"Them Confugion steamers," said Mrs. Gamp, shaking her umbrella again, "has done more to throw us out of our reg'lar work and bring ewents on at times when nobody counted on 'em (especially them screeching railroad ones), than all the other frights that ever was took. I have heerd of one young man, a guard upon a railway, only three years opened — well does Mrs. Harris know him, which indeed he is her own relation by her sister's marriage with a master sawyer — as is godfather at this present time to six-and-tuenty blessed little strangers, equally unexpected, and all on 'um named after the Ingeins as was the cause. Ugb!" said Mrs. Gamp, resuming her apostrophe, "one might easy know you was a man's invention, from your disregardlessness of the weakness of our naturs, so one might, you brute!" [Martin Chuzzlewit, chapter 40]

"Oh, you're a broth of a boy, ain't you?" returned Miss Mowcher, shaking her head violently. "I said, what a set of hummbugs we were in general, and I showed you the scraps of the prince's nails to prove it. The Prince's nails do more for me in private families of the genteel sort than all my talents put together. I always carry em about; they re the best introduction. If Miss Mowcher cuts the prince's nails, she must be all right. I give 'em away to the young ladies. They put 'em in albums, [31-32] I believe. Ha! ha! ha! Upon my life, 'the whole social system' (as the men call it when they make speeches in Parliament) is a system of Prince's nails!" David Copperfield

It does not seem to me to be enough to say of any description that it is the exact truth. The exact truth must be there; but tbe merit or art in the narrator, is the manner of stating the truth. As to which thing in literature, it always seems to me that there is a world to be done. And in these times, when the tendency is to be frightfully literal and catalogue-like — to make the thing, in short, a sort of sum in reduction that any miserable creature can do in that way — I have an idea (really founded on the love of what I profess), that the very holding of popular literature through a kind of popular dark age, may depend on such fanciful treatment. [John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens, Book Nine, Chapter I]

s his eventful career bears witness, Dickens was very much

a man of his times; and it is in the full context of an age

primarily characterized by rapid change that his writings must, in the first

instance, be read if they are to yield their full meaning. Equally partial

and therefore reductive are the views of Chesterton and the Pickwickians, who find

the best of Dickens in the overflowing vitality of the

early novels with their nostalgic looking back to an

older order, and the views of writers like Gissing and

Shaw, who prefer the later works for their somberly

realistic portrayal of the new industrial society. The

very grounds for disagreement between the two approaches suggest the importance

of establishing a firm historical basis for the criticism of Dickens' achievement.

s his eventful career bears witness, Dickens was very much

a man of his times; and it is in the full context of an age

primarily characterized by rapid change that his writings must, in the first

instance, be read if they are to yield their full meaning. Equally partial

and therefore reductive are the views of Chesterton and the Pickwickians, who find

the best of Dickens in the overflowing vitality of the

early novels with their nostalgic looking back to an

older order, and the views of writers like Gissing and

Shaw, who prefer the later works for their somberly

realistic portrayal of the new industrial society. The

very grounds for disagreement between the two approaches suggest the importance

of establishing a firm historical basis for the criticism of Dickens' achievement.

In their exuberant and heterogeneous inclusiveness, Pickwick Papers, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, and Martin Chuzzlewit are unmistakably the work of the same inspired reporter who wrote Sketches by Boz. Dickens might have been offering his own apology for these early literary excursions when he had Pickwick say at the end of his pilgrimage: [33/34]

I shall never regret having devoted the greater part of two years to mixing with different varieties and shades of human character: frivolous as my pursuit of novelty may have appeared to many.... If I have done but little good, I trust I have done less harm, and that none of my adventures will be other than a source of amusing and pleasant recollection.

The guise in which The Uncommercial Traveller came before the public in 1860 shows that late in his career the writer still held to the aims with which he had set out:

Figuratively speaking, I travel for the great house of Human Interest Brothers, and have rather a large connection in the fancy goods way. Literally speaking, I am always wandering here and there from my rooms in Covent-garden, London — now about the city streets: now, about the country by-roads — seeing many little things and some great things, which, because they interest me, I think may interest others.

