For the larger part of the nineteenth century, a much narrower meaning was generally implied by describing an English song as a 'national song' than might be presumed from an acquaintance with Boosey's National Song Book of 1906. Although the title 'national songs' or 'national airs' was commonly given to a collection containing a varied selection of songs of a single country (for example, Moore's Irish National Airs of 1818-28), when applied to English songs, the description 'national' tended to signify songs of patriotic sentiment rather than songs sharing the same ethnic quality. The notion of there being an Englishness in the musical character of a song which could be labelled 'national' did not gain wide currency until the 1890s. The English 'national song' and the search for an English national musical identity in song must be seen in the context of British imperialism.

If imperialism were to be defined solely as the formal annexation of territory, there would be an argument for regarding 1815—70 as an anti-imperialist era. Annexation did not altogether cease (the Falkland Islands, for example, were annexed in 1833), but mercantilism and colonialism were being challenged and forced to give way to laissez-faire and free trade. Lenin, however, who defined imperialism as a particular stage in the development of capitalism, argued that the enthusiasm for liberating the colonies (shown by some bourgeois politicians) sprang from thriving capitalist competition; but, as capitalism passed into the monopoly stage — as other countries industrialized, as companies became larger, and as the big banks increased their control as agents of finance capital - there came about an 'intensification of the struggle for the partitioning of the world'.1 Fear of losing markets was a stimulus to the 'conscious imperialism'2 or 'new imperialism' which was being articulated in the 1880s. Behind the 'scramble for Africa' lay a European economic crisis, though Conservative politicians talked of a 'civilizing mission' and 'imperial responsibility',3 and criticized Gladstone for not upholding British interests abroad (the death of General Gordon was constantly flung at him). With an air of inevitability, the Liberal Party itself witnessed its imperialist wing rapidly growing in strength during the later years of the century.

It is noticeable that songs written in the period of 'new imperialism' lay greater stress on Britain and things British than had been the norm earlier in the century, when a title like 'Britain's Glory', which was given to a 'National Song' of 1845, [169/170] was unusual. In later years, however, there appeared such songs as 'The Glory of Britain' (1876), 'Britain's Flag' (1888), and 'Britannia's Sons' (1893). These were followed by many others after the turn of the century which demonstrated an increasing fondness for waving the British flag and invoking Britannia. After the Napoleonic Wars and before the 1890s, patriotic songs were almost entirely concerned with England: examples are 'England, Europe's Glory' (c. 1859), 'England's Strength' (1860), 'England's Greatness Still Endures' (1864), and 'England's Heroes' (1880). All of these songs could have used 'Britain' in their titles with little change of meaning; England was Britain at this time. In the 1890s and later, however, the word 'England' tended to be preferred as part of a personal emotional appeal: this is epitomized by W. E. Henley's poem 'England, My England', which was set to music often in the early twentieth century. As part of a broad patriotic appeal, the word 'British' was better suited to the age of 'new imperialism' since it acted as a claim upon the loyalty of the Empire's subjects in its suggestion of a homogeneous British imperial unity.

