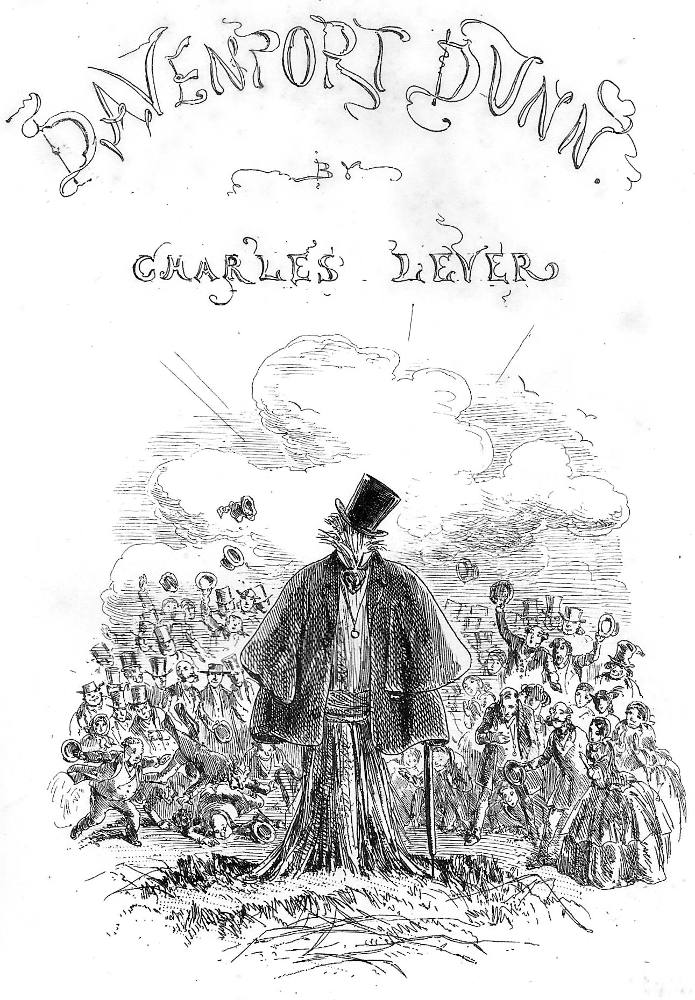

Engraved Title-Page

Phiz

Dalziel

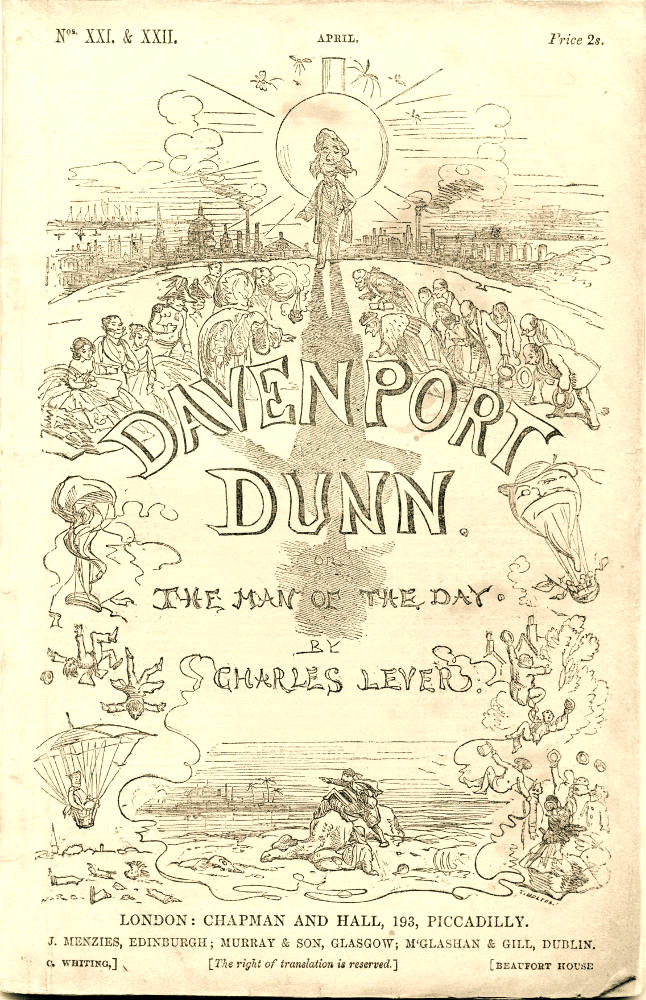

April 1859

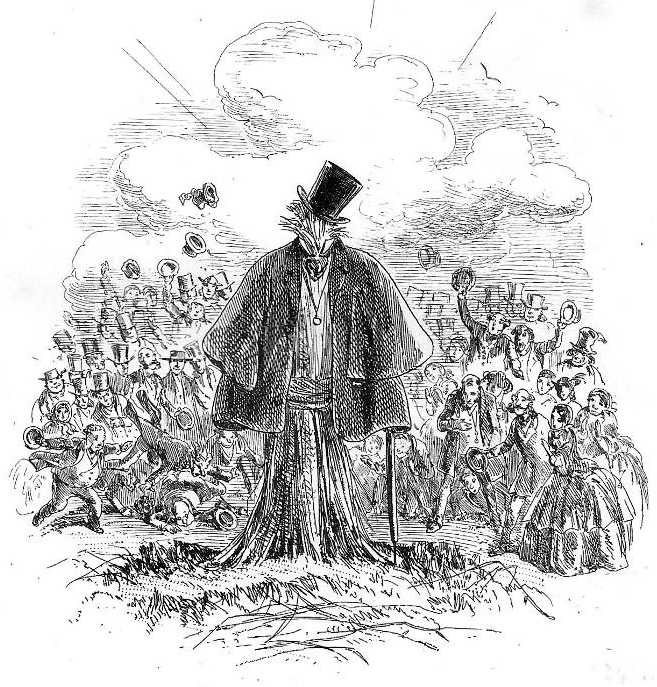

Steel-engraving

14.5 cm (5 ½ inches) high by 10 cm (3 ¾ inches) wide, vignetted

In the final (twenty-second) instalment for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day, title-page vignette and engraved title (1859 edition).

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image by Simon Cooke; colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliographical Information

In the 1859 (first edition) single-volume edition the enigmatic Title-page Vignette appeared as the second illustration, but in fact had already appeared in the final instalment, in April, illustrating Lever's winding up of the story with the trial of Grog Davis for Dunn's murder in Chapter LXXVIII, "The Trial." This same chapter appeared as Chapter XXXV in the second volume of the Chapman & Hall two-volume edition of 1872 (re-issued in 1901 by Little, Brown & Co., Boston). Although in the volume edition this vignette-title is the book's second illustration, originally it was the fourth of four illustrations in the April 1859 double-number (Parts XXI & XXII). This final number included Chapters LXXIV through LXXIX, and ran from page 641 to 695.

Commentary: A Symbolic Title-Page Vignette — Davenport Dunn as a Straw Man

Phiz faced the problem that, although serial readers would quickly apprehend the significance of the illustrator's depicting the eponymous character as a well-dressed scarecrow, purchasers of the April 1859 Chapman and Hall volume would be puzzling over its meaning for seventy-five chapters. However, Phiz must