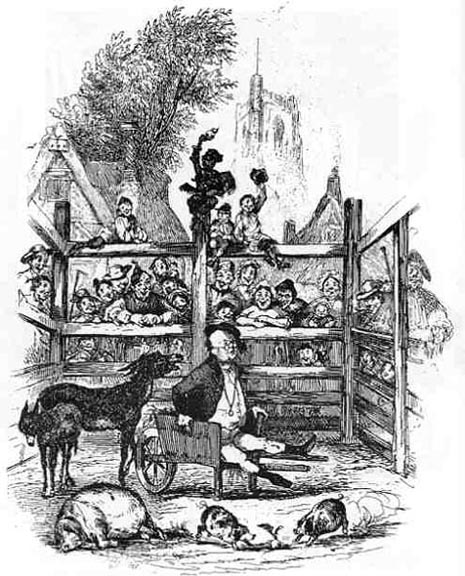

If Dickens' initial adoption of the picaresque mode was primarily determined by his boyhood reading of Cervantes and Smollett and Fielding, he could hardly have made a choice better suited to his purposes and talents. This form has been called the novel of successive encounters; and surely the great unrelated scenes of comedy and melodrama are the passages from Dickens' early stories which remain memorable. That, indeed, he constructed his narratives to link these scenes is apparent from the accompanying illustrations, the subjects of which were customarily specified by the writer. Examples crowd to mind: Pickwick in the Pound, the death of Sikes, the breaking up of Dotheboys Hall, Dick Swiveller teaching cribbage to the Marchioness, Sarah Gamp and Betsey Prig over tea.

Left to right: (a) Pickwick

in the Pound. (b) The breaking up of Dotheboys Hall. (c) Mrs. Gamp

Propoges a Toast. [Not in print version.]

Not surprisingly Dickens was to find that the material [34/35] most readily adaptable for public reading came from the earlier works. When, on the other hand, he wanted to carve out a section from David Copperfield, he ran into problems which he described to Forster as follows: "There is still the huge difficulty that I constructed the whole with intense pains and have so woven it up and blended it together, that I cannot yet so separate the parts as to tell the story of David's life with Dora." It has not been sufficiently remarked that the episodic nature of the picaresque tale was ideally suited as well for displaying the eccentricities in speech and behaviour of the comic and grotesque characters who constitute the indisputable triumphs of Dickens' art at this period. Sam Weller or Quilp or Mrs. Gamp or Pecksniff enjoy absolutely free and autonomous existences; to cramp any one within the exigencies of a tightly woven plot would be to deprive him of the opportunities for uninhibited self-expression which are the very principle of his being.

The reader who uncritically abandons himself to the panoramic vagaries of Dickens' first novels will hardly be disposed to linger over the occasional passages of social comment, incisive as these often are. The reforming conscience is present, but still diffused, principally concerned, as Shaw said, with "individual delinquencies, local plague-spots, negligent authorities." Real injustice and oppression occur within a framework of melodramatically contrived incidents. The victims suffer under private rancor which, as in the case of Monks' persecution of Oliver or Ralph Nickleby's of Kate, is preposterously motivated. The evil-doing of the villains is countered by the equally gratuitous benevolence of such characters as Brownlow, the Cheeryble brothers, and Garland. The distance which Dickens had yet to travel to achieve the sustained satire of his final period can be gauged by [35/36] contrasting the sporadic incursion of social criticism into his early novels with the full development of the same themes later on. Thus, Pickwick's brief incarceration in the Fleet looks forward to the Marshalsea setting which dominates so much of the action in Little Dorrit. Both Nicholas Nickleby and Hard Times take off from schoolroom scenes; but Squeers' brutal regime at Dotheboys Hall lacks the thematic relevance of Gradgrind's Benthamite institution. The horrors of the industrial landscape to which Nell is fleetingly exposed are little more than a preliminary sketch for the spiritual wasteland of Coketown in Hard Times.

Evil always darkens the world of Dickens' fiction; but the novelist was at the outset of his career more occupied with its effects than its causes. Suffering is visited on characters who are both defenseless and blameless, and whose plight, therefore, elicits a primarily emotional response. The forlorn child protagonists of Oliver Twist and The Old Curiosity Shop, and the idiot Barnaby Rudge sound depths of pathos better calculated to stir the sympathies than to awaken the critical intelligence.

Not before the mid-1840s did Dickens begin to view society in its organic wholeness, and so to perceive the importance of grouping individual lives within encompassing cultural patterns. This was a decade of extreme political and economic unrest, when the populace first felt the full oppression of the Industrial Revolution. Barnaby Rudge is the first of Dickens' novels to evince a consistent awareness of contemporary problems. The widespread apprehension aroused by the Chartist agitation for parliamentary reform is mirrored in the treatment of the mob scenes, even though these ostensibly describe the Gordon Riots of 1780. The American episodes in Martin Chuzzlewit [36/37] further illustrate Dickens' growing recognition of the power of society over its individual members. Those would-be individualists, Colonel Diver, Jefferson Brick, LaFayette Kettle, General Cyrus Choke, the Hon. Elijah Pogram, and Hannibal Chollop share a common identity in their blatantly nationalistic prejudices.

