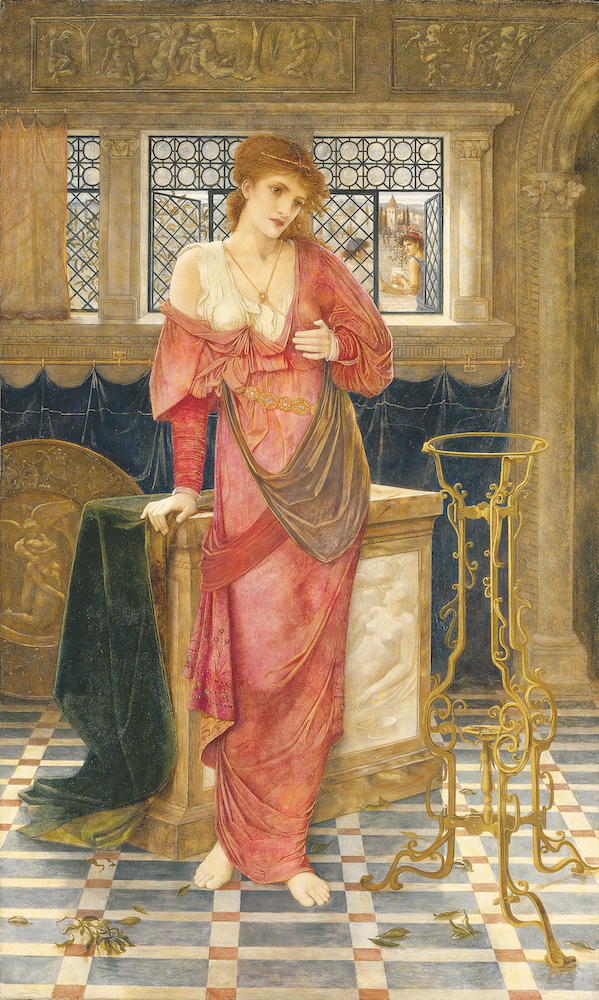

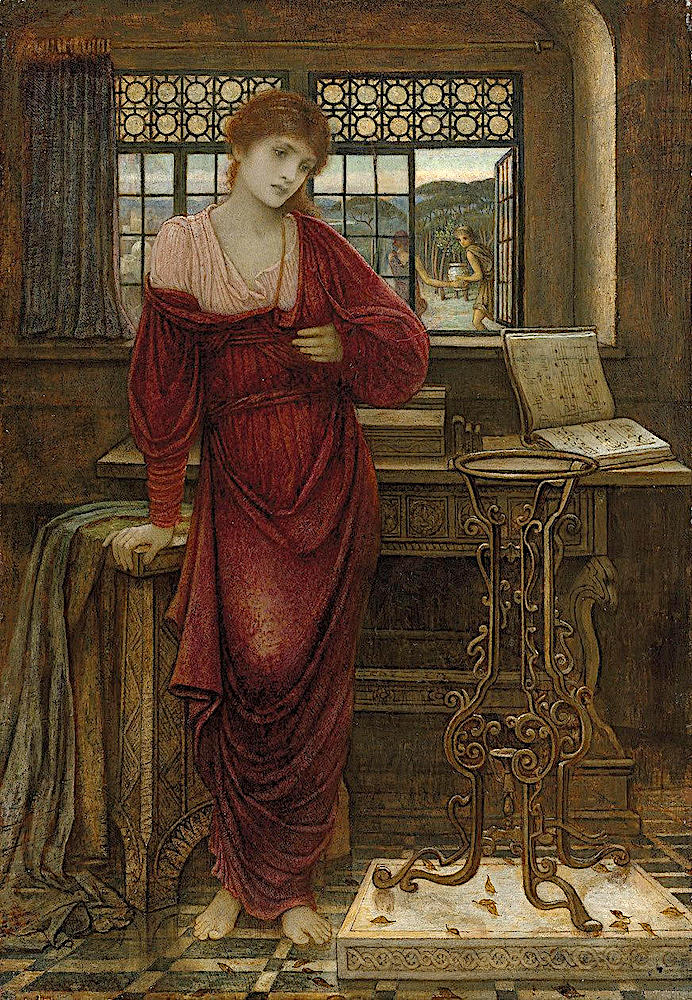

Isabella by John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937). Left: 1879 version. Oil with gold paint on canvas. 39¼ x 24 inches (99.7 x 61 cm). Right: 1886 version. Oil on board. 12 1/4 x 9 1/8 in. (31.1 x 23.2 cm.). Both versions in private collections. Images courtesy of Christie's, London, and not to be reproduced; the right click has been disabled.