have realised that contemporary readers would make the connection between the fictional Dunn and the actual Irish confidence man John Sadleir (1813-1856), and that therefore the visual metaphor would serve as constant foreshadowing, reiterated every time that reader opened the volume from the front. Even as readers watch Dunn deal with reversals and advance his financial empire, the vignette prepares them for the inevitable collapse.

As George Robb explains in White-Collar Crime in Modern England (2002),

The nation was shocked . . .by the exposure of John Sadleir's frauds at the Tipperary Joint-Stock Bank. As director of the bank, Sadleir had embezzled some £200,000. Another £400,000 was lost when the bank suspended payment. Sadleir had come to London in 1846 as an agent for Irish railway schemes. Augmenting his directorship of the Tipperary Bank, Sadleir became chairman of the London and County Bank and the Royal Swedish Railway. Elected to Parliament he was a spokesman for business interests and was eventually appointed a Lord of the Treasury. As it later transpired, Sadleir had buit his vaunted financial reputation on a series of monstrous impostures. Besides his embezzlements from the Tipperary Bank, he issued fictitious shares in the Swedish Railway to the extend of £150,000. While a member of the Irish Encumbered Estates Commission Sadleir also forged title deeds to a number of properties. Rumours of his misfeasance had forced his resignation from the Treasury and the London and County Bank, and the crash of the Tipperary Bank in January of 1856 laid bare his crimes. Sadleir immediately committed suicide, inspiring Dickens to create the character of Mr. Merdle [in Little Dorrit].

