The amount of concert promotional activity taking place in Britain multiplied rapidly in the second half of the nineteenth century. It was symptomatic of the increasing commercialization of music during this period. Ballad concerts may have begun in London but were soon found spreading to all major cities, and also to holiday resorts, where the spa orchestras 'were in part heirs of the ballad concerts, the "Grand Morning Concert" or "Soiree Musicale" which for long delighted middle-class Londoners' (Young 127). 'Morning' performances, incidentally, were conventionally given in the afternoon, a practice which continued when the word 'matinee' was substituted for 'morning' in the 1880s. A seaside resort within easy travelling distance from London by rail, like Brighton, found it a simple matter to attract money into the town during the lean winter months by presenting a concert season. This was good news, too, for the railway company who could advertise a range of special offers for the Brighton Season and fill up their Pullman Drawing Room Cars which would otherwise have lain empty in February.

Many commercial and industrial centres started up festivals — often, as in the case of Leeds (1858), Bradford (1853), and Huddersfield (1881), to promote their new town halls. Birmingham boasted a festival which could be traced back to 1768, but most of the festivals which dated from before the nineteenth century were cathedral festivals, such as the Three Choirs Festival and the Norwich Festival. In the industrial North the sponsors of festivals would generally be a combination of business magnates, local traders, and the local authority. Some- times the landed gentry might offer support to a rural festival: the Worsley family, for instance, sponsored a festival in the small Yorkshire village of Hovingham (1887-1906). Sometimes a festival was begun by moral crusaders; the Harlech Festival was organized by a group of temperance choirs in 1867. New festivals usually trumpeted the fact that, like the cathedral festivals, they were taking place for a charitable rather than a business purpose: the Glasgow Festival of 1873, for example, raised £1000 for the Infirmary, and the Birmingham Triennial Festival traditionally handed over its profits to the General Hospital.

Festivals were just one part of the rapid spread of concert activity, however, and the lack of a festival did not necessarily mean a city lacked music; Liverpool, for example, never managed to get a regular festival off the ground, but that may have been because there was already so much happening there, including a [120/121] thriving Philharmonic Society. In Hull, a city which never had a festival, regular concerts were promoted by local traders and others. The music shop Gough and pavy brought up Edward Lloyd in February 1893 to sing his latest ballad-concert success, 'The Holy City', accompanied by its composer at the piano. Although many concert promoters were keen to offer cheap rates (the standard cheap rate being 1s) in order to increase the size of the audience—and this was a concession normal at promenade concerts which had developed from pleasure-garden music-making — there remained a few elitist bodies who were concerned to keep out even the lower middle class, let alone the working class. The Philharmonic Society in London, which long enjoyed a monopoly in orchestral performances, refrained from offering cheap rates during the entire time they played at the aristocratic Hanover Square Rooms; they did, however, change their policy when they transferred to St James's Hall in 1869. In Manchester entrance to the 'Gentlemen's Concerts' was by old-fashioned subscription only, and patrons were required to wear full evening dress. Ironically, the organizers of the massive triennial Handel Festivals held at the Crystal Palace, occasions which seemed designed as an illustration of the classless universality of Handel's genius, never made seats available at a cheap rate: in 1857 admission was 10.s. 6d. and reserved seats cost 1 guinea. Jullien mounted a rival cheap festival that year in the Surrey Gardens Hall.

The majority of promotional bodies were on a constant look-out for new ways to entice more people into concerts. Promoters in the London suburbs had to put on programmes of great diversity to fill halls. The Beaumont Institution in the East End endured much ridicule in 1860 for a programme mixing items from opera and oratorio with drawing-room ballads, organ music, and other musical fare. The directorate responded to criticism by saying, 'the hall was packed, the audience encored half the pieces, and - we paid our expenses' (Pearce 219). Smoking concerts were started in London in the 1880s; those who wished to luxuriate in tobacco smoke while listening to 'good' music now had only to look for an advertisement such as 'Grand Cigarette Concert' (Scholes 1:197). Founded in the same decade was the Coffee Music Halls Company, Limited; the first venue they acquired for a coffee music hall was the then run-down theatre known as the 'Old Vic'.

There were also new developments in theatrical performance. A large portion of the bourgeoisie had always eyed the theatre with suspicion as a place of dubious propriety (see Chapter 1); it was to overcome just this fear of offended respectability that Thomas and Priscilla German Reed opened their 'Gallery of Illustration' in Regent Street in 1856. They aimed to provide impeccably wholesome entertainment and pointedly refrained from calling their premises a theatre, although it was, in fact, licensed as such by the Lord Chamberlain.4 Advertisements announced their dramatic performances as 'Mr and Mrs German Reed's Entertainment', a phrase suggestive of 'at home' functions among polite society. In the early days the entertainment simply consisted of the husband-and-wife team singing and acting, Thomas adding musical accompaniment when needed on piano or harmonium. After 1868 the company increased and included, among others, their son Alfred and the barrister turned musical mimic, Corney Grain. They were now able to mount a variety of [121/122] small-scale burlesques and operettas. Both Gilbert and Sullivan had independently supplied material for the Gallery of Illustration before their first formal introduction to each other there in 1871 (DNB VII: 108). The German Reeds' provision of wholesome comedy for the middle class proved to be a great influence on the later development of the Gilbert and Sullivan partnership and, indeed, on the acceptance of comic song in the drawing room, till then almost solely represented by 'Simon the Cellarer'. In the last decade of the century another new form of salubrious entertainment, the pierrot show, was developed at seaside resorts to serve the leisure-time interests of the lower middle class who were by then confirmed in the custom of taking an annual seaside family holiday. Dressed as clowns the actors may have been, but tearful ballads were sung in plenty.

