Photographs are by Susan Cooke unless otherwise stated. Special thanks are also due to guide Annette Mullen, whose generous sharing of knowledge enabled me to understand the Necropolis and the intricate stories of its inmates. [Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

An etching of the Necropolis (from an unknown publication) as it appeared in the 1830s (author's collection).

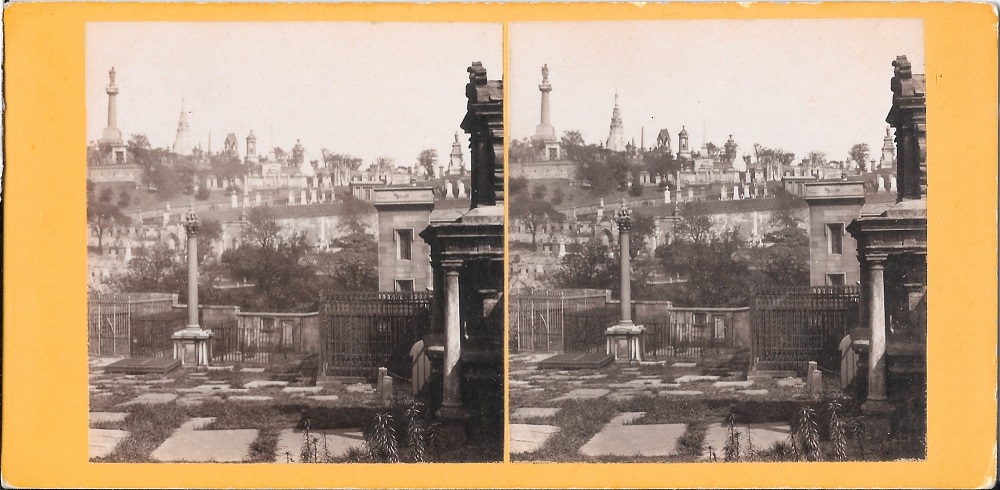

Two early views of the Necropolis, from the author's collection. Left: A stereoscopic image of the cemetery by Alex Inglis, photographer of Edinburgh, circa. 1865. Right: a postcard from 1901. The site’s appeal to the public as a spectacle seems surprising to modern tastes – a view was even issued as the centre-piece of a Valentine card.

The Glasgow Necropolis is one of the most impressive of Britain’s Victorian cemeteries, and bears direct comparison with the London burial grounds, Highgate and Kensal Green. Positioned on a hill overlooking Glasgow, the Necropolis is a dominating visual presence, creating a Gothic skyline of ‘spiky obelisks and pinnacles’ (Brooks 58) which has acted as a backdrop and inspiration for television and film. Matt Reeves composed a sequence in The Batman (2022) against the cemetery’s evocative outline, and Steven Moffat was inspired by its stone angels, using them as a source of grotesque imagery in Blink, the most celebrated episode of the modern revival of the BBC series, Dr Who (2007).

Left: Looking westward towards Glasgow Cathedral, which shows the cemetery’s high elevation. Right: A view from a pathway circulating the site as it ascends the hill, with the gravestones neatly arranged on the terraces to create the ‘streets’ of the City of the Dead.

Imposing as a spectacle, the Necropolis is now a tourist destination and is explored by many thousands of visitors. Attractive in its own time, when it acted as a leisure park for moral improvement and exercise, it is still an object of fascination, and probably draws far more spectators than either of the London cemeteries. Part of its appeal lies in its state of preservation, which differs radically from the English sites. In marked contrast to Highgate, which has been abandoned to re-wilding, Glasgow City Council have maintained the Necropolis essentially as it appeared in its own time; although many of its monuments have subsided, collapsed, or weathered so as to be illegible, it is not strangled by ivy and overgrowth, and its paths and greensward are kept in good order. The object of municipal pride, the cemetery has inevitably been the subject of Glaswegian satire as well. As the comedian Billy Connolly observed in one of his jokes, the care directed at the Necropolis was typical of the city’s misdirection of resources, paying more attention to the dead than to the living.

More views of the cemetery. Left: Ascending south-east. Right: Some graves on the summit (© Chris Downer, reproduced under the terms of Creative Commons licence (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-59/2.0).

Yet the Necropolis does not appear to be as well-known as it might be among scholars of Victorian architecture. Though the subject of several histories, it is only mentioned in Chris Brooks’s extensive analysis of burial practice, Mortal Remains (1988), and Brooks does not accord it its full importance as a prime example of Victorian management of the dead. In fact, the Glasgow Necropolis is an exemplar of the ways in which nineteenth century cemeteries were conceived and created: though very much eclipsed by Highgate and Kensal Green, it was contemporaneous with each of these sites, and is just as significant.