With this work Strudwick has moved away from his previous Symbolist works and painted a more usual subject for the Pre-Raphaelites, one taken from English literature. Isabella exists in two versions. The principal version (on the left above) was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1879, no. 40, while a smaller version (reproduced on its right) was shown at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1886, no. 71. The principal version initially belonged to artist and aesthete W. Graham Roberston. It was widely exhibited, including at the Irish International Exhibition in Dublin in 1907 and the International Fine Arts Exhibition in Rome in 1911. More recently it was included in such prominent exhibitions as The Last Romantics held at the Barbican Art Gallery in London in 1989, Pintura Victoriana: De Turner a Whistler held in Munich at the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, in Madrid at the Museo del Prado in 1993, and at The Grosvenor Gallery: A Palace of Art in Victorian England held at the Yale Centre for British Art in New Haven CT and the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1996.

The subject of the painting is taken from the well-known poem by John Keats Isabella; or, The Pot of Basil. The poem, in turn, was derived from one of the tales in Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron. A couplet from Keats's poem was included in the Grosvenor catalogue:

Piteous she look'd on dead and senseless things,

Asking for her lost basil piteously [sic];

In the quotation, however, the word "amorously" that was supposed to be at the end of the second line had erroneously been changed to "piteously." The story takes place in mediaeval Florence where Isabella falls in love with Lorenzo, one of her brothers' employees. The brothers are unhappy about this relationship, however, as they had planned to marry her to "some high noble and his olive trees." The brothers therefore murder Lorenzo and bury his body in a forest telling Isabella he has been sent away on urgent business. Lorenzo's ghost, however, appears to Isabella in a dream and reveals his true fate. Isabella exhumes his body and cuts off his head, which she places in a pot of basil. She tends the pot obsessively, watering it with her tears. The brothers learn of this, steal the pot, and Isabella slowly pines away and dies of a broken heart. Strudwick's picture shows the anguished Isabella staring at the empty stand from which her brothers have removed the pot of basil. In the detail of the 1879 version shown on the right, the wicked brothers, carrying the pot away, are visible through the window.

The story fascinated the Pre-Raphaelites and their associates. In 1848, prior even to the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, D. G. Rossetti had proposed eight subjects from "Isabella" to be drawn by members of the Cyclographic Society. Millais first submission to the Royal Academy as a member of the P.R.B. in 1849 was Isabella. Millais' picture portrays an early incident in the poem with Isabella, Lorenzo and her brothers all seated at table. Lorenzo offers Isabella a blood-orange while staring at her intensely. George Frederick Watts had exhibited an Isabella e Lorenzo at the Royal Academy of 1840 and another Isabella in 1859. D.G. Rossetti made a drawing, The Pot of Basil, but this was never worked up into a painting. William Holman Hunt's Isabella and the Pot of Basil, showing Isabella standing with her arms around the pot of basil, dates from 1866-68, and he painted a smaller version of this same subject in 1866-67. Simeon Solomon drew versions of Lorenzo and Isabella, Isabella, Isabella with the Head of Lorenzo, and Isabella with the Basil Pot. J.W. Waterhouse's Isabella and the Pot of Basil, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1907, shows Isabella kneeling and clutching the garden pot where Lorenzo's head is buried. The subject of Keats's poem thus continued to attract painters even into the beginning of the twentieth century. Strudwick would undoubtedly have known the compositions by both Millais and Hunt.

