London is a world itself, and its records embrace a world history. (Garwood viii)

Introduction

The origins of London slums date back to the mid eighteenth century, when the population of London, or the “Great Wen,” as William Cobbett called it, began to grow at an unprecedented rate. In the last decade of the nineteenth century London's population expanded to four million, which spurred a high demand for cheap housing. London slums arose initially as a result of rapid population growth and industrialisation. They became notorious for overcrowding, unsanitary and squalid living conditions. Most well-off Victorians were ignorant or pretended to be ignorant of the subhuman slum life, and many, who heard about it, believed that the slums were the outcome of laziness, sin and vice of the lower classes. However, a number of socially conscious writers, social investigators, moral reformers, preachers and journalists, who sought solution to this urban malady in the second half of the nineteenth century, argued convincingly that the growth of slums was caused by poverty, unemployment, social exclusion and homelessness.

The Slums of East London

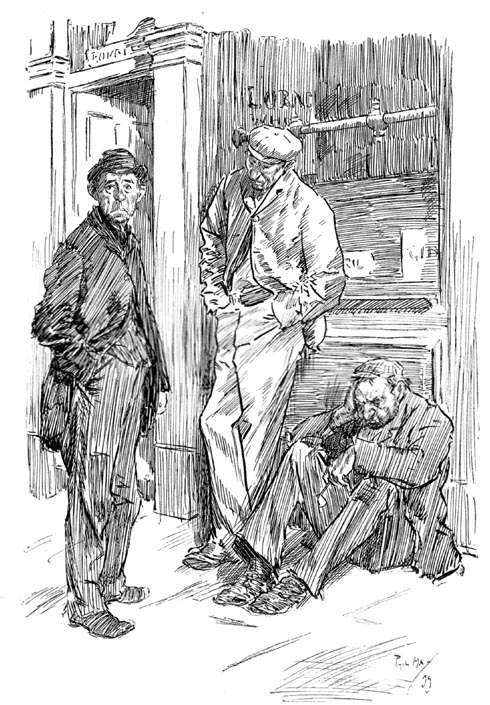

Two of Phil May's depictions of life in the East End: East End Loafers and A Street-Row in the East End.

The most notorious slum areas were situated in East London, which was often called "darkest London," a terra incognita for respectable citizens. However, slums also existed in other parts of London, e.g. St. Giles and Clerkenwell in central London, the Devil's Acre near Westminster Abbey, Jacob's Island in Bermondsey, on the south bank of the Thames River, the Mint in Southwark, and Pottery Lane in Notting Hill.

In the last decades of the Victorian era East London was inhabited predominantly by the working classes, which consisted of native English population, Irish immigrants, many of whom lived in extreme poverty, and immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe, mostly poor Russian, Polish and German Jews, who found shelter in great numbers in Whitechapel and the adjoining areas of St. George’s-in-the-East and Mile End.

Whitechapel

Two views of Whitechapel by Joseph Pennell: An East End Factory and Whitechapel Shops.

Whitechapel was the hub of the Victorian East End. By the end of the seventeenth century it was a relatively prosperous district. However, some of its areas began to deteriorate in the mid eighteenth century, and in the second half of the nineteenth century they became overcrowded and crime infested.

Whitechapel from the 1849 Illustrated London News.

Many poor families lived crammed in single-room accommodations without sanitation and proper ventilation. There were also over 200 common lodging houses which provided shelter for some 8000 homeless and destitute people per night. Margaret Harkness, a social researcher and writer, rented a room in Whitechapel in order to make direct observations of degraded slum life. She described the South Grove workhouse in her slum novel, In Darkest London:

The Whitechapel Union is a model workhouse; that is to say, it is the Poor Law incarnate in stone and brick. The men are not allowed to smoke in it, not even when they are in their dotage; the young women never taste tea, and the old ones may not indulge in a cup during the long afternoons, only at half-past six o'clock morning and night, when they receive a small hunch of bread with butter scraped over the surface, and a mug of that beverage which is so dear to their hearts as well as their stomachs. The young people never go out, never see a visitor, and the old ones only get one holiday in the month. Then the aged paupers may be seen skipping like lambkins outside the doors of the Bastile, while they jabber to their friends and relations. A little gruel morning and night, meat twice a week, that is the food of the grown-up people, seasoned with hard work and prison discipline. Doubtless this Bastile offers no premium to idle and improvident habits; but what shall we say of the woman, or man, maimed by misfortune, who must come there or die in the street? Why should old people be punished for their existence? [143]

Whitechapel was the venue of murders committed in the late 1880s on several women by the anonymous serial killer, called Jack the Ripper, who probably lived in the environs of Flower and Dean Street. The national press, which reported in great detail the Whitechapel murders, also revealed to the reading public the appalling deprivation and dire poverty of the East London slum dwellers. As a result, the London County Council tried to get rid of the worst slums by introducing several slum clearance programmes, but by the end of the nineteenth century few housing schemes for the poor were implemented. Jack London, who explored the living conditions of the poor in Whitechapel for six weeks in 1902, was astounded by the misery and overcrowding of the Whitechapel slums. He wrote a book about its miserable inhabitants and gave it the title The People of the Abyss.

