|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Phiz's Dark Plates: A Radical Change to Book Illustration

Phiz may have possessed less technical expertise than either George Cruikshank and Robert Seymour for conveying texture and shadow in his illustrations, relying heavily on short strokes and cross-hatching, as well as on the roulette and the ruling machine. However, possibly in imitation of the dark plates of John Franklin in the 1841 serialisation of Old St. Paul's, Browne discovered a way of creating special lighting effects by using varnish for stopping-out. After an iniial period of experimentation, Phiz employed this radical, time-consuming technique extensively for tonal paintings in Charles Dickens's Bleak House (1851-53) with ruling machine and varnish, and William Harrison Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe (1851-58). However, he seems to have employed it more frequently in illustrating the novels of Anglo-Irish writer Charles Lever:

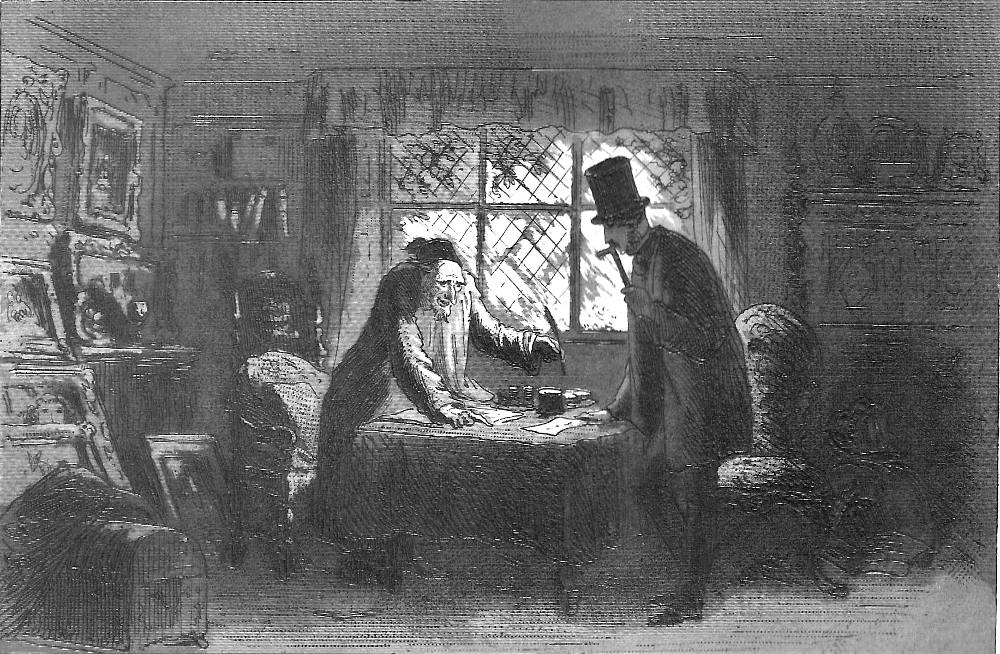

In his 'dark plates', innumerable layers of varnish are added during the biting in, so as to give an almost infinite gradation of tones to the one set of ruled lines that has been mechanically laid across the whole plate. He first develops this resource with any fullness in the plates for Lever's Roland Cashel [1849]. The frontispiece and The Game at Monte are magnificent paintings in tone, with a rich effect of darkness and evanescent glimmering. And it is in the darker scenes that his use of this resource is strongest. For though Browne had a lively sense of outline, and a natural instinct for design and the attractive distribution of tones, he had little sense of the power of tone to model the figure, and in those plates showing brightly lit scenes, he scarcely attempts any modelling. Instead, he picks out and highlights faces and other points of interest, and darkens other areas as best suits the design. [Harvey, p. 185]

Phiz produced fourteen of these dark plates in the series of forty-four illustrations for the July 1857-April 1859 serialisation of the Lever novel. In the first six monthly instalments (July-December 1857), Phiz has provided four dark plates (33% of the total), whereas in the twelve instalments for 1858 he has provided ten (42% of the total); however, in the final four instalments, of a total ten illustrations, including the frontispiece and title-page vignette, Phiz has provided just one dark plate, suggesting either that he found little material suitable for dark plates, or that he simply did not have the time to devote to the process, perhaps because the new Dickens commission was proving time-consuming.

