Credits

Chapter Four, part 4, of the author's Pegasus in Harness: Victorian Publishing and W. M. Thackeray, which University Press of Virginia published in 1992. It has been included in the Victorian Web

with the kind permission of the author, who of course retains copyright.

The first edition of this web version, which was a project supported by the University Scholars Programme of the National University

of Singapore, saw completion in 2001. Scanning, basic HTML conversion, and proofreading were carried out by Gerhard Rolletschek, a Postgraduate Visiting Scholar from the University of Munich, working under the direction of George P. Landow, who

added links to materials in VW. In July 2012 Landow reformatted this chapter.

[Decorated initial by W. M. Thackeray]

Directions

1. This web version has been formatted for Chrome, Firefox, and Safari.

2. Numbers in brackets indicate page breaks in the print edition and thus allow users of VW to cite or locate the original page numbers.

3. Where possible, bibliographical information appears in the form of in-text citations, which refer to the bibliography at the end of this column.

4. Clicking on superscript numbers, which do not form a sequence, brings you to notes, which will appear in the left column; hitting the back button on your browser returns you to your place in the body of the main text.

5. Clicking on links in the text brings you to material in the Victorian Web.

Contents

Frontmatter

Acknowledgments

A Note on Sources

[Pegasus in Harness]

Chapter One: The Man of Business

(In which an assessment of Thackeray's views on Writing and Business is attempted)

Chapter Two: The Literary Tradesman

(In which is traced Thackeray's descent from literary dilettante to literary hack and his ascent to literary tradesman)

Breaking into Print

Odious Magazinery

Book Work

Capitalizing on Apparent Success

A Man of Experience

The Climb to the Top

Moonlighting

Chapter Three: The Writer as a Literary Property

(In which the tradesman extends his market and his wares)

Chapman and Hall

Bradbury and Evans

An Interlude with Smith, Elder and Company

Return to Bouverie Street

The Final Move to Cornhill

Chapter Four: Working the Copyrights

(In which old wine is put into new wineskins)

Copyrights and Contracts

Reaping a Second Harvest: The English Reprints

From Pirates to Partners: American Publishers

The European Reprints and Translations

The Works under George Smith

Chapter Five: Book Production

(In which the curtain rises upon the accountants and back shop)

The Production House

Vanity Fair: Production and Accounting

The History of Samuel Titmarsh and the Great Hoggarty Diamond

Pendennis

Esmond in Three Volumes

Esmond in One Volume

Chapter Six: The Artist and the Marketplace

(In which is debated whether the artist rules the market or the market rules the artist)

The Shaping Influence of the Marketplace

The Force of Chosen Contexts

Chapter Seven: An Epilogue on Prefaces

(In which the speaker of, and the audiences for, the preface and the work are distinguished)

Notes

29.

The details were given by Ray in Adversity, pp. 261, 478. It is probably not true that the book was turned down by Blackwood's Magazine as Sir Theodore Martin inferred in his Memoir of William Edmondstoune Aytoun, p. 132. Robert Colby speculated that Thackeray may have intended it as a companion to Comic Tales (1841); Colby, p. 197; n.10.

30.

The month of publication is conjectured in Catalogue of an Exhibition of the Works of William Makepeace Thackeray, item 36. The earliest recorded review is in the Literary World 3 (9 Dec 1848), p. 896; see Flamm, p. 59. Among surviving Harper and Brothers records (owned by Harper and Row, Inc., but now housed at Columbia University Library) is a manuscript titled "'Harper's Catalogue' 1817-1879" which lists The Great Hoggarty Diamond with the date 8 Dec. 1848.

31.

At least this was Thackeray's intention when he wrote to Williams and Norgate on 24 Oct 1848 that "Messrs. Bradbury and Evans will send you proofs of my little story 'The Great Hoggarty Diamond' wh. I shall be glad to se published by Mr. Tauchnitz, and shall trust him for the terms" (Letters 2: 444). However, Thackeray's letter of 11 Aug 1849 to Tauchnitz suggests that the Miscellanies which was to contain the story was not yet published (Verlag Bernhard Tauchnitz, p. 122).

33.

Line-for-line resetting of new editions is not unusual. The main reason for it in this case was probably to ensure that the reset gathering M would mesh with the preserved setting of gathering N. But other advantages have a hearing: resetting line for line means that end-of-line word divisions and line justification problems are already worked out. Most deviations from exact line-for-line resetting were attempts to improve the look of especially crowded or tight lines.

From time to time, the compositor(s) working on the second edition failed to make the new lines match the line breaks in the first edition. On at least one occasion a textual variant ranged the line-break difference (see. Appendix D, table 1, item 55.9), but for the most part carelessness was the apparent cause, or else the knowledge that if one line did not match, the text could easily be brought back to the proper line ending within a line or two. Differences could result from attempts to loosen a right line; almost as often, however, new tight lines were created in bringing the lines back to the proper endings.

Other examples of line-for-line resetting occur in Thomas Babington Macaulay, Critical and Historical Essays, entirely reset line for line for the second edition and again for the third edition, and in Thackeray's The English Humourists of the Eighteenth Century, which was printed at least three times in 1853 with substantial revisions and considerable line-for-line resetting.