Spitalfields

Spitalfields, which received its name from St. Mary's Spittel (hospital) for lepers, had been once inhabited by prosperous French Huguenot silk weavers, but in the early 19th century their descendants were reduced to a deplorable condition due to the competition of the Manchester textile factories and the area began to deteriorate into crime-infested slums. The spacious and handsome Huguenot houses were divided up into tiny dwellings which were rented by poor families of labourers, who sought employment in the nearby docks.

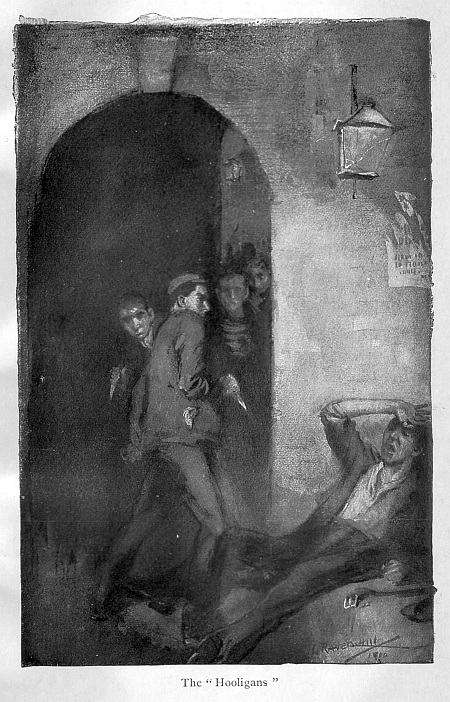

Three of Leonard Raven-Hill's depictions of life in the East End: A Corner in Petticoat Lane, The Hooligans, and A 'Schnorrer' (Beggar) of the Ghetto".

In the second half of the nineteenth century Spitalfields became home for Dutch and German Jews, and later for masses of poor Polish and Russian Jewish immigrants. Brick Lane, which passes through Spitalfields, was inhabited in the 1880s mostly by Orthodox Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. By the early 1890s a number of shuls (synagogues) and chevrots (small places of worship) had been opened in Spitalfields and the neighbouring areas. The Jews' Temporary Shelter was created in 1886 at Leman Street for new immigrants arriving in London from Eastern Europe.

Many philanthropic institutions were active in Spitalfields in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1860, Fr. Daniel Gilbert and the Sisters of Mercy opened a night refuge for destitute women and children in Providence Row. The American banker and philanthropist, George Peabody, created a foundation, which built the first improved dwellings for the “artisans and labouring poor of London” in Commercial Street in 1864. However, all these ventures were inadequate for the improvement of the living conditions of the poor. Arthur Morrison described the Brick Lane slums and its environs in The Palace Journal as places of darkness where “human vermin” lived:

Black and noisome, the road sticky with slime, and palsied houses, rotten from chimney to cellar, leaning together, apparently by the mere coherence of their ingrained corruption. Dark, silent, uneasy shadows passing and crossing – human vermin in this reeking sink, like goblin exhalations from all that is noxious around. Women with sunken, black-rimmed eyes, whose pallid faces appear and vanish by the light of an occasional gas lamp, and look so like ill-covered skulls that we start at their stare. [1023]

Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green was a place of small-scale manufacturing and shabby working-class housing. The local major employer was Allen & Hanbury's, one of the biggest factories in the East End, which produced pharmaceutical and medical goods. In the last three decades of the nineteenth century, it became an area of extreme poverty and overcrowded slums. In 1884, Keble College, Oxford University, established Oxford House Settlement in Bethnal Green as part of its philanthropic activity, which consisted in providing religious, social and educational work as well as healthy recreation among the poor of East London. The Settlement housed a boy's club, gym and library. Working-class inhabitants could listen to lectures, Bible readings and concerts. The residents of Oxford House were socially-conscious members of the upper classes who wanted to get acquainted with the sordid living conditions of the poor and, simultaneously, establish better cross-class relationships based on Christian brotherhood and benevolence.

