This review is reproduced here by kind permission of Professor Bury and the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where the review was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee.

as there still any room for one more biography of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll? That is probably the question Edward Wakeling asked himself before he started writing his book. After Morton N. Cohen and so many others, what kind of narrative could still be written? Having pondered the problem, Edward Wakeling decided to "deconstruct" the biography he may have had in mind, and to write it according to a plan which would necessarily appeal to academics rather than to a wider audience. Dodgson — one suspects the pseudonym "Lewis Carroll" was only used by I.B. Tauris in order to make the title more explicit — is presented as (almost) an ordinary man, who led an eventful life, had a number of interests in life and met a number of people. More than a biography, this book therefore takes the aspect of a non-alphabetical "Companion to Lewis Carroll," in which a rough sort of chronology is followed in the first two chapters only, logically enough since the volume opens with Dodgson's family and teachers.

as there still any room for one more biography of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll? That is probably the question Edward Wakeling asked himself before he started writing his book. After Morton N. Cohen and so many others, what kind of narrative could still be written? Having pondered the problem, Edward Wakeling decided to "deconstruct" the biography he may have had in mind, and to write it according to a plan which would necessarily appeal to academics rather than to a wider audience. Dodgson — one suspects the pseudonym "Lewis Carroll" was only used by I.B. Tauris in order to make the title more explicit — is presented as (almost) an ordinary man, who led an eventful life, had a number of interests in life and met a number of people. More than a biography, this book therefore takes the aspect of a non-alphabetical "Companion to Lewis Carroll," in which a rough sort of chronology is followed in the first two chapters only, logically enough since the volume opens with Dodgson's family and teachers.

Edward Wakeling has been a Dodgson fan for several decades, he succeeded Anne Clark Amor as chairman of the Lewis Carroll Society, and over the years, he has devoted several books to his main interest. He edited Dodgson's diaries and devoted a fascinating volume to Carroll's relations with his illustrators (Cornell UP, 2003). Nobody is probably more knowledgeable about the author of Alice in Wonderland nowadays, and this new book is literally packed with fascinating nuggets of information about all sorts of topics. Quite clearly, Wakeling's intention was to take arms — once again, but it is a never-ending fight – against those who depict Lewis Carroll as a closet paedophile, as a pathologically asocial being who could only breathe in the company of very young, preferably female, children. This biased and unfounded stereotype has been consistently exposed as pure fantasy, but prejudices die hard and have to be killed several times before they vanish. Of course, the destruction of some of Dodgson's diaries by his sisters means that "biographers are bereft of key primary source material. But to indulge in unfounded speculation is not the way forward" (267). Let the reader be warned: in this book, he or she will find plenty of substantiated assertions but hardly any hypotheses.

The table of contents itself is indicative of this decision to write about a "normal" man, who had "normal" interests and led a busy life. Children do not occupy centre space, and they are only discussed in the ninth chapter (out of twelve): "Friends and children" opens with an adult, Robinson Duckworth, who was closely associated with the creation of the Alice story, since he took part in the fateful excursion on the Isis river, on July 4th 1862. Children therefore come long after other "categories" like publishers, mathematicians, photographers, artists and actors. This decision is easily understood, but the choice of an achronological plan also means, for instance, that the history of the conception, writing, illustration and publication of the Alice books is necessarily split between several different chapters. The initial river trip is discussed on pages 232-235; Alice Liddell's own version is quoted on page 246. As there is no specific chapter about Dodgson's writer friends, there are no special pages devoted to George Macdonald's reaction to the first draft of the story, except a brief mention extracted from the diary, "Heard from Mrs MacDonald about 'Alice's Adventures Under Ground,' which I had lent them to read, and which they wish me to publish'" (71). Dodgson's exchange of letters with Tom Taylor about the possibility of Tenniel illustrating the book, in December 1863, is reproduced on pages 219-220. The letters to Tenniel appear on pages 73-79; dealings with Macmillan on page 54. The choice of a title for the published version was also discussed with Taylor (222). Obviously, as mentioned above, this is not the kind of book one will turn to in order to find a consecutive narrative of events. From that point of view, Lewis Carroll: The Man and his Circle may remind the reader of Kali Israel's Names and Stories: Emilia Dilke and Victorian Culture (OUP, 1999), which claimed to be "not a biography of Emilia Dilke but an examination of the stories and texts that constitute her," the lady being used "as a site for analysis of nineteenth-century Britain."

