noch Bassett Keeling (1837-1886) was born into the family of a Wesleyan minister in Sunderland, and had his architectural training in Leeds. Then, like so many ambitious young architects, he gravitated towards London. This was in the later 1850s. Along with Edward Buckton Lamb, Samuel Sanders Teulon and a few others, he is classed as one of the rogue architects of the period, whose idiosyncratic designs seemed designed to surprise by their excess rather than please by their harmony.

Keeling was a controversial figure at the time. The architect J.P. Seddon,for instance, was reported in the Building News of 8 February 1867 to have seen him as an example of those who used "meretricious forms to arrest the gaze of the uneducated eye" (102). A few months later, E.W. Welby (Pugin's eldest son) was complaining in the same journal that both he and Keeling had been attacked in one of its reviews — Keeling for what Pugin himself considered to be his "vivacious and original conceptions" (502). Pugin's support was uncommon, and speaks well of him, but criticism of Keeling's work by the architectural establishment continued. One early twentieth-century architectural historian, Basil Clarke, considered his churches to be a "caricature of everything that was worst in the foreign Gothic craze" (158). Clarke's reference to "foreign Gothic" indicates the influence on Keeling of Viollet-le-Duc and also the kind of Venetian Gothic popularised by John Ruskin's The Stones of Venice, published in the early 1850s just when Keeling's career was taking off. To be influenced in these ways was not at all unusual at the time. But he and several other "Goths" still came under fire for adopting continental elements.

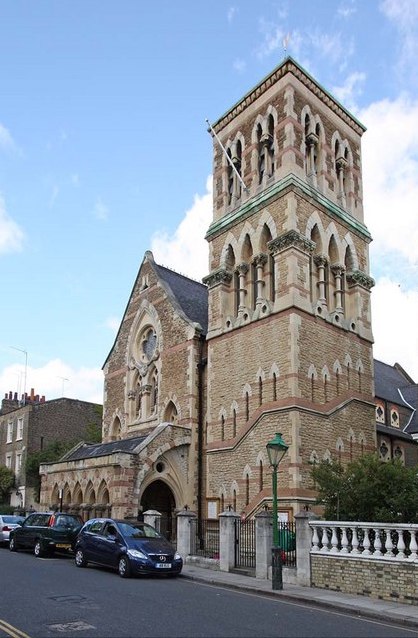

St George's, Campden Hill, Kensington

In our own times, James Stevens Curl specifies some of these elements, writing that "Keeling and Lamb, especially, designed churches for the Evangelical persuasion (and it shows): they both expressed roof-structures in an outlandish, restless way, seeming to want to jar the eye with repetitive notchings, chamferings, and scissor-shaped trusses. Their almost frantic originality, debauched Gothic, harsh, barbaric polychromy, and elephantine compositions brought critical wrath (notably from Ecclesiological quarters) down on their heads." Yet, as the younger Pugin's remark suggests, and as Curl himself writes elsewhere in collaboration with John Sambrook, "not everyone was against him or his work" (307).

Indeed, if ever there was a case for reassessment, this is one. But, unfortunately, it is especially hard to evaluate Keeling's output now. Edmund Harris, in a recent book on Keeling and those with whom he is grouped, explains:

Only four churches by him survive and none is fully representative of his intentions in its current state. St George’s, Campden Hill, St Andrew’s, Glengall Road, and Christ Church, Old Kent Road, have all been mutilated, with large sections of fabric removed, fittings replaced and decorative schemes painted out — the results, variously, of changing taste, structural problems, war damage and redundancy. St Andrew’s and St Philip’s, Kensal New Town, St John’s, Greenhill, and St Paul’s, Stratford, disappeared almost unrecorded, a combination of bad luck and 20th-century indifference to High Victorianism. By contrast, by the 1970s St Mark’s, Notting Hill and St Paul’s, Upper Norwood had come to be recognised as significant buildings by an important designer, and both were studied at length by James Stevens Curl, but this did not save them from demolition. Though St John’s in Killingworth avoided all of these misfortunes, it lacks its intended north aisle and tower, and in any case never quite stood comparison with the others. In almost all cases, the lost churches are known to us only by contemporary woodcuts or black and white archive photographs. [89-90]

Such illustrations, of course, preclude any true appreciation of Keeling's work, which makes part of its impact from polychromatic effects, for example, the use of blue and black Bath stone together. What a sad state of affairs!

