I am indebted for her assistance to Fiona Waterhouse, Research Assistant at the Art and Design Archive, City University, Birmingham.

The Pre-Raphaelite Movement developed in three phases, stretching from the middle of the nineteenth century until the Edwardian period, and with some of its imagery lingering into the 1920s. The Brotherhood was set up in 1848 under the direction of Dante Rossetti, J. E. Millais and William Holman Hunt; the second generation was carried forward by Frederick Sandys, Edward Burne-Jones and J.W. Waterhouse; and a final development, in the 1890s, was projected by artists such as Paul Woodroffe, Arthur Gaskin and Laurence Housman. These figures made significant contributions to the discourse of Pre-Raphaelitism, appropriating and modifying its visual language for their own purposes. There were however a number of lesser practitioners in the idiom whose art has been largely forgotten.

One such artist, active in 1890s, was Frederick Godwin Mason (1864–1939, usually identified only as ‘Fred’), an illustrator and book-cover designer who produced a small but interesting body of work. Born into a middle-class family in Yardley, Birmingham, trained at the Birmingham Municipal School of Art, and later becoming the head-teacher of the art-college in Taunton, Mason is usually consigned to the footnotes of history. His figurative work is essentially Rossettian Pre-Raphaelitism and his decorative borders are derived from William Morris’s Arts and Crafts arabesques; but these ornamental pieces simultaneously reflect the impact of Art Nouveau as it was practised, among others, by Aubrey Beardsley and Charles Ricketts. Always an eclectic artist who skirts dangerously close to the borders of plagiarism, Mason manipulates these competing idioms to create well-crafted images, engraved on wood, in strict sympathy with their subjects. Mason is also important as a Birmingham artist who benefitted from studying at what was then one of the most advanced institutions in the United Kingdom, and his progression from student to professional exemplifies the interlocking of training and practice. Though never considered before, these issues are explored here, drawing on unpublished material from the archive of the University of Central England and other materials.

Mason’s immediate influence was Arthur Gaskin, a teacher and designer whose educational practice was informed by John Ruskin’s revolutionary ideas on the value of craft as the vehicle of moral, aesthetic and social reform. He was also (in all probability) one of the students who attended Morris’s address to the college in 1894 where he would have heard from Morris’s own mouth the need to overturn the ‘tyranny [of] utilitarianism’ (2) and revolutionize taste by creating beautiful things, which for the maker is ‘the greatest pleasure in the world’ (25).

Most importantly of all, Mason was trained in the manner of Pre-Raphaelitism and its practical expression in Arts and Crafts. Placed under the radical direction of the head-teacher Edward Taylor, he followed a curriculum which emphasised the practicalities of making, taking a design from the drawing-board to its materialization. This process was systematically teased out in the form of a series of experientially-based training activities or ‘Art Laboratories’, covering work in two and three-dimensional design, figure and landscape drawing, metal-work, and experimentation with materials.

Mason experiments with the conventions of a Morrisian style. He is particularly interested in the overlap between the floral designs of Arts and Crafts and the imagery of Art Nouveau, which in the nineties was being popularized by the work of Aubrey Beardsley, C. R. Mackintosh and others associated with the Glasgow School of Art.