A New Technique: Phiz's Dark Plates (1847-57)

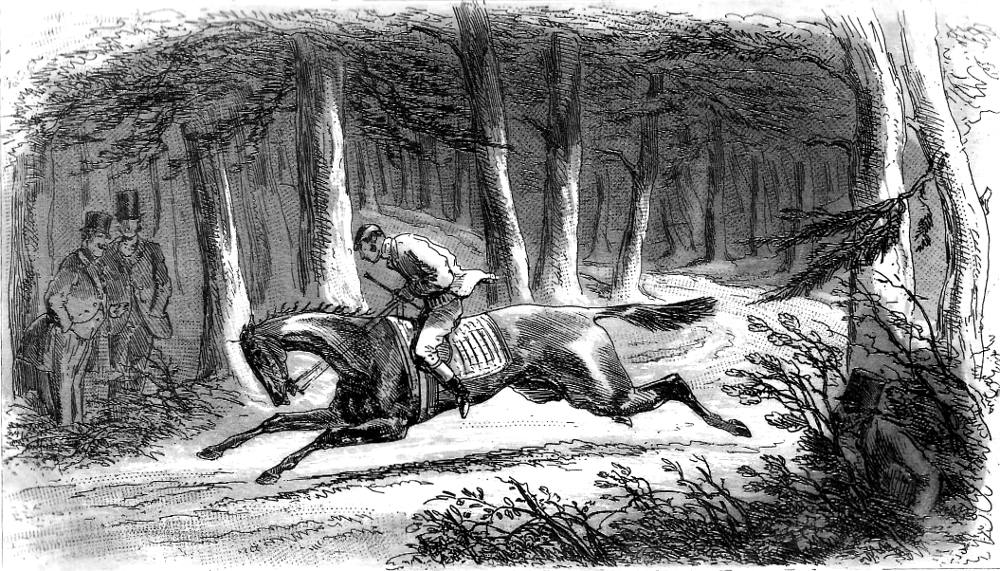

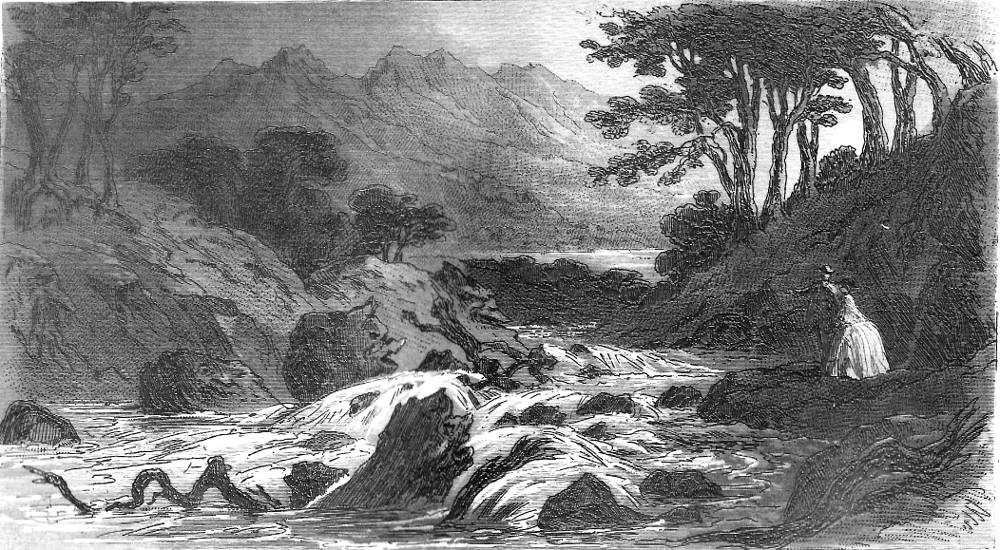

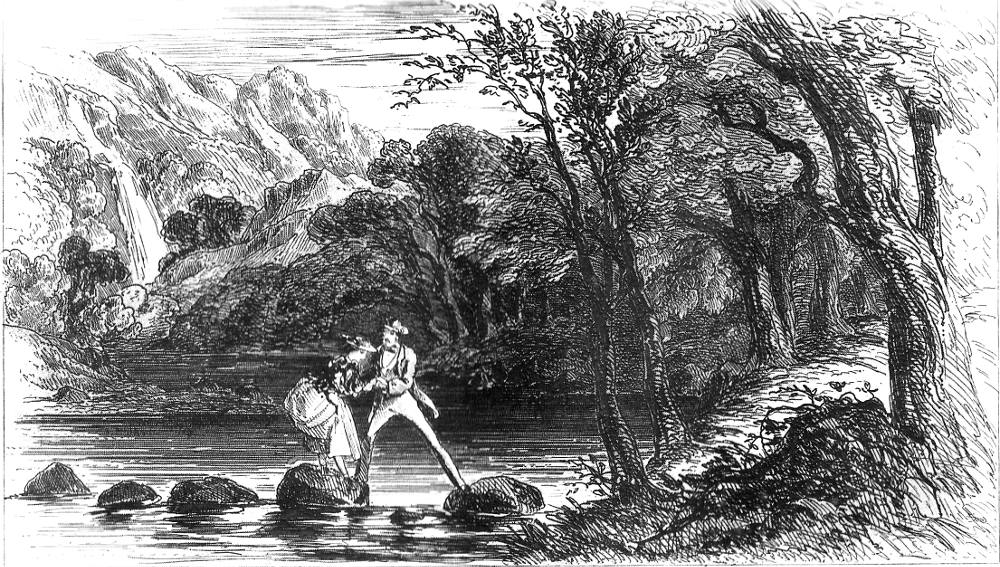

Beginning in 1847, Phiz had begun to experiment with creating dramatic effects through extreme chiaroscuro by etching 'dark plates', an effect he achieved by scoring the plate with closely set parallel lines after bolting out areas that were not to receive the extra ink. Steig argues that Phiz had learned the technique by studying John Franklin's dark plates for W. H. Ainsworth's Old Saint Paul's (1841). Such atmospheric illustrations as Phiz's interpretation of the squalid Tom-all-alone's in Chapter 46 of Bleak House (1853) use intense shades of grey to describe twilight, evening, night, and gloomy interiors, and invest them with suggestions of the moods ranging from the sinister, to the malignant, and the apprehensive. In the atmospheric and emotionally charged frontispiece for the Ainsworth novel which he produced in May 1858, the partially hidden moon and dark clouds intensify the suspenseful mood. But in the previous year, he had produced a number of equally atmospheric plates, including Going Home for the November 1857 number of Lever's Davenport Dunn, and Conway on escort duty for the December 1857 number.

Since the production of dark plates for Phiz proved far more time-consuming than work on conventional engravings, that he did so many for both Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe (December 1851-March 1852; December 1857 to June 1858) and Lever's Davenport Dunn (July 1857 to April 1859) is all the more remarkable when one considers the significant number of commissions that he undertook during he period that these novels were running as monthly serials:

Principal Novels Illustrated in 1857

- Ainsworth's The Spendthrift (January 1855-January 1857)

- Dickens's Little Dorrit (Dec., 1856-June 1857)