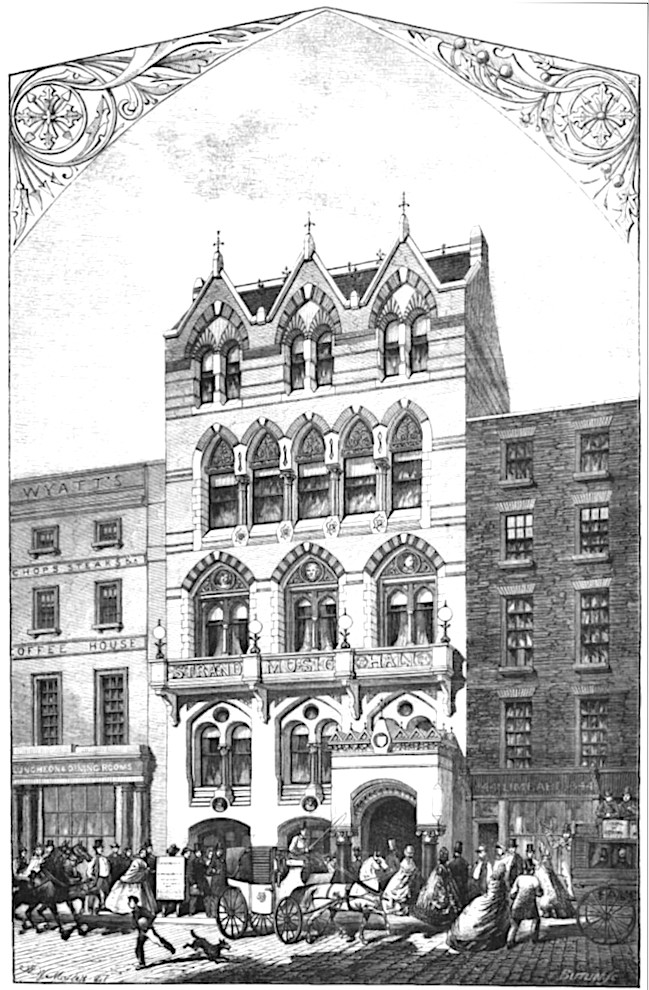

The old Strand Music Hall.

Sad, too, was Keeling's early death. His most notable work was not ecclesiastical: unusually for an architect in this kind of idiosyncratic Gothic style, it was a playhouse, the Strand Music Hall. Centrally located in a popular area, this made a strong statement and provoked a storm of criticism: "His Music Hall in the Strand was the talking point of 1864: ‘Acrobatic Gothic,’ in the jargon of the day. Anglo-Venetian and Early French were were his starting points. But excess seems to have become his basic principle, and vulgarity - in colour, material and form - his besetting vice," writes J. Mordaunt Crook, although he quotes Keeling's defence, too, that he had never aimed at "tenderness and delicacy," but rather at "general picturesqueness, and in detail piquancy and crispness" (137). Tragically, not only did this self-justification fall on deaf ears, but the playhouse's productions failed to please the authorities: "The Strand Music Hall seems doomed," ran the leading item in the Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review on 21 April 1866. "No sooner is one difficulty overcome than another springs up" — in this case, the "Holborn justices" were refusing to license it because of the frivolous nature of the shows (225). Despite the support it received from this magazine, the Music Hall's end was near, and Keeling's investment in it was lost, to the extent that he became bankrupt at the beginning of 1865.

