lthough

Alan Watts' article in The Dickens Magazine (in the first

series, devoted entirely to Great Expectations) as to why Great Expectations was not illustrated is correct with respect to

Dickens, I cannot agree with his larger claim, namely that the age of the illustrated

book was coming to an end. For instance, J. A. Hammerton in The

Dickens Picture-Book (1910) asserts that the later illustrated editions of Dickens

produced by A. B. Houghton,

G. J. Pinwell,

Fred Walker, and the brothers

Dalziel are equal in quality

to any of those illustrated by

Phiz and

Leech. Watts's conclusion is

particularly misleading in that the golden age of illustrated fiction was not over — in

fact, if one is an aficionado of the nineteenth-century illustrated British magazine, one

might argue that such a golden age was just about to begin as Dickens published the first

instalment of Great Expectations in December, 1860, in All the Year Round. A complete listing of serial instalments and

their relationship to chapters in the volume publications for many Victorian novelists —

including Thomas Hardy and

Wilkie Collins — is given by J. Don Vann in Victorian Novels in Serial (New York: MLA, 1985); Vann shows that

serialisation of novels continued well past the 1860s — and many of these later

nineteenth-century novels were illustrated. While it is true that monthly

part-publication was becoming a thing of the past, the new illustrated magazines,

which began in the 1860s, including Good Words,

Belgravia, and

The

Graphic, would bring some of the Victorian period's greatest writers cheaply

into British homes, accompanied by plates produced by such notable graphic artists as

Arthur Hopkins,

Hubert Von Herkomer, and

Robert Barnes (not to mention

Sol Eytinge and

John McLenan in the United

States. The age of the illustrated book was hardly over by 1861.

lthough

Alan Watts' article in The Dickens Magazine (in the first

series, devoted entirely to Great Expectations) as to why Great Expectations was not illustrated is correct with respect to

Dickens, I cannot agree with his larger claim, namely that the age of the illustrated

book was coming to an end. For instance, J. A. Hammerton in The

Dickens Picture-Book (1910) asserts that the later illustrated editions of Dickens

produced by A. B. Houghton,

G. J. Pinwell,

Fred Walker, and the brothers

Dalziel are equal in quality

to any of those illustrated by

Phiz and

Leech. Watts's conclusion is

particularly misleading in that the golden age of illustrated fiction was not over — in

fact, if one is an aficionado of the nineteenth-century illustrated British magazine, one

might argue that such a golden age was just about to begin as Dickens published the first

instalment of Great Expectations in December, 1860, in All the Year Round. A complete listing of serial instalments and

their relationship to chapters in the volume publications for many Victorian novelists —

including Thomas Hardy and

Wilkie Collins — is given by J. Don Vann in Victorian Novels in Serial (New York: MLA, 1985); Vann shows that

serialisation of novels continued well past the 1860s — and many of these later

nineteenth-century novels were illustrated. While it is true that monthly

part-publication was becoming a thing of the past, the new illustrated magazines,

which began in the 1860s, including Good Words,

Belgravia, and

The

Graphic, would bring some of the Victorian period's greatest writers cheaply

into British homes, accompanied by plates produced by such notable graphic artists as

Arthur Hopkins,

Hubert Von Herkomer, and

Robert Barnes (not to mention

Sol Eytinge and

John McLenan in the United

States. The age of the illustrated book was hardly over by 1861.

Consider Hardy's literary output as an example. Many of Hardy's short stories appeared first in illustrated periodicals such as Harper's Weekly in America and The Graphic in Britain. Furthermore, of Hardy's fourteen Novels of Character and Environment, only the first two — Desperate Remedies (1871) and Under The Greenwood Tree (1872) — were first published in volume form. For the most part, Hardy first brought out his novels in monthly instalments in British literary magazines; only three were published in weekly numbers, and only two — Two on a Tower (1882) and The Woodlanders (1886-7) were published without illustration since the magazines in which those novels first appeared (The Atlantic Monthly and Macmillan's Magazine) were not illustrated. It would more accurate to assert that, after the publication of A Tale of Two Cities (1859) in his own — unillustrated and therefore quite inexpensive — All the Year Round, Dickens failed to grasp the new direction that illustrated fiction was taking: Once a Week was founded in 1859, The Cornhill and Good Words in 1860, whereas The Graphic appeared in 1869.