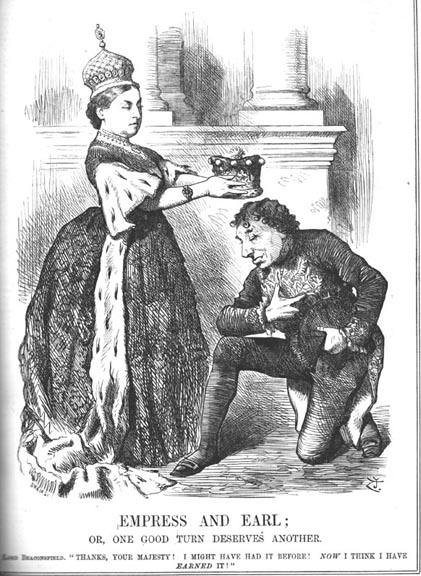

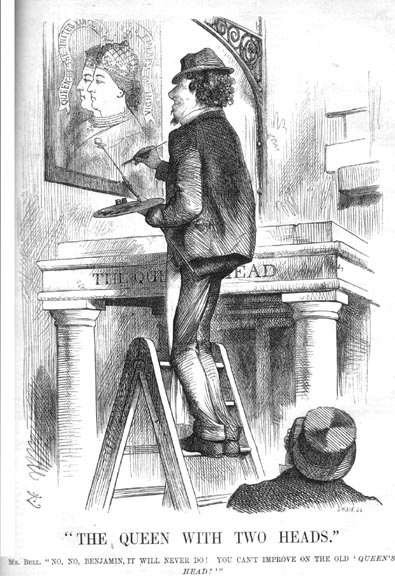

Three of John Tenniel's 1876 Punch cartoons about Disraeli and retitling Queen Victoria

as the Empress of India. Left to right: (a) New Crowns for Old Ones. (b) Empress

and Earl; or, One Good Turn Deserves Another. (c) The Queen with Two Heads.

[Not in original print edition.]

The crown of the United Kingdom became the symbol of imperial unity, particularly during and after the Jubilee of 1887 (though the idea may be traced to Disraeli and the conferring of the title 'Empress of India' upon Victoria in 1876). E. P. Thompson sees the Golden Jubilee as the inauguration of a 'modern' concept of royalty as a distracting pageant (1887 was a year of depression), with the monarchy as a focal point for orthodox herding instincts, jingoism, circuses, 'respectability', and guff.4 Even a music-hall publisher, Francis Bros. & Day, turned out a 'Song of Jubilee'. It was a sign of things to come; by 1900 another music-hall publisher, Hopwood & Crew, was offering a whole Navy and Army Patriotic Album. Songs in praise of Victoria were nothing new to the drawing-room ballad market, of course; and the idea of Victoria as Empress had been foreshadowed in song almost twenty years before she received that title — following the suppression of the Indian Mutiny in 1857, a 'new national anthem' was written by Edward Clare, entitled 'Victoria! Empress of the East'. In fact, there is much in the songs written at the time of Crimea and the Indian Mutiny to add weight to Gallagher and Robinson's 'continuity thesis',5 which holds that there was no aversion to empire building during this period, but that it lacked the strategic planning which came in the depression-dogged years of 1873-96.6 Gallagher and Robinson coined the phrase 'imperialism of free trade' and suggested that there was an 'informal empire' of places not formally ruled by Britain, yet dominated by Britain in some way. Colonial 'responsible governments', for example, may have enjoyed local autonomy but were still economically dependent on Britain; it was an idea hatched after the Canadian rebellions which successfully served to forestall a repetition of the American Revolution. If necessary, force was always ready to be used to protect the interests of free trade.

There were contradictions in the way formal and informal control was exercised: while internal self-government was being introduced in British North America in 1846, India was still being developed in a mercantilist way; only after the Mutiny did the British government rely on class collaboration from princes and magnates (the 'natural leaders' of the people) to ensure control. Gilbert and Sullivan's operetta Utopia Limited (1893) could be seen as a comic fantasy on the free trader's faded dream of informal control of a country by market forces; in this work, Utopia becomes the first country to be floated as a limited company. Before the dawn of the 'new imperialism', many songs shared the perspective of the free trader. Here is verse 3 of 'The Men of Merry England' (1858), a song written and composed by J. B. Geoghegan, published in an arrangement byJ. Blockley. The occasionally eccentric punctuation of the original has been maintained.

Oh! the men of merry, merry England,

Where'er Jove's thunders are hurled;

Bright monuments rise, of their enterprise,

And their commerce gives wealth to the world.

Still, may it increase, whilst the fair hands of peace

Shed plenty and blessin; so free,

Should war call again, our rights we'll maintain,

Then gaily my burthen shall be.

