget the local lad, and an obituary published in the Bridgnorth Journal on 2 June 1883 proudly extolled his academic accomplishments:

By his death the nation has lost one who added lustre to the blaze of learned fame surrounding Oxford University, as one of her most brilliant scholars. […] In his school days he was surrounded by and closely allied with a phalanx of ripe scholars, – young men of the highest attainments and ability, who in the ranks of learned men and in public life achieved the highest honours and distinction.

The Rev. Edward Whinyates expressed a high opinion of Gordon: "During the eighteen years we were together I never saw him once out of temper, and never heard him say a harsh unkind thing of man, woman, or child. […] He lived but to do good, and had especial influence over the young in his parish" (Marshall 65).

According to the DNB, citing the Calenders of the Grants of Probate and Letters of Administration , Gordon's wealth at his death was recorded as £25.572. 11s. 0d; probate was granted on 7 August 1883. He bequeathed all his possessions to his younger brother, Alexander John, who was residing at The Hill, near Bridgnorth, Shropshire. Gordon's goods included "farming goods and livestock including named horses and a black retriever dog and kennel, and [...] books in the library (mostly classical and religious works, including an 88-volume 'library of Anglo Catholic Theology', the works of John Ruskin and Alice in Wonderland)" (Ref. D/EZ118/2, Berkshire Record Office.). The total value was £1772, 12s. 6d. Alexander John did not live long enough to enjoy his inheritance and died intestate, a month later on 28 June, aged seventy-one, after being thrown from his carriage. His death was reported in The Times of Tuesday, 3 July, 1883: "On the 28th June, Alexander John Gordon, of The Hill, near Bridgnorth." The land that Gordon had owned at Priestwood Common, near Bracknell, subsequently passed to Alexander John’s son, Alexander. In his will, Gordon also left £100 for children who were members of the choir of the Parish of Easthampstead (Collins 92). Gordon's successor was the Rev. Herbert Salwey, a former Christ Church scholar who also hailed from Shropshire.

A two-day sale of the household furniture and effects and farming stock that had belonged to Osborne Gordon was held on 18 and 19 July 1883. (I am grateful to Ian Gordon for a copy of the sale catalogue with annotations by an unknown hand.) There were 439 lots. The sale on the first day raised £260.19.10 (two hundred and sixty pounds, nineteen shillings and ten pence): on the second day it raised £244.10.9 (two hundred and forty-four pounds, ten shillings and nine pence). The total sum raised is the equivalent of approximately £60,000 (sixty thousand pounds) in 2020 according the Bank of England’s inflation calculator. This figure must be considered with circumspection for some of the items would be considered to be extremely valuable by antique dealers and collectors today, whereas others would have little value. How can one value Gordon’s 8-day clock in a black marble case, by Henry Marc, Paris (lot 159), that sold for 10 shillings? Or a model of old Easthampstead Church under a glass shade (lot 126) that sold for 13 shillings? Or a pig killing stool (lot 297) that sold for 8 shillings? Or a "capital 4-wheel Phaeton by Newson" of Bond Street, complete with cushions, lamps etc (lot 350), that fetched £14? The most expensive item at the sale was a "Rick of Nursery Wheat, and about 2 loads of Barley on top" (lot 422) that fetched £46.

Last modified 14 March 2020