34.

One copy in original paper-covered boards is in the Fales Collection, NYU. Two copies, both rebound, are at the Library Company of Philadelphia. A fourth copy, also rebound, is in the British Library (C.71.b.12). A fifth copy, rebound and extra-illustrated but with the original covers bound in, is at the Huntington Library. A special note of thanks is due to Mrs. Lillian Tonkin of the Library Company for her cooperation.

35.

For a description of the work-and-turn method and diagrams suggestive of the impositions mentioned, see Gaskell, p. 83, figs. 52 and 60.

36.

Nor is there any reason to think that standing type and a stereotyped copy were imposed together to produce a single sheet with two copies. That method was used ten years later by Bradbury and Evans (with electrotypes) for the wrappers of The Virginians.

37.

McKerrow, pp. 194-95, noted, for an earlier period, a dislike among printers for blank leaves.

38.

Graham Pollard, pp. 132ff, says that double impositions were introduced, as increased press sizes allowed, for the purpose of reducing presswork; hence, the increased presswork required by octavo imposition here seems unlikely.

39.

I used a photocopy of the copy in the Mitchell Memorial Library (Mississippi State University) to compare copies at the University of North Carolina, University of South Carolina, Duke University, Princeton University, and the Berg Collection, NYPL.

40.

In the British Library (1608/2920), the Fales Collection, NYU; and the personal possession of Mr. Nicholas Pickwoad. I wish to thank Mr. Pickwoad for his advice on the investigation of the alterations in the preliminaries.

41.

These figures are from the Bradbury and Evans ledgers kept at the Punch Office. The Smith, Elder accounts of stock received, kept at John Murray, Publishers, record the receipt of 1,039 copies - 1,020 in quires and 19 bound.

42.

Smith, Elder did not always discard Bradbury and Evans engraved title pages when reissuing the books. The single copies I have see, of the Smith, Elder reissues of the first edition of Pendennis and The Newcomes in 1866 both have new Smith, Elder titel pages but retain the engraved cities showing the Bradbury and Evans imprint.

43.

Zebulon Vance was governor of North Carolina, 1862-65 and 1876-79.

44.

It appeared as pp. 327 - 451 of Miscellanies, vol 4, and separately in paper wrappers as The History of Samuel Titmarsh and the Great Hoggarty Diamond. The sheets for both formats were printed from the same setting of type, but their pagination and signing differ.

45.

The History of Pendennis (London: Bradbury and Evans, Nov. 1848-Dec. 1850, twenty-four numbers in twenty-three parts, and 1849-50 in two volumes). My conclusions are based on the machine collation of five copies: three sets of parts and two book issues. In addition I have examined nine other copies.

46.

The Smith, Elder records show that Bradbury and Evans turned over 5,217 copies of various numbers in August 1865 to Smith, Elder, who printed 3,663 more numbers on 18 Oct. and 10 Dec. 1865. Not until 3 April 1866 is there a record that repairs were made in the stereotypes, after which 5,969 more numbers were printed. This gave a total of 14,849 numbers, which were bound into 613 copies of the novel, leaving only 111 numbes after having also sold 26 loose numbers. The plates of the first edition, not used again, were sold as old metal on 1 July 1868.

47.

For lack of a better term I have used "general impression" to mean the series of printings of separate numbers, often separated by months and even years, that constitutes a separate and distinguishable printing of the book as a whole. Thus, while the publisher's records indicate that number 2, for instance, was printed six times between 1848 and 1866, only three impressions of the book as a whole have been distinguished.

48.

The one copy of the book-form issue composed partially of sheets printed from type is the presentation copy to Peter Rackham in the Berg Collection, NYPL. Of the four sets of parts with some sheets printed from plates, two are in the British Library; one in the Cooper Library, University of South Carolina; and the fourth is in my own collection.

Many copies of Pendennis bound in two volumes without wrappers or advertisements were originally issued in parts and are distinguished front the book issue by the three stab holes in the gutter margins where the parts were sewn. Apparently this is not generally known: three of the seven copies of Pendennis in the Berg Collection, NYPL, described as "in book form" are actually bound sets of parts.

References:

Anesko, Michael. Friction in the Market: Henry James and the Profession of Authorship. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1986.

Barnes, James J. Free Trade in Books: A Study of the London Book Trade since 1800. Oxford, 1964.

Bolas, Thomas. Cantor Lectures on Stereotyping. London: W. Trounce, 1890

Bowers, Fredson. Principles of Bibliographical Description. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1949.

Bradbury, Henry. Printing: Its Dawn, Day and Destiny. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1858

Catalogue of an Exhibition of the Works of William Makepeace Thackeray…Held at the Library Co., of Philadelphia…1940. Philadelphia: priv. ptd., 1940.

Lewis Caroll and the House of Macmillan, eds. Cohen, Morton N. / Gandolfo, Anita. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1987.

Colby, Robert. Thackeray's Canvass of Humanity. Columbus: Ohio State Univ. Press, 1970.

