[In preparing the following text for reading on the web, I have tried to place images of Reynolds-Stephens's work as close as possible to their location in the orginal article in The Studio, where they are much larger (from 4 to 6 inches). I have also indicated page breaks of the printed text in the following manner: [183/184]. Clicking on thumbnail images will produce larger pictures. — George P. Landow]

ALTHOUGH the most obvious tendency of the present-day demand for art work is to drive the producers into the narrowest type of specialism, and to limit each one's effort to certain classes of achievement, there are happily still active amongst us some few artists who have both the inclination and the capacity to rebel against these restrictions, and to strive for wide independence of thought and practice. These men refuse to be bound” by the popular fancy, or to give way to influences which cramp and pervert the assertion of their individuality. They hold strongly the creed that the true mission of the art worker is to prove himself capable of many things, to show that he has an all-round knowledge of the varieties of technical expression, and a practical acquaintance with many methods of stating the ideas which are in his mind. Instead of seeking to find one particular direction in which they can, by scrupulous attention to business, secure an extensive custom, and instead of making up their minds'to continue for the rest of their lives active only in the repetition of that one idea which proves to be acceptable to a large section of the public, they regard their successes in one branch of art only as incentives to widen their scope, and as justifying them to aim at achievements equally successful in other branches. Among the many men who are content to plod along a beaten track, seeing nothing. of the attractive prospect on either side, and ignoring all invitations to tempt fortune by excursions into unknown regions, these restless spirits stand out as valuable exceptions. They play an important part in the economy of the art world, for they keep alive the love of experiment, and encourage that desire for progress which would soon die out if the popular inclination to bind all artists down, each to his particular pattern, were generally accepted.

Silver Bonbonière.

Therefore to every one who thinks carefully and deeply about aesthetic questions there is no more fascinating subject for study than the methods employed” by the all-round man in working out the problems presented” by his profession. He has always something fresh to say, some new hint to give about old ideas; and the suggestions he has to offer are constantly worthy of consideration, because they open up wider possibilities of practice and make for a better grasp of artistic essentials. By watching the various stages of his progress an excellent idea can be gained of the comprehensiveness of art in the broad sense and of the multiplicity of opportunities that are open to the intelligent student of great principles. Every new departure he attempts, every fresh experiment in methods or processes, has its value as a demonstration of the opinion of a thinker who is not ashamed of his insatiable curiosity and has no hesitation in setting [75/76] before other people the visible proofs of his never ending speculations. The wider the ground he covers the more important the lesson he has to teach, and the more significant is the display of his personality. If he carries his investigations to their logical extreme and alternates between painting, sculpture, design, and those other forms of craftsmanship that call for sound appreciation of practical details, he provides what is actually a personal commentary on the art opportunities of his time, and throws the light of his own individuality upon the many phases of artistic belief. He shows us, indeed, how in the mind of one careful thinker the whole range of aesthetic opportunity can be analysed, and how each special device can be employed to give the right expression to each one of his intentions.

Left: Electric light holder and shade. Right: Fireplace.

It would, perhaps, be difficult to find a more instructive instance of the unrest of a nature dominated” by the craving for a mastery over artistic methods than is provided by the career of Mr. W. Reynolds-Stephens. His experiences serve as a kind of object lesson in versatility, and illustrate effectively the resource of a man whose ambitions are not narrowed down” by considerations of commercial expediency. Nothing akin to specialism plays any part in the policy of his working life. No idea of making himself a popular favourite” by constant repetition of the same formula, and” by harping so persistently on a single string that at last he could gain recognition as the one exponent of a particular harmony, has ever perverted the sincerity of his professional effort. All roads seem to him to be worth following if only they lead to a goal important enough to justify the expenditure of energy necessary for reaching it. He finds his greatest pleasure in change of direction and in variety of performance, not because an unstable conviction urges him to be constantly running after new fancies, but because he realises that there is no type of production which is hot worthy of the attention of an artist who has sufficient judgment to draw the right distinction between effective triviality and sterling aestheticism. The commonplaces of art do not attract him, for they offer him no scope for invention, and the hum-drum routine of the profession is distasteful because it leads at best to merely mechanical proficiency without vitality or originality. What he wants is room to expand; and if, as he enlarges his borders, he can make new discoveries, he grudges none of the labour needed for turning them to full account.

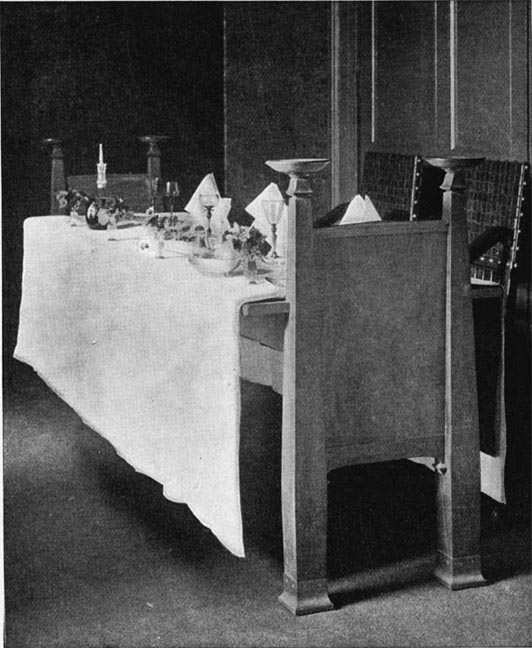

Left: Briar Rose. Right: Dining-Table.