With Dombey and Son the dynamic operation of change on the life of the age begins to dominate Dickens' imagination. In the railways, spreading their network from city to city across the face of England, the novelist found an emblem for the innovating spirit which had overnight replaced the leisurely world of stagecoaches and country inns celebrated in Pickwick Papers. Although too lengthy for quotation, the description of Todgers's immemorial disorderliness in Chapter 9 of Martin Chuzzlewit should be compared with the description in Chapter 6 of Dombey and Son of the very different kind of disorder visited on Staggs's Gardens by the coming of the railroad. In Todgers's the past is inviolably preserved in the present; the scene from the ensuing novel asserts that today is only prelude to tomorrow. Equally suggestive is the contrast between the great commercial firm of which Dombey is the head and those piratical ventures belonging to a precapitalist era of which Dickens makes sport in Nicholas Nickleby and Martin Chuzzlewit under the ludicrous appellations of the United Metropolitan Improved Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and Punctual Delivery Company, and the Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Assurance Company

Both Ralph Nickleby and Montague Tigg are entrepreneurs, and, as such, assignable to no fixed social station. Dombey, on the other hand, is a pillar of middle-class respectability, and his inordinate pride is [37/38] inseparable from his social position. Along with its emphasis on change, then, Dombey and Son shows Dickens' growing into the class structure of Victorian society. To such characters as Pickwick and the Cheeryble brothers, material possessions imply no privilege beyond the opportunity to dispense charity, and they treat their beneficiaries as equals. Dombey is the progenitor of a long line of figures in later novels for whom wealth has become the symbol of status, conferring the right to oppress the less fortunate. Variations on the type are Bounderby, Merdle, and Podsnap. William Dorrit joins this company when he inherits his fortune and is able to translate into actuality his playacting in the role of Father of the Marshalsea. Boffin and his wife are Dickens' agents for ridiculing respectively the snobbish aspiration for culture and the love of fashionable display which accompany newly gained riches. Altogether more biting in its reflection on Podsnappery, however, is the miserly pretense which the Golden Dustman assumes to bring Bella Wilfer to her senses. An article from Blackwood's Magazine for 1855, quoted by Humphry House, perceptively attributes the novelist's success to his understanding of the capitalist mentality, but seems curiously obtuse in suggesting that Dickens was temperamentally sympathetic with that habit of mind:

We cannot but express our conviction that it is to the fact that he represents a class that he owes his speedy elevation to the top of the wave of popular favour. He is a man of very liberal sentiments — an assailer of constituted wrongs and authorities — one of the advocates in the plea of Poor versus Rich, to the progress of which he has lent no small aid in his day. But he is, notwithstanding, perhaps more distinctly than any other author of the time, a class writer, the historian and representative of one circle in the many ranks of our social scale. Despite their descents into the lowest class, and their occasional flights into the less familiar [38/39] ground of fashion, it is the air and breath of middle- class respectability which fills the books of Mr. Dickens.

In the novels written during the 1850s Dickens came increasingly to associate everything he found amiss in the world about him with the concentration of power in the moneyed middle class. Institutions which had traditionally existed to safeguard the general welfare seemed to him to have passed into the hands of vested interests, committed to perpetuating rather than reforming existing evils. Beginning with Bleak House, the writer set out to strip away the hypocritical facades masking the abuse of authority in high places. His blanket term for the monopoly of power by privileged groups was the "System." In a moment of lucidity Gridley, the litigant from Shropshire, makes the following despairing comment on the toils of Chancery which have enmeshed him:

The system! I am told, on all hands, it's the system. I mustn't look to individuals. It's the system. I mustn't go into Court, and say, "My Lord, I beg to know this from you — is this right or wrong? Have you the face to tell me I have received justice, and therefore am dismissed?" My Lord knows nothing of it. He sits there, to administer the system.... I will accuse the individual workers of that system against me, face to face, before the great eternal bar!

Society in its institutionalized aspect has replaced the individual malefactors of the earlier novels as the true villain.

Dickens' scorn for the governing class dated from his days as a journalist, when he reported the parliamentary debates leading up to the passage of the Reform Bill of 1832. During the subsequent decades his pessimism was accentuated by a variety of factors: the ineptitude of legislative attempts to deal with the [39/40] distress brought on by the Industrial Revolution, the disillusionment of his tour in America, the influence of Carlyle's antidemocratic writings. In 1854 the novelist was proclaiming his "hope to have every man in England feel something of the contempt for the House of Commons that I have." And the following year after the Crimean debacle he stated:

I am hourly strengthened in my old belief that our political aristocracy and our tuft-hunting are the death of England. In all this business I don't see a gleam of hope. As to the popular spirit, it has come to be so entirely separated from the Parliament and Government, and so perfectly apathetic about them both, that I seriously think it a most portentous sign.

This attitude dictated the brilliant parody of party faction in Bleak House, with its portrayal of the "'oodle-ites" and the "'uffy-ites" maneuvering for the spoils of office. Broader based and more searching in its implications is the mockery in Little Dorrit of the Circumlocution Office under the domination of Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle and his parasitic clan. Dickens' political satire culminates in the chapter in Our Mutual Friend describing how the upstart Veneering bribes his way into Parliament with the wealth derived from wildcat speculation in corporation shares.