Origins

Positioned to the east of Glasgow Cathedral, the Necropolis occupies a large site of 37 acres, the same size as Highgate, but much smaller than Kensal Green (77 acres). Set up as an interdenominational cemetery, it contains around 50,000 interments, but only 3,500 monuments. The great majority of the burials were the unmarked graves of the poor, while the others were those of the middle-classes, who marked their graves with a range of tombs from simple standing stones to elaborate mausolea. As in all Victorian cemeteries, status and class were registered even in death, with the wealthiest incumbents having graves at the top of the hill in adjacency to the John Knox monument (1825), and the humbler dead being positioned on the terraces on either side of the ascending pathways. In this sense the cemetery emblematizes the Victorian class system – with the richest ascending skyward so that the (putative) great and good were literally nearer heaven than the insignificant.

The Necropolis was established in 1833, the same year as Kensal Green and six years before Highgate. Its model, like the London cemeteries, was Père Lachaise in Paris (1804), and its primary advocate was Dr John Strang. In 1831 Strang published a short manifesto, Necropolis Glasguensis, urging the members of the Glasgow Merchants’ House to convert Fir Park, which the organization owned, into a ‘garden cemetery’ (vi) for the city’s citizens. Some of Strang’s polemic is concerned with practicalities such as the costs of furnishing what was otherwise a bare site with ornamental shrubbery, but his primary arguments for establishing such a place have a wider application.

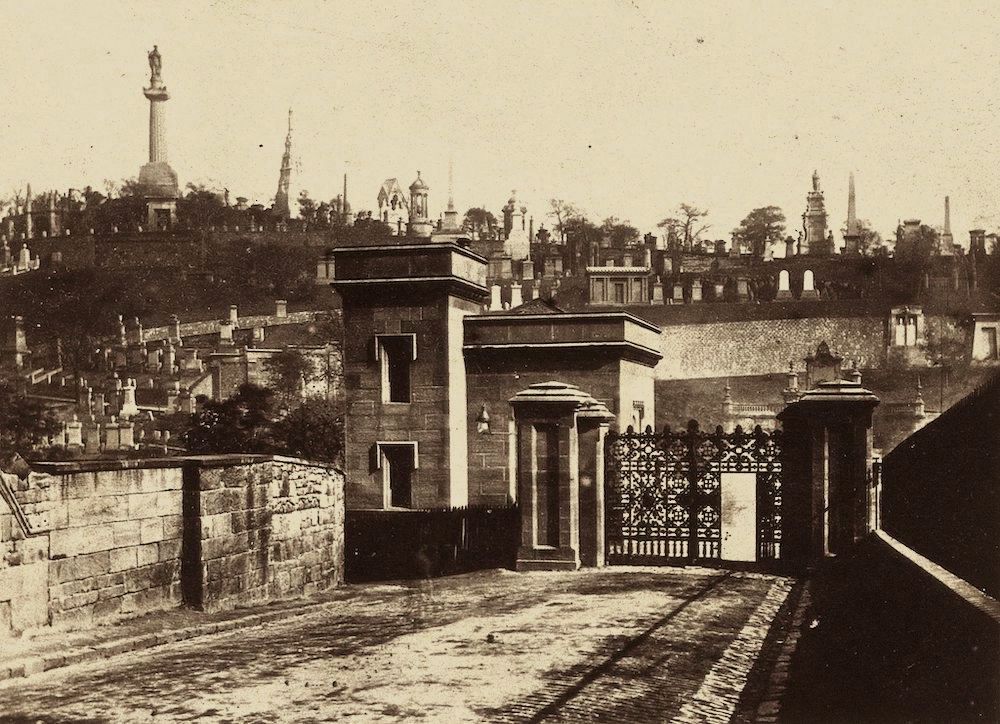

Before and after. Left: 'View of ground for proposed cemetery' (frontispiece to Strang). Right: The main entrance of the Necropolis, showing the metal gates that include the heraldic device of the Glasgow Merchants (from the Wellcome Collection, also in the public domain).

