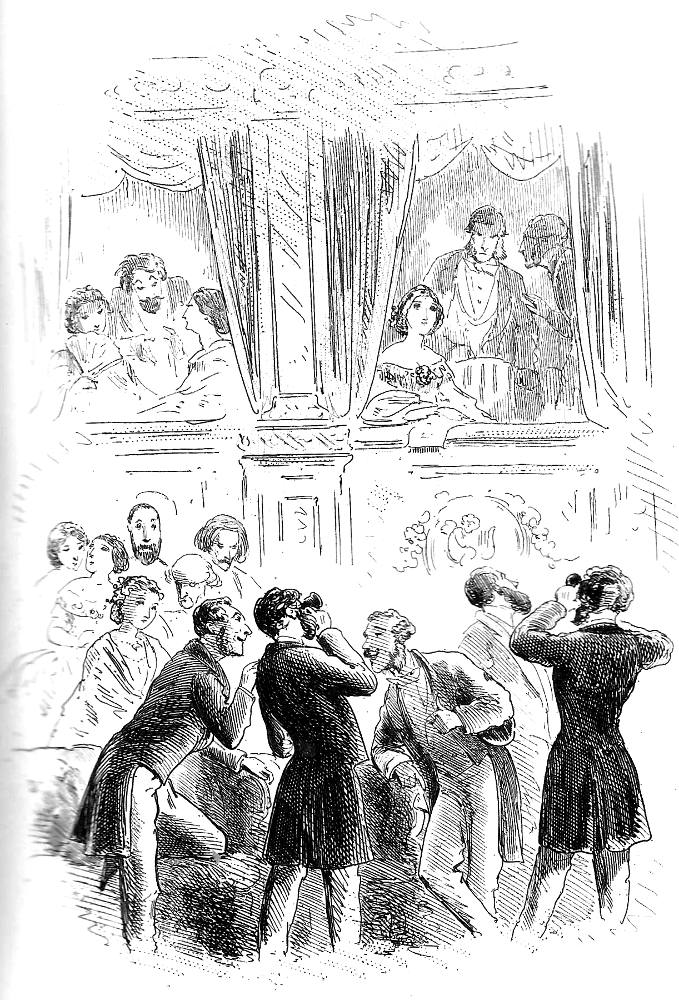

The "Princess" at the Opera

Phiz

Dalziel

February 1858

Steel-engraving

14 cm high by 10 cm wide, vignetted

Fifteenth regular monthly illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day, facing page 251 (1859 edition) in the thirtieth chapter.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image by Simon Cooke; colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliographical Note

This appeared as the fifteenth serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, steel-plate etching; 5 ½ by 4 inches (14 cm high by 10 cm wide), vignetted. The story was serialised by Chapman and Hall in monthly parts, from July 1857 through April 1859. The sixteenth and seventeenth illustrations in the volume initially appeared in reverse order at the very beginning of the eighth monthly instalment, which went on sale on 1 February 1858. This number included Chapters XXVII through XXX, and ran from page 225 through 256.

Passage Illustrated: Annesley Beecher and Grog Davis embarrassed at the Opera

As the piece proceeded, and her interest in the play increased, a slightly heightened colour and an expression of half eagerness gave her beauty all that it had wanted before of animation, and there was now an expression of such captivation on her face that, carried away by that mysterious sentiment which sways masses, sending its secret spell from heart to heart, the whole audience turned from the scene to watch its varying effects upon that beautiful countenance. The opera was Rigoletto, and she continued to translate to her father the touching story of that sad old man, who, lost to every sentiment of honour, still cherished in his heart of hearts his daughter's love. The terrible contrast between his mockery of the world and his affection for his home, the bitter consciousness of how he treated others, conjuring up the terrors of what yet might be his own fate, came to him in her words, as the stage revealed their action, and gradually he leaned over in his eagerness till his head projected outside the box.

“There — wasn't I right about her?” said a voice from one of the stalls beneath. “That's Grog Davis. I know the fellow well.”

“I've won my wager,” said another. “There's old Grog leaning over her shoulder, and there can't be much doubt about her now.”

"Annesley Beecher at one side, and Grog Davis at the other," said a third, make the case very easy reading. "I'll go round and get presented to her."