Prominent among concert promoters were the music publishers themselves. Tom Chappell of Chappell & Co. financed the building of St James's Hall in 1858 and the presentation of the Monday and Saturday 'Pops'; he may have found inspiration for these 'popular concerts' in the well-attended Wednesday Concerts at the Exeter Hall (started in 1848). Naturally the opportunity was not missed to display the firm's instruments and sheet music at St James's Hall. Speculation also played a part in Chappell & Co.'s success; Tom Chappell bought the publishing rights of Balfe's The Bohemian Girl and Gounod's Faust before either of them had been staged in London (though Faust had actually been given a concert performance at the Canterbury music-hall). The risks involved in this sort of speculation could be high: Tom Chappell had paid around £100 for Faust which was expected to fail, but John Boosey paid £1000 for Gounod's next opera, Mireille, which was expected to be a triumph, yet turned out to be a flop (Boosey 23-24). Publishers looked upon operas as storehouses of profitable individual sheet-music items. In a notorious case a publisher forced Jullien to take offan acclaimed production of Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor at Drury Lane in December 1847 and replace it with Balfe's new opera, The Maid of Honour. Jullien had signed a contract committing him to a penalty of £200 if he failed to put on Balfe's work as soon as it was ready, and the publisher was keen to bring out the 'favourite airs' in time for Christmas. Chappell & Co.'s sphere of influence extended beyond their own publications and promotions: Tom Chappell was one of the original directors of the Royal College of Music and one of the original governors of the Royal Albert Hall. Chappell & Co. also helped to finance the first D'Oyly Carte Company, though they soon acquired a deeper vested interest in its success by publishing almost all the Gilbert and Sullivan operettas.

The new series of Saturday afternoon 'Pops' begun by Chappell in 1865 may have influenced John Boosey's decision to establish the London Ballad Concerts at St James's Hall in 1867. The market for the 'popular concert' could be seen to be growing, and the profitable ballad catalogue Boosey had built up no doubt suggested an area for further expansion. The main factors in Boosey's success seem to have been the mixture of well-known songs among the new, the engagement of celebrated singers, and the lack of 'heavy' items in his programmes. A reviewer in 1871 picks up on these points:

Mr Boosey has been giving on successive Wednesdays a new series of these highly popular entertainments, and by a judicious admixture in the programmes of things [122/123] new and old, as well as by securing the services of many of our principal public performers, has made them thoroughly attractive. There are thousands who would never go to St James's Hall to hear a quartett [sic] or a sonata, that can thoroughly appreciate a 'good old song', and for this numerous class the Ballad Concerts supply exactly what they like. [The Monthly Musical Record (1 February 1871): 24.]

In their turn, the Boosey Ballad Concerts were later emulated by Chappell; in fact, William Boosey, the adopted son of John Boosey and well-versed in ballad affairs, was engaged to run their first series in 1894. William Boosey, who went on to join Chappell & Co., almost single-handedly built up their ballad catalogue. The suggestion that he do so came from himself:

Mr Chappell's first idea was to engage me to run a series of ballad concerts. ! explained to him, however, that he was securing the least valuable half of the loaf, and that the concerts would be of no use to him unless he could count on me to provide him at the same time with a new ballad catalogue. [Boosey 89]

Besides Chappell and Boosey, the other member of the big three British music publishers of the nineteenth century, Novello, also promoted concerts. Having an enormous choral catalogue, it is no surprise to discover that they were especially keen to promote oratorio concerts. That Bach's St Matthew Passion was being so widely taken up in the 1870s demonstrably owed more to Novello's new cheap octavo edition, coupled to their promotional efforts, than to the earlier and more musicologically celebrated Mendelssohn revival of the work. Novello also showed business acumen in taking over the firm of Ewer & Co. who possessed the publishing rights to Mendelssohn's Elijah, a work which held second place only to Handel's Messiah in relation to its frequency of performance.

