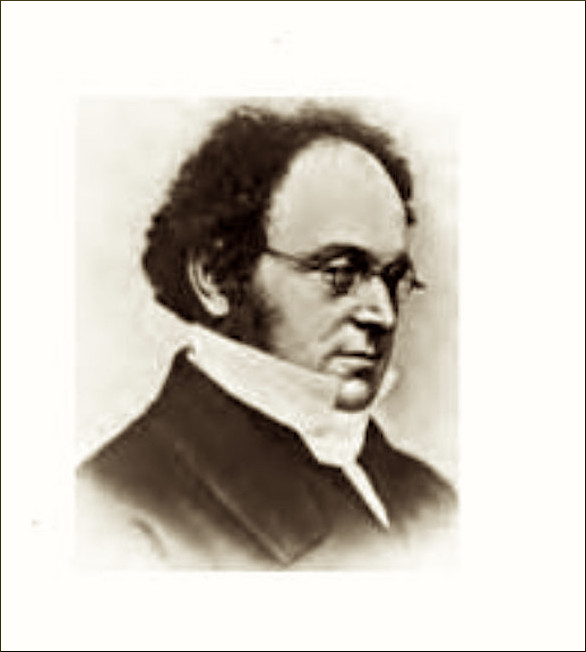

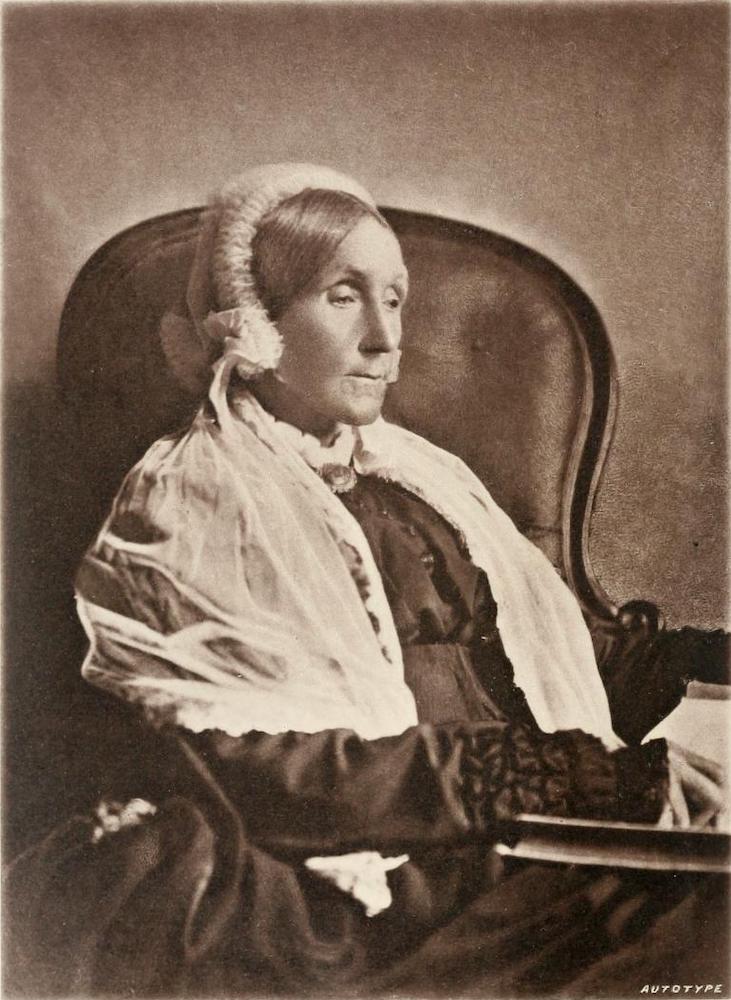

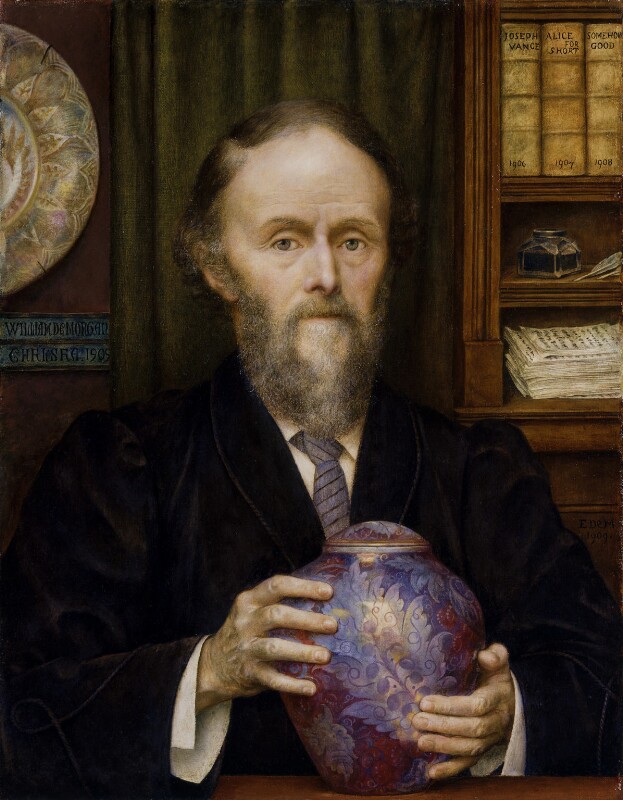

ary De Morgan was the fifth and youngest daughter of the renowned mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871), a prominent academic, and his wife Sophia Elizabeth (née Frend) (1809-1892) became "a pioneering women's rights campaigner," one of the signatories to the women's suffrage petition of 1866, and the author of "Our Better Selves," an essay urging better education for women (Rose, "The Feminist Network," 152). The eldest of Mary's three brothers, in the couple's typically large Victorian family of seven children, was the well-known Arts and Crafts ceramicist and stained-glass designer, William Frend De Morgan.

From left to right: (a) Augustus De Morgan (frontispiece of his wife's Memoir of him, from a photograph by Mayall, London). (b) Sophia De Morgan, from a photograph taken in 1886 (frontispiece of Sophia De Morgan's Reminiscences). (c) Portrait of William De Morgan by his wife, Evelyn De Morgan (click on this for more information).

By all accounts, Mary was lively, outspoken and generally outgoing. Anna Wilhelmina Stirling described her in 1922 as "a brusque, clever child," who grew into "a talented woman, who amused people by her witty sayings and quick repartees," adding that "[i]n appearance she was in marked contrast to her brother, being small and slight, with china-blue eyes and regular features, while her quick, sharp voice accentuated a somewhat abrupt manner" (105). After their father died in 1871, those of the family who were still at home, that is, just Sophia with her son William and his youngest sister Mary, moved from Primrose Hill in to Great Cheyne Row, Chelsea. Established here in 1872, Mary was now very much within the orbit of the key figures in the most important movements of the day. Her own talents flourished: most notably, she became "a journalist