The men of merry, merry England, etc.

Sympathy can also be found for the pacifist wing of the Manchester School, led by Richard Cobden, which opposed the use of power in foreign policy. Here is the first verse of Henry Frank Lett's 'Song for the Peace Movement' (1849).

God knows with what a trumpet tongue we've boasted of our wars,

And set our Soldier-idols up and lauded gallant Tars,

And blown a loud defiant blast across each purple sea

But men of Peace have risen, and said, 'This shall no longer be,

For that fierce Lion carnage-clawed we'll from our flag remove,

And straight inscribe with olive branch a gentle milk-white Dove.

There is a clear distinction between the demand that the British flag be respected, which is voiced in a great number of songs during the period of 'imperialism of free trade', and the transparent aggression and covetousness found in eighteenth-century songs espousing the mercantilist cause, or late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century songs committed to the 'new imperialism'. Arthur Benson's well-known words, fitted to Elgar's music, in the refrain of 'Land of Hope and Glory' (1902), 'Wider still and wider shall thy bounds be set; /God, who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet.', show a return to the aspirations articulated in verse 5 of'Rule, Britannia':

To thee belongs the rural reign,

Thy cities shall with commerce shine,

All thine shall be the subject main

And ev'ry shore it circles thine.

There were times when enthusiasm for new patriotic songs waned (noticeably 1825-30, 1845-50, and 1865-70), but they were always ready to roll off the presses when the possibility of international hostility loomed on the horizon. Then, not only were new songs produced, but 'traditional' patriotic songs were dug out and revitalized: in 1851 'The British Grenadiers' was published in London as an individual sheet-music item, labelled 'National Song'; and at the outbreak of the Crimean War the publisher C. Jeffreys issued a new version to [171/172] which had been added extra verses of his own. Yet there is no record of this song having received the distinction of being published on its own since the 1770s.

When the Crimean War began in 1854, songs were being produced such as 'England! Empress of the Sea!', 'England's Queen to England's Heroes', and 'England's patriotic appeal to her sons against the Russian despot, To Arms!' The difference between the warmongering at the time of Crimea (1854-6) and that at the time of-the Russo-Turkish War (1877—79) was that the Conservatives made a conscious effort to involve the working class in imperialist sentiment during the latter.7 They wished to intervene in this war and, as part of their effort to whip up popular support, may have paid for the services of the music-hall entertainer, the 'Great Macdermott'.8 It was 'Macdermott's War Song',9 with its refrain beginning 'We don't want to fight, but by jingo if we do', which gave the word 'jingoism' to the English language. The success of this approach was evident when demonstrators smashed Gladstone's windows, and a previously vacillating Parliament was moved to vote £6,000,000 for military use (see Lee 101). With few exceptions, the songs published at the time of Crimea adopted a style more suited to the drawing room than the battlefield; even Captain J. Wilson's parody of 'Kelvin Grove' in 'Crimea's Battlefield' (1854), which begins, 'Oh! campaigning's no for you, bonnie lassie. Oh!', probably owes more to the fashionable enthusiasm for 'Scotch songs' in the 1850s than to any desire to acknowledge the part played by Scottish soldiers. A large number of men recruited to fight were actually Irish, and one of their songs which is still sung today is 'The Kerry Recruit';11 its gory detail and stoical humour are in strong contrast to the elevated patriotic sentiment favoured by the bourgeoisie.