- Fielding's Amelia

- Fielding's Tom Jones

- Fielding's Joseph Andrews

- Smollett's Humphrey Clinker

- Smollett's Roderick Random

- Smollett's Peregrine Pickle

Principal Novels Illustrated in 1858

- Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe (December 1857-June 1858)

- Mayhew's Paved with Gold

- Thornbury's The Buccaneers

A New Form Emerges in Phiz's Second Phase, 1850-60

John Buchanan-Brown rightly commends such dark plates as an inspired development in Phiz's illustration, which, owing the increasingly pictorial and descriptive prose of writers such as Dickens and Lever, did not have to convey incident and character so much as atmosphere, including sinister darkness, chilly bleakness, and the illusion of intermingled sunlight and shadow:

Thus he tends to simplify his etching on the one hand, using a line unsupported by hatching, and on the other increasingly to use 'stopping-out' to achieve the effect of a pen-and-wash drawing, both these concurrently with a far higher proportion of his atmospheric 'dark' plates. perhaps because the novels themselves were moving away from the need for specific illustration [i. e., realisation of incidents], these dark plates are the best things which Browne produced during what may be termed his second phase, roughly between 1850 and 1860. [23]

When in November 1857, after an hiatus of five years, Hablôt Knight Browne returned to the commission for Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe with another publisher, Routledge, he had become enamoured of the so-called "dark plate," an atmospheric treatment upon which he had begun to rely in the monthly illustrations for Bleak House. Consequently, perhaps because he had time on his hands as well as the inclination to experiment with the technique, Phiz employed this engraving technique for a significant number of the illustrations in December 1857 through June 1858 instalments of the revived Ainsworth serial, including the frontispiece and title-page vignette. Of the twenty-four steel-engravings for Mervyn Clitheroe, none of the eight are dark plates in Book the First (December 1851 through March 1852), but twelve of the sixteen plates for the second and third books demonstrate Phiz's mastery of this engraving technique. Although he may have found less to inspire him in the regular steel engravings Lever's Davenport Dunn than in Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, he seems to have had more time on his hands earlier, in 1857-58, and was therefore inclined to expend the additional effort required for the dark plates in the Lever novel, which from the opening chapters features some highly atmospheric scenes that lend themselves to this technique. Whatever the cause for his interest in producing dark plates for Davenport Dunn, Phiz produced fourteen of these dark plates in the series of forty-four illustrations for the July 1857-April 1859 serialisation of the Lever novel. In the first six monthly instalments (July-December 1857), Phiz has provided four dark plates (33% of the total), whereas in the twelve instalments for 1858 he has provided ten (42% of the total); however, in the final four instalments, of a total ten illustrations, including the frontispiece and title-page vignette, Phiz has provided just one dark plate, suggesting either that he found little material suitable for dark plates, or that he simply did not have the time to devote to the process. Perhaps the stopping-out process was proving so time-consuming (for it must have involved considerable trial-and-error), that he used it sparingly in A Tale of Two Cities, which contains only one pure example, The Mail (June 1859).

The Normal Printing Process: Steel Plate Engravings and Dark Plates

The copper or steel-plate is placed above a charcoal fire, and warmed before the ink is rubbed into the hollowed lines by a woollen ball. When enough of ink is thus put into the lines, the surface of the plate is wiped with a rag, and cleaned and polished with the palm of the hand lightly touched with whiting. The paper is then laid on the plate, and the engraving is obtained by pressing the paper into he inked lines. — The London and Westminster Review (18380, 266; cited by Harvey, p. 190]

The artist printed a dark plate in a similar fashion as a conventional engraving, but the plate itself would hold more ink because key areas were either more intensely engraved (with cross-hatching and the roulette) or stopped out with varnish to convey a sense that the scene is transpiring at night or in a darkened room. The intense tonal illustration is thus able to convey a subtle range of moods that a conventional line drawing cannot: in the hands of an accomplished illustrator such as Phiz, the atmospheric dark plate may suggest mystery, melancholy, obscurity, or a combination of these.