Photographs by John Salmon, text and formatting by Jacqueline Banerjee. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit John Salmon and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images to enlarge them.

Memorial plaque to Arnold Heseltine (1852-1897), to whose memory — as well as to the glory of God — the church was dedicated.

Arnold Heseltine (1852-1897) was a London solicitor, and the father of the composer Philip Arnold Heseltine, who took the pseudonym of Peter Warlock (see Smith). When he died, his wealthy stockbroker brother Evelyn gave the land for a new parish church to be built in his memory, and was its chief benefactor — according to the listing text, to the tune of £5000. There was to be no stinting on it. The simplicity of the exterior, with its understated refinements, was a choice, and so too was the richness of the interior, which would include the use of fine aluminium sheeting, which Wendy Hitchmough tells us was as costly at this time as silver (102).

The Interior

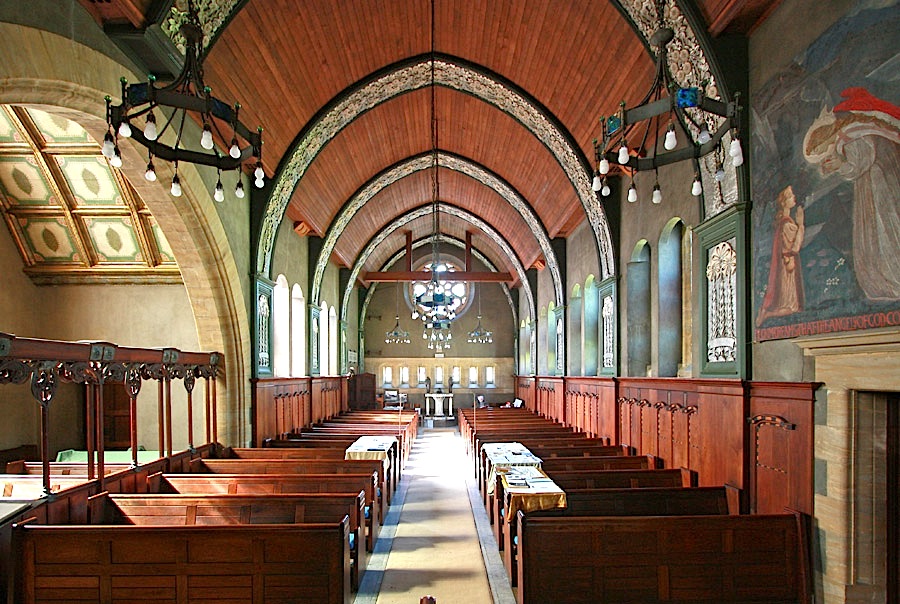

Looking east to the chancel and apse.

The nave is wagon-vaulted, like that of Townsend's St Martin's, Blackheath, with an apse to the east, and a south chapel. The south porch entrance is on one side, and the vestry door on the other, near the organ. As intended from the beginning, the architectural form created by Townsend was royally adorned inside by fittings devised and mostly executed by William (subsequently Sir William) Reynolds-Stephens. This was planned with a particular eye to the colour and contrasting effects of different materials, symbolic detailing, and, above and through all, spiritual meaning. The impressively broad five-bay vault, for example, is panelled in rich walnut, relieved by green ribs, themselves highlighted by embossed rose-trees and lilies in aluminium leaf, in glowing tribute to the church's dedicatee.

Juxtaposing various materials was a particular feature of these Arts and Crafts years, and perfect for the versatile Reynolds-Stephens, who for some years now had been closely associated with the movement. It seems there was no medium to which he could not turn his hand, as both artist and craftsman. Even the hanging lights have enamel panels to their iron frames, as well as "flower bud metal shades and glass bead finials" (listing text; see the illustration of this taken from A. L. Baldry's article on the church, for a closer view). In contrast, the ranks of sturdy choir-stalls and pews, designed by Townsend himself, have simple lines, minimally carved ends without finials, and a quiet dignity. Not only has the architect left their form and craftsmanship to speak for themselves, as he liked to do, but he has also shown a certain generosity in not letting them draw any attention away from Reynolds-Stephens's effects. But there could be a clue to modern preferences here, in James Bettley's remark that these particular furnishings were "designed less excessively by Townsend" (430).