Until Gerard F. Cobb's settings of Kipling's Barrack-Room Ballads in the early 1890s, there was an immense gulf between the fighting man as depicted in drawing-room ballads and the British Army soldier (for whom, in reality, there was widespread contempt both among the bourgeoisie and his own commanding officers). After Dibdin, vernacular speech was less commonly used, even in sailors' songs; that Cobb became known as 'the Dibdin of the Army' probably owed as much to the use of the vernacular in Kipling's verse as to the tunefulness of the music. Kipling's men speak in a markedly different manner from the eloquent belligerance of the soldiers and sailors of the early nineteenth century, such as were encountered in 'The Death of Nelson' (1811) and 'The Soldier' (1815) in Chapter 1. In the years following the Napoleonic Wars, these characters developed a tender side, as revealed in 'The Soldier's Tear' ofc. 1830 (words by T. H. Bayly, music by A. Lee), but not at the sacrifice of an ounce of courage, as is confirmed by 'Yes, Let Me Like a Soldier Fall', a favourite air from Wallace's Montana (1845). The Dragoons of Gilbert and Sullivan's Patience (1881) are not an unfair caricature of the type of martial characters met with in the drawing room up to that time. The growing interest in the thoughts and words of the ordinary fighting man, as mediated by middle-class poets and composers, may be related to the search for English identity during the age of 'new imperialism'- There was also, of course, a feeling that this sort of song would win cross-class appeal. The following are press comments concerning some of Cobb's settings of Barrack-Room Ballads: 'Sure to gain popularity, both in the mess-room and in the [172/173] barrack-room' (Madras Times, 28 September 1892). 'We have no hesitation in saying that these songs are bound to become popular throughout the entire British Army' (United Services Gazette, 13 August 1892).12 Nevertheless, their perceived market is middle class. It was the music-hall which remained the prime vehicle for winning workers over to the imperialist cause, right up to the outbreak of the First World War when recruiting was helped by Vesta Tilley singing 'The Army of To-Day's All Right'. Jingoism did not, however, find its base in any working-class movement, but, according to the Liberal critics of imperialism in the 1890s, J. A. Hobson and L. T. Hobhouse, in the 'villa Toryism' of the suburban middle and lower middle class (see also Porter 136-37). Suburbanization in the late nineteenth century was not unconnected to the construction of an English rural mythology which helped to build a new kind of nationalism, both aggressive and sentimental. England becomes the land of thatched cottages, red roses, and ripe corn. Although it lacks the rural images in its verse, 'Land of Hope and Glory' establishes the new musical style for patriotic songs. The nineteenth-century variety called for a booming masculine voice; the newer type aims to fill the heart with pride and the eyes with tears and, for that reason, allowing for gender stereotyping, is eminently suited to the female voice. Dame Clara Butt must have seemed to many the voice of the motherland personified. The last gasp of British imperialism as a 'popular' cause came with a song clothed in all the garments of English national identity which had been stitched up in the present century. Written in 1939, 'There'll Always Be an England' gives an assurance that England will always exist while there is a 'country lane' and a 'cottage small beside a field of grain'. Here is the pastoral ideal, not to be confused with the farm labourer's cottage and its tin bath and earth closet (living conditions still occasionally found in Yorkshire in the 1980s, let alone the 1930s). When the stirring call to action comes, Englishness is typically replaced by Britishness:

Red, white and blue, what does it mean to you?

Surely you're proud, shout it aloud, Britons awake!

The Empire too, we can depend on you,

Freedom remains, these are the chains nothing can break.

One way of asserting English identity was to project as imperial virtues such English bourgeois values as 'character' and 'duty'. In Kipling's 'The White Man's Burden', imperialism itself has become invested with a sense of duty. The ideology of the home was similarly magnified: England begins by offering shelter to a bourgeois conception of freedom, as in 'England, Freedom's Home' of 1848; stretches out in a global embrace, as in 'England, the Home of the World' (1872)a 'national song'. The word 'men', with its connotations of courage and firmness, also began to appear in titles of increasing grandeur: in 1877 came 'Men of England', a 'national song'; in 1894 came 'Men of Britain'; then, in 1915, came 'Men of Empire', written to the tune of 'Scots Wha Ha'e'. Songs in the later 'nineteenth century came to acknowledge that men were dying overseas. Verse 2 of'The Old Brigade' of 1881 (words by F. E. Weatherly, music by O. Barri) begins, 'Over the sea far away they lie, / Far from the land of their love;' and Weatherly pursues a similar vein of thought in verse 3 of'The Deathless Army' of (music by H. Trotère): [173/174]