Collins, A. S. The Profession of Lettes: A Study of the Relations of Authors to Patron, Publishers, and Public, 1780-1832. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1928.

Feltes, N. N. Modes of Production of Victorian Novels. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1986.

Fields, James T. Yesterdays with Authors. 1871; rpt. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1925.

Flamm, Dudley. Thackeray's Critics. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1967.

Gaskell, Philip. A New Introduction to Bibliography. London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1972.

Gettmann, Royal A. A Victorian Publisher: A Study of the Bentley Papers. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1960.

Glynn, Jenifer. Prince of Publishers: A Biography of George Smith. London: Allison and Busby, 1986.

Hagen, June Steffenson. Tennyson and His Publishers. London: Macmillan, 1979.

Hansard, T.C. Treatises on Printing and Type-Founding. From the seventh edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1841.

Harden, Edgar. "The Writing and Publication of Esmond" Studies in the Novel 13 (1981), 79-92.

Hepburn, James. The Author's Empty Purse and the Rise of the Literary Agent. London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1968.

Huxley, Leonard. The House of Smith, Elder. London: priv. ptd. 1923.

Knight, Charles. Passages of a Working Life during Half a Century: With a Prelude of Early Reminiscences. 3 vols. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1864-65.

Martin, Sir Theodore. Memoir of William Edmondstoune Aytoun. Edinburgh and London, n.d.

McKerrow, Ronald B. An Introduction to Bibliography. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928.

Mumby, Frank / Norrie, Ian. Publishing and Bookselling. London: Jonathan Cape, 1974

Mumby, Frank. The House of Routledge. London: Routledge, 1934.

Paston, George. At John Murray's: Records of a Literary Circle, 1843-1892. London: John Murray, 1932.

Patten, Robert. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. Oxford: Clarendon, 1978.

Plant, Marjorie. The English Book Trade: An Economic History of the Making and Sale of Books, 3r ed. London: Allen & Unwin, 1974.

Pollard, Graham. "Notes on the Size of Sheets". Library, 4thser. 22 (Sept.-Dec. 1941), 105-37.

Randall, David A. "Notes towards a Correct Collation of the First Edition of Vanity Fair", PBSA 42 (1948), 95-109.

The Letters and Private Papers of William Makepeace Thackeray, ed. Gordon N. Ray. 4 vols. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1946.

Ray, Gordon. Thackeray: The Uses of Adversity. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955.

-----. Thackeray: The Age of Wisdom. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1958.

Sadleir, Micheal. Trollope: A Bibliography. 1928, rpt. London: Dawsons, 1964.

Shillingsburg, Peter. "Thackeray and the Firm of Bradbury and Evans." Victorian Studies Association (of Ontario) Newsletter, no. 11 (March 1973), 11-14.

-----. "Detecting Stereotype Plate Usage in Mid-Nineteenth Century Books." Editorial Quarterly 1 (1975), 2-3.

-----. "Textual Introduction" to Vanity Fair. New York: Garland, 1989, 651-54.

Smith, Charles Manby. A Working Man's Way in the World: Being the Autobiography of a Journeyman Printer. London: William and F. Cash, n.d.

Southward, J. "Collection of MS. and Printed Matter relative to Stereotyping." St. Bride Technical Reference Library, London.

Sutherland, John. Victorian Novelists and Publishers. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1976.

Tillotson, Kathleen. "Oliver Twist in Three Volumes" Library 18 (1964), 113-32.

Van Duzer, Henry S. A Thackeray Library. 1919; rpt. New York: Kennikat Press, 1965.

Der Verlag Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1837-1912. Leipzig: Tauchnitz, 1912.

Vizetelly, Henry. Glances Back through Seventy Years. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Co., 1883.

Waugh, Arthur. A Hundred Years of Publishing: Being the Story of Chapman & Hall, Ltd. London: Chapman and Hall, 1930.