The need for such a cemetery, he argues, was essentially two-fold, and his motivations for establishing a Necropolis were the same as those which had led to the setting up of the Parisian prototype. One pressing issue was public health and the healthy disposal of the deceased. Glasgow, a rapidly expanding industrial city, was suffering, Strang insists, from the unhygienic effects of overcrowded churchyards. This was simply dangerous; as Strang observes of all Scottish cities, but especially of Glasgow:

Every square yard [of the burial grounds] contains not only piles of mouldering bodies, but a proliferation of rank and noxious weeds, situated in the very core of a populous and crowded city, [a situation which] can be considered as little better than a generator of plague and pestilence. [34]

Such places, he remarks, have the features of a ‘disgusting charnel house’ (24). Strang’s argument was in line with pythogenic theory, postulating the contemporary idea, as Brooks explains, that ‘the gasses given off by human putrefaction could be deadly to anyone who inhaled them’ (31). What was clearly needed, Strang believed, was a ‘more sanatory [sic] mode’ (Strang 34) of disposal. The proposed Necropolis would fit this bill, taking the dead out of the congested boneyards and putting the departed in a single spot open to the elements above the city and refreshed by wind; if there were any question of putrid gasses, they would be blown away or absorbed by the cemetery’s flora. The concern for safe disposal would be further facilitated by burying the dead in brick-lined graves along with a meticulous recording of the inmates’ details.

These considerations reflect Strang’s medical training and concern for municipal welfare: ‘let Glasgow … look to the wretched and neglected state of her churchyards and endeavour to improve them’ (65). Yet he was equally concerned with the proposed cemetery’s role in improving public taste and behaviour, believing it would be ‘beneficial to public morals’ (58). According to him, the ‘careless and slovenly’ (24) state of existing burial grounds meant that the spiritual experience of remembering the dead and reflecting on the divine had been eroded, replacing the ‘solemn and affecting’ experience of ‘devotion’ with ‘feelings of aversion and disgust’ (24). The provision of a beautiful place, combining hygienic disposal with an appealing garden and beautiful, well-maintained tombs, would, Strang believed, re-instate those holy feelings, creating refinement where there was previously only degradation and horror.

The development of a ‘picturesque and romantic’ estate (58) would fulfil both of Strang’s demands, and the Glasgow Merchants, who had been considering the proposal since 1828, put the project out to tender with a cash prize. Sixteen plans were submitted, and the winners were David and John Bryce; however, the Committee decided it would be better handled by a landscape gardener and employed George Mylne as the Superintendent. The Necropolis opened in 1833, although some interments, including one in the Jewish section, had taken place in 1832.

Funerary Art and Geography

The placing of the Necropolis on Fir Park was by no means an easy option, given the problematic nature of the site. Writing in 1857, George Blair notes how ‘on the whole, the elevated portion … is almost entirely a mass of solid rock, covered in some places with scanty soil’ (43). This geological set-up meant that many of the graves had to be ‘hewn or blasted out’ (43) of the bedrock, and the site as a whole had to be excavated to form a series of terraces linked by paths which were placed so as to lead from the base to the summit.

The transformation of a rocky hill into a garden was a feat of landscape gardening, and represents yet another example of the tenacious ingenuity of Victorian planners. The graves are placed in linear rows on the lower part of the Necropolis, while those on the flat top of the hill are placed into avenues. This is indeed a city of the dead, with streets and thoroughfares, creating a sense of space and orderliness which is quite unlike Highgate’s congestion. Such municipality is further emphasised by the elaborate gateways and the Bridge of Sighs, which crossed the Molendinar Burn before the stream was diverted into a culvert in 1877.

Two views of the Jewish cemetery. Left: This shows the steep and narrow site, which finally contained more than 50 graves. Right: The original entrance, embellished with a Star of David which marks the restoration of 2015.

These architectural features were part of the cemetery’s aim to improve public taste. Landscaped in accordance with Picturesque aesthetics, and looking more like a country estate than a boneyard, the space was eventually occupied by tombs embellished in the most ‘refined’ and diverse styles of the period. Every type of Victorian idiom can be found: classicism predominates, but there are also numerous examples of Gothic, Romanesque, Renaissance and even British Art Nouveau. The most impressive graves and mausolea are those of Glasgow dignitaries, including a monumental figure-sculpture depicting the industrialist Charles Tennant, an elaborate Renaissance mausoleum for the engineer James Dunlop, and a Gothic headstone for controversial Professor of Anatomy, James Jeffray; equally extravagant are the Norman temple for Major Archibald Douglas Monteath of the East India Company and the Gothic tomb for Margaret Montgomerie.

Three tombs in diverse styles, commemorating: a) the anatomist James Jeffray (1848); b) the industrialist Charles Tennant (1838); and c) the engineer James Dunlop (1893), this last photograph © Stephen C. Dickonson, reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC Attrribution-Share Alike 4.0 International licence.

Bibliography

Blair, George. Biographic and Descriptive Sketches of the Glasgow Necropolis. Glasgow: Ogle, 1857.

Brooks, Chris. Mortal Remains. London: Wheaton & The Victorian Society, 1989, new ed. 1992.

Strang, John. Necropolis Glasguensis. Glasgow: Atkinson, 1831.

Created 15 September 2023