Before the opening up of the country by rail, the market for sheet music was fraught with transport difficulties. These problems account for music publishing outside London having reached its peak in the early industrial period of 1790-1830. Even then, the publisher outside London was often a branch of the publisher in London: William Power of Dublin, for example, who published Moore's Irish Melodies, was related to James Power of London. George Thomson of Edinburgh (mentioned in Chapter 1 in connection with Beethoven's arrangements of Scottish airs) was independent, but his business ended in bankruptcy. Bremmer and Cori in Edinburgh were branches of their respective London firms. After 1830 Edinburgh and Dublin were the only serious rivals to London as places for music publishing. It should be pointed out, however, that a fair amount of publishing activity did take place in Bath, Cambridge, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Oxford, York, and Aberdeen. Many music publishers relied on sales of instruments as well as sheet music; salient names here are Chappell, Metzler, D'Almaine, and Boosey (the latter began manufacturing wind instruments in the 1850s and moved into brass also when they bought up the business of Henry Distin and Co. in 1868). Those companies concentrating on sheet music sales alone had to pin-point their market with care. In the publication of drawing-room ballads, George Davidson (who set up business around 1833 and became 'The Music Publishing Co.' in 1860) targeted the cheap end of the market, cutting costs by using musical type; by 1870 he was able to offer songs in his Musical Treasury at a fraction of the price of his rivals (though, naturally, both print and [123/124] paper were of poor quality): 'Popular Songs, in threepenny sheets, many with elegant illustrations and portraits in colours . . . The original and only genuine music for the million.'9 In the middle of the market was the Musical Bouquet which flourished under the proprietorship of Charles Sheard who took it over in 1855. At the top of the market was Robert Cocks who had the prestige of royal patronage and of owning the lease of the Hanover Square Rooms. The carving up of the market in various layers of price relates to the increasing commercialization of music and the interaction of supply and demand. Back in 1811, for example Chappell had begged leave 'to aquaint the nobility and gentry' (Mair 10) that he had set up in business, a statement indicative of the restricted market at that time. By 1870 no publisher catered exclusively for the aristocracy and wealthy bourgeoisie, and all the larger publishers were selling internationally. For international sales a publisher had no need of a branch in every country: in the colonies, for instance, companies could be found specializing in importing music, like Harold & Co. Ltd, the 'Musical Depot' of Calcutta. Boosey & Co. did open a New York branch in the 1890s, but Chappell waited until 1906 before following suit.

Perhaps because of growing demand (the entertainment industry was booming in a time of recession, as it has done since), perhaps because of increasing standardization of publishing format (particularly applicable to music-hall songs), or perhaps because of innovative technology (the rotary press was but one method of faster production), the price of sheet music was being pushed down in the later nineteenth century. Nor must one ignore the general economic background of continually falling prices from 1873 to 1896, and factors such as the money supply (gold reserves) which also may have had a bearing on commodity prices, such as paper.11 Drawing-room ballads were falling in price from an average 4s. in the 1860s to 3s. in the 1870s and to 2s. in the 1880s, and this was only the marked price; most publishers had an arrangement to sell at half the nominal price. There were cheap postal arrangements, too, some sheet music stockists even offering to supply music post free. In the 1880s Moutrie and Son of Baker Street were charging a maximum of 1s. 6d. per item, post free, and a further reduction was made for soiled copies.12 Not to be overlooked amongst all the bargains were the albums of 'standard works' and the 'cheap editions' that were being produced in great quantity.

In respect of the biggest ballad successes the market for transcriptions and arrangements was vast: in the case of 'The Holy City'(1892), for example, Boosey published a whole range of spin-offs from the original, including a German translation, 'Die Heilige Stadt' (1896), a version with chorus parts (1894), a military-band arrangement (1892), and an organ transcription (1894). Note that the military-band version appeared in the same year as the ballad's first publication; Boosey's connection with wind instruments made them eager to publish 26-part band versions of their ballad triumphs (the vocal melody often being carried by a solo cornet or euphonium). Having been the first to see the potential of the drawing-room-ballad market, Boosey & Co. were also in a position to avail themselves of their extensive back catalogue and reissue former favourites for a new generation of consumers. 'Come Back to Erin', reissued in [123/124] 1893, proved more profitable over the next two decades than it had been in the late 1860s and 70s.

The curse of the publisher was the pirated edition. An area particularly vulnerable to piracy was blackface minstrel song. Where the composer was assumed to be an anonymous black American, any number of authorized editions might appear, but even as eminent a composer as Henry Clay Work was not safe from such treatment. In the 1870s the reputable publishers H. D'Alcorn & Co. produced a 'Grandfather's Clock' which purported to be the 'authorized version' of 'The Great Song, sung with unbounded applause in Uncle Tom's Cabin.' Only the work of an arranger, J. E. Mallandaine, was credited. Hopwood & Crew advertised an 'authorized edition' of Christy's Minstrels songs and ballads, but it did not prevent the more up-market Musical Bouquet from publishing many of the same songs in versions by their own house arrangers. Publishers were treading on each other's toes because the market for minstrel songs was so extensive, reaching into drawing room, music-hall, and even the classroom. H. D'Alcorn included minstrel songs in their albums of Easy Piano Music for Children (while they felt unable to include items from their huge music-hall catalogue), and Hopwood & Crew pointed out that their minstrel songs were 'ever welcomed and highly appreciated in the drawing room, and the greatest favourites with teachers in Class Instruction'.13

Stationers' Hall designed by by Robert William Mylne (1817-1890. Click on images

to enlarge them. [Not in print edition.]