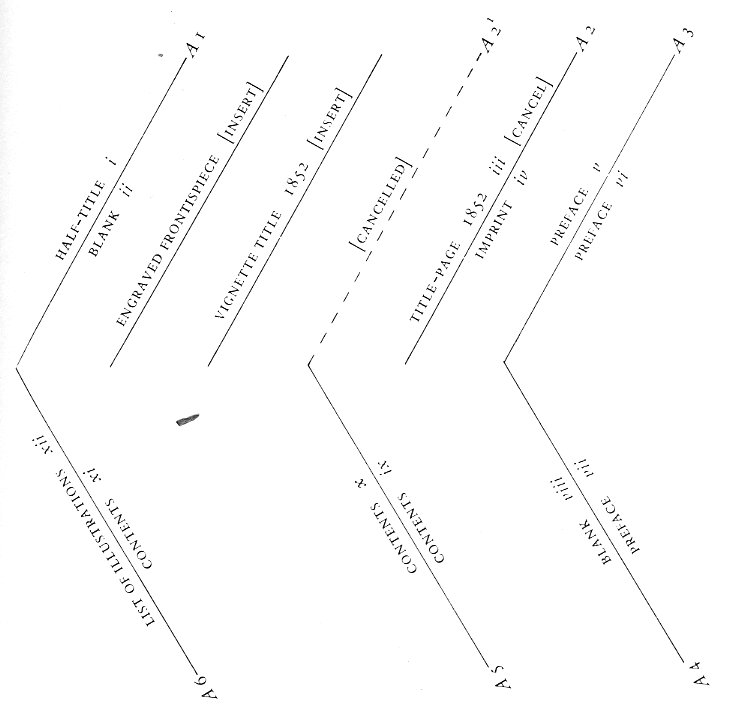

roduction processes affected single-volume publications in ways different from those attending serial publications. Though the importance of publisher's records in establishing printing history has long been recognized, the potential uses are exemplified particularly well in a study of the records for Thackeray's short novel The History of Samuel Titmarsh and the Great Hoggarty Diamond. Not only do these records reveal a hitherto unidentified edition of the book, but combining the information from the records with analytical examination of multiple copies of the books themselves reveals the processes of typesetting, stereotyping, imposition, pressruns, bindings, and sales of the book. As was the case with Vanity Fair, the total production picture has significance to textual analysis and gives insight into the influence of publishers on the book market as well as the book market's influence on publishers.

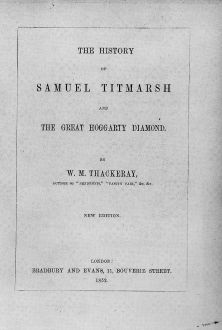

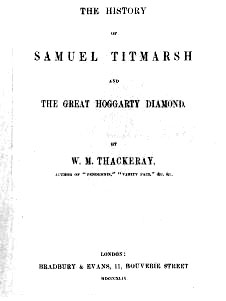

Thackeray wrote The History of Samuel Titmarsh in January and February 1841. He posted the manuscript to Bentley's Miscellany by 25 February and, having had no word from the publisher by June, reclaimed it rather angrily.29 It was first published in Fraser's Magazine in installments from September to December 1841. In June 1848 Thackeray, having just completed Vanity Fair, suggested to his publisher, Bradbury and Evans, that the firm reprint Samuel Titmarsh in book form. He wrote his mother the same month that he was to receive £100 for the reprint (Letters 2: 382). Although the first charges for Samuel Titmarsh in the Bradbury and Evans records are entered for 30 June 1848, the first edition in book form was the one published, without authorization, by Harper and Brothers of New [170/171] York in November or December 1848 as The Great Hoggarty Diamond. The first English edition, published by Bradbury and Evans, finally appeared in January 1849 (see figs. 1 and 2) and was followed immediately in February by a second edition from the same firm (see fig. 3)30. These two editions have always been referred to collectively as the first edition in book form (a label which ignores the New York edition) or the first English edition. The second of these two English editions, not selling well, was reissued with a new title page and slightly altered preliminaries by Bradbury and Evans in 1852 (see fig. 4) and then again in 1857 and finally by Smith, Elder and Company in 1872 (see fig 5). A fourth edition, published by Bernhard Tauchnitz, of Leipzig, may precede the second English edition, for its setting copy consisted of proof sheets from the first English edition sent from Bradbury and Evans to Williams and Norgate, Tauchnitz's British agents.31 Tauchnitz published the book together with The Book of Snobs as Miscellanies: Prose and Verse, volume 1, in 1849. A fifth edition was issued in two formats simultaneously. It was published in 1857 by Bradbury and Evans separately in paper wrappers as The History of Samuel Titmarsh and the Great Hoggarty Diamond and in cloth as part of the contents of Miscellanies: Prose and Verse, volume 4, a title borrowed from the Tauchnitz firm. The sheets for both of these issues were printed from the same setting of type; but they represent separate printings, for their pagination and signing differ.

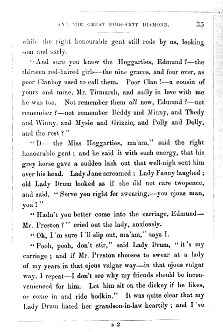

On the basis of publisher's records, I conjectured in 1973 the existence of an unrecognized English edition of The History of Samuel Titmarsh [Shillingsburg, Thackeray, p. 13]. Subsequently I found five copies and can show the distinctions between the two editions that had always been listed together simply as "London: Bradbury and Evans, 1849." The second of these editions went so long [171/172] undetected because its preliminary pages and last gathering of text are identical with those in the first English edition, and the rest is virtually a line-for-line resetting which imitates the first edition in every respect, suppressing anything that would easily call attention to itself.33 It is not surprising to find owners of the second edition who think they have the first: the covers are also replicas of the first-edition covers34.