Although several possible explanations may account the “falling-off" (131) in quality which Michael Steig among others detects in the sequence for the 1859 novel, he speculates that, owing to the novelist's growing lack of interest in illustration, Dickens provided "Browne less interesting subjects and relatively little guidance. Perhaps another factor was that A Tale of Two Cities was written expressly for weekly part publication in All the Year Round, and it is thus unusually compressed in its bulk and schematic in its plan and development" (Steig, 312). Much of Browne's work involves contemporary settings and characters in nineteenth-century costume, so that, as Percy Muir uncharitably remarks of his work for A Tale of Two Cities, "The figures look like characters in a masquerade and not very convincing ones at that" (96). Muir and Steig concur in their explanation for this inferior narrative series: "The sad fact is that the poor man's powers were declining" (Muir, 97). Like Alan S. Watts in "Why Wasn't Great Expectations Illustrated?" Steig attributes Dickens's abandonment of his principal illustrator of twenty-three years, Phiz, as symptomatic of Dickens's attitudes towards pictorial accompaniment by the end of the 1850s: "The fact is that Dickens no longer felt the need for illustrations" (Watts, 8) because "the days of illustrated novels were drawing to an end, and possibly Dickens foresaw this" (Watts, 9).

Had Dickens wanted illustrations [after severing his connection with Browne] he would have had to seek out a new collaborator, a search made difficult by the marked change in style and use of book illustrations in the late fifties. The familiarity of the subject matter in the new realistic fiction and the growing sophistication of the reading public made illustrators less essential to the novels of the 1860s than they had been to the novels of the forties and fifties. (Davis, 139)

On the other hand, Muir like A. J. Hammerton suggests that “Dickens felt the need of new blood" (97) in illustrating reat Expectations . Certainly on the eve of his second American reading tour Dickens seems quite interested in the numerous Sol Eytinge and Sir John Gilbert illustrations intended to accompany A Holiday Romance in Our Young Folks: "They are remarkable for a most agreeable absence of exaggeration, a pleasant sense of beauty, and a general modesty and propriety which I greatly like" ("To J. T. Fields, 2 April 1867"). Although this letter to the novelist's American publisher in Boston may suggest Dickens's desire to stay current with popular taste, the Eytinge vignettes for A Holiday Romance are hardly the "austere" (11) and serious productions that Steig asserts are characteristic of 1860s illustrators.

Finally, in "To Edward Chapman, 16 Oct. 1859" Dickens complains to his publisher: "I have not yet seen any sketches from Mr. Browne for No. 6 [to be published 31 Oct.]. Will you see to this, without loss of time" (Letters, Vol. 9: 136). The Pilgrim editors note that Dickens

may have felt that Browne was dilatory and have resented the fact that he was simultaneously providing numerous illustrations for Once A Week. When the book was published as a volume, CD had his own copy bound without the plates.

The rival weekly was one of the new, illustrated sort, and the other serialised novel on which Phiz had been working was Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn (1857-59), the plates for which Steig pronounces "more interesting than those for Dickens's novel" because of their incisive lines “greater attention to detail, and a depiction of human figures which is charged with life and energy" (312). Dickens may well have felt that Phiz's superior work for Once A Week was preventing the illustrator from adhering to Chapman and Hall's publishing deadlines for the monthly numbers of Tale, and that Phiz was failing to clear his conceptions at the draft stage with the novelist, who valued the opportunity to suggest alterations.