On the very heels of Sadleir's demise, the Royal British Bank failed amid revelations that the bank manager, Hugh Cameron, and two directors, Humphrey Brown and Edward Esdaile, had wasted the bank’s resources in unsecured loans to themselves and their friends. [62]

Lever, perhaps with a tinge of national pride, could not bring himself to have his titular hero commit suicide in a public park as an easy way out of cheating the law once the authorities discovered his financial crimes and exposed his fraudulent investment schemes. Rather, the ruthless Christopher ('Grog') Davis, a gambler and sharper, kills Dunn in self-defence. In "The Train," Davis breaks into Dunn's private club-car and attempts to rob Dunn of documents that Davis mistakenly believes support Charles Conway's claim that by genealogical right he and not Annesley Beecher, Davis's son-in-law, should enjoy the title and estates of Viscount Lord Lackington.

Serial readers would have been aware of how the title-page vignette refers to the intricacies of the financial plot since those readers had been eagerly purchasing the monthly parts for almost two years. Such readers would have understood why Phiz chose to represent Dunn as a manikin stuffed with straw since "a man of straw" (British idiom) or "straw man" (American idiom) from the period in which Lever wrote the novel meant a duplicitous figure engineering a criminal enterprise. Moreover, since "a man straw" would also have been interpreted as a person who cannot be relied upon to honour his financial commitments, Lever and Phiz could have been using the vignette image to suggest the activities of several characters in the story, including the Honourable Annesley Beecher, Captain Grog Davis, and the Reverend Paul Classon, all of whom are both ethically and financially irresponsible and whose activities verge on outright criminality.

What, then, are we of make of the jubilant response of the scores of ordinary people in the background? The passage "Of the vast numbers who had dealings with him, scarcely any escaped: false title-deeds, counterfeited shares, forged scrip abounded" should suggest anything but unfettered adoration. However, as in the case of the Glengariff land development scheme, the average investor has regarded Dunn's rising from the peasant class to the upper echelons of British society as representing the triumph of the common man. Phiz seems to be suggesting the response of the vast British middle class to Dunn's financial triumphs before his murder and the revellation of his chicanery.

Nevertheless, amidst the crowd of respectable bourgeoisie in top hats three characters in the lower right quadrant stand out: an elderly, balding aristocrat; a well-dressed, middle-aged woman (likely his daughter); and a stocky, somewhat overdressed male figure to their left. Serial readers would likely identify the trio as specific and important figures in the plot strand involving Davenport Dunn. The first, Lord Glengariff, steadfastly refuses to hold Dunn responsible for the loss of his family fortunes, even though the collapse of his real estate development scheme ("The Grand Glengariff Company") has forced him to go into economic exile in Bruges, a broken man tended by the daughter, Lady Augusta, who was to marry Dunn. Simpson (formerly "Simeon") Hankes, Dunn's confidential agent and recipient of a plum civil service post abroad, is likely the second man cheering the Man of Straw. None of this, of course, would the purchaser of the volume edition apprehend until quite late in the narrative.

Related Material: Financial Scandals

- Charles Lever's Swindler as Hero in Davenport Dunn (1858-59)

- The “Stain Cast upon Our Age and Our Civilization:” The Harm Davenport Dunn did to Britain

- Real and Fictional Swindlers: Lever's Davenport Dunn & the Financial Bubble of the Fifties

- John Sadleir

- George Hudson

Other, Less Symbolic Title-page Vignettes by Phiz (1844-1863)

- At the Finger Post in Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (July 1844)

- Rob the Grinder Reading with Captain Cuttle in Dickens's Dombey and Son (April 1848)