According to the publisher's records, 2,000 copies of The History Of Samuel Titmarsh were printed on 27 January 1849. The records show charges of £40.5.6 for typesetting the first edition, but there is no entry for stereotyped plates. The record's next entry shows a printing of 2,000 more copies on 17 February, referred to as the second edition, entered this time at the cost of £36 for "composing and working" and adding charges for stereotyping. The obvious conclusions to draw are that stereotyped plates were not made for the first English edition, that most of the type was redistributed before a need for the second edition was recognized, and that type had to be recomposed for the second edition only twenty-one days after the printing of the first edition. Composition for the second edition was less expensive because the preliminary twelve pages and one gathering of text type were saved from the first edition for reuse and because line-for-line resetting was probably cheaper than typesetting from the magazine version. Ironically, sales of Samuel Titmarsh dwindled rapidly, and the [172/173]

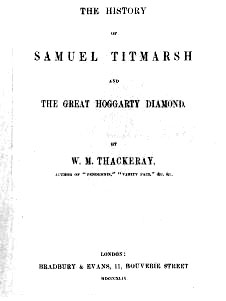

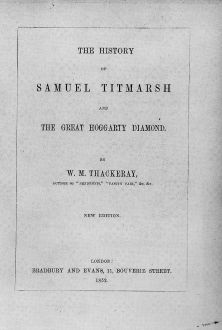

Fig. 1 (left) W. M. Thackeray's The History of Samuel Titmarsh ...

(London: Bradbury & Evans, 1849), first English edition, title page.

The second English edition, first issue, title page is identical. (Mitchell Memorial Library, Mississippi State University) [173/174]

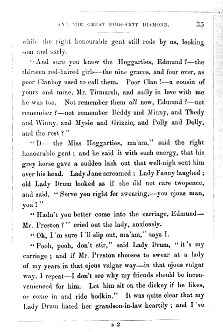

Fig. 2. (middle) W. M. Thackeray's The History of Samuel Titmarsh . . .

(London: Bradbury & Evans, 1849), first English edition, page 35.

(Mitchell Memorial Library, Mississippi State University) [174/175]

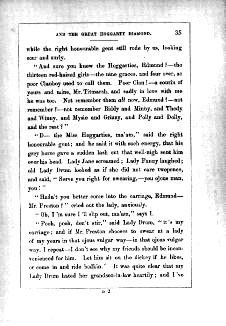

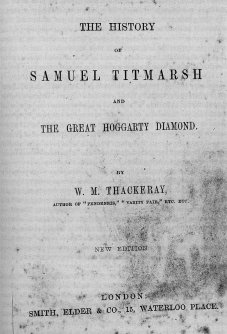

Fig. 3. (right)W. M. Thackeray's The History of Samuel Titmarsh . . .

(London: Bradbury & Evans, 1849), second English edition, page 35.

(British Library C.71.b.12)

[175/176]

|

Fig. 4. W. M. Thackeray's The History of Samuel Titmarsh . . .

(London: Bradbury & Evans, 1852), second English edition, second issue, title page.

(British Library 1608/2920)

[176/177]

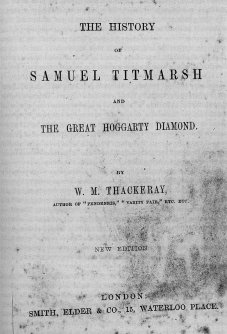

Fig. 5. W. M. Thackeray's The History of Samuel Titmarsh . . .

(London: Smith, Elder & Co, n.d.), second English edition, fourth issue, title page.

(North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) [177/178]

stereotypes from the second English edition were never used either by Bradbury and Evans or by Smith, Elder, which acquired them in 1865.

The publisher's records and an analysis of copies of the two 1849 editions of Samuel Titmarsh show how the books were produced, explain the carryover of the first-edition typesetting of the preliminaries And last gathering, expose the odd alterations made by Bradbury and Evans in 1852 for the second issue of the second edition, and demonstrate how Smith, Elder altered the remaining sheets for reissue in 1872.

The entry for the first edition on 27 January 1849 reads: "Printing 12 Sheets 12pp Sup Ryl 16° 2000; 6 Sheets @ 6.6. 12pp 2.9.6 40.5.6." Later the entry records a charge for twenty-six reams of paper. The entry shows that the twelve gatherings of the book's text were printed on super royal sheets of paper (measuring about 80 by 50 cm). The book itself measures about 17.7 by 12.4 cm per leaf, and each super royal sheet would make sixteen book leaves. Since the book's text is composed of twelve gatherings of eight leaves each, this means that each super royal sheet used in printing contained two gatherings of the book. Hence the reference to six sheets, since six sheets run through the press in 16mo imposition would produce twelve octavo sheets or gatherings for the book when properly cut apart. Composition of six sheets was charged at 16.6 each, or £37.16; there is an added charge of £2.9.6 for twelve pages (six leaves) of preliminaries, which makes the total cost of composition come to 140.5.6. This interpretation of the records is supported by the entry for paper. If one is to get 2,000 copies of a book which has twelve gatherings of eight leaves each and one preliminary gathering of six leaves from twenty-six reams of paper, one must get two gatherings from each sheet of paper. Figuring 26 reams x 500 sheets per ream = 13,000 sheets of paper / 13 gatherings per book = 1,000 copies, so that to get 2,000 copies, there must be 2 gatherings per sheet.