Their bones may bleach 'neath an alien sky,

But their souls, I know, will never die,

They march in a deathless army

The formal design of 'The Deathless Army', with its middle section pondering the subject of death, and a triumphant apotheosis for its conclusion, was a prototype for many later ballads concerning the armed forces, well-known examples being 'The Trumpeter' (1904) and 'Shipmates o' Mine' (1913).

In the 1890s the image of the patriotic Englishman was built into the character that was being constructed of the 'typical' or 'traditional' Englishman. The threat posed by imperial federation to English national identity was met by attempts to recapture some imagined rural ideal, included in which was the belief that unadulterated English qualities could be found in songs collected in the countryside. These songs, like patriotic songs, were given the label 'national', and, helped by the mediations of bourgeois folksong collectors, an idea of a homogeneous nation was formed which obscured the class divisions within British society. In a paper delivered to the Royal Musical Association in 1891, F. Gilbert Webb defines 'nation' as 'a number of people having certain things in common, such as language, one form of government, etc.'14 and argues that 'Folk-song may fairly claim to be the vital principle in the music of all nation' (121). Having referred (in the next sentence) to folksongs as 'national songs', he later proclaims that 'the origin of all folk-music is the endeavour to perpetuate by forcible and picturesque means the glories of love and war' (122). Behind much of Webb's article lies the pseudo-science of race. Darwinian anthropology had reinforced the notion of there being distinct races, and the pseudo-science of phrenology also related to racial questions (the 'long-headed man' and the 'broad-headed man' who anciently inhabited the British Isles). Theories of race should be distinguished from those of ethnicity: the former allude to unchanging, hereditary factors, while the latter allude to cultural factors; members of the same ethnic group may or may not be members of the same race, yet still be bound by the same cultural ties. Webb uses folksong to confirm racial stereotyping. He notes with regard to the rhythmic device known as the 'Scotch snap' which is so commonly found in Scottish song:

[it] is the musical expression of great muscular strength allied with highly- developed nervous force — I mean rapidity of nervous action, or transmission of thought to the muscular mechanism, which proceeds from great determination of mind and quick decision. It is the language of relentless resolution, of a mind which once fixed on the acquisition of an object cares not what consequences may result to itself or others so long as the end in view is attained. These, I need hardly say, are the chief elements which form the characters of successful warriors and conquerors, such as the Kelts. [122]

A grand claim for a rhythm which may simply derive from the greater ease with which the Highland bagpipe plays uneven quavers. Even Webb's example of a song whose 'petulant, wayward character' derives from use of the 'Scotch snap' is ' 'Twas Within a Mile of Edinboro' Town', which, as has been noted in Chapter 1, happens to be by an Englishman, James Hook (from Norwich). Webb then discusses what he calls the 'English style of music' (meaning, presumably, a white Anglo-Saxon style): [174/175]

What is the character of the majority of ordinary Englishmen? A well-balanced mind which regards everything in an intensely practical light and which submits everything to the question: 'What good will that do to my pecuniary or social position?' We hate display. All extravagance of language, dress, and gesture; we look upon the impulsive man with suspicion and upon the exaggerator with disgust, and regard enthusiasm as dangerous; we fear to let ourselves 'go' lest we should excite ridicule; in a word, we lack 'passion' On the other hand, we are magnani- mous and chivalrous, whether the object be worthy or no; emotional on social subjects, patriotic, and home-loving. What should be the music of such a people? Just what it is; good, honest, bold, straightforward strains, rich in melody, and breathing strong, healthy, human affection or simple-hearted gaiety, but innocent alike of exaggerated sentimentality, intellectual subtleties, or maddening mysticism. [125]

