Apart from the first picture of the book cover, the illustrations here have been added from our own website rather than from the book itself. Unless otherwise specified, they are all reproductions of photographs taken by Lewis Carroll, who was, of course, a pioneering photographer. They come from his nephew's biography of him (see "Sources" at the end) or, by kind permission, from the National Portrait Gallery, London. Please click on them for larger pictures, and generally for more information. Headings and links have also been added. — Jacqueline Banerjee.

Edward Wakeling's earliest article on Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) mentioned in the bibliography of this book was published in 1977. Virtually a page of the three and a half pages of the bibliography is taken up by 18 entries in his name including the ten volumes of Carroll's Diaries which he edited and which came out between 1993 and 2007. There are a couple of other entries for books which he wrote along with a co-author. He is a former chairman of the Lewis Carroll Society. The fly leaf paragraph on Wakeling makes no mention of anything he has done which is unconnected to Carroll.

This almost lifelong devotion to a single person – author, photographer, mathematician, clergyman, college administrator – tells the reader what to expect for ill as well as for good. For a reader with a passing interest in Carroll there must be better places to start. The book makes no claim to be a conventional biography and makes a firm claim to leave any judgment about aspects of Carroll's life to the reader. It seeks to shed light on Carroll by brief accounts of a selection from the wide range of people in his social circle. Wakeling also seizes the opportunity to correct errors of fact or judgment in books on Carroll by others whether on relatively detailed points or on central issues.

Lewis Carroll's Character

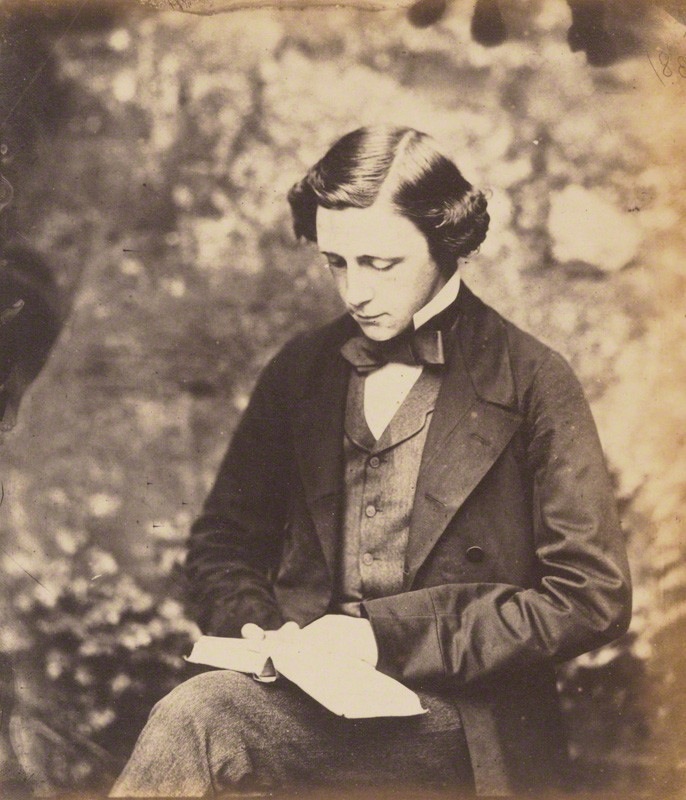

A studious young Lewis Carroll, self-portrait of c.1857. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

From Carroll's contact with those on whom Wakeling has chosen to concentrate he builds up a picture of Carroll which he summarises on the penultimate page:

a kind and generous person, especially to his extended family, a devoutly religious man, someone with high intelligence, a very creative and imaginative mind that led to works of international fame, an obsessive and ordered personality with an excessively pedantic streak, a man with strong beliefs and standards upholding the Victorian values of service and duty, and a fascinating and complex personality that has intrigued and confused people for many decades. [363]

That is a fair and truthful summary of an interesting Victorian but it doesn't tell the whole story that emerges from the book. Wakeling's intention to leave judgment to his readers is not achieved. His sympathy and admiration for Carroll is apparent on every page and was bound to be so. Others may be confused by Carroll's personality but Wakeling opts vigorously for a generous interpretation of every episode or attitude that might leave room for doubt.

Carroll was ordained deacon in the Church of England as was required in order to earn a living in Christ Church, Oxford in the 1850s. He successfully obtained permission to remain as a deacon and was never ordained as a priest as almost everyone in his position would have been. He successfully obtained permission to remain as a deacon and was never ordained asa priest as almost everyone in his position would have been. This closed off any chance of a college living, the normal route to a higher standard of living and marriage for young Oxford academics. Many of his contemporaries who remained in the university and, as time went on were free to marry because practice changed, would have given more of their time and energy to scholarship than did Carroll. His interests shifted gradually and he retired early from teaching. Until he did there is nothing to suggest that he was inattentive to his duties but the best of him went into writing books for children and into photography even when he still held a full-time university post.