Copyright was often either not strictly enforced or offenders were treated leniently in the nineteenth century. Moreover, there was a degree of confusion about some of the terms of the Copyright Act of 1842. Under that Act copies had to be registered at Stationers' Hall to protect copyright; it would then last for a period of forty-two years or the author's lifetime plus seven years, whichever was longer. A question arose, however, concerning the copyright of titles. The last page of 'It's Just As Well To Take Things in a Quiet Sort of Way' bears a warning from the publisher H. D'Alcorn against any attempt to pirate 'the Words or Title of this Song'. Yet one judge expressed grave doubt 'as to whether copyright could be claimed at all to a mere title'.14 Another problem was in deciding how much imitation could be allowed before a composer was liable to the charge of plagiarism — Sullivan's 'When a Merry Maiden Marries', for instance, begins in almost identical manner to the refrain of Molloy's 'Love's Old Sweet Song' ('Just a song at twilight' — performance by author). A further problem arose concerning the distinction between copyright and performing right (known then as 'acting right'). Note the following caution which appeared on Hopwood & Crew's publication of Harry Clifton's 'Pretty Polly Perkins of Paddington Green' (performance by author): 'This song is legally protected, and cannot be sung in Public without the written permission of the Author.' In this case, presumably, Clifton had sold only the copyright to the publisher and not the performing right. Many singers assumed that they purchased their songs from publishers who owned both copyright and performing right; it was certainly in the publisher's interest to own both, since a song that could not be performed in public without special permission would not sell as well as one which could. Under the strict terms of the Act, however, the performing right needed to be entered separately at Stationers' Hall. There was a notorious Mr Wall who managed to purchase performing rights from impecunious composers or their [125/126] descendants, register them, and then have singers and bands prosecuted for performing them. The following throws light on his method:

There is a certain old song, for instance, 'She wore a wreath of roses', which had been sung for a great number of years publicly in all kinds of concert-rooms, and no one ever dreamt of stopping the singing of it; it was sung by Phillips, Rudersdorff, and many singers of the time gone by, and then all of a sudden, not the publisher, but Mr Wall, secures the reversion of the words, I suppose, and registers that reversion, and immediately comes down on singers singing his song who have been singing it all their lifetime, and compels them to pay forty shillings.15

The activities of Wall led to publishers like Boosey attaching the comment 'May be sung in public without fee or license [sic]' to their ballads (although Boosey was adamant in prohibiting parodies). Today, it is necessary to apply for permission to perform copyrighted songs in public to the Performing Right Society Ltd, the independent body now serving the interests of composers and their descendants. Ironically it means that some Boosey ballads, previously published with a disclaimer, cannot now be performed in public without a fee since under the terms of the 1911 Copyright Act copyright protection was extended to the author's lifetime plus fifty years, and in the 1990s European copyright was extended to 70 years after the death of the author.

Until the reforms of 1902, 1906, and 1911, copyright legislation was largely ineffective in the face of the massive piracy of the late nineteenth century. In consequence, it was not only publishers who suffered; composers paid on the royalty system were inevitably deprived of part of their rightful income. John Boosey had been the first to allow composers a royalty on all copies of their music sold (Mair 33). The very first composer to benefit from the royalty system is said to be their number one ballad composer of the late 1860s, Claribel (Simpson 145). Before the existence of the royalty system, copyrights were sold outright, and sometimes brought little to the composer, as Henry Russell explains:

I have composed and published in my life over eight hundred song's, but it was by singing these songs and not by the sale of the copyrights that I made money. There was no such thing as a royalty in those days, and when a song wa old it was sold outright. My songs brought me an average price often shillings each, that is to say, my eight hundred songs have represented about four hundred pounds to me, though they have made the fortune of several publishers.18

Russell's celebrated precursor, Charles Dibdin, did somewhat better for himself when he sold his entire stock of 360 songs to Bland & Weller of Oxford Street for £1800 with £100 per annum for three years after, for such composition as he might produce during that period.19 In the 1860s the outright fee for a song could vary from £1 to £10. When royalty payments gained ground - most publishers being forced to follow Boosey's example in order to compete for the best-selling composers - there was also a variety of payments negotiated. The norm was around 10 per cent, but some terms could be very generous: a contract from Hopwood & Crew, who were moving up-market in the 1870s with their take-over of the firm of Charles Coote, offered John Hatton a royalty of 7d. on each copy sold of his ballad 'Faithful Ever' (1875), the value of one copy of which was registered at 1s. 0d.20 Royalties were also negotiated for arrangements: a letter from Sullivan [126/127] to Arthur Boosey, dated 21 April 1877, expresses the former's willingness to accept 3d. a copy for the piano arrangement of'The Lost Chord' (letter reproduced in Young 108). The same letter brings up a problem related to the aggressive ballad marketing of the 1870s and beyond; Sullivan discovered that old songs of his were being dished up with new words by his previous publisher, Metzler, and then advertised as new songs in order to cash in on his Boosey ballad-concert successes.