The Old Nichol

The Old Nichol, situated between High Street, Shoreditch, and Bethnal Green, was regarded as the worst slum of the East End. It consisted of 20 narrow streets containing 730 dilapidated terraced houses which were inhabited by some 6,000 people. The London County Council (LCC) decided to clear the Old Nichol slums in the 1890s, and the first council housing development in Britain, called the Boundary Estate, was built in its place shortly before 1900. The deplorable conditions of the Old Nichol were immortalised by Arthur Morrison in his slum novel, The Child of the Jago.

Slumming

In the late Victorian era London's East End became a popular destination for slumming, a new phenomenon which emerged in the 1880s on an unprecedented scale. For some slumming was a peculiar form of tourism motivated by curiosity, excitement and thrill, others were motivated by moral, religious and altruistic reasons. The economic, social and cultural deprivation of slum dwellers attracted in the second half of the nineteenth century the attention of various groups of the middle- and upper-classes, which included philanthropists, religious missionaries, charity workers, social investigators, writers, and also rich people seeking disrespectable amusements. As early as in 1884, The New York Times published an article about slumming which spread from London to New York.

Slumming commenced in London […] with a curiosity to see the sights, and when it became fashionable to go 'slumming' ladies and gentlemen were induced to don common clothes and go out in the highways and byways to see people of whom they had heard, but of whom they were as ignorant as if they were inhabitants of a strange country. [September 14, 1884 ]

In the 1880s and 1890s a great number of middle- and upper-class women and men were involved in charity and social work, particularly in the East End slums. The national press covered widely shocking and sensational news from the slums. Anxiety and curiosity about slums could be heard in many public debates to that extent that, as Seth Koven writes:

By the 1890s, London guidebooks such as the Baedeker’s not only directed visitors to shops, monuments, and churches but also mapped excursions to world renowned philanthropic institutions located in notorious slum districts such as Whitechapel and Shoreditch. [1]

In fact, for a considerable number of Victorian gentlemen and ladies slumming was a form of illicit urban tourism. They visited the most deprived streets of the East End in pursuit of the 'guilty pleasures' associated with the immoral slum dwellers. Upper-class slummers sometimes spent in disguise a night or more in poor boarding houses seeking to experience taboo intimacies with the members of the lower classes. Their cross-class sexual fellowships contributed to diminishing class barriers and reshaping gender relations at the turn of the nineteenth century.

However, slumming was not only limited to odd amusement. In the last two decades of the Victorian era a rising number of missionaries, social relief workers and investigators, politicians, journalists and fiction writers as well as middle-class ‘do-gooders’ and philanthropists made frequent visits to the East End slums to see how the poor lived. A number of gentlemen and lady slummers decided to take up temporary residence in the East End in order to collect data on the nature and extent of poverty and deprivation. Some slummers were disguised in underclass drags in order to transgress class boundaries and mix freely with the poverty stricken inhabitants of the slums. Written or oral accounts of their first-hand observations arose public conscience and motivation to provide slum welfare programmes, and prompted political demands for slum reform.

The last two decades of the nineteenth century witnessed the upsurge of public inquiry into the causes and extent of poverty in Britain. Some of the most outstanding late Victorian slummers were Princess Alice of Hesse, the third child of Queen Victoria; Lord Salisbury, and his sons, William and Hugh, who resided temporarily in Oxford House, Bethnal Green; William Gladstone, and his daughter Helen, who lived in the south London slums as head of the Women's University Settlement. (Koven 10) Even Queen Victoria visited the East End to open the People’s Palace in Mile End Road in 1887.

Benevolent middle- and upper-class women went to slums for a variety of purposes. They volunteered in parish charities, worked as nurses and teachers and some of them conducted sociological studies. Such women as Annie Besant, Lady Constance Battersea, Helen Bosanquet, Clara Collet, Emma Cons, Octavia Hill, Margaret Harkness, Beatrice Potter (Webb), and Ella Pycroft explored some of London’s most notorious rookeries, and their eye-witness reports gradually changed the public opinion about the causes of poverty and squalor. By the turn of the nineteenth century thousands of men and women were involved in social work and philanthropy in London slums.

Slum Exploration Literature

In the second half of the nineteenth century, London slums attracted the attention of journalists and social researchers, who described them as areas of extreme poverty, degradation, crime and violence, and called for an immediate public action to improve the living and sanitary conditions of the working classes. “Slums ceased to be regarded as a disease in themselves and gradually came to be viewed as a symptom of a much larger social ill.” (Wohl 223) A number of contemporary accounts about subhuman life in the slums aroused public concern. Some of them helped prepare the subsequent slum reform and clearance legislations.