The novelty of Webb's application of racial theory to music in 1891 is shown by someone remarking in the course of the discussion which followed Webb's paper, 'I am very glad that someone has had the courage to stand up and assert the claims of national music to be regarded as the outcome of a people's feelings . . . The matter has never been thoroughly gone into' (133). Webb's views occasionally reveal the influence of racist ideas which grew apace as an adjunct of the 'new imperialism', when 'the ideology of Anglo-Saxon supremacy more than ever served as a guide and comfort to the colonizers and as a rationale for coercion of their troublesome subjects'.20 Those ideas were reinforced by the theory of the inevitability of human evolution and progress associated with Herbert Spencer, 'survival of the fittest',21 and Social Darwinism, which allowed an 'advanced' nation to see itself as saving a 'backward' nation from savagery, offering a helping hand to 'races struggling to emerge into civilization'22 in return for their country's riches. The English soldier's patronizing contempt for the cultural and religious differences of other countries is caught in Kipling's 'On the Road to Mandalay':

An' I seed her first a-smokin' of a whackin' white cheroot,

An' a-wastin' Christian kisses on an 'eathen idol's foot:

Bloomin' idol made o' mud —

What they called the great Gawd Budd —

Plucky lot she cared for idols when I kissed her where she stood!

[Performance by present author]

This attitude clearly stems from the above-mentioned ideas which, in combination with late nineteenth-century imperial expansion, 'tended to exacerbate more racist notions of black and brown inferiority'.23

Before the development of Darwinian anthropology (The Origin of the Species was published in 1859), and while ethnology was in its infancy, the quality of 'Englishness' was deemed to lie largely in the possession of certain virtues. Indeed, in English Traits, published in 1854, Ralph Waldo Emerson fails to find anything particularly English about the rural population at all; his main concern is with the urban bourgeoisie. In 'The Englishman', a song published about 1840 which was very well known in the mid-century (it reached its twentieth edition by 1870), the Englishman is defined geographically by reference to his island home, his vast domain, and the symbol of his territorial possessions, his flag. In 'The Men of Merry England', Englishmen are defined by their freedom, bravery, and [175/176] enterprising spirit; but these are the same aspects of Englishness with which the eighteenth-century bourgeoisie would have identified, and which had already been celebrated in songs like 'Heart of Oak' (1759). Indeed, in a major new contribution to a neglected area of historiography, Gerald Newman locates the rise of English nationalism in the second half of the eighteenth century.24 He sees it emerging from anti-aristocratic and anti-French feelings: the 'real' Englishman is therefore projected as one who loathes foppishness and who lays claim to virtues the French are presumed to lack, such as sincerity, honesty, and independence. Roast beef becomes a symbol of Englishness because the French eat fancy ragouts; 'The Roast Beef of Old England' (1734) makes reference to 'effeminate France' and the 'vain complaisance' of the French. This song became part of the ritual of grand military banquets throughout the nineteenth century, being used as the announcement of dinner.