Lewis Carroll and Children

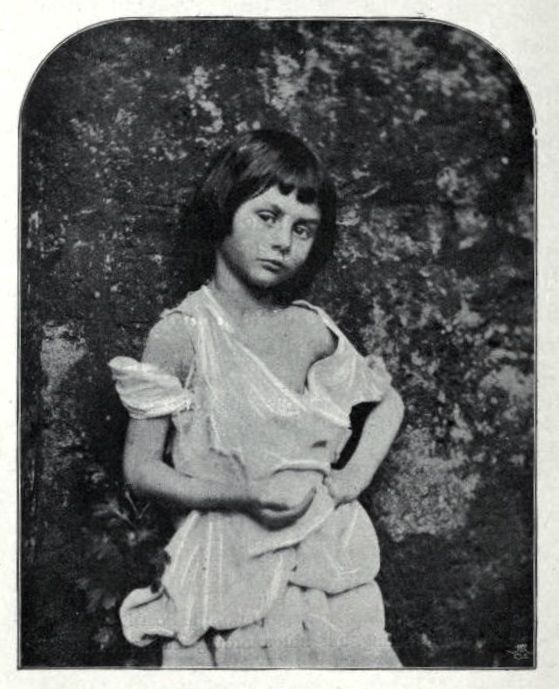

Left to right: (a) "Alice Liddell [the original of Alice] as Beggar-Child," 1860. Source: Collingwood, facing p. 81. (b) Edith May Liddell, Alice's younger sister. © National Portrait Gallery, London. (c) Alice Liddell in 1870. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Carroll's friendships with children, his admiration for those whom he considered beautiful, whether girls (the majority) or boys, his photographs of nude children and his drawing of nude children from life are, of course, well-trodden ground in any book about Carroll. It is possible to be persuaded – as Wakeling is beyond doubt – that this side of Carroll's life was wholly innocent and showed no more about him than that he was a man of his time but still to be left uneasy. His correspondence with children and his enthusiasm for their company leaves room for doubt about how satisfactory he found his social interaction with adults. Few, if any, of the adults that Wakeling chooses to cover in the book could be said to have been a close friend of Carroll over several decades. There was certainly a side to Carroll which only found full expression in his relationships with children but Wakeling convincingly acquits him of the charge of losing interest in children as they grew up.

Lewis Carroll and Women

Ellen Terry. Source: Collingwood 182.

Carroll got on well with women. He supported higher education for women and, when many would have disagreed with him, believed that they should take degrees. Some of his attitudes strike the 21st century reader as surprising. He was friendly with Ellen Terry during both her marriages. Between her marriages she lived with someone to whom she wasn't married and Carroll shunned her. He consulted many of his women friends about a project he conceived to produce an edition of Shakespeare suitable for girls. The project was never realised. He suggested to his friend Thomas Gibson Bowles, the editor of Vanity Fair, that he might produce a regular list of plays and other entertainments to which "ladies might safely be taken". In these and other matters Wakeling defends Carroll as simply reflecting Victorian values but they may tell us something about Carroll as well as something about the age in which he lived.

One drawback of the book for someone only generally interested in learning something about Carroll is Wakeling's own deep interest in every detail and his determination to share it with his readers. Few people are interested in Carroll the mathematician and most will therefore find more in the book about that than they care to read. Because of his role as curator of the Christ Church Common Room, Carroll was heavily involved in the extension of the wine cellar; the detailed account of the building will probably hold the attention of a minority of readers. The attention to detail is not restricted to Carroll. For example, the pages on Emily Gertrude Thomson, a decorative illustrator, begin with a paragraph on her family which includes a list of her six siblings, two of whose names are not known.

A consequence of the way the book is put together is that some sections give the impression that they were prepared for a different purpose and have been slotted in without quite enough attention to continuity. The structure also means that some irritating repetition is inescapable.