Early experience had left Dickens with as little respect for the legal profession as for politicians. With rare exceptions, such as Jaggers in Great Expectations, the attorneys in his novels discredit their calling. They are the venal and frequently fraudulent supporters of the established order, masters of prevarication and double-dealing. The "Wiglomeration" against which John Jarndyce rails is their natural element. Many of Dickens' most memorable scenes from Pickwick Papers to A Tale of Two Cities take place in courtrooms [40/41] and make fun of legal procedures. Bleak House, however, contains Dickens' most concentrated attack on this form of institutionalized chicanery. The lineaments of Tulkinghorns Vholes, Conversation Kenge, and Guppy are carefully differentiated, but all make their living off Chancery and have a common interest in preserving that outworn relic. The blighting effect of the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce on the lives of its innocent victims is conveyed in the catalogue of names for Miss Flite's birds, which swells to a crescendo of wild humor: "Hope, Joy, Youth, Peace, Rest, Life, Dust, Ashes, Waste, Want, Ruin, Despair, Madness, Death, Cunning, Folly, Words, Wigs, Rags, Sheepskin, Plunder, Precedent, Jargon, Gammon, and Spinach."

In the world of Dickens' novels the irresponsibility of religious bodies matches that of the law. The nonconforming sects in particular aroused the writer's animus, and he took savage delight in pillorying such canting hypocrites as Stiggins, the Reverend Melchisedech Howler, and Chadband. Although always ready to enrol his name in support of legitimate causes, Dickens recognized that too often organized philanthropy was only incidentally occupied with its professed goals. The fashionable sponsorship of charitable enterprises calls forth from Boffin a memorable tirade; and the type of professional "do-gooder" is scathingly anatomized in Bleak House. The rapaciously benevolent Mrs. Pardiggle, forcing her Puseyite tracts on the bricklayer and his family, is as little mindful of their true needs as Mrs. Jellyby, immersed in schemes for the colonization of Borioboola-Gha, is attentive to her domestic duties.

Dickens shared the belief of all leading Victorian reformers that more and better education was requisite if the lower classes were to be helped to better [41/42] their condition; but he also perceived that the delegated authorities used educational reform as an excuse for regimenting the minds of pupils, indoctrinating them with class prejudice and instilling an uncritical acceptance of debased values. Along with those like Paul Dombey and David Copperfield who suffer under outmoded methods of instruction, he created a gallery of youths spoiled by more progressive schooling. Included in this category are Rob the Grinder, Uriah Heep, Bitzer and Tom Gradgrind, and Charley Hexam. The descriptions of the teaching in Gradgrind's school and in the Ragged School which young Hexam attended are object lessons in how young minds are sacrificed to the application of pet theories.

Sometimes Dickens' heart leads him astray, and he presents a misleading view of the institution he is satirizing. Forster truthfully observed that "he had not made politics at any time a study, and they were always an instinct with him rather than a science." A case in point is the novelist's persistent failure to do justice to the programs for reform supported by the Philosophic Radicals. The Benthamites' dislike of administrative inefficiency and their passion for systematizing obscured his eyes to the deeply humanitarianism which prompted the efforts of these thinkers to ameliorate existing evils. Thus, the sympathy aroused for Oliver Twist's hard lot in a badly run workhouse makes no allowance for the fact that the Poor Law of 1834 was enacted to do away with the much greater hardships of outdoor relief. By the same token, the reader of Hard Times can hardly be expected to infer that the parliamentary blue books on Gradgrind's shelves contain the reports of responsible and public-spirited governmental committees created to investigate the insufferable living and working conditions of the industrial populace.[42/43] Dickens was always generous in giving credit to social agencies whose benefactions he had observed. He ardently supported the great work of Shaftesbury and Chadwick on the General Board of Health. It has been pointed out that his legal satire does not extend to the bench, although it includes unpaid magistrates like Fang in Oliver Twist, modeled on a notorious original. In the slumworker, Frank Milyey of Our Mutual Friend, and the jolly muscular Christian Canon Crisparkle in The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Dickens presented types of churchmen unselfishly devoted to their clerical duties. From first-hand experience the novelist admired the even-handed maintenance of law and order by the Metropolitan Police; and an Inspector Field of the Detective Department was the model for the admirable Bucket in Bleak House, generally accounted the first sleuth in English fiction. The setting for Johnny's death in Our Mutual Friend was based on the Hospital for Sick Children in Great Ormond Street. In 1858 Dickens was the principal speaker at a banquet which raised �3000 for this foundation.

The accusation is often lodged that Dickens social criticism, for all its cogency, is largely negative in tendency. The Utilitarian Harriet Martineau was among the first to take the novelist to task for the absence of constructive proposals in his writings, even while she granted their immense prestige. In her History of the Thirty Years' Peace she wrote:

It is scarcely conceivable that anyone should, in our age of the world, exert a stronger social influence than Mr. Dickens has in his power. His sympathies are on the side of the suffering and the frail; and this makes him the idol of those who suffer, from whatever cause. We may wish that he had a sounder social philosophy, and that he could suggest a loftier moral to sufferers....[43/44]

In rebuttal one can argue that through legislative and other means the Victorian age amended the worst offenses to which Dickens was among the first to draw attention, and that his writings demonstrably contributed to this betterment. Nevertheless, the charge is not really relevant, since it derives from a misapprehension both of Dickens' habit of mind and of his artistic purposes.