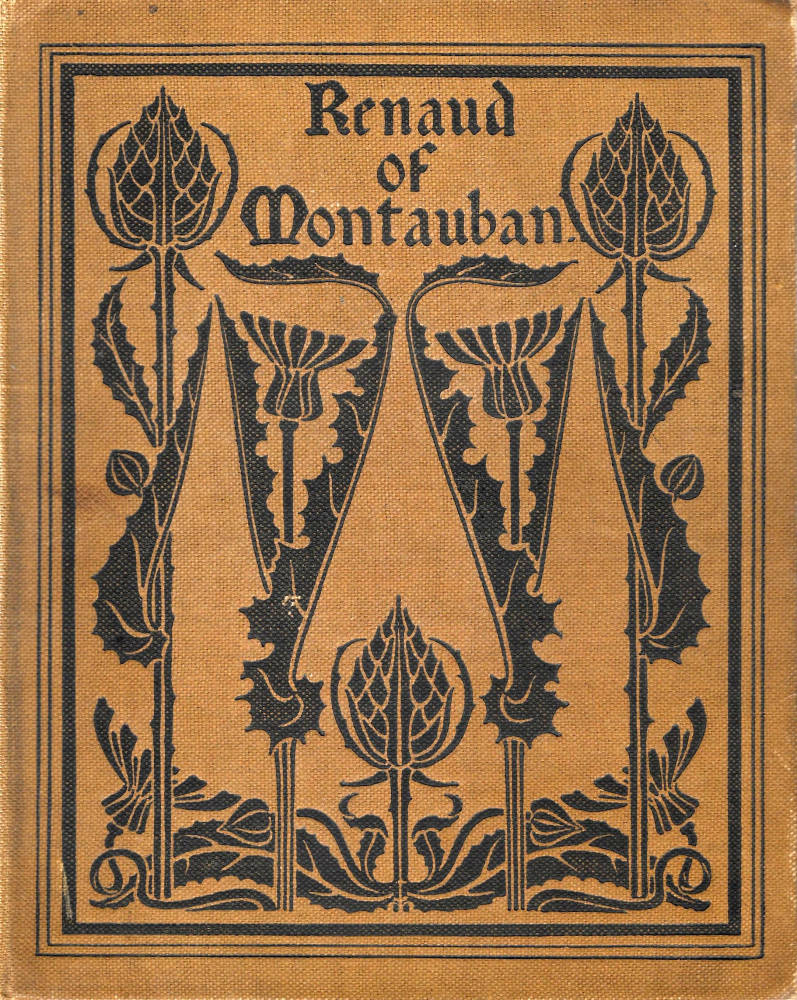

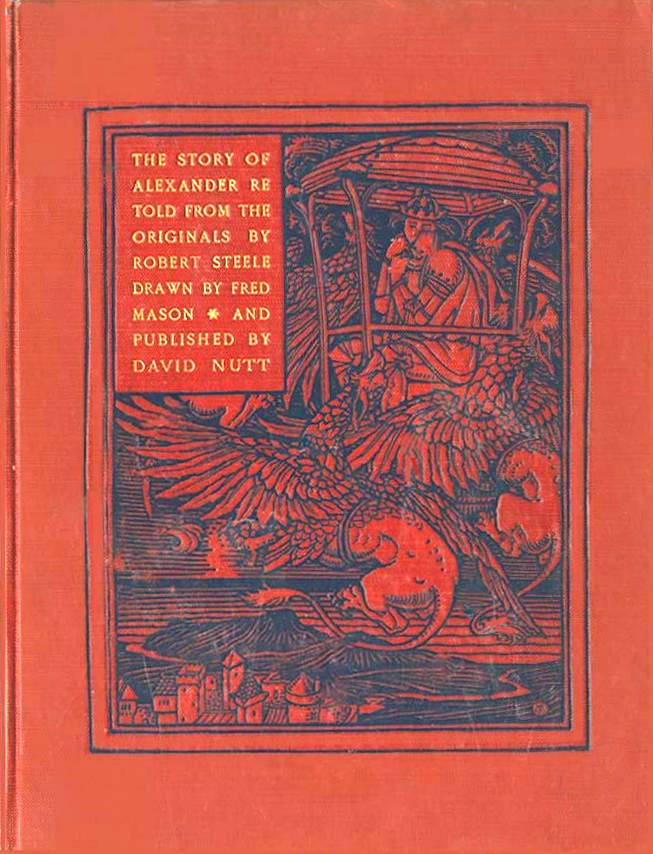

Three of Mason’s bindings: Left: Huon of Bordeaux. Middle: Renaud of Montauban. Right: The Story of Alexander. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Mason designed bindings for all three of his collaborations with Robert Steele. Mounted on buckram cloth and bearing complicated patterns, they are classified by Malcolm Haslam as ‘Arts and Crafts book covers’ (64–5). However, this judgement is only partly accurate: the front cover of The Story of Alexander, essentially an illustration stamped in black, is certainly in the idiom of Arts and Crafts; but the other bindings, for Renaud of Montauban and Huon of Bordeaux are abstract pieces of Art Nouveau. Separated from Alexander by only a year and three years respectively, the two later bindings embrace the aesthetics of the end of the century.

Both are elaborate, stylized pieces which refigure floral motifs as simplified abstractions in the manner of Selwyn Image and Charles Ricketts. Huon, especially, can be linked to specific exemplars in the form of Image’s design for The Tragic Mary (1890) and Ricketts’s cover for Oscar Wilde’s Poems (1892). Renaud, a curious combination of curving arabesques and geometrical verticals, is similarly of its time, and it is interesting to compare this design with bindings by A. A. Turbayne and Gleeson White.

Related material

- Frederick Godwin Mason (homepage)

- Fred Mason’s Training and Illustrations

- Fred Mason, William Morris, and Decorative Features of Mason’s Books

Bibliography: Archival Material

Ancestry.co.uk.

Material in Minutes Books and slide collection of the Art and Design Archive, City University, Birmingham, UK.

Bibliography: Primary Material

A Book of Pictured Carols. London: George Allen, 1893.

The Century Guild Hobby Horse (1886–92).

Field, Michael [Katherine Harris Bradley & Edith Emma Cooper]. The Tragic Mary. London: George Bell, 1890.

The Quarto.Birmingham: Cornish Brothers, 1894–6.

Steele, Robert (translator). Huon of Bordeaux. London: George Allen, 1895.

Steele, Robert (translator). Renaud of Montauban. London: George Allen, 1897.

Steele, Robert (translator). The Story of Alexander. London: David Nutt, 1894.

Wilde, Oscar. Poems. London: Elkin Matthews & John Lane, 1892.

Bibliography: Secondary Material

‘Birmingham Municipal School of Art.’ Birmingham Daily Post (26 July 1892): 5.

Haslam, Malcolm. Arts and Crafts Book Covers. Shepton Beauchamp: Richard Dennis, 2012.

Morris, William. An Address by William Norris at the Distribution of Prizes to Students of the Birmingham Municipal School of Art. London: Longmans, 1898.

Valance, Aymer. ‘A Provincial School of Art.’ Art Journal (1892): 344–8.

Last modified 29 September 2019