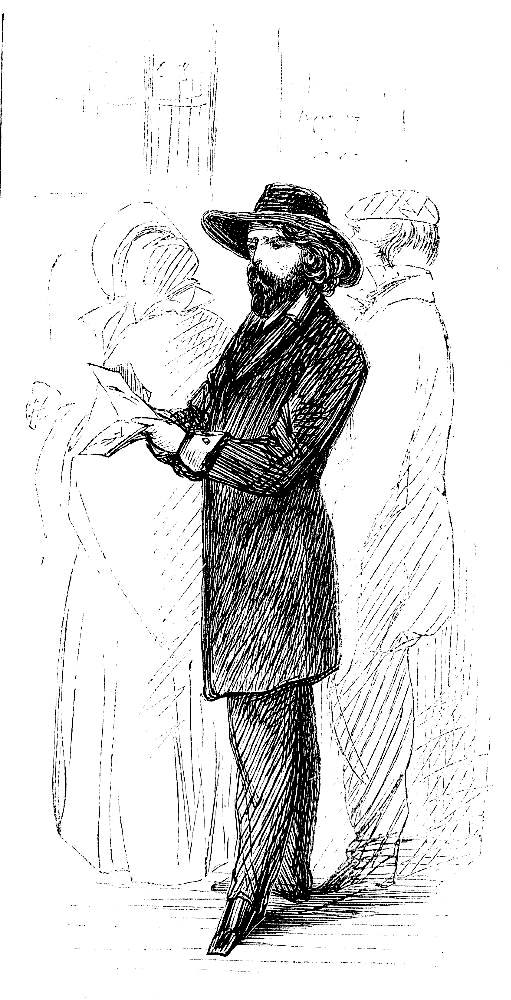

Hartright reads Mrs. Catherick's extraordinary letter.

John McLenan

28 July 1860

10.5 cm high by 5.5 cm wide (4 ⅛ by 2 ⅛ inches), vignetted.

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for the thirty-sixth weekly number of Collins's The Woman in White: A Novel (28 July 1860), 469; p. 226 in the 1861 volume.

[Click on the image to enlarge it.]

McLenan flags Hartright's reading a letter with some concern at the head of the instalment. Coming shortly after the death of Sir Percival Glyde, the anonymous letter provides significant details about his earlier forgery of the record of his parents' wedding at Old Welmingham, his motivation in breaking into the vestry, and his relationship with Mrs. Catherick and her daughter, Anne.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.