After a brief "renaissance" of his career at the end of the next decade (Harris 128), when, for example, he designed 16 Tokenhouse Yard in the City, a further blow fell in December 1882, with the death of his wife in childbirth, followed less than eighteen months later by the death of the baby, his fourth son. The disappointed architect, who had always enjoyed socialising, increasingly took refuge in drink and died from liver disease before he turned 50 — a very sad end for someone who was undoubtedly able and ambitious, with ideas of his own and the courage to test boundaries by implementing them.

The Music (or Musick) Hall was the first of Keeling's works to disappear: it was replaced by the Gaiety Theatre as early as 1868. This did retain much of the original façade, but then the old Gaiety itself was demolished in 1903.

Despite such losses, Harris's book does help to give Keeling the credit he deserves for his originality and vigorous individuality. As a footnote, it is worth wondering how two other strikingly individualistic architects of the period, William Butterfield and William Burges, have escaped being classified as "Rogues." As for the former, he was indeed once included amongst them, and even seen as the most prominent of them (see Rogue Architects). But the category has been narrowed down over the years and Butterfield's distinctive genius has set him apart from them. He and Burges both expressed themselves with a keen eye for artistic unity and beauty, and with unmistakeable intensity of feeling — whether from deep religious commitment, in the case of Butterfield, or from natural exuberance, in the case of Burges. Completely escaping association with what Burges himself so damningly termed "the Original and Ugly School" (582), the latter is seen to represent instead, to borrow from the title of Crook's well-known book on him, "the High Victorian dream." Keeling might have had stood a chance of emerging from the "Rogue Gothic" category too, had a larger body of his work been preserved for posterity. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Architectural Works

- St Andrew's Church, Camberwell

- St John's, Greenhill, Harrow

- St George's, Aubrey Walk, Kensington

- The Strand Music Hall

- 16 Tokenhouse Yard

Bibliography

"Acrobatic Lecturing." The Building News Vol. 14 (8 February 1867): 102. Google Books. Free ebook.

Burges, William. "Art and Religion." The Church and the World: Essays on Questions of the Day in 1868, edited by Orby Shipley. London: Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer, 1868. 574-597. Internet Archive, from the library of Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad. Web. 30 March 2025.

Clarke, Basil F.L. Church Builders of the Nineteenth Century: A Study of the Gothic Revival in England. 1938. 2nd ed. New York: A.M. Kelley, 1969.

Crook, J. Mordaunt. The Dilemma of Style: Architectural Ideas from the Picturesque to the Post-Modern. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Curl, James Stevens. "Going Rogue: An interesting if unappealingly illustrated reassessment of a neglected style" (a review of Harris's book) The Critic. Web. 30 March 2025. https://thecritic.co.uk/going-rogue/

Curl, James Stevens, and John Sambrook. “E. Bassett Keeling: A Postscript.” Architectural History 42 (1999): 307–15. Jstor (institutional access). https://doi.org/10.2307/1568716.

"The Gaiety Theatre, Aldwych, Strand, London Formerly - The Strand Musick Hall." Arthur Lloyd.co.uk. Web. 30 March 2025. http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/GaietyTheatreLondon.htm#strand

Harris, Edmund. "Less Eminent Victorians." Web. 31 March 2025. https://lesseminentvictorians.com/author/edmundlouischarlesharris/

Harris, Edmund. The Rogue Goths: R.L. Roumieu, Joseph Peacock and Bassett Keeling. Swindon: Liverpool University Press for Historic England, 2024.

"London Commercial Buildings." The Builder Vol. 39 (14 August 1880): 215. Google Books. Free ebook.

Pugin, E. Welby. Correspondence. The Building News Vol. 14 (19 July 1867): 502. Google Books. Free ebook.

"The Royal Academy Exhibition" (the review in which Keeling is lambasted). span class="periodical">The Building News Vol. 14 (17 May 1867): 502. Google Books. Free ebook.

"The Strand Music Hall." Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, 1862-1870. 21 April 1866: 225. Internet Archive. Web. 30 March 2025.

Created 31 March 2015