and author of exquisitely written tales illustrated by figures such as William De Morgan, Walter Crane, and Olive Cockerell, ... an expert embroiderer who worked alongside May Morris on the Kelmscott Manor bed hangings for William Morris" (Carroll 104). She also played an active part in social projects, such as visiting the East End slums and helping to put on concerts there. Following in her mother's footsteps, she joined the Women’s Franchise League, and in 1889 she signed the Declaration in Favour of Women’s Suffrage, along with her mother and her sister-in-law, the artist Evelyn De Morgan, whom William had married in 1887 (see Marilyn Pemberton's useful chronology, p. 8).

Despite her own achievements, until very recently Mary's own reputation has been almost submerged by the waves created by her more famous brother and his wife. Most standard reference books, like Joanne Shattock's Oxford Guide to British Women Writers (1993), and even the latest (7th) edition of The Cambridge Companion to English Literature (2009), edited by Dinah Birch, have passed over her. However, she has been remembered as a writer of quirky and subversive fairytales in accounts of children's literature, like Humphrey Carpenter and Mari Prichard's Oxford Companion to Children's Literature (corrected edition, 1995), and more recently she has attracted wider critical attention. This is especially so since the role of fairytales and fantasies in Victorian literature has been more fully understood: these were, after all, acceptable vehicles for authors as eminent as John Ruskin (The King of the Golden River, 1851) Charles Kingsley (The Water Babies, 1863) and George MacDonald (At the Back of the North Wind, 1871) to express their views, not simply to children but to adults as well. Her own tales in this genre, too, "offered de Morgan the unique opportunity to speak her mind without social condemnation" (Wagner 246).

Cover of The Wind Fairies, 1900.

