Old Orlick Among the Cinders

Marcus Stone

1862

13.2 cm high by 8.8 cm wide (5 ⅛ by 3 ½ inches) framed

Third illustration for Great Expectations, facing p. 132.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Marcus Stone —> Next]

Old Orlick Among the Cinders

Marcus Stone

1862

13.2 cm high by 8.8 cm wide (5 ⅛ by 3 ½ inches) framed

Third illustration for Great Expectations, facing p. 132.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

If any man in that neighbourhood could stand up long against Joe, I never saw the man. Orlick, as if he had been of no more account that the pale young gentleman, was very soon among the coal dust, and in no hurry to come out of it. (Ch. 15, p. 132) [illustration appears on p. xiv in the Nonesuch Edition rpt. 2005].

All eight of Marcus Stone's full-page wood-engravings present Philip Pirrip ("Pip") in some form on the picaresque high road from the Marshes to London and on the life journey from blacksmith's apprentice to a very different identity in terms of class and profession. Here, Pip in his cloth cap, marker of his class, watches from rear centre as the giants, Joe and Orlick, struggle after Orlick has insulted Mrs. Joe. Like the other noted Dickens first-person narrator, David Copperfield, Pip is, in fact, often an observer and reporter, as well as the story's protagonist and the consciousness through which the actions, speeches, and observations of the novel are filtered. The plate is much more effectively positioned in the original Chapman and Hall volume, immediately opposite the passage realised, than it is reproduced and repositioned in the Nonesuch Edition (1937; rpt., 2005). In Marcus Stone's Old Orlick Among the Cinders, we can identify ourselves with the figure of Pip because Stone has depicted him as a spectator, although each picture's perspective is established as belonging to a detached viewer who regards Pip as he in turn looks at Miss Havisham in Pip Waits on Miss Havisham and Joe and Orlick in this forge scene.

Mature Pip as storyteller, as observer and recorder of events from his first meaningful encounter in life — with the escaped convict Magwitch in the churchyard — is once again dwarfed by the other actors in the scene in the latter woodcut, but here his expression is critical rather than adoring. Although neither illustration contains as much detail as the Browne and Cruickshank steel engravings that adorn the earlier Dickens novels, each contains a significant object with thematic associations: the former plate includes Miss Havisham's disregarded timepiece (to the right of her left elbow), and the latter plate shows a vice, suggestive of Pip's position in the argument that has erupted between Joe, Mrs. Joe, and Orlick over the protagonist's taking time off to visit Satis House.

In the 1860-61 Harper's Weekly wood-engravings, John McLenan has given his villainous journeyman gaiters rather than cowboy boots, but the desperado's eyes in particular betray a style more geared towards caricature than realism. Stone's fallen Orlick, in the foreground (left) of Old Orlick Among the Cinders, which serves as the frontispiece for the new Nonesuch Edition, is far more plausible and decidedly younger than McLenan's oddly-attired figure. Stone renders Orlick a more suitable "double" psychologically for Pip, who also appears in working-class garb in the two Stone plates that precede Pip's coming into his expectations. McLenan's Orlick lacks the dynamic nature and sheer physicality of Stone's rebellious journeyman. McLenan's, in contrast, looking more like a waxworks dummy of a Western desperado than a representative of the tradition of the melodramatic lower-class villain, epitomised somewhat later by Dick Dead-Eye in Gilbert and Sullivan's H. M. S. Pinafore.

Stone consistently depicts Joe as a blonde, bearded, Nordic giant presiding over his forge and menacing Orlick, restraining the power in his mighty arms by a supreme act of self-control. Moreover, whereas Stone's renditions of Pip (in Pip Waits on Miss Havisham and Old Orlick Among the Cinders) interpret him as a "labouring boy," McLenan consistently depicts young Pip in thoroughly respectable, American middle-class costume. For example, in Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This Is Kind! (1 Dec. 1860, p. 765), Pip is wearing a shirt with a broad collar, a short jacket with large buttons, matching trousers, and shoes (rather than working-class boots), his garb seeming consistent with Mrs. Joe's American-middle class hooped skirt, bonnet, and shoulder-covering, all suitable to the 1860s rather than the 1830s.

Charles Green's 1897 illustration of precisely the same scene of confrontation in the forge, a smooth lithograph showing a somewhat leaner and less physically powerful Joe, Orlick . . . very soon among the coal-dust, effectively conveys a sense of the blacksmith's shop. Green establishes gives a more mature Pip's position relative to those of the combatants. However, despite its highly convincing detailism, the 1897 lithograph lacks the sheer energy of Stone's conception of the confrontation.