The central part of both of Strudwick's compositions remains much the same, but the versions vary in significant details, showing that the second picture was not merely a copy of the first. In both versions Isabella is shown standing in her chamber with her left hand held over her heart. She has a more anguished expression on her face in the second version. An elaborate wrought-iron stand is shown to her left upon which the pot of basil containing Lorenzo's head recently stood. The floor is strewn with basil leaves. Through the window at the rear of the room her two brothers can be seen stealing away with the pot. More of the brothers' bodies are visualized in the second version and the landscape in the background, as visualized through the window, differs markedly in the two versions. The models for Isabella and her hairstyle, costume and jewelry differ conspicuously between the two versions and the room in which she resides differs markedly in terms of their furnishings and decoration as well.

John Christian has pointed out the differences in handling of the details in this picture as depicted by Strudwick in contrast to those in the paintings by Millais and Hunt:

It was typical of Strudwick to hint at drama rather than making it explicit. No artist was ever less endowed with the dramatic gift. His talent lay almost exclusively in portraying wistful, love-lorn maidens in spaces pervaded by Aesthetic shadows and so encrusted with gem-like surfaces as to suggest that a jeweller has been the interior decorator. Isabella's chamber is typical, and so is the imagery of the marble or bronze reliefs. The more robust Millais and Hunt had employed a whole range of symbols to emphasise the horrific nature of the story. Millais not only goes in for blood-oranges and brutalised dogs but a majolica plate painted with a scene of execution by beheading and a hawk tearing up a white feather. Hunt gives Isabella's pot death's-head handles to suggest its grisly contents. Strudwick's reliefs, by contrast, seem to show only playful amorini and two scenes which hint vaguely at the story of Cupid and Psyche. This subject, which Burne-Jones had treated in the mid 1860s in his illustrations to Morris's Earthly Paradise, would indeed be appropriate in that Psyche loses Cupid, her celestial lover. However, she also regains him after many trials and tribulations. Was Strudwick being true to his gentle vision by opting for a story with a happy ending, or was he suggesting that Lorenzo and Isabella would also be re-united in death?

Contemporary Reviews of the Principal Version

The picture was again well received by the critics. Joseph Comyns Carr in The Academy praised its poetical fancy while expressing concerns over Strudwick's figure draughtsmanship:

Isabella (No. 40) of Mr. Strudwick, an artist who brings a system of highly-wrought and delicate workmanship to the rendering of ideas that are far removed from contact with the passing life of our time. Mr. Strudwick has always been inspired by a fine poetical fancy, and his present performance shows that he is rapidly gaining the resource and power needed to do full justice to his ideas. There is still something to desire in the drawing of the figure; but all the subordinate parts of the design are expressed with the utmost care and patience, and with a sureness of touch that is worthy of the poet whose verse he has shriven to illustrate. [441]

A reviewer for The Architect found the work beautiful in both arrangement and design:

Mr. Strudwick may be said to have made his first appeal to the public in the Grosvenor Gallery, and the notice his work then excited should be justified by the two pictures of this season, a subject from Solomon's Song (35) and Isabella (40) of Keats.... The Isabella is far more satisfactory, and in arrangement of colour and design is very beautiful. The figure of Isabella supporting herself by her hands against a table, and 'piteously' contemplating the empty tripod from where the pot of basil with its ghastly contents has been removed, is full of mournful grace; the face with its haunting eyes and soft pale curves point above the folds of raspberry rose, drapery, and is the focus of the picture. The artist has shown his skill in subordinating to the principal figure all the background and accessories, detailed as they are with change of blue and grey marbles, window of greenish quarries, through the open casement of which are seen dainty figures of women in bright dresses, and the gleam of stately buildings. The whole scheme of colour is peculiar and beautiful, and there is a completeness about the entire work which seems to us more significant of power than the charming symbolic "inventions" which first drew remark to Mr. Strudwick's name. It is, however, difficult to distinguish between the result of labour in a poetic school under careful training and the outcome of independent genius. Time will doubtless test this artist's power to stand alone. [276]

F.G. Stephens in The Athenaeum praised both the execution and the colour of the picture:

We turn to Mr. Strudwick's Isabella (40) with pleasure, which would be unalloyed if the artist, instead of appearing to glance at Mr. Rossetti, or to adopt the exaggerated cultus of Mantegna that is now fashionable, had discarded affectations which can only be temporary. Keats's Isabella asking for her lost Basil piteously is represented by a wan and wasted maiden standing before the tripod from which the tragic vase has been removed. Her face has a 'dazed' and hopeless look, which ought to distinguish the picture in the galllery as one surpassed in inspiration by no example here, except, perhaps, by Mr. Burne-Jones's virgin in the Annunciation.The attitude of Isabella is hardly, if at all, inferior to her face. The careful execution of the picture throughout is highly creditable to Mr. Strudwick. There are many excellent points of local colour, such as the deep red rose of the dress, while the painting of the accessories and floor, the window and furniture, is capital. The careful studies which this picture displays are exceptional in these careless times. [607]

The Builder noticed that in the painting Strudwick had moved away from his usual early Renaissance sources of inspiration: "Mr. Strudwick on having given up imitating early Italian masters [has] painted a picture with a certain beauty of its own, though it is not Keats's Isabella, but a lady of the modern artists' favourite type, with the usual red hair and long chin" (535). The Illustrated London News linked Strudwick's Isabella with works by other second-generation Pre-Raphaelite painters like Marie Stillman, Evelyn Pickering [De Morgan], and Charles Fairfax Murray. It is therefore interesting to read what a conservative critic felt about this group as a whole: "Our readers are acquainted with the characteristics of the painters we refer to. Some copy more or less the old masters; too many are content to copy other copyists, when we have, of course, the blind leading the blind. Scarcely any affectation is too shallow or too morbid to find imitators; till a sort of cultus is promulgated for the indiscriminate worship of the results, mainly of neglected training, or the products of sheer imbecility, and appropriately enough the faith is protected by a band of amateur critics" (567).

Contemporary Reviews of the Second Version

When the works Strudwick sent to the Grosvenor Gallery in 1886 were discussed most coverage was given to his Circe and Scylla rather than to a version of a painting previously exhibited. Only the critic of The Times, likely Harry Quilter, preferred Isabella of the two works Strudwick contributed: "Mr. Strudwick, the ablest of the followers of Mr. Burne-Jones, has made a considerable advance on any of his former works, both in Circe and Scylla and in the smaller and perhaps more desirable picture of Isabella (651).

Other depictions of "Isabella and the Pot of Basil" and related subjects

- Strudwick's figure study for Isabella and the Pot of Basil (1879)

- William Holman Hunt's Isabella and the Pot of Basil (painting, 1867)

- Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale's Isabella and the Pot of Basil (drawing, c. 1898)

- Henry Charles Fehr's Isabella and the Pot of Basil (sculpture, 1904)

- Edward Reginald Frampton's Isabella and the Pot of Basil (painting, 1867)

- John William Waterhouse's Isabella and the Pot of Basil (painting, 1897)

- Frederic Sandys's Until Her Death (woodcut, 1862)

Bibliography

Blackburn, Henry. Grosvenor Notes. London: Chatto & Windus, 1879. 18.

Carr, Joseph Comyns. "Grosvenor Gallery." The Academy XV (May 17, 1879): 441-42.

Christian, John. The Last Romantics. The Romantic Tradition in British Art. London: Lund Humphries, 1989, cat. 44, 92.

Christian, John. The Pre-Raphaelites and Their Times. Tokyo: Isetan Museum of Art, 1985, cat. 30, 72-74.

Christian, John. Important British & Irish Art. London: Christie's (November 28, 2001): lot 2, 22-27. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-3827951

"The Grosvenor Gallery." The Builder XXXVII (May 17, 1879): 534-35.

"The Grosvenor Gallery." The Illustrated London News LXXIV (14 June 1879): 567.

Kolsteren, Steven. "The Pre-Raphaelite Art of John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937)." The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Studies I: 2 (Fall 1988): 11, nos. 7 and 15.

Quilter, Harry. "The Grosvenor Gallery." The Times (1 June 1886): 651.

Stevens, Frederic George. "The Grosvenor Gallery Exhibition." The AthenaeumNo. 2689, (10 May 1879): 606-08.

"Studies in the Grosvenor Gallery." The Architect XXI (10 May 1879): 275-76.

Victorian and British Impressionist Art. London: Christie's (May 31, 2012): lot 18, 30-31. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5563215

Created 5 October 2025