"Let us leave this, Davis," whispered Beecher, while he trembled from head to foot, — "let us leave this at once. Come down to the crush-room, and I 'll find a carriage."

"Why so — what do you mean?" said Davis; and as suddenly he followed Beecher's glance towards the pit, whence every eye was turned towards them.

That glance was not to be mistaken. It was the steady and insolent stare the world bestows upon those who have neither champions nor defenders; and Davis returned the gaze with a defiance as insulting. [Chapter XXX, "The Opera," 250-51]

Commentary

Lever might have chosen any work from the extensive body of popular Italian opera as the work being performed at the Opera House in Ostend, where Beecher and Davis have gone to retrieve Davis's daughter, "The Princess." However, the novelist has chosen an opera that roused some critical and social furor in the 1850s. Premiered with some triumph at La Fenice, Venice, on 11 March 1851, Verdi's three-act Rigoletto excited a negative, moralistic response because its plot involves a lack of morality. In the Italian libretto was written by Francesco Maria Piave based on the play Le roi s'amuse by Victor Hugo, a serial womanizer seduces a virginal girl. Verdi's tragic story revolves around the licentious Duke of Mantua, his hunch-backed court jester Rigoletto, and Rigoletto's beautiful daughter Gilda. Originally entitled La maledizione (The Curse), the story utilizes a familial curse placed on both the Duke and Rigoletto by a courtier whose daughter the Duke has seduced with Rigoletto's assistance. Lever may be plausibly implying that Grog Davis's much-pampered daughter, for whom he has sacrificed so much, may be tainted by her father's duplicity and corruption now that she has come to live with her after a childhood spent in convent-like institutions.

This is just one of a handful of plates in this volume with such an orientation. Whereas most of the illustrations in this book involve a vertical orientation to capitalise on the height of the page for the width of the plate, here Phiz has chosen a horizontal orientation. The illustrator shows the critical onlookers in the pit, nearest the viewer, and Beecher, Davis, and his daughter in the box, upper right, even though the reader regards the action from the perspective of the trio. In fact, Phiz has employed the horizontal format for only six of the forty-four illustrations in Davenport Dunn (1857-58): The frontispiece, title-page vignette, Calypso's Grotto, The Rev. Paul foraging, A Bottle of Marcobrunner and a Bottle of Smoke, and Mr Hanks in a fix. Contrast this situation with Phiz's choice of orientation in a series such as that for Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44), in which Phiz has employed a vertical orientation (using the height of the page to produce a wide illustration) for none of the forty plates.

In Chapter 30, "The Opera," having taken the train after crossing the Channel, Annesley Beecher arrives at the Hotel Tirlemont, where Davis and his daughter, Lizzy, are staying. Until the waiter announces her presence, Beecher has had no idea that Davis even has a daughter. She has just arrived herself, directly from the Pensionnat Godarde, north-west of Brussels. To celebrate Beecher's arrival, Grog Davis proposes that they take a box forb the Opera that evening, after dinner. The girl knows nothing of her shady father's character or his friend's being a ne'e-do-well bankrupt. At the Opera, Lizzy's appearance in the box excites admiring glances from all sides, and "every opera-glass was turned towards her" (249). Lever has the daughter translate the Italian libretto for her father, giving a synopsis that pointedly draws parallels between the malformed Rigoletto and the sharper, Grog:

The opera was Rigoletto and she continued to translate to her father the touching story of that sad old man, who, lost to every sentiment of honour, still cherished in his heart of hearts his daughter's love. The terrible contrast between his mockery of the world and his affection for his home, the bitter consciousness of how he treated others, conjuring up the terrors of what yet might be his own fate, came to him in her words, as the stage revealed their action, and gradually he leaned over in his eagerness till his head projected outside the box. [250]

The reader now wonders how Grog will prevent his perceptive daughter from learning the truth about her father's dubious business practices and fixing of horse races, and whether the doting parent will be able to forestall a romance between "The Princess" and the dashing Mr. Beecher, the aristocratic but penniless brother of an Anglo-Irish lord.

Bibliography

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: The Man of The Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, February 1858 (Part VIII).

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Phiz

Davenport Dunn

Next

Created 7 March 2019

Last modified 6 July 2020