This anxiety to make himself independent of fashions in art was a very evident feature even of [76/77/78] his student life. His course of training was marked by the same desire for comprehensive knowledge that has controlled the entire course of his mature practice. He was born, in 1862, in Canada, but left that part of the world in very early childhood, and was educated in England and Germdny. Like so many other men who have taken high rank in the artistic profession he was destined for a very different career, and his boyhood was passed in pursuits quite unlike those which he has since adopted. The particular vocation for which he was considered to be fitted was engineering, doubtless because he gave evidence even then of that constructive sense which has played since a part of great importance in his art work; and until he reached the age of twenty years the possibility of any change in his occupation was not contemplated. But then his craving to become an artist proved irresistible; and, despite his prospects of success as an engineer, he abandoned a post of some considerable value to launch himself upon the sea of troubles which is popularly supposed to be always ready to engulf the aspirant for artistic fame,

Left: Nineteenth-century Worship of Christ, an altar frontal.

From 1884 to 1887 he was a student in the Royal Academy Schools, and while there he made it quite clear that lack neither of capacity nor industry would stand in the way of his progress in after life. During these three years he distinguished himself” by taking the Landseer Scholarship for sculpture, and prizes for a set of figures modelled from life, and a model of a design, as well as another award, in painting, for a design for the decoration of a public building. This decoration he was, in accordance with the custom of the Academy, commissioned to carry out in a permanent form. The place selected for it was a wall-panel in the refreshment room at Burlington House, iind, as events have proved, the choice was a most unfortunate one." The space which was allotted to the young artist is so situated that any kind of painting applied to it is doomed inevitably to destruction. Through the wall itself passes the flue from the kitchens beneath the refreshment room, immediately below the panel is a large coil of hot-water pipes, and on either side of it are two large ventilators. Obviously, any mural decoration exposed to the changes of temperature unavoidable with such surroundings, and raked constantly” by blasts of hot air laden with London dust, would soon cease to be anything but a grimy caricature; and this piece of work, though Mr. Reynolds-Stephens completed it so recently as 1890, has already become a ghost of its former self. It has had to be cleaned so often and so violently that what remains of it now is only the preparatory under painting, and as time goes on more dust and more cleansing will probably remove even these lower strata of the picture and leave the wall once more a surface of bare plaster. That this would be the fate of his design he pointed out to the Council of the Academy, and he received from them a promise that steps should be taken to amend matters, but this promise has never been fulfilled.

Summer by W. Reynold-Stephens.

The first appearance of Mr. Reynold-Stephens as an exhibitor in the Academy galleries was made in 1885, while he was still a student in the schools, His contribution, which began a series that has continued without a break until the present time, was a water-colour drawing, A Valley near the Sea; but it” by no means foreshadowed any devotion on his part to the particular class of art which it represented. Indeed in 1887 he appeared not as a painter but a sculptor, for he exhibited a statuette, Pigeons; and although another water-colour drawing, Summer, was hung in the following year, sculpture again occupied him in 1889, when his chief works were a high relief, Truth and Justice, and a low relief, The Women of Amphissa, an adaptation in the form of a long frieze from the picture” by Mr. Alma Tadema, for whose studio the work was executed. A wall fountain showed in 1890 his inventive power and his skill in the application of decorative principles; and then for [78/79/80] five years he set himself to establish his reputation as an oil painter. He exhibited in succession four great allegorical compositions, Summer, Pleasure, Love and Fate, and In the Arms of Morpheus, splendid designs stated with superlative vigour, and marked” by exquisite qualities of line and colour arrangement. They put him at once among the few modem artists who have a true appreciation of the possibilities of pictorial decoration, and they revealed him as the possessor not only of extraordinary capacities as a draughtsman, and a singularly acute sense of technical subtleties, but also as a colourist who could carry out complicated harmonies without mannerism or half-hearted compromise. He found another direction in 1895 for his Academy picture that year was a portrait; and then in the following spring he returned to sculpture and exhibited a small bas-relief, Happy in Beauty, Life and Love, and Everything.

Left: Happy in Beauty, Life and Love, and Everything.

Right: Sleeping Beauty.