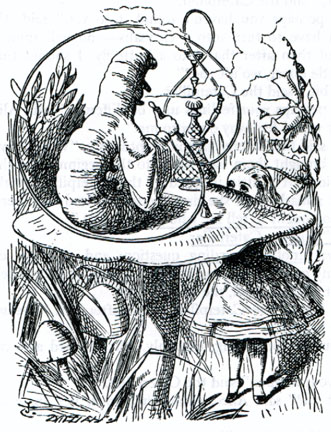

Three of Tenniel's famous illustrations for Alice, from wood engravings by Dalziel. Left to right: (a) Alice Catches Sight of the White Rabbit. (b) Alice and the Dodo. (c) Alice Meets the Caterpillar. [Click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information.]

Dismissing the "suggestions that he was shy and reclusive" (38), Edward Wakeling quotes from memoirs and letters to show that "Dodgson was not an easy man to work with" (53), constantly alternating between moments of hard work and bouts of indolence (30). Dodgson's father is granted more space than usual, and Wakeling quotes a wonderfully nonsensical example of his letter-writing, in which one can easily find adumbrated Lewis Carroll's own style (6). Besides, the biographical information goes much further than the mere evocation of Dodgson's circle. When discussing the writer's relations with his illustrators, and with John Tenniel in particular, Edward Wakeling includes a highly informative development about the art of woodblock engraving (70-71), which is very welcome as hardly anyone among devoted readers of Alice masters that kind of technological knowledge. Obviously, the more technical aspects of photography in its early decades also deserved a few paragraphs (156-158).

One of the pictures that Dodgson "saw and commented on": William Dyce's Titian Preparing to Make His First Essay in Colouring. [Click on the image to enlarge it, and for more information.]

The book even includes pages about Lewis Carroll's artistic tastes, beyond the evocation of the artists he met and became friends with: Wakeling details "four examples of paintings and drawings that Dodgson saw and commented on" in order to "give some idea of what appealed to him" (184), and mentions some of the (mainly Italian) operas which he attended on his frequent trips to London (196-197).

As usual, it seems extremely hard for English-speaking publishers to get foreign names right. Opera singer Giulia Grisi thus becomes "Guilia" (196), the comic opera La figlia del reggimento turns into di Reggimento (197), and Offenbach is credited with a "light comedy" strangely entitled La Vie (197), which is probably La Vie parisienne, curiously deprived of its indispensable epithet.

Of course, as the author himself admits in his epilogue, this is only a "very selective" survey of "some key people who were part of Dodgson's social circle" (363). Which is all very fine, were it not for the slightly hagiographic character of the enterprise, the aim of which seems to prove that Dodgson was possessed of all sorts of human (and super-human) qualities. Edward Wakeling claims to provide us with no more than facts. "The interpretation is left to the reader" (363), who should bear in mind that the Victorians were not exactly like twentieth- or even twenty-first-century people. The last words of the book are therefore: "He was a man of his time" (364). But neither was he a Hottentot living in the Middle Ages, and the temptation to interpret the man through the wild fantasies expressed, if not in his private papers, at least in his published work, is indeed a hard one to resist.

Related Material

- Another review of Edward Wakeling's book

- A Tenniel Gallery (1): Illustrations for Alice in Wonderland

Source

(Book under review) Wakeling, Edward. Lewis Carroll: The Man and His Circle. London: I. B. Tauris, 2015. Hardcover. £35.00. xvi + 400pp. ISBN: 978-1780768205.

Created 29 June 2015; last modified 4 July 2015