The Chancel and Sanctuary

Left: The chancel, with the chancel screen. Right: The sanctuary.

The use of colour and contrast here is breathtaking, however. The stated intention of the change from the darker wooden nave vault to the shimmering aluminium-clad apse was to lead the eye and spirit "onward ... to the glorified and risen Christ" (quoted in Bettley and Pevsner from a contemporary Explanatory Memorandum for the congregation [430]). The aluminium overhead in this half-dome is patterned with a grape-bearing vine rising from behind the reredos, and Baldry rightly talks of the "exquisite play of light and shade" that the whole composition produces ("A Notable Decorative Achievement," 12). The brass and bronze chancel screen in between nave and choir is another scintillating work of art, in the form of blossoming fruit trees with mother-of-pearl petals and rich red glass pomegranate fruits, each stem enfolding at the top an angel bearing a scroll inscribed with one of the virtues (see Hitchmough 104; Davy 119). According to the church's own website, St Mary's is affectionately known as the "Pearl Church." See Part III for closer views of the altar, reredos and screen.

The Apse

Looking upward into the ceiling of the apse.

Below the silvery aluminium is a curved wall faced with grey-green "cippolino variegated marble" (listing text), while the warm stone of the double sanctuary arch is the same as that seen around the windows both inside and out, creating a pleasant link between interior and exterior effects. Baldry writes enthusiastically about the way architect and designer have collaborated here. They have got the balance exactly right, he says, and he makes an important point in the second part of this sentence: "The architectural and decorative features are correctly adjusted, the construction of the building is neither concealed nor stultified by added ornamentation" ("A Notable Decorative Achievement," 4; emphasis added). Reynolds-Stephens has played his part generously, too, in this collaboration.

The South Chapel

Left: The parclose screen separating off the south chapel. Right: The south chapel.

The screen separating off the side chapel is wooden, with its posts ending in "linked poppy leaves," with flowers studding the top rail (listing text). This chapel was originally for the Heseltine family, but it was turned into a war memorial chapel towards the end of World War I, when Reynolds-Stephens designed and sculpted the relief for the reredos, showing the body of Jesus in the sepulchre being watched and prayed over by two angels. See Part III for a closer view. The ceiling of the chapel is coffered and painted now, but originally matched that of the nave (see Bettley and Pevsner 430).

The West End

Left: The west end from the chancel. Right: The west end from the top of the nave. Note the row of baptistry windows at the back, under the rose window.

On top of the chancel screen is the rood cross with an angel either side, and the right-hand photograph gives a view of the painting over the entrance to the north vestry: "Pilgrim Dreams that the angels of God come to him with heavenly food" — evidently inspired by Bunyan. It came from the chapel when that was converted to a memorial space, and covers windows here from which the stained glass had earlier been removed. The painting is thought to have been the work of Louis Davis (1860-1941), another artist associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, who designed the original stained glass in the baptistry area. Like the original nave windoows by Heywood Sumner, Davis's row of seeven narrow baptistry windows under the rose window at the west end was lost because of bomb damage in World War II. So it is good that another of Davis's contributions to the church is still intact. In 1946, new stained glass was installed in those seven windows, as shown immediately below (these are the ones that make such a striking feature on the west elevation). Examples of stained glass in the church by other designers are given separately (see "Related Material" below for links).