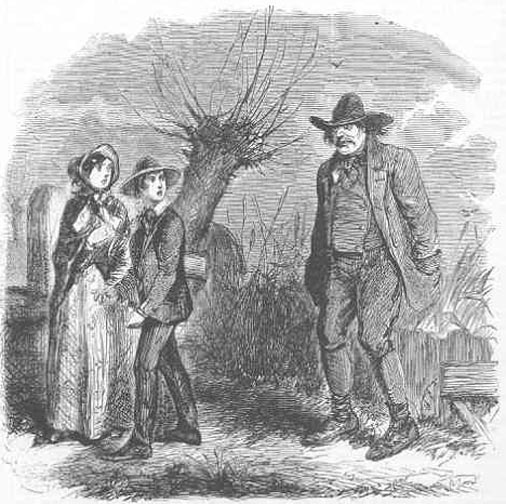

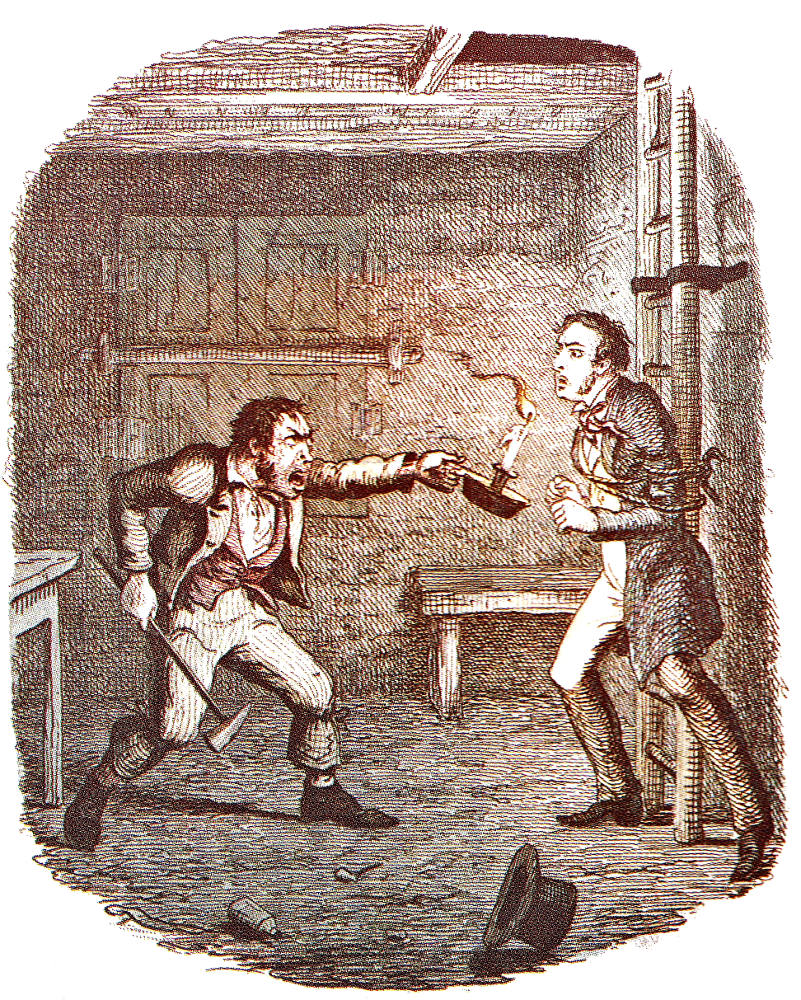

Left: John McLenan's 2 February 1861 depiction of Orlick's meeting Pip and Biddy on the Marshes, perhaps not accidentally; "Hulloa!" he growled; "Where are you two going?". Middle: Old Orlick by Sol Eytinge, Junior in the Diamond Edition (1867), which involves a more sinister and knowing villain menacingly wielding a sledge-hammer. Right: Charles Green's Gadshill Edition lithograph of the blacksmith and his assistants in the forge, "Orlick . . . very soon among the coal-dust" (1897).

=

=

Left: F. A. Fraser's Household Edition illustration of the same scene, but a marginalised rather than central Pip, in ""Orlick . . . . was very soon among the coal-dust, and in no hurry to come out of it" (1876). Centre: F. W. Pailthorpe effectively communicates Orlick's descent into madness in Old Orlick means murder (1885). Right: Harry Furniss's portrait of a far less physically intimidating Orlick, but with a posture, gait, and shiftiness of the eyes suggestive of duplicity, "Dolge Orlick" (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Allingham, Philip V. "The Illustrations for Great Expectations in Harper's Weekly (1860-61) and in the Illustrated Library Edition (1862) — 'Reading by the Light of Illustration'." Dickens Studies Annual, Vol. 40 (2009): 113-169.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. 9 (1859-1861).

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. All the Year Round. Vols. IV and V. 1 December 1860 through 3 August 1861.

Dickens, Charles. ("Boz."). Great Expectations. With thirty-four illustrations from original designs by John McLenan. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson (by agreement with Harper & Bros., New York), 1861.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. Marcus Stone. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1862. Rpt. in The Nonesuch Dickens, Great Expectations and Hard Times. London: Nonesuch, 1937; Overlook and Worth Presses, 2005.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Volume 6 of the Household Edition. Il. F. A. Fraser. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. The Gadshill Edition. Il. Charles Green. London: Chapman and Hall, 1897-1908.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. "With 28 Original Plates by Harry Furniss." Volume 14 of the Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

McLenan, John, il. Charles Dickens's Great Expectations [the First American Edition]. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, Vols. IV: 740 through V: 495 (24 November 1860-3 August 1861). Rpt. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson, 1861.

Rosenberg, Edgar (ed.). "Launching Great Expectations." Charles Dickens's Great Expectations. New York: W. W. Norton, 1999. Pp. 389-423.

Waugh, Arthur. "Charles Dickens and His Illustrators." Retrospectus and Prospectus: The Nonesuch Dickens. London: Bloomsbury, 1937, rpt. 2003. Pp. 6-52.

Created 11 January 2014 Last updated 11 November 2021