At no time did Dickens espouse any narrowly doctrinaire position, and all attempts to associate him with a school of political philosophy, whether Benthamite, Socialist, or Marxist, seriously distort his message. The London Times was nearer the mark in calling him "pre-eminently a writer of the people and for the people . . . the 'Great Commoner' of English fiction." Like Cobbett in the preceding and Carlyle and Ruskin in his own generation, his iconoclasm is of a peculiarly British stamp, an emotional blend of traditional and revolutionary elements without regard for intellectual consistency. In the term which he often used of himself, Dickens is perhaps best described as a "radical." Humphry House, who noted that this designation was still vaguely defined in the novelist's time, suggests that "by so often arrogating it to himself he helped to extend its application to cover almost any person whose sympathies, whenever occasion offered, were with the under-dog." House's opinion receives confirmation from Anthony Trollope's statement: "If any man ever was so, he was a radical at heart, believing entirely in the people, writing for them, speaking for them...." Radicalism so interpreted sets the proper context for Dickens' frequently misunderstood summary of his political faith, uttered in the year before he died to the Birmingham and Midland Institute: "My faith in the people governing [44/45] is, on the whole, infinitesimal; my faith in the People governed is, on the whole, illimitable."

As a novelist, Dickens' concern was with characters, not principles. This is simply to say that he did not think of himself as a practical reformer, responsible for advocating specific measures to eliminate the evils he deplored, but rather as a moralist whose mission was to lay bare the origins of those evils in prevalent attitudes of heart and mind. As early as 1838 a writer in the Edinburgh Review correctly identified the purport of Dickens' teaching:

One of the qualities we most admire in him is his comprehensive spirit of humanity. The tendency of his writings is to make us practically benevolent — to excite our sympathy in behalf of the aggrieved and suffering in all classes; and especially in those who are most removed from observation.... His humanity is plain, practical, and manly. It is quite untainted with sentimentality.

Through his fiction Dickens aimed at arousing the conscience of his age. To his success in doing so, a Nonconformist preacher paid the following tribute: "There have been at work among us three great social agencies: the London City Mission; the novels of Mr. Dickens; the cholera."

The moral purpose which sustains Dickens' work from beginning to end is voiced by Marley's ghost in "A Christmas Carol." In response to Scrooge's assertion that he was "always a good man of business," the ghost cries: "Business! . . . Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!" The Dickensian ideal of community spirit is perhaps most appealingly [45/46] embodied in the Christmas festivities at Dingley Dell, or in the humbler celebration of the same holiday by the Cratchit family. Such scenes led the French critic Cazamian to attribute to the author what he called "la philosophie de Noel," suggestive of a hearty but vague social altruism. In the early novels this doctrine is promulgated by a series of Santa Claus figures: Pickwick himself, Brownlow, the Cheeryble brothers, Garland, and old Martin Chuzzlewit. Gissing bitingly characterized these stories as presenting a "world of eccentric benevolence," in which the author's "saviour of society was a man of heavy purse and large heart, who did the utmost possible good in his own particular sphere."

Apart from the ministrations of such benign dei ex machina, however, Dickens looked primarily to the lower classes for evidences of that sense of kinship which represents his social ideal. In The Old Curiosity Shop he writes: ". . . if ever household affections and loves are graceful things, they are graceful in the poor. The ties that bind the wealthy and the proud to home may be forged on earth, but those which link the poor man to his humble hearth are of the truer metal and bear the stamp of Heaven." Throughout the novels there occur scenes of shared family life among the lowly and unpretending which mordantly reflect on the divisive effects of wealth and social station. Such little refuges of domestic harmony in their respective stories include the homes of the Toodles in Dombey and Son, the Peggottys in David Copperfield, and the Plornishes in Little Dorrit. But for Dickens the instinctual sympathies uniting the poor transcend the bonds of blood, and never manifest themselves more strongly than in times of hardship and distress, again in contrast to the selfish behavior of members of the privileged classes in like situations. Addressing the Metropolitan [46/47] Sanitary Association in 1850, Dickens said: "No one who had any experience of the poor could fail to be deeply affected by their patience, by their sympathy with one another, and by the beautiful alacrity with which they helped each other in toil, in the day of suffering, and at the hour of death." One recalls the devotion of Liz and Jenny, the brickmakers' wives in Bleak House, or the way the hands in Hard Times turn out to help rescue Stephen Blackpool from the mineshaft. Of the disreputable circus performers in the same novel, Dickens writes: "Yet there was a remarkable gentleness and childishness about these people, a special inaptitude for any kind of sharp practice, and an untiring readiness to help and pity one another.. . ."