Professional singers were crucial to sales promotion in two ways: first, they were necessary in making the ballad known, and second, their association with the ballad could be used as a recommendation. Thus, it was important for publishers to include in advertisements of their ballad successes details of who they were sung by. Each ballad would normally have a back page devoted to the publisher's catalogue, with singers' names listed against each item. On the front the singer(s) associated with the ballad in question would be identified after some such phrase as 'Sung with Brilliant Success by', or, if the publisher favoured a softer sell (like Boosey), a modest 'Sung by'. A sales promotion technique well underway in the 1860s, and probably in existence before, was the payment to singers of a fixed royalty for a term of years on each copy of a ballad sold, on condition that they plugged it at all their concert engagements. Publishers had, of course, interested themselves in the repertoire of singers well before the rise of the 'royalty ballad' — it was John Boosey who had sent Tennyson's 'Come into the Garden, Maud' to Balfe, asking him to set it for Sims Reeves (Boosey 17) — but the crude inducement of hard cash raised fiercely debated matters of taste. The acceptance of a royalty threw doubts on the artistic integrity of the singer:

whether honest art is not more important than the twopence or threepence a copy is a serious question. I strongly urge that musicians should elevate the taste of the public, and should guide it. They can do it, and they have a moral duty to do so, especially those who are not obliged to work for the penny that brings the bread, and who can afford to refuse the bait.23

Some singers hit back with their own moral arguments, portraying themselves as public servants and placing the onus for questions of taste on the audience: 'the public which remunerates the singer . . . has a right to demand whatever will amuse it ... I cannot enter into the question of public taste here; being public property I have no right' (Santley 56). The attitude above, however, can easily slide into contempt, best exemplified by the notorious, though probably apocryphal, advice Nellie Melba is supposed to have given Clara Butt on the eve of the latter's Australian tour: 'Sing 'em muck; it's all they can understand' (Scholes I, 296). The castigation of singers who accepted payment for promoting songs has persisted in modern surveys of the period (though under different guises, like accreditation with part of the composition, the practice has continued to embrace singers as different as Al Jolson and Elvis Presley): 'It was not to the credit of celebrity singers of the time that they rushed on to the band wagon, sponsoring drivel because the chore was well-paid, bribed to insert new drawing-room ballads in their programmes' (Pearsall 95).

The question arises, however, as to whether or not singers saw themselves as 'sponsoring drivel'. The tenor Edward Lloyd expressed surprise that he should not sing 'popular songs', provided one or two conditions were satisfactorily met: [127/128] 'Why not popular songs? The people like them, and if the words have a good tone and the music is pleasing to the audience, why should I not sing them.' In her later life, Clara Butt, the last celebrity singer engaged to promote 'royalty ballads', found it impossible to recollect any drivel she had sponsored: 'I have sung many hundreds of songs during my career, and I do not think I have sung any bad ones' (Scholes I, 293).

The 'royalty ballad' system did not always operate as smoothly as publishers wished, either. At first they assumed that only the leading singers needed to be paid royalties, and that lesser-known singers would automatically take up the same songs. Nevertheless, it was not long before a small publisher, Hutchinson, started paying those lesser singers to promote his own firm's songs, a move which forced the big publishers into this area as well. Another problem was created by the very public whose taste so many were avowedly eager to please. When William Boosey started the Chappell Ballad Concerts, his business instinct told him to engage the well-known names from the Boosey Ballad Concerts, yet it is apparent, reading between the lines of the following comment, that problems ensued regarding the introduction of sufficient new material: 'I used to find ballad concerts handicapped by it being necessary so very frequently to repeat the same songs and solos over and over again' (Scholes I, 294). The audience were naturally insistent that these singers perform their 'greatest hits', most of which were in the Boosey and not the Chappell catalogue. Furthermore, singers tended to have only a handful of encore pieces, often dating back to the days when they first built their reputation, which served them for an entire career: for example, the tenor Sims Reeves sang 'The Death of Nelson', 'The Pilgrim of Love', 'The Bloom Is on the Rye', and 'The Bay of Biscay' as his standard encores for thirty years; none of these were 'royalty ballads'.