Since then he has sent to the Academy no pictures, but has confined himself to modelled work of various kinds. Even in sculpture he plays upon the many forms of expression of which the art is capable, and is ready to treat it in any way” by which he can gain effects unlike those at which he has already arrived. For instance, in 1897, he produced an exquisite little piece of silver work, a bon-bon dish, which was worthy of a place among the best examples of a craft that has never lacked eminent followers; and in the same exhibition in which this dainty trifle was placed he showed bronze panel — The Sleeping Beauty — that was purely an achievement in modelling according to the best traditions. In both contributions his complete understanding of appropriate technicalities was indisputable, and there was no sign of failure on his part to draw the right distinction between the methods applicable to each type of production. The bronze bas-relief suffered, how ever, from the conditions under which it was shown at the Academy. Planned as it was expressly to fill a space over a chimneypiece, of which it was an essential part, reason demanded that it should not be separated from its setting, and so it was sent up for exhibition fitted into a model of the chimney-piece itself, which had been designed by Mr. Norman Shaw. But the Council in its wisdom decided that the model was inadmissible, and required that the panel should be detached and hung upon the gallery wall without any setting whatever. Of course the effect of this indefensible revision of the artist's intention was to rob his work of half its meaning, and to make its particular character barely intelligible, but as the autocrats at Burlington House offered him no alternative between the mutilation of his design and its exclusion from the show he had to accept the position.

Sir Lancelot and the Nestling.

But in the course of [80/81/82/83] another year he hardened his heart and prepared for the Academy a fresh illustration of his theories about the necessity for an intimate connection between a work of art and its setting, forming at the same time a resolution that he would be represented in the exhibition” by nothing but the complete expression of his ideas. What he chose as a subject for the exercise of his ingenuity was a piece of furniture designed for the display, under proper conditions, of the small bronze panel which he had exhibited in 1896. He constructed a stand of carved wood, a column with a revolving top, and carrying a swing arrangement which would admit of the relief being adjusted at any angle that might allow it to be seen to advantage in a room with ordinary lighting. This stand, with its enrichments in bronze and copper, was a decorative object of very considerable beauty, as well as an excellently devised piece of construction, possessing in high degree the artistic quality of fitness for its destined purpose; and fortunately its right to consideration as a complete achievement proved great enough to convince the Academy authorities. The artist, however, has not this Spring thrown any strain upon the prejudices of the Council, for what he has contributed to the show at Burlington House, a statuette of Sir Lancelot and the Nestling, not in any way opposed to the traditions of the place, although it is, at the same time, a very worthy example of craftsmanship and of remarkable quality as an exercise in the technicalities of metal working.

Cushion in appliqué-work.

To study the craftsmanship of Mr. Reynolds-Stephens it is, however, best to turn to his many achievements that have appeared in the Arts and Crafts Exhibitions, and to examine the specimens of domestic and ecclesiastical decoration which he has provided in many places. From these an even more suggestive insight into his variety of resource can be obtained than from the list of Academy works with their contrasts of method and subject. They show him not only as an executant who has mastered the most intimate details of his profession and has the judgment to apply them each in the right way, but they also reveal the fertility of his mind and the wide range of his imaginative faculties. In his love of symbolism and the use he makes of explanatory emblems in his designs is seen his love of poetic imagery, impelling him to carry to completeness his mental inventions with the same minute care that he bestows upon the perfecting of the tangible object to which his hand gives form.

No better instance of this combination of qualities could be quoted than the mantelpiece which he has created as a setting for his picture Summer. Every part of this piece of work has its particular appropriateness and explains some part of his intention. The motive of the picture is suggested in the floral forms introduced in the moulding of the mantelshelf, the roses typify the light of summer, the poppies drowsy heat, the sweet pea the fragrance of the air; while below the details of the fireplace have their special significance, emphasising the sacredness of the hearth and pointing the meaning of the motto adopted, " Here build with human thoughts a shrine." The canopy over the grate is introduced as a symbol of shelter, beneath which men may meet for thoughtful conversation, the little trees each springing from a heart are emblems of thought issuing from hearts cheered to open” by the warmth of the fire, and the standards supporting the canopy are formed in the shape of a St. [83/84/85] George's cross, to point the situation of the hearth in an English home. In everything he does there is the same earnestness, and whether he is engaged upon a decorative adjunct to a modern house like his other mantelpiece with the Sleeping Beauty panel, or a piece of church furniture like his altar frontal, or upon a stained-glass window, he is always consistent in his manner of working. His designs become, as it were, arguments, didactic in their purpose, and with a sort of literary undercurrent that gives them an almost dramatic meaning. Each one provides food for thought and appeals as definitely to the intellectual faculties of the people who examine them as to their aesthetic instincts. He gives nothing which he has not thought out, and suggests no idea that he has not analysed and tested” by the light of reason. Yet his symbolism is in no way restless or self-assertive, and is scholarly without being ponderous. It adds to his art an air of elegant completeness, perfecting it, and rounding it off with a subtle touch of harmony; and it never goes astray in the direction of merely purposeless imagery. That it should be so admirably balanced and yet so rich in its variety, is its completest justification.

Bibliography

"The Work of W. Reynolds-Stephens." The Studio. 17 (1899): 74-84.

Last modified 22 April 2007