There are two ways this can be done. The sixteen pages of each gathering can be imposed so that both the inner and outer forms print together in the work-and-turn method, or the sixteen pages of the inner forms of two gatherings can be printed together and perfected by printing the outer forms of the same two gatherings.35 In both cases the sheets would be divided after printing. Each method requires the same amount of presswork, so neither method is more likely to have been used in this case. [178/179]

The entry for the second edition is complicated. Composition costs were entered at £36, as explained above. Stereotypes, costing £15.18.9, were entered for "six sheets 12pp." I have not seen stereotypes referred to as "sheets" before, and the plaster-cast method of stereotyping apparently used by the Bradbury and Evans printers at the time would not allow the production of a stereotyped plate of even octavo size, let alone any larger size that might explain the "six sheets" entry as a plate. It is most likely, therefore, that the "six sheets" refers to paper rather than to stereotyped plates. If so, six sheets is the right number necessary for the text of the book (plus the "12pp." of prelims) if it was imposed as 16mo for division into octavo gatherings after printing. The key to the problem, as with the first edition, is that according to the ledger the number of reams of paper required for the 2,000-copy pressrun was twenty-six. The price of stereotyping is given as £2.10 per sheet, for £15, but the total cost is given as if £15.18.9, so the twelve pages of preliminaries must have cost 18s.9d. in cast.

The mutual carryover of the typesetting for gathering N and the preliminaries seems to indicate that the call for the second edition came after the type from signature M and all preceding gatherings of the text had been distributed but before distribution of type from N or the prelims was begun. It seems also to indicate that each gathering was printed separately on 16mo sheets, each sheet producing two copies of the same gathering. Otherwise, one would expect both M and N to be carried over. It seems certain, in any case, that the second edition was printed from type before the stereotypes were cast, for there is no characteristic shrinkage of the type page in printed copies of the second edition.

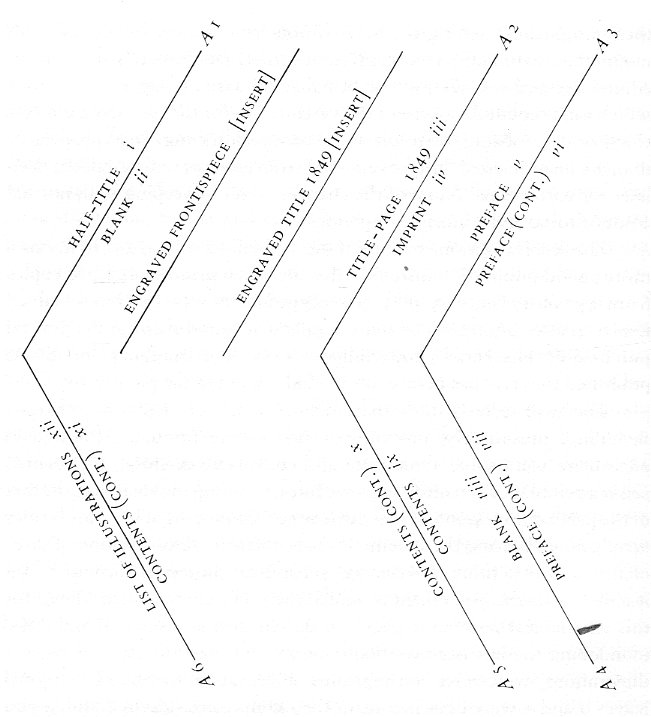

That the preliminaries were imposed in eights even though only a six-leaf gathering was bound into the book is highly probable. There is no indication in the records that paper of a different size was used. And a six-leaf gathering could be made more easily by printing an octavo and stripping away the outer fold than by printing quartos and folios to be united or even 12mos to be separated and the parts united. Neither machine collations nor charges for composition and stereotyping, in so far as they can be seen to apply to the preliminaries, give any reason to suspect duplicate settings run simultaneously.36 Furthermore, the ragged top edges of A3 and A4 (the central fold in the prelims) have no interlocking partners in any copies examined; these two leaves in a normally folded octavo would [179/180] have been joined by their top edges to the outermost leaves- It seems clear, then, that the preliminary gathering was an octavo with its outer conjugate leaves stripped away. I do not know to what extent it was normal in a printing house to allow the wastage of four pages per gathering, but it is possible that these cast-off leaves were used for advertisements or for some other purpose unconnected with The History of Samuel Titmarsh37. Assuming, in any case, that the paper for the first edition preliminaries was of the same size as that for the rest of the book, one possible procedure would have been to cut two reams in half and print the resulting 2,000 sheets in an octavo imposition. This would have the disadvantage of doubling presswork (i.e., as much presswork for one gathering as was necessary for a sheet of two gatherings elsewhere).38 The most likely possibility is that preliminaries were imposed as two half sheets of 16mo for printing by the work-and-turn method.