The satiric intent which so uniformly underlies Dickens' social criticism, however, tends to put what he was against in bolder relief than what he was for. Whether manifested in political and economic terms as the "cash-nexus" of laissez-faire capitalism, or in religious terms as the smug self-righteousness of the Protestant ethos, or in social terms as ostentatious class snobbery, the temper of the age is subsumed for Dickens under the one all-pervasive vice of egoism. To Forster the novelist wrote of his despair for the future of a people enslaved to the doctrine of "everybody for himself and nobody for the rest." He displays this habit of mind in all its meanness in the parody of Utilitarian ethics by means of which Fagin brings Noah Claypole to heel. To avoid the gallows, says the Jew to his creature:

you depend upon me. To keep my little business all snug I depend upon you. The first is your number one, the second my number one. The more you value your number one, the more careful you must be of mine; so we come at last to what I told you at first — that a regard for number [47/48] one holds us all together, and must do so, unless we would all go to pieces in company.

Selfishness, which provides the organizing theme of Martin Chuzzlewit, conditions the behavior of other characters as formidable in their capacity to inflict unhappiness on their dependents as Bounderby, Mrs. Clennam, and Podsnap. All of Dickens' real villains are ruthlessly bent on their own interests. None represents the type better than the sinister Blandois of Little Dorrit, who cynically invokes the way of the world to justify his scheming. Asked by Clennam whether he sells all his friends, he answers: "I sell anything that commands a price. How do your lawyers live, your politicians, your intriguers, your men of the Ex- change? . . . Effectively, sir, Society sells itself and sells me: and I sell Society."

In Dickens' presentation this dog-eat-dog philosophy has extinguished the very principle of communal concern, leaving the weak perpetually at the mercy of the strong. Oliver Twist's words, while he is being led to Sowerberry's undertaking establishment, so poignantly dramatize the helplessness of the unprotected that even Bumble is momentarily abashed: "I will be good indeed; indeed, indeed I will, sir! I am a very little boy, sir; and it is so so — . . . So lonely, sir! So very lonely!" The novelist habitually chooses children and distressed members of the working class to awaken moral outrage soon visited by society on its defenseless members. And this oppression is most destructive of human dignity when it assumes an institutional form; for then it operates with complete impersonality, treating its victims like soulless objects. Thus, Jo, the crossing-sweeper of Bleak House, is always being "moved on" by authorities who do not know what to do with him, [48/49] except when he is being treated as a pawn for self-interested ends which are unintelligible to him. He is used by Tulkinghorn, by Chadband, by Lady Dedlock, by Bucket, by Skimpole. In the same way Stephen Blackpool in Hard Times, having successively served his purpose as a butt for the labor-agitator Slackbridge and for his employer Bounderby, is cast off by both to become Tom Gradgrind's tool. Stephen's dying prayer "that aw th' world may on'y coom toogether more, an' get a better unnerstan'in o' one another," is, under the circumstances, a charitable arraignment of the appalling inhumanity under which so many individuals suffer in Dickens' novels. From the disintegration of all traditions making for social cohesiveness in an age so given over to self-aggrandizement not even the family is immune. Dickens' portraits of hard-hearted parents, it has been suggested, are a reflection of his own bitterness against his father and mother for abandoning him during a crucial period in his boyhood. However this may be, the neglected children in his novels are perhaps less to be pitied than those who are callously exploited to further their parents' own selfish ends. Among those who traffic in the love of sons and daughters, sometimes but by no means always under the pretext of altruism, are Mr. Dombey and Mrs. Skewton in Dombey and Son, Turveydrop, Mrs. Jellyby, and Skimpole in Bleak House, Gradgrind in Hard Times, William Dorrit in Little Dorrit, and Gaffer Hexam and Mr. Dolls in Our Mutual Friend.

The hardships afflicting so large a part of the populace in the Victorian era produced, in reaction, an extensive and eloquent body of social criticism. Dickens' denunciation of filth and ignorance, as well as of the lack of responsible attention to those conditions and the degradation resulting therefrom, adds [49/50] nothing substantially to the preachments of Carlyle and Ruskin, and the other great reformers who were his contemporaries. Furthermore, the reader in search of factual information about conditions in the slums and factories will find fuller documentation in the work of novelists who wrote with a more obtrusively didactic purpose. As tracts for the times Disraeli's Sybil, Kingsley's Alton Locke, and Mrs. Gaskell's Mary Barton and North and South possess greater sociological value than Dickens' novels. Yet, these novels achieve an imaginative amplitude absent from more programmatically realistic treatments of the contemporary scene. For at the heart of Dickens' endeavor lay the profound conviction that man does not live by bread alone, that physical well-being is not enough if unilluminated by the vision of higher things. A piece in Household Words, entitled "The Amusements of the People," and written at the time of the Great Exhibition, summarizes the author's belief: "There is a range of imagination in most of us, which no amount of steam-engines will satisfy, and which The-great-exhibition-of-the-works-of-industry-of-all-nations, itself, will probably leave unappeased." He wrote in Hard Times:

The poor you will have always with you. Cultivate in them, while there is yet time, the utmost graces of the fancies and affections, to adorn their lives so much in need of adornment; or, in the day of your triumph, when romance is utterly driven out of their souls, and they and a bare existence stand face to face, Reality will take a wolfish turn, and make an end of you. [Dickens, of course, reserved his most forthright pronouncements on existing evils for his speeches and the pages of Household Words and All the Year Round.]

In contrast to other Victorian novels with a sense of the social pressure [50/51] of environment on the inner, as well as the outer, lives of the characters. The reader learns not only what life was like in the world portrayed, but how it really felt to have to live in such a world. Especially in the later stories, the moral atmosphere is polarized by at one extreme the hopeless despair of the lower classes, and at the other the hard-hearted complacency regnant throughout the middle class. The two tempers of mind combine to create an impression of joyless apathy, indicative of that paralysis of the social will which for Dickens seemed increasingly to be the true mal de siècle.

A scene from "The Chimes," the Christmas story for 1844, illustrates in brief Dickens' sense of how the theories of the political economists reduced human nature to a bloodless abstraction. This is the passage in which the Malthusian statistician converts to feelings of guilt Trotty Veck's innocent pleasure in his luncheon of tripe. Later in the same tale Fern speaks for the author in voicing the workingman's plea for social justice; and it is noteworthy that he does not stop with the need for better living conditions, but goes on to lay the blame for class antagonism to the systematic neglect or abuse by those in authority of all ties promoting community of interest. Dickens was making much the same point ten years later when, after a visit to the strike-bound town of Preston in preparation for writing Hard Times, he declared in Household Words that "political economy is a mere skeleton unless it has a little human covering and filling out, a little human bloom upon it, and a little human warmth in it."

On much the same grounds Dickens scorned the sectarian spirit in religion. In summarizing the articles of his own simple faith, he wrote to a clergyman on Christmas Eve 1856:

[51/52] There cannot be many men, I believe, who have a more humble veneration for the New Testament, or a more profound conviction of its all-sufficiency, than I have. If I am ever . . . mistaken on this subject, it is because I discountenance all obtrusive professions of and trading in religion, as one of the main causes why real Christianity has been retarded in this world; and because my observation of life induces me to hold in unspeakable dread and horror, those unseemly squabbles about the letter which drive the spirit out of hundreds of thousands.

The failure of religion to redeem the age from materialism Dickens laid especially to the inherence in the middle class of that sour Puritanical strain which equates salvation with worldly prosperity. Cheerless itself, it was bent on suppressing the instinct for joy in others. The type is most memorably presented in the guilt-ridden and life-denying Mrs. Clennam of Little Dorrit. Arthur Clennam places her among those whose "religion was a gloomy sacrifice of tastes and sympathies that were never their own, offered up as a part of a bargain for the security of their possessions. Austere faces, inexorable discipline, penance in this world and terror in the next�nothing graceful or gentle anywhere...." For Dickens the dismal gloom of Sundays in London epitomized all that was most forbidding in the religious temper of Victorian England. As far back as 1830 he had written under the pseudonym of Timothy Sparks a fervid pamphlet entitled "Sunday under Three Heads: As it is; As Sabbath Bills would make it; As it might be." The immediate occasion for this diatribe was Sir Andrew Agnew's Sunday Observance Bill, which the writer regarded as a conspiratorial measure on the part of the governing classes to deprive the populace of its one day in the week of carefree pleasure.

Despite his advocacy of mass education, Dickens found that too many systems of education, whether [52/53] sponsored by the state or the church, operated on the same killjoy principles. At a dinner for the Warehousemen and Clerks' Schools in 1857 he denounced all schools

where the bright childish imagination is utterly discouraged, and where those bright childish faces, which it is so very good for the wisest among us to remember in after life, when the world is too much with us early and late, are gloomily and grimly scared out of countenance; where I have never seen among the pupils, whether boys or girls, anything but little parrots and small calculating machines.

