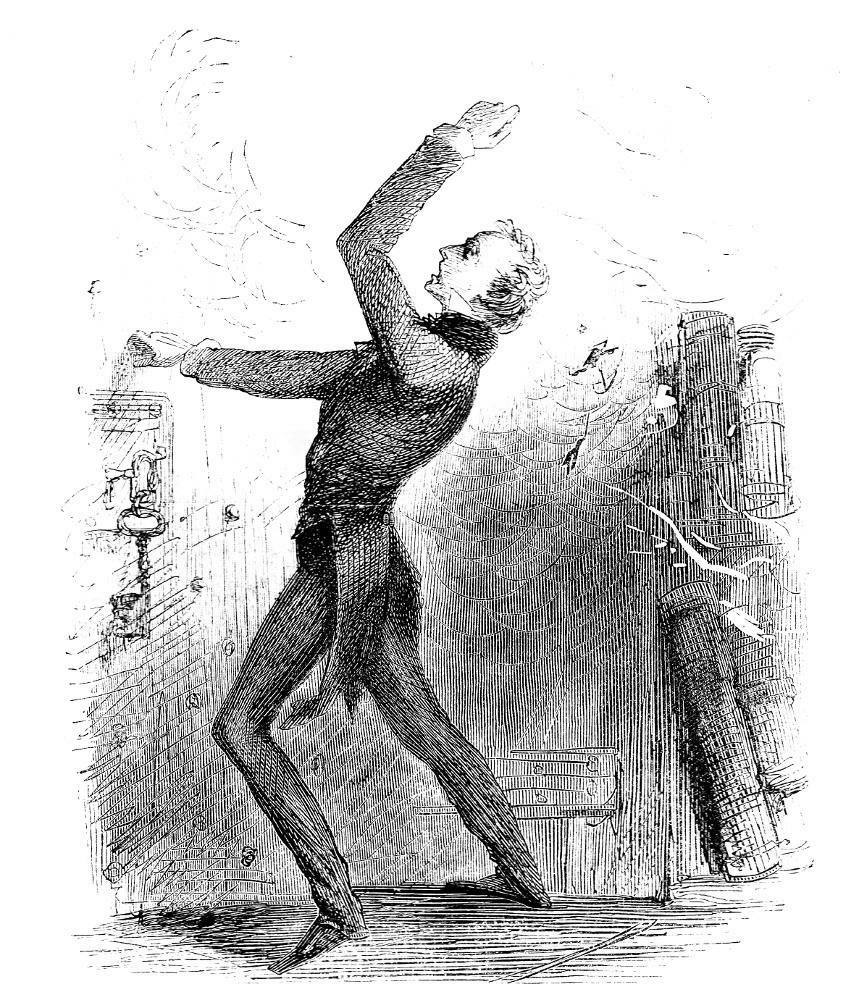

"The smoke and flame, confined as they were to the room, had been too much for him."

John McLenan

21 July 1860

11.2 cm high by 8.7 cm wide (4 ⅜ by 3 ⅜ inches), vignetted, p. 453; p. 219 in the 1861 volume.

Thirty-fifth regular illustration for Collins's The Woman in White: A Novel (1860).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.