The first English edition of Samuel Titmarsh existed, then, in a single printing of 2,000 copies. This accounts, in part, for its rarity and for the difficulty of procuring copies for machine collation. Spot collation of several copies under difficult conditions revealed no variants within the first edition.39 A representative sampling of the features that distinguish the first edition from its look-alike second edition are recorded in Appendix D, table 1. Examination of the textual variants leads one to suspect that though there are a few new readings that are superior and which one might like to see retained in a new edition, nevertheless, none of the changes is authorial. In the absence of external evidence, this conclusion is corroborated though not proven, I believe, by two bibliographical facts. First, though there are textual variants in every reset gathering, no alterations appear in the preliminaries or in signature N. It seems likely that if Thackeray were responsible for the changes, he would be as anxious to alter readings in these two gatherings as in the reset ones. Second, if my analysis of the printing procedure for the second edition is anywhere near accurate and since some speed was evidently required in its production, [180/181] then compositors setting the new edition from a copy of the old with instructions to imitate its line configuration (so that ultimately signature N could be reused as it was) would be liable, by haste, to lapses of memory which can account for many of the variants. As for the rest, even the best changes are probably the result of the compositors' ingrained propensity to make unauthorized "improvements', in an attempt to forestall the need later for corrections. None of the changes is out of keeping with normal compositorial and editorial tampering.

The second edition, because it did not sell as well as the first, has a more varied publication history. After the initial printing of 2,000 copies from type on 17 February 1849, stereotyped plates were cast but remained idle even after Smith, Elder and Company acquired them in the general purchase of Thackeray's copyrights in 1865. But Bradbury and Evans published two reissues before Smith, Elder entered the picture.

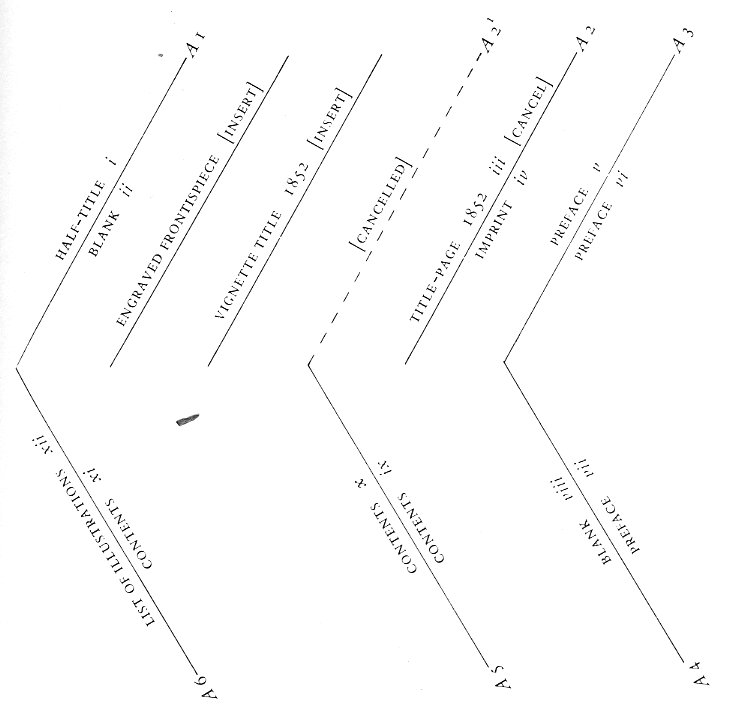

The 1849 records show that only 3,500 sets of illustrating plates - including, presumably, the vignette title - were printed. Although in 1852 there were some 1,700 unbound copies still in stock, the records show a printing of 500 more vignette titles, bringing the total to equal that of the printed text, 4,000. At the same time 1,000 copies of letter press titles

were printed bearing the statement "NEW EDITION." Examination of three copies with 1852 title pages (see fig. 4) confirms the ledger account.40 But it also reveals the odd extent to which the preliminaries were altered for this reissue: leaf 2 (the title page and the imprint on its verso) and leaf 6 (containing the last page of the list of contents and the page listing the illustrations) were reset and reprinted as conjugate leaves. The original leaves 2 and 6 were detached from their conjugates (leaves 1 and 5) and discarded. The new conjugate leaves 2 and 6 were inserted and the old leaves 1 and 5 were tipped in along with the frontispiece and vignette title. The reason for this apparently inefficient operation remains something of a mystery. No textual changes were required or effected in leaf 6. (For other changes, see Appendix D, table 2). Perhaps it was seen as desirable for binding purposes to have the two remaining conjugate leaves in the gathering next to each other rather than separated by the two tipped-in plates, new title page, and (now loose) leaf 5. The original binding arrangement, the 1852 arrangement, and the one that was avoided can be seen in figures, 6, 7, and 8. [181/182]