Even if an image of English national character was being assembled well before the nationalist enthusiasm of the late nineteenth century, the issue of whether or not there was a distinctly national character to the musical side of English songs, as opposed to their literary content, had been largely ignored. It was not even vital for the music of a 'national song' to be of English origin; Braham's The Death of Nelson' was rumoured to be founded on a French air.25 The use of the description 'national' as a reference to words rather than music allows for a seemingly paradoxical situation in which 'God Bless The Prince of Wales' can be viewed as a 'truly national song' (12), and the Orange Lodge song 'Derry's Walls' which borrows the same Brinley Richards melody can also be called a 'National Song'.27 William Chappell published two volumes entitled National English Airs in 1838 and 1840, but though by 'national air' he was avoiding some of the restrictive connotations pertaining to 'national song', he was apparently dissatisfied with that description, for when he issued a much larger collection to subscribers in 1855-59, which used the previous publications as its basis, he called it Popular Music of the Olden Time. There is no analysis of musical style in Chappell's work, and no sense ofmusico-sociological endeavour, nor is there any acknowledgement of the respective musical contributions of different social groups. He seems to have been primarily motivated by the desire to trace the music mentioned in literary sources, such as Shakespeare plays, and the 'olden time' refers mainly to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Chappell was the founder of the Musical Antiquarian Society and saw his publication as 'not only a repertory of English popular music, but also a continuation of the literary work of Percy and Ritson'.28 After Chappell's death, and during the folksong-collecting craze of the 1890s, his work was republished, but now its title, Old English Popular Music, carried a specific reference to nationality. It was also in the 1890s that Frank Kidson published his English Peasant Songs, which parts company with Chappell in two ways: first, Kidson claimed that he was originally driven to collect songs in order to demonstrate the absurdity of the accusation that the English had no national music, thus implying that Chappell had failed to counter that accusation;29 second, Kidson locates this English national musical style in the music of a distinct social group. Kidson, like other folksong collectors, was interested in finding a rural population who had remained unaffected by the [176/177] commercially oriented music of the cities; his use of the word 'peasant', till then rarely used in the nineteenth century, is an indication of his wishful thinking. Before the interventions of people like Kidson and Sabine Baring-Gould, the musical traditions of the 'lower orders' were 'regarded with scorn'.30 In fact, it was only very late on in the century that folksong gained entry to the drawing room, and then in a mediated form. Rather than learn about Englishness from rustic labourers, who, as has been noted, were for most of the century not necessarily thought of as being typically English anyway, the bourgeoisie were more concerned to win these people over to an appreciation of morally elevating drawing-room ballads and blackface minstrel songs performed in village halls and the like. Ironically, the early folksong field-collectors were partly motivated by contempt for the sentimentality of bourgeois music-making, seeking instead an honest, healthy and spontaneous alternative in the English countryside.

The Folksong Movement had two noticeable effects on the drawing-room ballad at the close of the century and during the early years of the next: an exotic spicing was now almost always added to music intended to evoke other lands (pointing to the contrast with Englishness), and it became fashionable to write ballads containing regional vernacular speech. The new exoticism is evident if music concerning India composed in the middle of the century is compared with that composed at the end of the century. 'Jessie's Dream' (1857), a story of the Relief of Lucknow, makes no attempt whatsoever to introduce any music remotely Indian in character, though it manages to include snatches of 'The Campbells Are Coming', 'Auld Lang Syne', and 'God Save the Queen'. Adolphe Schubert's descriptive fantasia 'The Battle of Sobraon', published in London in 1846, has the Sikhs marching to their entrenchments to the missionary strains of 'There Is a Happy Land'. In John Pridham's plagiarized version, 'The Battle March of Delhi' (1857), this section is labelled 'Indian Air (at a distance)'.

Although reputedly Indian in origin, the tune above suggests nothing of the exotic atmosphere conveyed by the introduction to the 'Kashmir! Song' (words by L. Hope, music by A. Woodforde-Finden) from Four Indian Love Lyrics of 1902. See the following musical example:

Exotic elements can, in fact, be found in songs earlier in the nineteenth century (for example, Norton's 'No More Sea'), but they are a rarity and, even in 1892, Cobb's 'Mandalay' (a setting of Kipling) has nothing exotic about it; indeed, it is a waltz which, in the shape of an arrangement by Bewick Beverley, became one of [177/178] the most fashionable dances of the season.

In contrast, Oley Speaks in his famous 'On the Road to Mandalay' of 1907 uses an insistent rhythm joined to ominous harmonies for the verse sections and exotically colours the references to palm- trees and temple bells. In the 1890s an exotic turn of musical phrase came to be used to indicate non-European countries in general; Florence Turner's highly flavoured music for the 'Egyptian Boat Song' of 1898 owes, in reality, no more to any alternative musical culture than did Frederic Clay's 'I'll Sing Thee Songs of Araby' of 1877. Franklin Clive illustrated the late Victorian all-embracing image of the far-off land in 1899, when he discovered that he could sing Kipling's 'On the Road to Mandalay' not to any pseudo-Burmese music, but to Walter Hedgcock's 'Japanese' music composed in 1893 for 'The Mousmee' (Performance by present author).