In another address the following year he developed his educational ideals with reference to Christ's manner of teaching: "Knowledge has a very limited power when it informs the head only; but when it informs the heart as well, it has a power over life and death, and body and the soul, and dominates the universe." Doubtless with the rewards of his own early reading in mind, the novelist insisted especially on the importance of nurturing the instinct for wonder in the young. Beginning with "The Mudfog Papers," which appeared in Bentley's Miscellany (1837-1838), he persistently satirized the Utilitarian doctrinaires who neglected the fancy in their insistence on the acquisition of factual information. His most masterful treatment of this theme occurs, of course, in Hard Times. The textbook definition of the horse which enables Bitzer to show up Sissy Jupe makes no provision for the dancing circus animal that foils his pursuit of Tom Gradgrind. And in the face of the havoc wrought by his educational theories, Mr. Gradgrind is brought humbly to acknowledge the supremacy of Sissy's impulsive wisdom of the heart. Sleary's account of the devotion exhibited by Mr. Jupe's performing dog stands as the [54/55] final comment on Dickens' meaning. "It theemth," the circus-master says to Gradgrind

to prethent two thingth to a perthon, don't it, Thquire? . . . one, that there ith a love in the world, not all Thelf-interetht after all, but thomething very different; t'other, that it hath a way of ith own of calculating or not calculating, whith thomehow or another ith at leatht ath hard to give a name to, ath the wayth of the dogth ith!

The preliminary notice to Household Words set forth the goals which Dickens hoped to realize in his weekly:

No mere utilitarian spirit, no iron binding of the mind to grim realities, will give a harsh tone to our Household Words. In the bosoms of the young and old, of the well-to-do and of the poor, we would tenderly cherish that light of Fancy which is inherent in the human breast; which, according to its nurture, burns with an inspiring flame, or sinks into a sullen glare, but which (or woe betide that day!) can never be extinguished. To show to all, that in all familiar things, even in those which are repellent on the surface, there is Romance enough, if we will find it out: — to teach the hardest workers at this whirling wheel of toil, that their lot is not necessarily a moody, brutal fact, excluded from the sympathies and graces of imagination; to bring the greater and the lesser together, upon that wide field, and mutually dispose them to a better acquaintance and kinder understanding -- is one main object of our Household Words.

The same controlling purpose carried over to All the Year Round, in which the editor announced that he would continue to strive for "That fusion of the graces of the imagination with the realities of life, which is vital to the welfare of any community...." A like intent was to the fore in Dickens' fiction. The Preface to Bleak House states that in this story he had "purposely dwelt on the romantic side of familiar [54/55] things." Any estimate, therefore, of the significance of Dickens' novels as social commentary on their age must take into account the author's concept of his dual function as critic and entertainer.

As he clarified his social vision, Dickens at the same time discovered more imaginative means of projecting that vision. Although the discussion of the formal aspects of his achievement properly belongs to the later chapters of this volume, some indications may here be given of how the writer combined extraordinary astuteness in his response to the life of the age with the ability to transmute his observations into themes of enduring relevance. As a result, his work surmounts the limitations of both the roman social and the naturalistic novel: the one confined to topicality by its didactic purpose, the other overly literal in its striving for verisimilitude.

Of Dickens' novels, Bleak House, Hard Times, Little Dorrit, and Our Mutual Friend are the richest in reference for the student of Victorian life. Scholars have demonstrated the historical accuracy of most of the situations in these stories, whether it be the spreading pestilence of Bleak House, the labor unrest in Hard Times, or the financial panic in Little Dorrit. Yet, the author has so generalized his treatment of contemporary phenomena that they transcend their localized settings. Bleak House came out at a time when a series of ministerial crises was underscoring the want of responsible leadership in England; but it is not necessary to have these facts in mind to recognize in the goings on at Chesney Wold a timeless satire on political patronage and the spoils system. Similarly, although the Circumlocution Office in Little Dorrit was immediately inspired by the revelation of flagrant mismanagement on the part of all departments entrusted with the conduct of the Crimean War, Dickens' indictment of [55/56] bureaucratic red tape and muddleheaded officialdom has lost none of its cogency.

The novelist's success in harnessing reforming zeal to artistic ends is perhaps most apparent in his development of associative images. The fog which shrouds the opening of Bleak House by metaphoric expansion embraces the murky procedures of Chancery. In the same way Old Harmon's dust-mounds in Our Mutual Friend, real enough as a feature of the city landscape, emblematically represent the whole sordid, money-grubbing basis of capitalist economy. In contrast to the baldly factual accounts of tenement and factory conditions provided by other novels of the period, Dickens' method in Hard Times is impressionistic. The description of Coketown does not insist on the unguarded machinery in the mills or the open sewers under the dwellings, but rather, evokes the deadening monotony which was the truly brutalizing element in the lives of the workers. It is doubtful, however, whether any amount of naturalistic reportage could impart so indelible a sense of the blighting effect of the machine age on the human spirit as the fanciful breadth of the following description:

It was a town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it; but as matters stood it was a town of unnatural red and black like the painted face of a savage. It was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled. It had a black canal in it, and a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows where there was a rattling and trembling all day long, and where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness. It contained several large streets all very like one another. and many small streets still more like one another, inhabited [56/57] by people equally like one another, who all went out at the same hours, with the same sound upon the same pavements, to do the same work, and to whom every day was the same as yesterday and to-morrow, and every year the counterpart of the last and the next.

Last modified 4 November 2011