Mary's mother was interested in spiritualism and had published From Matter to Spirit (1863); perhaps this contributed to her daughter's interest in otherworldly realms, and led to her interest in fantasy. At any rate, Mary began to entertain the Burne-Jones and Morris children, among others, with fairy stories, collecting these in written form, and publishing several books of them. Her first publication was co-authored with a friend, Edith Helen Dixon: Stories of Old SchoolFellows (1872). This was followed by her own On a Pincushion and other fairy tales (1877), which William himself illustrated for her, using a new method of his own invention. Next came two more collections under her own name, The Necklace of Princess Florimonde and other stories, this time illustrated by Walter Crane (1880), and The Wind Fairies and other tales (1900), dedicated to Edward Burne-Jones's grandchildren, Angela, Dennis and Clare Mackail, and illustrated by Olive Cockerell. She also wrote a novel for adults, under a title suggested by her brother,

In recent years, Mary has been accorded some standing as a feminist writer, because of the feminist twist to her quirky fairytales. The recent interest in periodical literaure has also drawn attention to her contributions of stories and articles to magazines. The articles were very far removed from any kind of fantasy, and show her political inclinations. They were on such topics as “Co-operation in England in 1889” in the Westminster Review of May 1890, and “The New Trades-Unionism and Socialism in England” in The Home-Maker, an American magazine, in January 1891. A good case has also been made out for her as an early environmentalist: "De Morgan's tales suggest an awareness of early green political issues, and often critique unsustainable ecological practices," describing magic involving "the powerful, often transformative elements of earth, air, fire, and water, as well as to green spaces" (Carroll 108). Such concerns are even apparent in her embroidery. Clearly, they formed an important element of her general outlook on life. One indication of her improved status is a recent play about her, written by Claire Parker (who also took the role of De Morgan herself), and first produced by the Lynchpin Theatre company in 2024. As Parker explains, its title, The Vegan Tigress, was inspired by "The Hair Tree" in On a Pincushion and other fairy tales, in which a woman is turned into a tigress and (if she hopes to return to her former shape again) not allowed to eat flesh. Nothing could better suggest how well De Morgan's ideas chime with those of our own age.

Left: Publicity photograph for The Vegan Tigress; right: Production photograph from the play (note the Suffragette colours, purple, white and green). Both photographs kindly provided by Lynchpin Theatre.

In November 1905 Mary De Morgan went out to Egypt to escape the British climate, and improve her health, but did not exactly live the life of an invalid there. As Stirling put it, "Threatened with phthisis, Mary De Morgan had been ordered to live abroad, and had subsequently undertaken a strange task which interested her greatly — the charge of a Reformatory for children in Cairo" (241). However, "bossing a reformatory of small female Arab waifs and strays," as her brother described it in a letter (qtd. in Stirling 253), may have been too much for her. She fell ill, was moved to the German hospital there, and passed away soon afterwards. Two days later (20 May 1907), she was buried in Cairo's British Protestant Cemetery. She was not tragically young, especially by the standards of her day, but still only 57.

Bibliography

Carroll, Alicia. “The Greening of Mary De Morgan: The Cultivating Woman and the Ecological Imaginary in ‘The Seeds of Love.’” Victorian Review 36. No. 2 (2010): 104–17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41413856.

Crawford, Alan. "Morgan, William Frend De (1839–1917), potter and novelist." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 23 February 2025.

De Morgan, Mary. The Windfairies and Other Tales. Illustrated by OLive Cockerell. London: Seeley, 1900. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Web. 1 March 2025.

De Morgan, Sophia Elizabeth. Memoir of Augustus De Morgan. London: Longmans, Green, and co., 1882. Internet Archive, from an unknown library. Web. 1 March 2025.

_____. Threescore years and Ten: Reminiscences of the Late Sophia Elizabeth De Morgan: to which are added letters to and from her husband, the late Augustus De Morgan, and others. London: Richard Bentley, 1895. Internet Archive, fromthe University of California Libraries. Web. 1 March 2025.

Parker, Claire, speaking in The Vegan Tigress: Mary De Morgan and Her Fairytales." Interview on the PreRaphaelite Society Podcast. https://www.pre-raphaelitesociety.org/podcast/episode/88e8c923/the-vegan-tigress-mary-de-morgan-and-her-fairy-tales.

Pemberton, Marilyn. Out of the Shadows: The Life and Works of Mary De Morgan. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012.

Rose, Lucy Ella. "The Feminist Network of Evelyn De Morgan." In Evelyn & William De Morgan: A Marriage of Arts and Crafts, edited by Margaretta S. Frederick. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2022. 149-57.

_____. "The Vegan Tigress: intimate play resurrects fierce forgotten Victorian writer." website">theconversation.com. Web. 1 March 2025. https://theconversation.com/the-vegan-tigress-intimate-play-resurrects-fierce-forgotten-victorian-writer-251179

Stirling, A.M.W. William De Morgan and his wife. London: Butterworth, 1922. Internet Archive, from a copy in Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 1 March 2025.

Wagner, Shandi Lynne. “Seeds of Subversion in Mary de Morgan’s ‘The Seeds of Love.’” Marvels & Tales 29. No. 2 (2015): 245–64. https://doi.org/10.13110/marvelstales.29.2.0245.

Created 1 March 2025