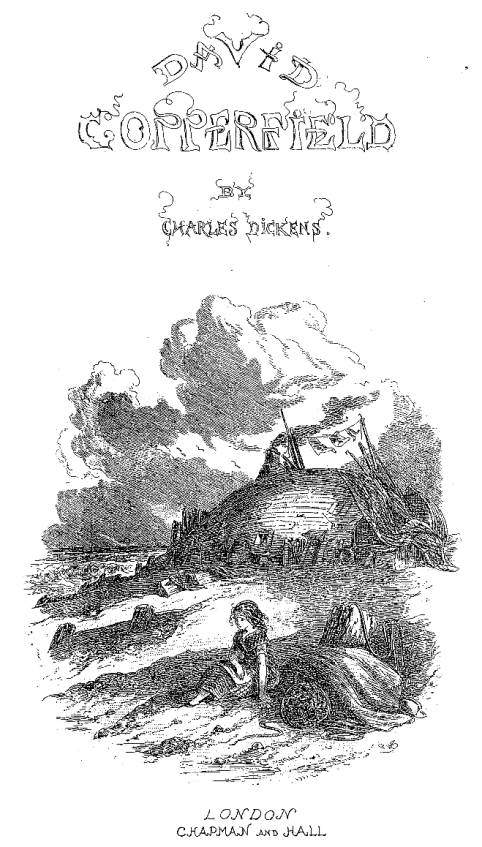

- Little Em'ly at the Houseboat in Dickens's David Copperfield (November 1850)

- Joe the Crossing-sweeper in Dickens's Bleakhouse (1853)

- The Beacon Hill in Ainsworth's The Spendthrift (January 1855)

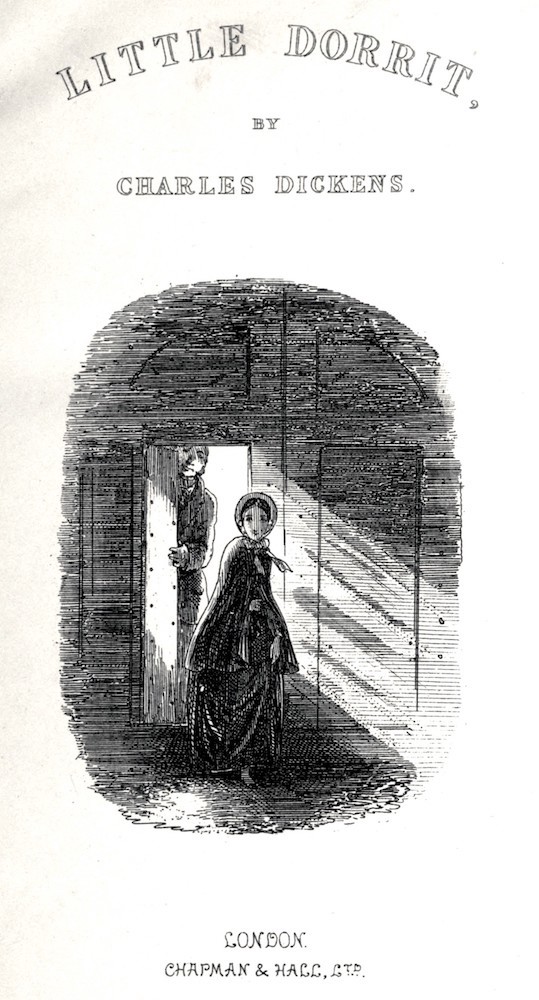

- Amy at the door of the Marshalsea in Dickens's Little Dorrit (June 1857)

- Pursuing the Gipsy on the River in Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe (June 1858)

- In the Bastille in Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (November 1859)

- Polly Dill on Horseback in Lever's Barrington (1863)

References

Browne, John Buchanan. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribner's, 1978.

Fitzpatrick, W. J. The Life of Charles Lever. London: Downey, 1901.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Robb, George. White-Collar Crime in Modern England: Financial Fraud and Financial Fraud and Business Morality, 1845-1929. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2002.

Stevenson, Lionel. Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. New York: Russell & Russell, 1939, rpt. 1969.

Sutherland, John. "Davenport Dunn." The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford U. P., 1989. Page 172.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Phiz

Davenport Dunn

Next

Last modified 12 December 2019