Out of a great number of publications that dealt with London slums, mention should be made of Hector Gavin's Sanitary Ramblings: Being Sketches and Illustrations of Bethnal Green (1848), Henry Mayhew's London Labour and London Poor (1851), John Garwood's The Million-People City (1853), John Hollinghead's Ragged London (1861), J. Ewing Ritchie's The Night Side of London (1861), James Greenwood's The Seven Curses of London (1869) and The Wilds of London (1874), Adolphe Smith's Street Life in London (1877), Andrew Mearns' The Bitter Cry of Outcast London (1883), George Sims' How the Poor Live (1883), Henry King's Savage London (1888), Walter Besant's East London (1899), Charles Booth's monumental report, Life and Labour of the People in London (17 volumes, 1889–1903), and B. S. Rowntree’s Poverty: A Study of Town Life (1901). All these reports are valuable social documents which provide background information about the deplorable slum conditions in late Victorian London. They are available in an electronic form on the Internet.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that late Victorian slums were the consequence of the rapid industrialisation and urbanisation of the country, which led to a more dramatic spatial separation between the rich and the poor, known as the two-nation divide, with incomparably different lifestyles and living standards. Slumming, which became a way of getting immersed in slum culture, contributed to the development of public awareness that slum conditions were not providential and deviant, but rather afflicted by the economy and circumstances, and could be improved by an adequate economic, social and cultural policy.

Related Material

- After Crimea: Florence Nightingale and Slum Clearance

- The Slum of All Fears: Dickens's Concern with Urban Poverty and Sanitation

- A Brief History of London

- Filth and Class

- Clara Collet and Jack the Ripper

- Peabody Square in Blackfriars Road (model dwellings)

References and Further Reading

Ackroyd, Peter. London: The Biography. London: Vintage: London, 2001.

Chadwick, Edwin. Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. 1842. Ed. & Intro. M.W. Flinn. Edinburgh: University Press, 1965.

Chesney, Kellow. The Anti-society: An Account of the Victorian Underworld. Boston: Gambit, 1970.

Cobbett, William. Rural Rides. London: Published by William Cobbett, 1830.

Dyos, H. J. and D. A. Reeder. “Slums and Suburbs,” The Victorian City, ed. H. J. Dyos, and M. Wolff, 1:359-86. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973. ___. “The Slums of Victorian London, ” Victorian Studies, 11, 1 (1967) 5-40.

Koven, Seth. Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London. Princeton University Press, 2004.

Gordon, Michael R. Alias Jack the Ripper: Beyond the Usual Whitechapel Suspects. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2001.

Garwood, John. The Million-Peopled City; or, One Half of the People of London Made Known to the Other Half.. London: Wertheim and Macintosh, 1853.

Haggard, Robert F. The Persistence of Victorian Liberalism: The Politics of Social Reform in Britain, 1870-1900. Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 2001.

Harkness, Margaret. In Darkest London. Cambridge: Black Apollo Press, 2003.

Kellow Chesney, The Victorian Underworld. Harmonsworth: Penguin, 1970.

Lees, L. H. Exiles of Erin: Irish Migrants in Victorian London. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979.

London, Jack. The People of the Abyss in: London: Novels and Social Writings. New York: The Library of America, 1982, also available from Project Gutenberg.

Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the London Poor. 4 vols. 1861-2. Intro. John D. Rosenberg. New York: Dover Publications, 1968.

Morrison, Arthur. “Whitechapel,” The Palace Journal, April 24, 1889; also available at: http://www.library.qmul.ac.uk/sites.

Olsen, Donald J. The Growth of Victorian London. New York: Holmes & Meier 1976.

Porter, Roy. London: A Social History. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Ross, Ellen, ed. Slum Travelers: Ladies and London Poverty, 1860-1920. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007.

Ross, Ellen. “Slum Journeys: Ladies and London Poverty 1860-1940,” in: Alan Mayne and Tim Murray, eds. The Archaeology of Urban Landscapes: Explorations in Slumland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Scotland, Nigel. Squires in the Slums: Settlements and Missions in Late Victorian Britain. London. I.B. Tauris & Co., 2007.

Stedman Jones, G. Outcast London: A Study in the Relationship Between Classes in Victorian Society. Oxford: Peregrine Penguin Edition, 1984. “Slumming In This Town. A Fashionable London Mania Reaches New York. Slumming Parties To Be The Rage This Winter, ” The New York Times, September 14, 1884.

Wohl, Anthony S. The Eternal Slum: Housing and Social Policy in Victorian London. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2009.

___. Endangered Lives: Public Health in Victorian Britain. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard UP, 1983.

Yellling, J. A. Slums and Slum Clearance in Victorian London. London: Allen & Unwin, 1986.

Last modified 3 October 2013