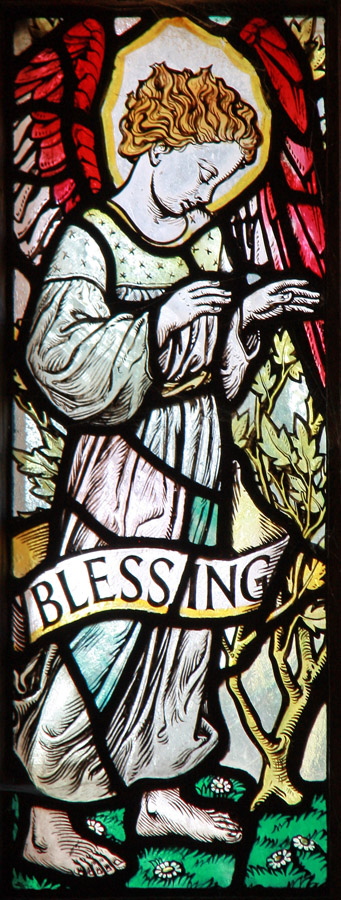

The seven replacement baptistry windows. Although not the original ones, these are of interest because they were designed by James Hogan (1883-1948), working for the long-established firm James Powell & Sons — whose stained glass studio closed only in 1973. The youthful angels walk on grass studded with daisies. Symbolic details, such as an eagle in the one representing power, and an owl in the one representing wisdom (fourth and fifth from left) contribute to their meanings.

There is some debate about how to place St Mary's in the history of design. James Bettley and Nikolaus Pevsner consider it to be "the supreme exemplar or Arts and Crafts workmanship, overlaid with that most un-English of styles, Art Nouveau" (430), but how far does it express or embody the latter? According to biographer Mark Stocker, Reynolds-Stephens himself would not have wanted to be associated with Art Nouveau: "Like most of his arts and crafts contemporaries, he regarded the style as one of decorative excess." This matter is more fully discussed elsewhere on our website. There is general agreement, however, that St Mary's has one of the most remarkable church interiors in England. Simon Jenkins speaks for many when he calls it a "wondrous church" (218).

Related Material

- Arts and Crafts or Art Nouveau? W. Reynolds-Stephens and the Interior of St Mary the Virgin, Great Warley (Discussion)

- St Mary the Virgin, Great Warley, I: Exterior

- St Mary the Virgin, Great Warley, III: Fixtures and Fittings

- "A Notable Decorative Achievement by W. Reynolds-Stephens"

- "The Work of W. Reynolds-Stephens"

- [Stained Glass] West Window to Heywood Sumner's designs

- Praise Him in the Height and O Praise the Lord of Heaven, a pair of windows to Heywood Sumner's designs

- Apse windows designed by William Reynolds-Stephens

- South Chapel window by Morris & Co. to Edward Burne-Jones's design

Bibliography

Baldry, A. L. "A Notable Decorative Achievement by W. Reynolds-Stephens." The Studio. 34 (1905): 1-15. Internet Archive. Web. 19 June 2015. [Whole text on the Victorian Web.]

_____. "The Work of W. Reynolds-Stephens." The Studio. 17-19 (1899): 75-85. Internet Archive. Web. 19 June 2015. [Whole text on the Victorian Web.

Bettley, James, and Nikolaus Pevsner. Essex. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007.

"Church History." St Mary the Virgin, Great Warley. Web. 19 June 2015.

Davy, Peter. Arts and Crafts Architecture. London: Phaidon, 1995.

Hitchmough, Wendy. "Great Warley Church: Architecture and Sculpture — body and soul." In Architecture 1900. Ed. Peter Burman. Lower Coombe, Dorset: Donhead, 1998. 99-108. [This is the version on Google Books, but it was also published by Routledge.]

List Entry for St Mary the Virgin. Historic England. Web. 19 June 2015.

Powell, W. R., ed. "Great Warley." In A History of the County of Essex, Volume 7. London, 1978. 163-74. British History Online. Web. 19 June 2015.

Smith, Barry. "Heseltine, Philip Arnold [pseud. Peter Warlock] (1894–1930), music scholar and composer." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 19 June 2015.

Stocker, Mark. "Stephens, Sir William Ernest Reynolds (1862–1943), artist." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 19 June 2015.

Created 19 June 2015

Last modified 14 April 2025