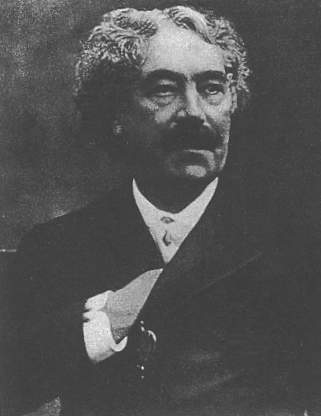

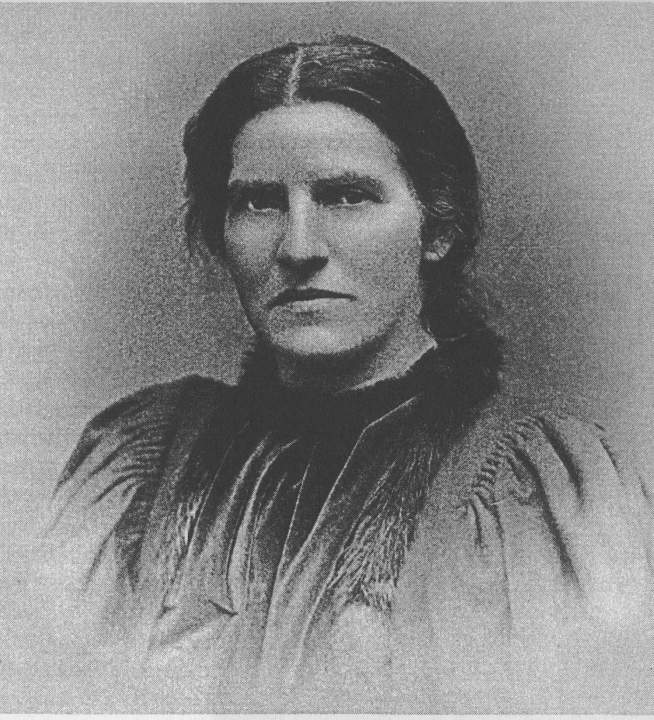

Sims Reeves (1818-1900) has been disdainfully marked down as 'an all-round singer who went wherever the pickings were greatest' (Pearsall 222); but is this fair? Unlike the famous visiting Italian tenors, Reeves could not make his money on a few months of opera in London and spend the rest of his time performing at aristocratic functions. He did show great enthusiasm and skill as an opera singer, but no English tenor could compete with the status accorded to Italian tenors, like Mario, and he was seldom given opportunity to display his talents in that field. Where Reeves sang, then, cannot be exclusively attributed to personal greed; moreover, at times he took a principled stand which cost him dearly. A controversy raged in the late 1860s and throughout the 1870s concerning the height of English as opposed to Continental pitch. In 1868 Reeves made a resolution not to sing except at Continental pitch. It was a decision which caused consternation: 'Those who regarded musical art as a matter of pounds, shillings, and pence could not understand how a singer could forgo such a comfortable source of income' (Pearce 256). All the same, he stuck by his refusal for over three years, fruitlessly as it turned out, since orchestras were not willing to spend money on the purchase of lower-pitched Continental wind instruments. Another point of honour for Reeves was his determination never to sing if he felt unable to do justice to his art; since he was plagued with a delicate throat, this meant the surrender of fees which 'amounted during his career to no less than £90,000' (Pearce 306-7). [128/129] In the late 1870s Reeves shared with the young American contralto Antoinette Sterling (1850-1904) 'the chief place amongst our ballad singers' (Laurence I, 176). Sterling, far from jumping at the chance to promote new 'royalty ballads', was renowned for the careful perusal she gave, particularly to texts, before agreeing to perform them. Even the penetrating critic Shaw was drawn to the artistic honesty other singing:

Ballad singing is usually accompanied by coquettish smirks, a smile at the end of each stave, and an absurd prolongation of the pathetic phrases . . . These petty practices Madame Sterling has never condescended to employ ... but relies simply on the rapid sympathy inspired by her voice's strange tone quality. [Laurence I, 176-77]

Sterling's technique was not without its faults, however; Shaw criticizes her for occasional incorrect phrasing and a lack of fluent execution. Her early vocal studies had been in New York, and the further tuition she received on the continent was unusual in not including study in Italy. When she settled in England in her mid-twenties, she developed an individual and virtually self- taught style. Here she was breaking newground and forming a closer relationship [129/130] to the drawing-room amateur than to the sophisticated concert artist. Study in Italian vocal techniques was an almost mandatory requirement for concert singers. Her most prestigious contralto predecessor in ballad singing, Charlotte Sainton-Dolby (1821-85), who had retired from professional performance in 1870, had been coached by Crivelli at the Royal Academy of Music. Reeves himself had studied in Milan, and his great predecessor, Braham, had studied with Rauzzini in Bath. An Italianate technique was expected and continued to carry the highest status, even when many ballads were moving, under the influence ofMolloy and Adams (not to mention blackface minstrelsy), away from an Italian style. The status of things Italian had its origin in aristocratic taste (see Chapter 1), and it is to be noted that Queen Victoria was taking lessons in singing from Tosti in the 1880s. Some singers were still adopting Italian names at this time: for example, the bass Signer Foli (Alien Foley, 1835-99).

Early in the century the pre-eminent voice range was that of the soprano. Even in mid-century, at the Norwich Festival, Reeves was unable to negotiate a higher fee than 100 guineas, while the committee were willing to pay 300 guineas for soprano soloists. The rise of the tenor soloist was related to middle-class distaste for the castrato voice, which was suggestive of the aristocratic effeminacy they so [130/131] despised (it was not a quality which could be squared with bourgeois ideology). Braham did more than most at the beginning of the century to create the image of the tenor 'superstar'. He was almost certainly the only tenor at that time to command fees like the 2000 guineas Dublin Royal Theatre were prepared to pay for a fifteen-night engagement in 1809.35 In The Enterprising Impresario (1867), Walter Maynard (Thomas Beale) recommends organizers of touring concert parties to calculate on the following basis:

| Soprano | £200 |

| Contralto | £25 |

| Tenor | £200 |

| Bass | £15 |

| Pianist | £50 |

| Violinist | £30 |

| Conductor | £25 |

| [total cost of performers] | £545 |

| Hotel, travelling and servants, say | £150 [Scholes I, 281] |

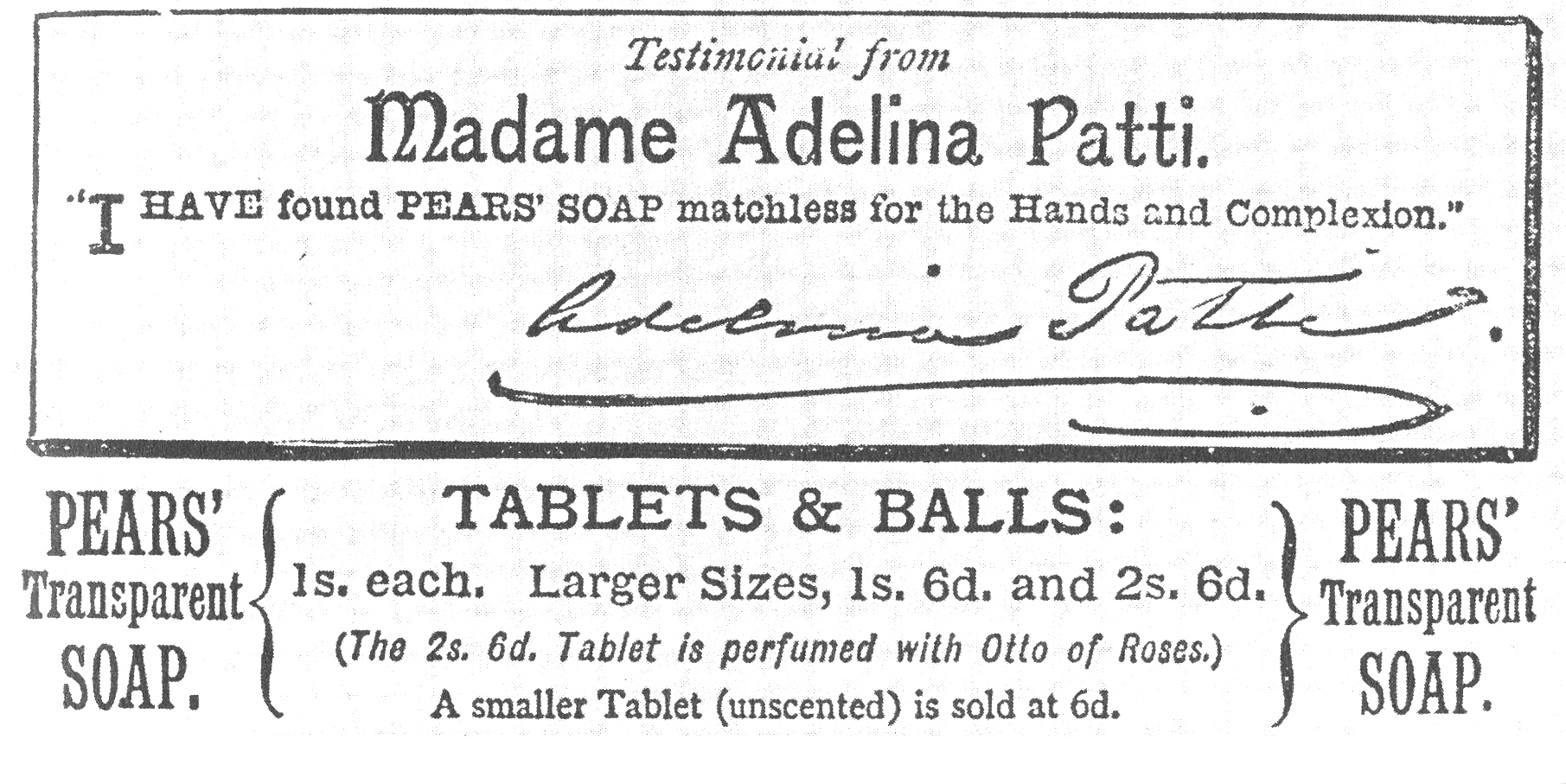

By the mid-1860s sopranos and tenors were deemed to carry equal status as major attractions; the alto and bass merely make up the full quota of voice ranges normal in a concert party so as to cater for four-part harmony. In later years, though sopranos and tenors continued to command high fees, especially if celebrity had been achieved — Adelina Patti's standard fee was £1000 — altos and basses began to better their status as some of their number won fame in ballad concerts. Perhaps they found ready employment in these concerts because they had more time available for such work, or because they were at first cheaper to engage on the 'royalty ballad' system. Whatever the reason, in the 1880s Antoinette Sterling and the baritone Charles Santley (1834-1922) were as acclaimed as any soprano or tenor ballad singer. In a concert given in Hull's Public Rooms on Monday 19 October 1885 it was Sterling and the baritone Michael Maybrick who constituted the main draw, not the soprano or tenor. Another explanation for the enthusiasm for altos and basses may be that the lower voice range is more easily emulated by amateurs; a failed attempt at a low note usually results in a hoarse growl, a far less embarrassing sound than the agonized yelp that attends a cracked high note. One fact is indisputable: the best-known songs of the first half of the century were almost always originally written for soprano or tenor, whereas after 1870 the best-known ballads were almost always for alto or baritone.