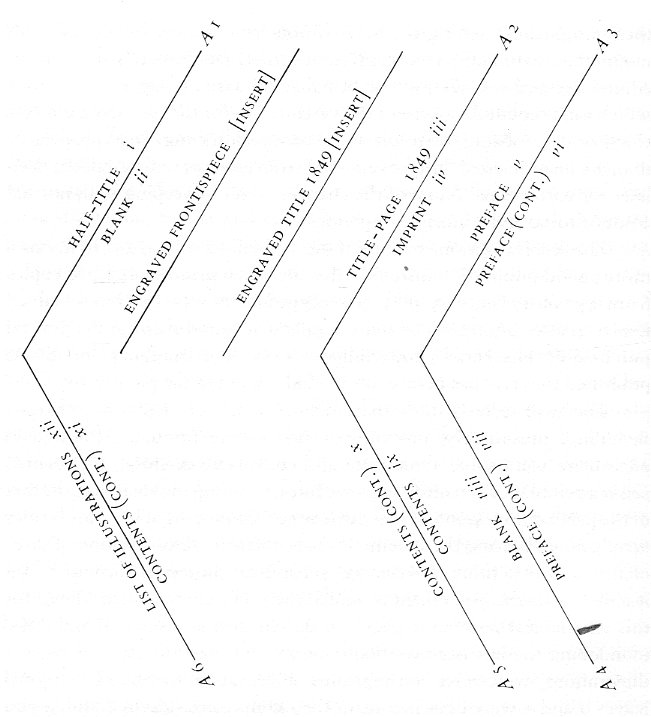

Fig. 6. First issue of the second English edition preliminaries, 1849. This is a six-leaf gathering with the engraved frontispiece and engraved title inserted following the first leaf. This format is identical with that in the first English edition. [Click on diagram to enlarge it.]

By January 1852 when the first print order for 1,000 copies of the title page went in, there were just over 1,700 copies of the book in stock. It follows that at least 700 copies retained the 1849 title page. In 1857 when the next print order for titles went in, the stock had been reduced by about 400 to 1,300 copies. One would assume that those 400 odd copies bore the 1852, rather than the old 1849, title page.

A print order for 200 titles came in October 1857. 1 have seen no copies to determine the extent of alteration, but presumably they bear an 1857 date. There is, of course, no way to know if these replaced copies [182/183]

Fig 7. This arrangement represents what would have happened in 1852 had only the title page been reprinted and tipped in in place of the original. [Click on diagram to enlarge it.]

Note that four single leaves would have occurred between the inner and outer folds

with 1852 or 1849 title pages. By 23 June 1865 over 260 more copies had been sold, no doubt depleting all stock of 1857 titles. There remained unsold, at the last Bradbury and Evans accounting, 1,035 copies, of which 1,019 were in unbound quires.41[183/184]

Fig. 8. Second issue of the second English edition preliminaries, 1852. [Click on diagram to enlarge it.] The second and sixth leaves have been replaced by conjugate cancels. This arrangement allows some of the strain of the inserts to be borne by the front free endpaper, thus reducing it on the sewing through the inner margin. It cannot, however, be known if this was the reason for the procedure followed. No textual changes were made in resetting leaf six.

The fourth issue by Smith, Elder in 1872 repeats this arrangement, except that the one copy I have seen omits the vignette title. I have seen no copy of the third issue, by Bradbury and Evans in 1857.

[184/185]

According to the Smith, Elder records, between August 1865 and January 1872 that company issued just over 200 copies using Bradbury and Evans title pages. In 1872 , with 811 copies still on hand, printed 800 undated cancel titles with their own imprint and again the imprecise statement "NEW EDITION." The one copy I have seen lacks the vignette title, which may have been omitted because it bore a dated Bradbury and Evans imprint.42. The Bradbury and Evans imprint at the foot of page 190 remained unchanged: replacing it would have required reprinting a whole gathering or the bother of a cancel. In 1879 the last 538 copies were remaindered to Reeves and Turner for just over 2d. per copy. The original publisher's price was 4s. 11d. This issue had not attracted collectors; the only copy I have seen (in the North Carolina Collection of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library; see fig. 5) was acquired because of the Zebulon Vance autograph on the flyleaf.43

With no known copies of the 1857 reissue and only one copy of the Smith, Elder undated but probably 1872 reissue, it is impossible to make general statements about the form the preliminaries took in these issues.

But the Smith, Elder issue apparently repeated the form at of the 1852 issue (see fig. 8). While it is likely that the 1857 titles were sold out before Smith, Elder purchased the stock and rights in 1865, there would have been some of the 1852 titles left at the time. Whether the 1852 format was imitated to facilitate rise of front matter already altered in 1852, or if binding requirements again were the deciding factor, I do not know. In any case the new title page is conjugate with A6 (pp. xi and xii), which therefore also had to be reset and reprinted. The changes introduced in the 1872 prelims are recorded in Appendix D, table 3.

It is fortunate that analytical bibliography need not justify itself by its usefulness to textual criticism, for the preceding discussion far exceeds the needs of that discipline, and the variants between the first and second edition are of negligible textual importance - unless the unsuspecting editor were to work at the British Library or the Library Company of Philadelphia, which have only the second edition looking very like the first. The variants between the first, second, and fourth issues of the second edition are of no textual significance whatsoever. They do, [185/186] however, illustrate a point about the reputation of the book itself as well as of its author: 2,000 enthusiastic readers of Vanity Fair grabbed up the new offerings, and then it took thirty years to dispose of the remaining 2,000 copies. Nevertheless, in 1857 the same publisher who was having such a hard time moving the books he already had in stock brought out a new edition of Samuel Titmarsh in two different formats.44 The success of that seemingly bold venture demonstrated the existence of alternative markets; the reprints did not simply reach more of the same market targeted by the first edition.

Victorian

Web

Authors

W. M.

Thackeray

Contents

Next

Section

Last modified 30 November 2021

|