Lewis Carroll and his Celebrated Acquaintances

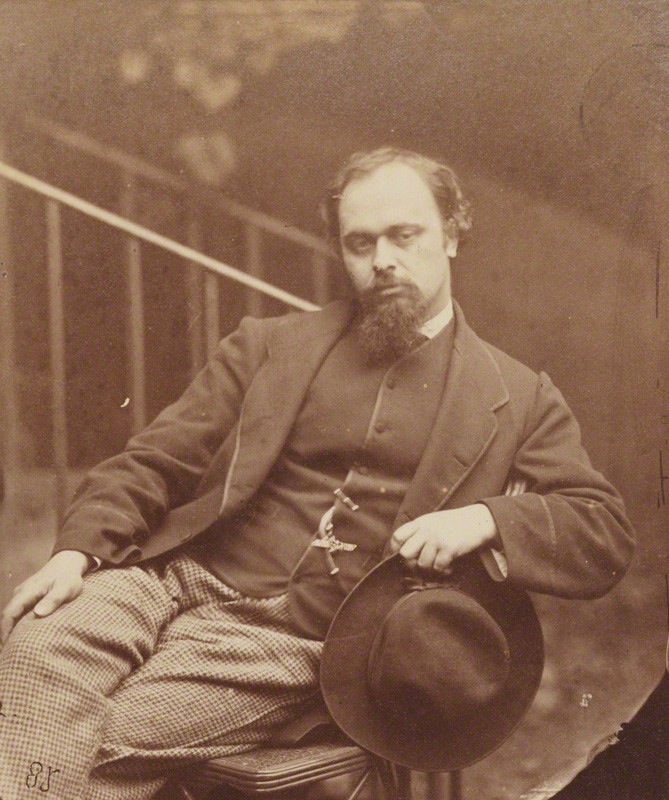

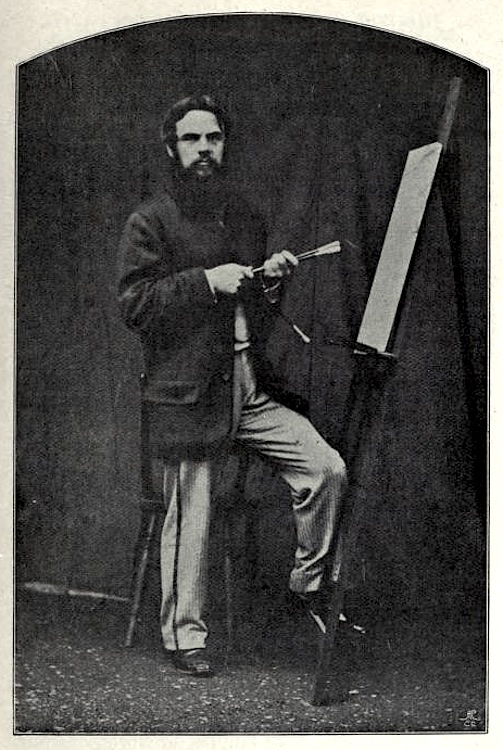

Left to right: (a) Dante Gabriel Rossetti. © National Portrait Gallery, London. (b) William Holman Hunt. Source: Collingwood, facing p. 102. (c) Alfred Tennyson. Source: Collingwood, facing p. 71. (c) The Late Duke of Albany (Prince Leopold). Source: Collingwood, facing p. 286.

Notwithstanding these comments the book is full of interest about Victorian England generally. Carroll's life was scarcely typical but the book offers many insights into nineteenth-century Oxford and particularly the university. Wakeling writes about people that Carroll knew slightly and only briefly as well as those who featured in his life over a number of years. His life in a prominent Oxford college and his fame as a writer combined to bring him into contact with a wide range of interesting people. Amongst those covered in the book are Alexander Macmillan, the publisher, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Millais, Holman Hunt, Arthur Sullivan, Tennyson, Ellen Terry (as mentioned above), and Prince Leopold, Queen Victoria's youngest child.

Lewis Carroll and His Illustrators

Two more illustrations from Collingwood's biography of his uncle. Left: John Tenniel (from a photograph of Bassano), facing p. 129. Right: "Medley of Tenniel's Illustrations in 'Alice' (From an etching by Miss Whitehead; used in a theatrical avertisement)," facing p. 264.

The chapter on illustrators is particularly interesting both because of the individuals, pre-eminently Tenniel, and because it sheds light on the relationship between the author of an illustrated book and the illustrator. Carroll may have been unusually demanding, not least as an amateur artist himself, but tension seems to be intrinsic to the nature of this particular relationship.

The book is happily and effectively illustrated by Carroll's own photographs. More than most books it reflects a life of single-minded attention to its central subject. It is full of illuminating material and as informative on Carroll's circle as on the man himself.

Related Material

- Another review of Edward Wakeling's book

- A Tenniel Gallery (1): Illustrations for Alice in Wonderland

Sources

(Book under review) Wakeling, Edward. Lewis Carroll: The Man and His Circle. London: I. B. Tauris, 2015. Hardcover. £35.00. xvi + 400pp. ISBN: 978-1780768205.

(Illustration source) Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson. The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll (Rev. C. L. Dodgson). London: Unwin, 1898. Internet Archive. From the Fisher Walsh collection, University of Toronto. Web. 12 May 2015.

Created 12 May 2015