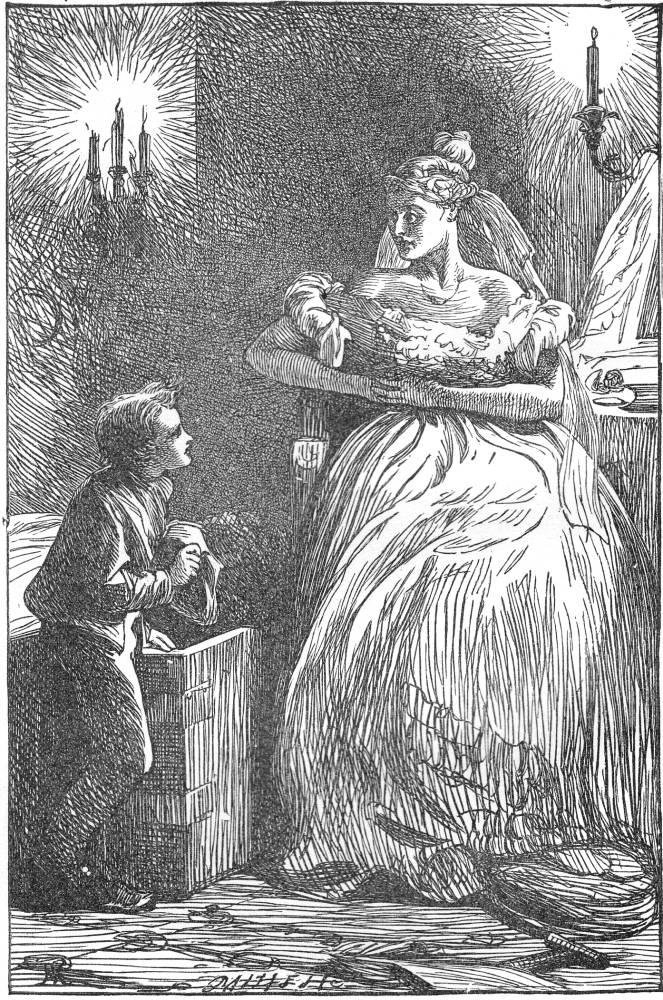

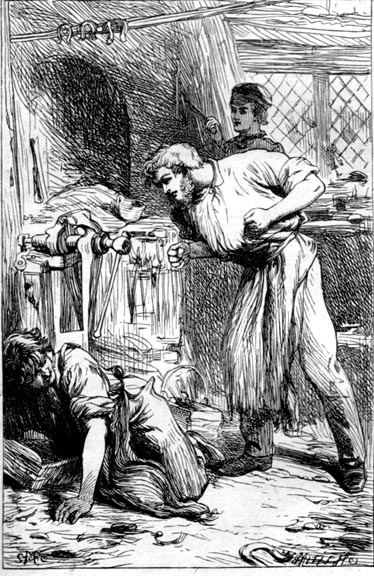

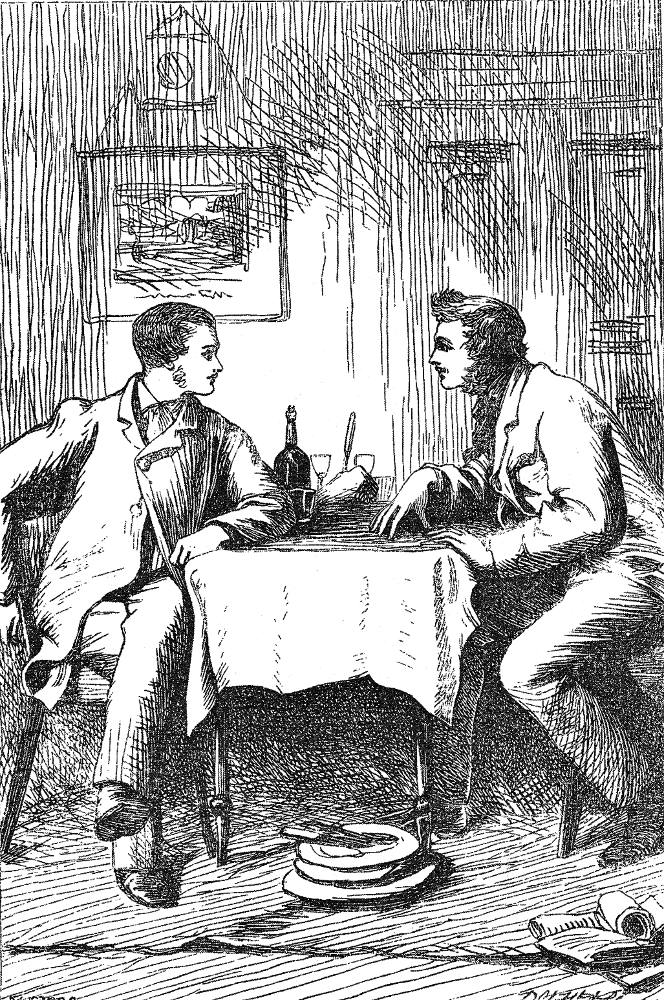

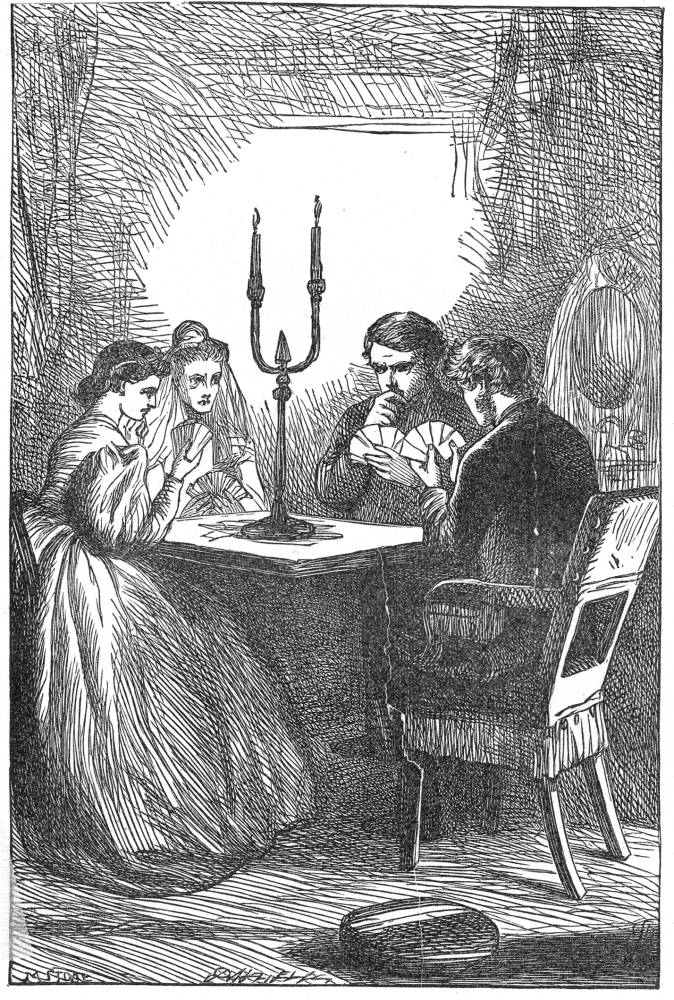

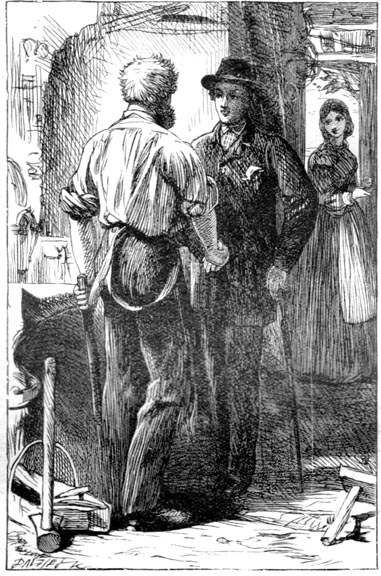

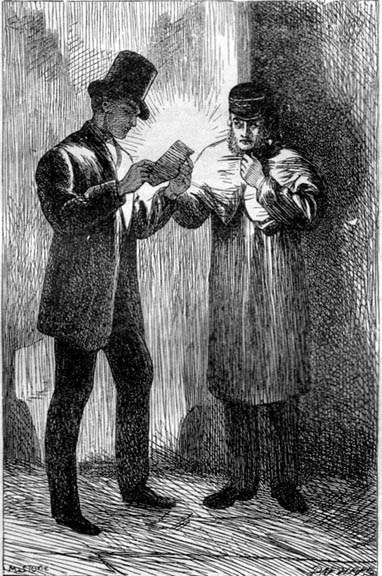

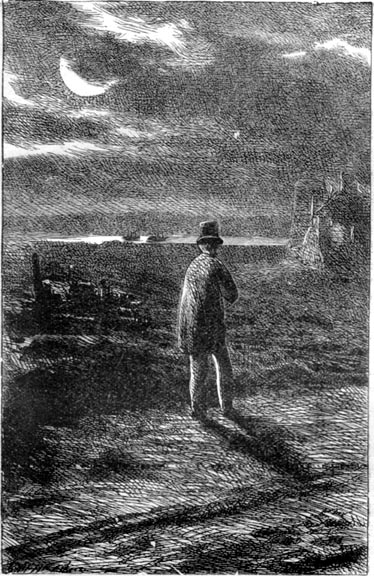

Marcus Stone's Eight Commissioned Wood-engravings for the Illustrated Library Edition (1862)

Other Artists’ Illustrations for Dickens's Great Expectations (1860-1910)

- Edward Ardizzone (2 plates selected)

- H. M. Brock (8 lithographs)

- Felix O. C. Darley (2 plates)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (8 wood engravings)

- F. A. Fraser in the Household Edition (1876) (30 wood-engravings)

- Harry Furniss (28 plates)

- Charles Green (10 lithographs)

- John McLenan (40 wood engravings)

- Frederic W. Pailthorpe (21 lithographs)

Related Materials

- A Comparison of Fraser's Illustrations in the original 1876 Household Edition plates and those in the Collier New York edition of 1900

- Great Expectations in Film and Television, 1917 to 2000: The Novel's Culminating Scene in Two Notable Film Adaptations (1921 and 1946)

- Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations

- Bibliography of works relevant to illustrations of Great Expectations

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Illustrations for Great Expectations in Harper's Weekly (1860-61) and in the Illustrated Library Edition (1862) — 'Reading by the Light of Illustration'." Dickens Studies Annual, Vol. 40 (2009): 113-169.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Allingham, Philip V. “We Can Now See That the Days of Illustrated Novels Were Drawing to an End" — Not So." The Dickens Magazine. Haslemere, Surrey: Bishops Printers. Series 1, Issue 3, pp. 6-7.

Browne, Edgar. Phiz and Dickens As They Appeared to Edgar Browne . London: James Nisbet, 1913.

Buchanan-Brown, John. Phiz! The Book Illustrations of Hablot Knight Browne. Newton Abbot, London, and Vancouver: David and Charles, 1978.

Cayzer, Elizabeth. 'Dickens and His Late Illustrators. A Change in Style: Phiz and A Tale of Two Cities." Dickensian 86, 3 (Autumn, 1990): 130-141.

Davis, Paul B. 'Dickens, Hogarth, and the Illustrations for Great Expectations ." Dickensian 80, 3 (Autumn, 1984): 130-143.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Hughes, Linda K, and Lund, Michael. The Victorian Serial. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. New Totowa, Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981).

Johannsen, Albert. Phiz: Illustrations from the Novels of Charles Dickens . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956.

Leavis, F. R. and Q. D. 'The Dickens Illustrators: Their Functions." Dickens the Novelist. London: Chatto and Windus, 1970. Pp. 332- 371.

The Letters of Charles Dickens . General editors Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Vol. 9 (1859-1861), ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1997. Vol. 11 (1865-1867), ed. Graham Storey. Oxford: Clarendon, 1999.

Meisel, Martin. Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983.

Muir, Percy. Victorian Illustrated Books . London: B. T. Batsford, 1971.

Solberg, Sarah A. "A Note on Phiz's Dark Plates." Dickensian 76, 1 (1980): 40-41.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Watts, Alan S. "Why Wasn't Great Expectations Illustrated?" The Dickens Magazine. Haslemere, Surrey: Bishops Printers. Series 1, Issue 2, pp. 8-9.

Created 27 June 2007 Last modified 2 November 2021