It was probably a conjunction of imperialist sentiment, the Folksong Movement, and enthusiasm for Kipling's verse which lay behind the upsurge in the use of vernacular speech in drawing-room ballads. Devon and Drake were favourite subjects, a well-known example being Newbolt's poem 'Drake's Drum', set by Hedgcock in 1897, but most familiar in C. V. Stanford's setting of 1904. Imperialist sentiment is relevant here because imperialist endeavour and 'chivalric aspects of colonial adventure' (Rich 25) could be related to the Elizabethan merchant adventurers like Raleigh and Drake (the message 'Sail overseas and conquer!' might easily have been inferred from Millais' painting The Boyhood of Raleigh). In 'army ballads' the rugged sergeant figure is probably a Kipling bequest; the humorous as well as intimidating aspects of his character are exploited in later ballads like 'A Sergeant of the Line' (1908), 'The Company Sergeant-Major' (1918), and 'When the Sergeant Major's on Parade' (1925).

In spite of all the activity surrounding the search for a specifically English musical style, there was no consensus about what that style consisted of in the late nineteenth century. In the 1890s some writers on music were still pointing to the bourgeois patriotic song as the 'national song', but claiming a national character for the music as well as the words. 'Rule, Britannia' is described in one song collection of this period as 'one of the finest national tunes we have, thoroughly expressive not only of the words, but embodying in its bold, ringing, martial-like strains, the very character and spirit of the British nation'.32 Whether a ‘bold, ringing, martial-like strain’ springs from the ‘character and spirit of the British nation’ or from the use of certain well-trodden Western compositional techniques is a matter which can be disputed. The opening of the first verse of ‘Rule, Britannia’ will serve as an illustration.

The use of a march metre and the construction of a tune around the tonic arpeggio, suggestive of a fanfare, undoubtedly conveys a martial mood (the bugle, for example, can play only notes of the tonic arpeggio, so all bugle calls share this character). If this is typically English, it obviously follows that so, too, is the tune of 'The Englishman',

and also that of 'The Men of Merry England'.

There are, of course, countless other nineteenth-century English 'national songs' of this character; but perhaps this melodic and rhythmic device ought to be considered first and foremost as a feature of songs signifying a militaristic rather than a national character. Compare the refrain of 'The Old Brigade', which begins as follows:

The refrain of 'The Deathless Army' begins in similar fashion.

Again, it need hardly be added that other examples are legion. It may be noted that the 'Marseillaise' is a tune of this type; one then needs to ponder why military bands in England were prohibited from playing it till 187933 and why the writer [179/180] quoted above, who was so enthusiastic on the subject of'Rule, Britannia', found that in the case of the 'Marseillaise', 'there is an element of danger in a song of this kind'.34

If Britishness or Englishness implies unquestioning devotion to the concept of a homogeneous nation, there can be no danger for the bourgeoisie in a song like 'Rule, Britannia'. Nor was any danger perceived in the new pastoral image of Englishness which gained ground rapidly in the early twentieth century and took its idea of the typical expression of English character in music from folksongs like 'Searching for Lambs'.35

Here, the rolling irregularity of the English landscape finds its melodic counterpart, and the modality and lack of clearly implied harmony (there is no obvious choice of chord for bar two, for example) suggest an Eden undented by the commercial music industry. Yet folksongs, as the new 'national songs', soon became part of that industry. Whether 'Searching for Lambs' in any better served by the label 'national' than is 'Rule, Britannia', is once more a matter for ideological debate. [180/181]

Last modified 18 June 2012