Maynard's book had been written before any concert agencies existed in Britain. This state of affairs, however, lasted for barely a year after its publication. Hudall & Co. claimed they were founded in 1868, with the intention of bringing continental fashion to Britain:

Although nearly all Engagements in Italy, France, Germany and Spain, have long been arranged by Agencies, any extensive development of the 'Agency' system as applied to first-class musical performances, was unknown in England till introduced by Messrs. Rudall & Co. [See The Graphic (30 July 1887): 123] [131/132] Concert agencies proliferated in the 1870s and formed a bridge between concert promoters and performers, taking up the negotiation of fees and organizing the details of tours.

Agencies thrived by easing some of the problems created by the complex and rapid commercialization of music in the 1870s. As concert affairs grew ever more intricate, specialists moved into more and more areas. This often meant new ways of making money: for example, programme notes (a rarity before this decade) were soon a regular feature and, although trivial in content, they were expensive in terms of cost, 6d. - ls. being the norm. The commercialization of music was conspicuously evident in the spread of the musical press, which had expanded enormously from the 1840s. Periodical issues of music were the forerunners of the musical periodical, the magazine or journal consisting of articles, criticism, and musical news. Periodical issues of music had begun to make room available for theoretical articles and reviews; an early example of this was The Harmonicon (1823-33). The first periodical, in the sense of a musical journal, was The Musical World (1836-91). In the 1840s periodicals were springing up around the sight-singing movement; Novello, however, made a particularly influential move by taking over Mainzer's periodical and turning it into The Musical Times in 1844. The age of the music publisher's periodical was now under way. It was, of course, useful to have a magazine which could promote the firm's products, but it was not necessary to turn it over entirely to this end; the status of issuing a well-read and respected periodical was itself a form of self-promotion. Robert Cocks started a Musical Almanack in 1849, Boosey took over The Musical World in 1854 and started a Musical and Dramatic Review in 1864, and Augener started The Monthly Musical Record in 1871. Periodicals were important both in terms of their influence and in the stimulus they gave to the supply-and-demand nexus of consumer capitalism. Wherever there was a sufficient expression of minority interest to intimate the possibility of profitable publication, a new specialist periodical was born. From the late 1870s onwards there were even periodicals aimed at those engaged in the music trades themselves. Between 1870 and 1900, all told, over a hundred different musical periodicals were started up at one time or another.

All this, furthermore, occurred simultaneously with the production of new publications performing the traditional service of a periodical issue of music, like Chappell's Musical Magazine and Boosey's Musical Cabinet (both started in 1861), and (also in the 1860s but more down-market) Hopwood & Crew's Bond Street, a monthly magazine of 'popular songs' and dance music. Not to be neglected in this connection was the use made by publishers of the attraction of a musical series to boost sales; there was an obvious appeal to the collector, for example, in Boosey's Royal Edition of operas. Finally, mention must be made of the nineteenth-century equivalent of the compilation album, the speciality now of record companies like K-tel; an example was The Musical Circle, begun by H. Vickers of London in 1881 as a 'fortnightly journal of copyright and standard music, both vocal and instrumental'.

Other branches of the music trades, such as instrumental manufacture and printing technology, have been dealt with in Chapter 2; but the present chapter cannot close without a few words on the subject of industries clinging to the [132/133] periphery of musical commerce. The tobacco industry, for instance, was keen to push the idea that cigarette smoking was good for the voice and throat. Some celebrity singers did smoke — the tenor Edward Lloyd was one38 — but truth was not to stand in the way of good advertising, and even the non-smoker Clara Butt was enlisted to endorse their products. The glamour of singers could be guaran- teed to boost sales of appropriate products: Adelina Patti was expounding the virtues of Pears' soap in the 1880s (See The Graphic [30 July 1887]: 123).

Fry's employed musical metaphors in advertisements for their cocoa ('Strikes the keynote of health' and 'Keeps you up to pitch'). Perhaps cigarette manufacturers did not actually think of themselves as providing medicine — though Wilcox and Co. sold their cigarettes, for the relief of bronchitis, in chemists — but 'musical medicine' was another area for imaginative marketing. Endless products were claimed to improve vocal production and to be conducive to the well-being of the singer. Voice lozenges were being pushed continually in the 1880s; manufacturers quoted eloquent testimonials from singers and reported the award of gold medals for their wondrous lozenges. Despite the sales drive, however, none of them caught on. Most bizarre of all was the attempt to market Italian air. A certain Dr Moffat had voiced the opinion in 1884 that 'the presence of peroxide of hydrogen in the air and dew of Italy had some connection with the beauty of Italian vocal tone' (Scholes 287.) Marchesi, in Singer's Pilgrimage (1923), describes 'amoniaphone' (allegedly compressed Italian air) which was sold in 5s. tubes. One is reminded of Frank Owen's remark in The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists that capitalists would bottle the very air and sell it if it were possible to do so. [133/134]

Last modified 16 June 2012